Rehabilitation

Gait, Amputations, Prostheses, Orthoses, and Neurologic Injury

section 1 Gait

1. Walking is the repetitive process of sequential lower limb motion to move the body from one location to another while maintaining upright stability.

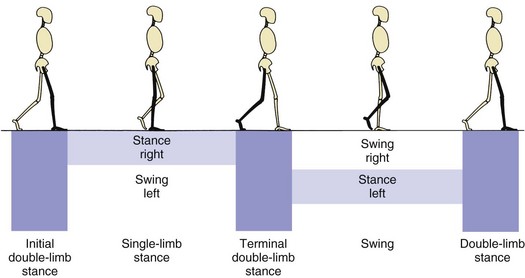

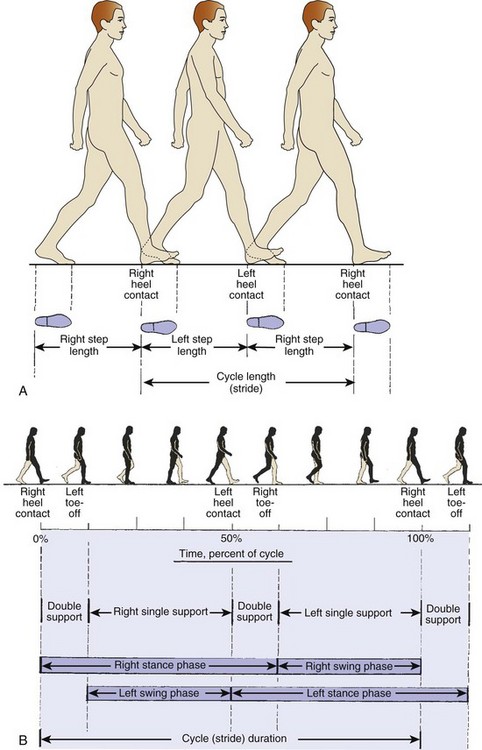

2. Walking is a cyclic, energy-efficient activity: one foot must be in contact with the ground at all times (single-limb support), with a period when both limbs are in contact with the ground (double-limb support) (Figure 10-1).

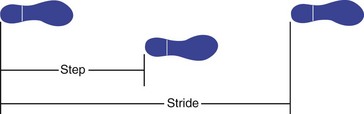

3. The step is the distance between initial swing and initial contact of the same limb.

4. Stride is the period from initial contact to initial contact of the same limb (i.e., each stride comprises two steps) (Figure 10-2).

5. Velocity is a function of cadence (steps per unit of time) and stride length.

6. Running involves a period when neither limb is in contact with the ground.

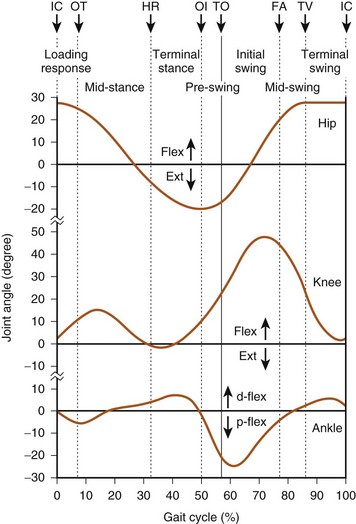

B Phases: Prerequisites for normal gait include stance-phase stability, swing-phase ground clearance, the correct position of the foot before initial contact, and energy-efficient step length and speed.

1. The stance phase occupies 60% of the cycle.

2. The swing phase is 40% of the cycle.

Starts at initial swing (toe-off) and proceeds with limb acceleration to midswing, when the limb decelerates at terminal swing before the next cycle (Figure 10-3)

Starts at initial swing (toe-off) and proceeds with limb acceleration to midswing, when the limb decelerates at terminal swing before the next cycle (Figure 10-3)

During initial swing, the hip and knee flex, and the ankle begins to dorsiflex.

During initial swing, the hip and knee flex, and the ankle begins to dorsiflex.

A The combined phases of gait contribute to an energy-efficient process by lessening excursion of the center of body mass.

B The head, neck, trunk, and arms account for 70% of body weight.

C The trunk center of gravity of body mass is located just anterior to T10, which is 33 cm above the hip joints in an individual of average height (184 cm).

D The body’s line of gravity is anterior to S2 and provides a reference for the moment arm to the center of the joint under consideration. The resulting gait pattern resembles a sinusoidal curve.

III DETERMINANTS OF GAIT (MOTION PATTERNS)

In mechanical terms, there are six independent degrees of freedom (Figure 10-4):

A Pelvic rotation: The pelvis rotates horizontally about a vertical axis, alternately to the left and right of the line of progression, lessening the center-of-mass deviation in the horizontal plane and reducing the impact at initial floor contact.

B Pelvic list: The non–weight-bearing, contralateral side drops 5 degrees, reducing superior deviation.

C Knee flexion at loading: The stance-phase limb is flexed 15 degrees to dampen the impact of initial loading.

D Foot and ankle motion: Through the subtalar joint, damping of the loading response occurs, leading to stability during midstance and efficiency of propulsion at push-off.

E Knee motion: The knee works together with the foot and ankle to decrease necessary limb motion. The knee flexes at initial contact and extends at midstance.

F Lateral pelvic displacement: This relates to the transfer of body weight onto the limb. The length of motion is 5 cm over the weight-bearing limb, narrowing the base of support and increasing stance-phase stability.

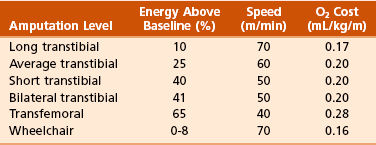

A Agonist and antagonist muscle groups work in concert during the gait cycle to effectively advance the limb through space.

B The hip flexors advance the limb forward during the swing phase and are opposed during terminal swing, before initial contact by the decelerating action of the hip extensors.

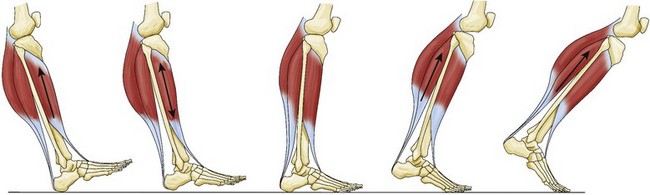

C Most muscle activity is eccentric, which is muscle lengthening while it contracts, and allows an antagonist muscle to dampen the activity of an agonist and act as a “shock absorber” (Figure 10-5).

D Isocentric contraction is muscle length’s remaining constant during contraction (Table 10-1).

E Some muscle activity can be concentric, in which the muscle shortens to move a joint through space.

Abnormal gait patterns are caused by the following factors:

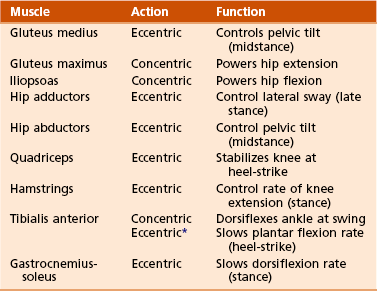

A Muscle weakness or paralysis: decreases the ability to normally move a joint through space. A walking pattern develops on the basis of the specific muscle or muscle group involved and the ability of the individual to acquire a substitution pattern to replace that muscle’s action (Table 10-2).

B Neurologic conditions: may alter gait by producing muscle weakness, loss of balance, reduced coordination between agonist and antagonist muscle groups (i.e., spasticity), and joint contracture.

1. Hip scissoring is associated with overactive adductors, and knee flexion contracture may be caused by hamstring spasticity.

2. Equinus deformity of the foot and ankle may result in a steppage gait and backwards setting of the knee.

C Pain in a limb: creates an antalgic gait pattern, in which the individual shortens the stance phase to lessen the time that the painful limb is loaded. The contralateral swing phase is more rapid.

D Joint abnormalities: alter gait by changing the range of motion of that joint or producing pain

1. A hip and knee with arthritis may have joint contractures and reduced range of motion.

2. An anterior cruciate–deficient knee has quadriceps-avoidance gait, which is a net quadriceps moment during midstance that is lower than normal.

E Hemiplegia: characterized by prolongation of stance and double-limb support

1. Gait impairment may be excessive plantar flexion, weakness, and balance problems.

2. Associated problems are ankle equinus, limitation of knee flexion, and increased hip flexion.

3. Equinus deformity is surgically corrected 1 year after onset.

F Crutches and canes: devices that ameliorate instability and pain, respectively

1. Crutches increase stability by providing two additional loading points.

2. A cane helps shift the center of gravity to the affected side when the cane is used in the opposite hand. This decreases the joint reaction forces of the lower limb and reduces pain.

G Arthritis: Forces across the knee may be four to seven times those of body weight; 70% of the load across the knee occurs through the medial compartment.

H Water walking: There is a significant decrease in joint and total joint contact forces as a result of the effect of buoyancy.

section 2 Amputations

A All or part of a limb may be amputated to treat peripheral vascular disease, trauma, tumor, infection, or a congenital anomaly.

B It is often an alternative to limb salvage and should be considered a reconstructive procedure.

C Because of the psychologic implications and the alteration of body self-image, a multidisciplinary-team approach should be instituted to help the patient.

II METABOLIC COST OF AMPUTEE GAIT

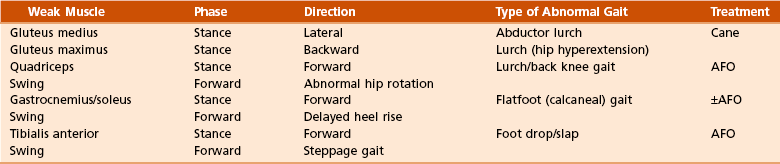

A The metabolic cost of walking is increased with proximal-level amputations and is inversely proportional to the length of the residual limb and the number of functional joints preserved.

B With a proximal amputation, patients have a decreased self-selected, maximum walking speed.

C The higher the level of amputation (or the shorter the stump), the higher the oxygen consumption; thus, the transfemoral amputee with peripheral vascular disease uses close to maximum energy expenditure during normal walking at self-selected velocity (Table 10-3).

D Of note is that the required increase in energy expenditure for ambulation in bilateral transtibial amputation (41%) is less than that of unilateral transfemoral amputation (65%).

A The soft tissue envelope acts as an interface between the bone of the residual limb and the prosthetic socket.

1. Ideally, it is composed of a mobile, securely attached muscle mass covering the bone end and full-thickness skin that tolerates the direct pressures and “pistoning” (mobility) within the prosthetic socket.

2. It is rare for the prosthetic socket to achieve a perfect, intimate fit. A nonadherent soft tissue envelope allows some degree of mobility of the skin and muscle, thus eliminating the shear forces that produce tissue breakdown and ulceration.

B Load transfer (i.e., weight bearing) occurs either directly or indirectly.

1. Direct load transfer (i.e., terminal weight bearing) occurs in knee or ankle disarticulation (Syme amputation). For direct load transfer, intimacy of the prosthetic socket is necessary only for suspension.

2. When the amputation is performed through a long bone (i.e., transfemoral or transtibial), the end of the stump does not take all the weight, and the load is transferred indirectly by the total contact method.

A Nutrition and immune status:

1. Patients with malnutrition or immune deficiency have a high rate of wound failure or infection. A serum albumin level of less than 3.5 g/dL indicates that a patient is malnourished. An absolute lymphocyte count of less than 1500/mm3 is a sign of immune deficiency.

2. If possible, amputation surgery should be delayed in patients with stable gangrene until these values can be improved by nutritional support, usually in the form of oral hyperalimentation.

3. In severely affected patients, nasogastric or percutaneous gastric feeding tubes are sometimes essential.

4. When infection or severe ischemic pain necessitates urgent surgery, open amputation at the most distal, viable level, followed by open-wound management, can be accomplished until wound healing can be optimized.

B Vascular supply: Oxygenated blood is a prerequisite for wound healing, and a hemoglobin concentration of more than 10 g/dL is necessary. Amputation wounds generally heal by collateral flow; thus, arteriography is rarely useful for predicting the success of wound healing.

1. Standard Doppler ultrasonography helps measure arterial pressure and has been used as the measure of vascular inflow to predict the success of wound healing in the ischemic limb.

An absolute Doppler pressure of 70 mm Hg was originally described as the minimum inflow pressure to support wound healing.

An absolute Doppler pressure of 70 mm Hg was originally described as the minimum inflow pressure to support wound healing.

The ischemic index is the ratio of the Doppler pressure at the level being tested to the brachial systolic pressure. It is generally accepted that patients require an ischemic index of 0.5 or greater at the surgical level to support wound healing. The ischemic index at the ankle (i.e., the ankle-brachial index) is the most accepted method for assessing adequate inflow to the ischemic limb.

The ischemic index is the ratio of the Doppler pressure at the level being tested to the brachial systolic pressure. It is generally accepted that patients require an ischemic index of 0.5 or greater at the surgical level to support wound healing. The ischemic index at the ankle (i.e., the ankle-brachial index) is the most accepted method for assessing adequate inflow to the ischemic limb.

In the normal limb, the area under the Doppler waveform tracing is a measure of flow. In at least 15% of patients with diabetes and peripheral vascular disease, those values are falsely elevated and not predictive because of the incompressibility and loss of compliance of calcified peripheral arteries. The ischemic index for toe pressure is more accurate in such patients and, if greater than 0.45, is usually predictive of adequate blood flow.

In the normal limb, the area under the Doppler waveform tracing is a measure of flow. In at least 15% of patients with diabetes and peripheral vascular disease, those values are falsely elevated and not predictive because of the incompressibility and loss of compliance of calcified peripheral arteries. The ischemic index for toe pressure is more accurate in such patients and, if greater than 0.45, is usually predictive of adequate blood flow.

2. Transcutaneous partial pressure of oxygen is the current “gold standard” for measurement of vascular inflow. It reflects the oxygen-delivering capacity of the vascular system to the level of contemplated surgery.

A Pediatric amputations are usually undertaken because of congenital limb deficiencies, trauma, or tumors.

B Congenital amputations are the result of failure of formation.

C The current classification system is based on the original work of the 1975 Conference of the International Society for Prosthetics and Orthotics (ISPO) and the subsequent standard developed by the International Organization for Standardization (ISO).

D Deficiencies are either longitudinal or transverse, with the potential for intercalary deficits.

E Amputation is rarely indicated in congenital upper limb deficiency; even rudimentary appendages can be functionally useful. In the lower limb, amputation of an unstable segment may allow direct load transfer and enhanced walking (e.g., Syme amputation for fibular hemimelia).

F In a growing child, disarticulations should be performed only when it is possible to maintain maximum residual limb length and prevent terminal bony overgrowth.

Such overgrowth usually occurs in the humerus, fibula, tibia, and femur, in that order; it is typical in diaphyseal amputations.

Such overgrowth usually occurs in the humerus, fibula, tibia, and femur, in that order; it is typical in diaphyseal amputations.

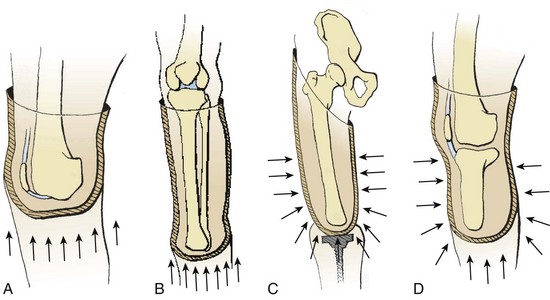

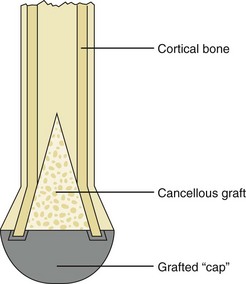

Numerous surgical procedures have been described to resolve this problem, but the best method is surgical revision of the residual limb with adequate resection of bone or autogenous osteochondral stump capping (Figure 10-7).

Numerous surgical procedures have been described to resolve this problem, but the best method is surgical revision of the residual limb with adequate resection of bone or autogenous osteochondral stump capping (Figure 10-7).

1. The absolute indication for amputation after trauma is an ischemic limb with a vascular injury that cannot be repaired.

2. The guidelines for immediate or early amputation of mangled upper limbs differ from those for mangled lower limbs.

3. Early amputation in appropriate scenarios may prevent emotional, marital, financial, and addiction problems.

4. Most grades IIIB and IIIC tibia fractures occur in young men who are laborers and may be more likely to return to gainful employment after amputation and prosthetic fitting.

5. Sensation is not as crucial in the lower limb as in the upper limb, and current prostheses more closely approximate normal function.

6. Disadvantages of limb salvage:

Severe open tibia fractures that are managed by limb salvage rather than amputation are often associated with high rates of mortality and morbidity as a result of infection, increased energy expenditure for ambulation, and decreased potential to return to work.

Severe open tibia fractures that are managed by limb salvage rather than amputation are often associated with high rates of mortality and morbidity as a result of infection, increased energy expenditure for ambulation, and decreased potential to return to work.

Limb salvage for Gustillo-Anderson grades IIIB and IIIC open fractures of the tibia and fibula generally has poor functional outcomes and multiple complications, and multiple surgical procedures may be needed.

Limb salvage for Gustillo-Anderson grades IIIB and IIIC open fractures of the tibia and fibula generally has poor functional outcomes and multiple complications, and multiple surgical procedures may be needed.

The salvaged lower extremity with an insensate plantar weight-bearing surface (loss of posterior tibial nerve), with associated major functional muscle and bone loss, is unlikely to provide a durable limb for stable walking and is a potential source of early or late sepsis.

The salvaged lower extremity with an insensate plantar weight-bearing surface (loss of posterior tibial nerve), with associated major functional muscle and bone loss, is unlikely to provide a durable limb for stable walking and is a potential source of early or late sepsis.

1. In order for patients to learn to walk with a prosthesis and care for their stumps and prostheses, they must possess certain cognitive capacities: memory, attention, concentration, and organization.

1. A majority of patients who undergo amputation are diabetic, with inherent immune deficiency.

2. The most important risk factors in amputation in diabetic patients are the presence of peripheral neuropathy and development of deformity and infection.

1. Most of the other patients who undergo amputation are malnourished patients with peripheral vascular disease of sufficient magnitude to necessitate amputation, and their coronary and cerebral arteries are diseased.

2. Appropriate consultation with physical therapy, social work, and psychology departments is important to determine rehabilitation potential.

3. Medical consultation helps determine cardiopulmonary reserve. The vascular surgeon should determine whether vascular reconstruction is feasible or appropriate.

4. The biologic amputation level is the most distal functional amputation level with a high probability of supporting wound healing.

This level is determined by the presence of adequate, viable local tissue to construct a residual limb capable of supporting weight bearing; an adequate vascular inflow; and serum albumin level and a total lymphocyte count sufficient to aid surgical wound healing.

This level is determined by the presence of adequate, viable local tissue to construct a residual limb capable of supporting weight bearing; an adequate vascular inflow; and serum albumin level and a total lymphocyte count sufficient to aid surgical wound healing.

The selection of an appropriate amputation level is determined by combining the biologic amputation level with the rehabilitation potential in order to choose the level that maximizes ultimate functional independence.

The selection of an appropriate amputation level is determined by combining the biologic amputation level with the rehabilitation potential in order to choose the level that maximizes ultimate functional independence.

5. Morbidity and mortality rates have remained unchanged for several decades. Thirty percent of patients with peripheral vascular disease die in the first 3 months after amputation, and nearly 50% die within the first year. The overall rate of prosthetic use is 43%.

A Goal of surgery: to remove the tumor with adequate surgical margins.

B Amputation versus limb salvage:

1. Advances in chemotherapy and allograft or prosthetic reconstruction have made limb salvage a viable option in extremity sarcomas.

2. If adequate margins can be achieved with limb salvage, the decision can then be based on expected functional outcome.

3. The advantage of limb salvage over amputation—with regard to energy expenditure to ambulate, quality-of-life measures, and function with activities of daily living—is controversial in the literature.

4. Expected functional outcome should include the psychosocial and body-image values associated with limb salvage.

A Skin flaps should be of full thickness, and dissection between tissue planes should be avoided.

B Periosteal stripping should be sufficient to allow for bone transection; this minimizes regenerative bone overgrowth.

C Wounds should not be sutured under tension. Muscles are best secured directly to bone at resting tension (myodesis) rather than to antagonist muscle (myoplasty).

D Stable residual limb muscle mass can improve function by reducing atrophy and providing a stable soft tissue envelope over the end of the bone.

E All transected nerves form neuromata. The nerve end should come to lie deep in a soft tissue envelope, away from potential pressure areas. Crushing the nerve may contribute to postoperative phantom or limb pain.

F Rigid dressings (postoperative) help reduce swelling, decrease pain, and protect the stump from trauma.

G Early prosthetic fitting is done within 5 to 21 days after surgery in selected patients.

1. Phantom limb sensation—the feeling that all or part of the amputated limb is present—occurs in almost all adults who have undergone amputation. It usually decreases with time.

2. Phantom pain is a burning, painful sensation in the part having undergone amputation. It is diminished by prosthetic use, physical therapy, compression, and transcutaneous nerve stimulation.

3. A common cause of residual pain is complex regional pain syndrome (reflex sympathetic dystrophy) or causalgia. Amputation should not be performed for this condition.

4. Localized stump pain is often related to bony or soft tissue problems.

5. Pain referred to the limb occurs in a frequent number of cases.

1. Postoperative edema occurs after amputation. It may impede wound healing and place significant tension on the tissues.

2. Rigid dressings and soft compression help reduce the problem.

3. Swelling occurring after stump maturation is usually caused by poor socket fit, medical problems, or trauma.

4. Persistence of chronic swelling may lead to verrucous hyperplasia, a wartlike overgrowth of skin with pigmentation and serous discharge.

XI UPPER LIMB AMPUTATIONS (Figure 10-8)

Wrist disarticulation has two advantages over transradial amputation:

Wrist disarticulation has two advantages over transradial amputation:

Preservation of more forearm rotation because of preservation of the distal radioulnar joint

Preservation of more forearm rotation because of preservation of the distal radioulnar joint

Improved prosthetic suspension because of the flare of the distal radius

Improved prosthetic suspension because of the flare of the distal radius

Effective function can be obtained at this level of amputation. Forearm rotation and strength are directly related to the length of the transradial (below-elbow) residual limb.

Effective function can be obtained at this level of amputation. Forearm rotation and strength are directly related to the length of the transradial (below-elbow) residual limb.

B Transradial amputation or elbow disarticulation

1. Complete brachial plexus injury and a nonfunctioning hand and forearm may be best treated by a transradial amputation or elbow disarticulation, which can be fitted with a prosthesis.

2. The optimal length of the residual limb is at the junction of the middle and distal thirds of the forearm, where the soft tissue envelope can be repaired by myodesis and the components of a myoelectric prosthesis can be hidden within the prosthetic shank.

3. Because the patient can maintain function at this level prosthetically only by being able to open and close the terminal device, retention of the elbow joint is essential.

4. The length and shape of elbow disarticulation provides improved suspension and lever-arm capacity.

5. To enhance suspension and reduce the need for shoulder harnessing, a 45- to 60-degree distal humeral osteotomy is performed.

6. Gangrene of the upper limb, when it is not due to Raynaud or Buerger disease, represents end-stage disease, especially in diabetic patients. Such patients usually do not survive beyond 24 months.

XII LOWER LIMB AMPUTATIONS (see Figure 10-8)

1. Patients with ischemia generally ambulate with a propulsive gait pattern, so they suffer little disability from toe amputation.

2. Patients with traumatic amputions lose some stability after toe amputation in the late-stance phase.

3. The great toe should be amputated distal to the insertion of the flexor hallucis brevis.

4. Isolated second-toe amputation should be performed just distal to the proximal phalanx metaphyseal flare, leaving the stump to act as a buttress and prevent late hallux valgus.

5. Patients who undergo single outer (first or fifth) ray resections function well in standard shoes.

6. Resection of more than one ray leaves the forefoot narrow, which is difficult to fit in shoes, and often results in a late equinus deformity.

7. Central ray resections are complicated by prolonged wound healing and rarely achieve better results than does midfoot amputation.

B Transmetatarsal and Lisfranc tarsal-metatarsal amputation

1. There is little functional difference in the outcomes of these two procedures. The long plantar flap acts as a myocutaneous flap and is preferred to fish-mouth dorsal-plantar flaps.

2. Transmetatarsal amputation should be performed through the proximal metaphyses to prevent late plantar pressure ulcers under the residual bone ends.

3. Percutaneous Achilles tendon lengthening should be performed with transmetatarsal and Lisfranc amputations to prevent the late development of equinus or equinovarus deformity.

4. Late varus deformity can be corrected with the transfer of the tibialis anterior tendon to the neck of the talus.

The second tarsometarsal joint should be osteotomized in order to preserve midfoot stability.

The second tarsometarsal joint should be osteotomized in order to preserve midfoot stability.

The soft tissue at the fifth metatarsal base should be preserved because this represents the insertion site of peroneus brevis and tertius, which act as antagonists to the posterior tibial tendon.

The soft tissue at the fifth metatarsal base should be preserved because this represents the insertion site of peroneus brevis and tertius, which act as antagonists to the posterior tibial tendon.

5. Some authors have reported reasonable functional outcomes with hindfoot amputation (i.e., Chopart or Boyd amputations), but most experts recommend avoiding amputation at these levels if possible in patients with diabetes or vascular disease.

6. Although children have been reported to function reasonably well, adults retain an inadequate lever arm and are prone to experience fixed equinus deformity of the heel if Achilles tendon lengthening and tibialis anterior tendon transfer are not performed.

C Ankle disarticulation (Syme amputation)

1. Often performed for forefoot trauma, this amputation allows direct load transfer and is rarely complicated by late residual limb ulcers or tissue breakdown.

2. It provides a stable gait pattern that rarely necessitates prosthetic gait training after surgery.

3. The outcome is more energy efficient than that of a midfoot amputation, despite the fact that it is a more proximal level.

4. Surgery should be performed in one stage, even in ischemic limbs with insensate heel pads.

5. The posterior tibial artery must be patent to ensure healing.

6. The malleoli and metaphyseal flares should be removed from the tibia and fibula, but the remaining tibial articular surface should be retained to provide a resilient residual limb.

7. The heel pad should be secured to the tibia either anteriorly through drill holes or posteriorly by securing the Achilles tendon.

D Transtibial (below-knee) amputation

1. A long posterior myocutaneous flap is the preferred method of creating a soft tissue envelope, especially in patients with vascular disease, inasmuch as the direction of blood flow is from posterior to anterior.

2. The optimum bone length is at least 12 cm below the knee joint or longer if adequate amounts of the gastrocnemius or soleus muscle can be used to construct a durable soft tissue envelope.

3. The posterior muscle should be secured to the beveled anterior tibia by myodesis.

4. Rigid dressings are preferred during the early postoperative period, and early prosthetic fitting may be started 5 to 21 days after surgery if the residual limb is capable of transferring load and if the patient has a satisfactory physical reserve.

E Knee disarticulation (through-knee amputation)

1. The current technique involves the use of a long posterior flap, with the gastrocnemius muscle as end padding.

The alternative is to use sagittal skin flaps and cover the end of the femur with the gastrocnemius muscle to act as a soft tissue envelope end pad.

The alternative is to use sagittal skin flaps and cover the end of the femur with the gastrocnemius muscle to act as a soft tissue envelope end pad.

2. The patella tendon is sutured to the cruciate ligaments in the notch, leaving the patella on the anterior femur.

This level is generally used in nonambulatory patients who can support wound healing at the transtibial or distal level.

This level is generally used in nonambulatory patients who can support wound healing at the transtibial or distal level.

Data from the Lower Extremity Assessment Project (LEAP) study have demonstrated this amputation to result in the slowest walking speed and produce the least self-reported satisfaction.

Data from the Lower Extremity Assessment Project (LEAP) study have demonstrated this amputation to result in the slowest walking speed and produce the least self-reported satisfaction.

3. Knee disarticulation is muscle balanced and provides an excellent weight-bearing platform for sitting and a lever arm for bed to chair transfer. When this amputation is performed in a potential walker, it provides a residual limb for direct bed to chair transfer (end bearing).

F Transfemoral (above-knee) amputation

1. This amputation increases the energy cost for walking.

2. Patients with transfemoral amputations who have peripheral vascular disease are unlikely to become efficient walkers; thus, salvaging the limb at the knee disarticulation (transtibial level) is crucial for maintaining functional walking independence.

3. With greater femoral length, the lever arm, suspension, and limb advancement are optimized. The optimum transfemoral bone length is 12 cm above the knee joint to accommodate the prosthetic knee.

4. Adductor myodesis is important for maintaining femoral adduction during the stance phase in order to allow optimal prosthetic function (Figure 10-9).

5. The major deforming force is toward abduction and flexion. Adductor myodesis at normal muscle tension eliminates the problem of adductor roll in the groin. Transecting the adductor magnus results in a loss of 70% of the adductor pull (Figure 10-10).

6. Rigid dressings are difficult to apply and maintain at this level. Elastic compression dressings are used and may be suspended about the opposite iliac crest.

1. This procedure is infrequently performed, and of the patients who undergo this amputation, only a few make meaningful use of prostheses because of the high energy requirements for walking.

2. Patients who have suffered trauma or who have tumors occasionally use the prosthesis for limited activity. These patients sit in their prostheses and must use the torso in order to achieve momentum for “throwing” the limb forward to advance it.

section 3 Prostheses

1. The shoulder provides the center of the radius of the functional sphere of the upper limb. The elbow acts as the caliper to position the hand at a workable distance from that center in order to perform its tasks.

2. In a normal arm, tasks performed with the use of multiple joint segments usually occur simultaneously, whereas upper limb prostheses perform these same tasks sequentially; thus, joint- and residual-limb-length salvage is directly correlated with functional outcome.

3. Motion at the retained joints is essential for maximizing that function.

4. Residual limb length is important for suspending the prosthetic socket and providing the lever arm necessary to “drive” the prosthesis through space.

C Timing of prosthetic fitting

1. Prosthetic fitting should be undertaken as soon as possible after amputation, even before complete wound healing has occurred.

2. For transradial amputation, the outcomes for prosthetic limb use vary from 70% to 85% when prosthetic fitting occurs within 30 days of amputation, in contrast to less than 30% when the fitting starts later.

D Types of prostheses for different levels of amputation

1. Midlength transradial amputation:

Myoelectric prostheses provide good cosmesis and are used for sedentary work. They can be used in any position, including overhead activity, and are the most successful for patients with midlength transradial amputations, for whom only the terminal device needs to be activated.

Myoelectric prostheses provide good cosmesis and are used for sedentary work. They can be used in any position, including overhead activity, and are the most successful for patients with midlength transradial amputations, for whom only the terminal device needs to be activated.

Body-powered prostheses are used for heavy labor. The terminal device is activated by shoulder flexion and abduction. For optimal mechanical efficiency of figure-8 harnesses, the harness ring must be at the spinous process of C7 and slightly to the nonamputated side.

Body-powered prostheses are used for heavy labor. The terminal device is activated by shoulder flexion and abduction. For optimal mechanical efficiency of figure-8 harnesses, the harness ring must be at the spinous process of C7 and slightly to the nonamputated side.

2. Elbow disarticulation and transhumeral (above-elbow) amputations

When the residual forearm is so short that it precludes an adequate lever arm for driving the prosthesis through space, supracondylar suspension (Munster socket) and step-up hinges can be used to augment function.

When the residual forearm is so short that it precludes an adequate lever arm for driving the prosthesis through space, supracondylar suspension (Munster socket) and step-up hinges can be used to augment function.

In elbow disarticulation and transhumeral (above-elbow) amputations, two motions are needed to develop prehension; thus, these levels of amputation have significantly less efficient outcomes, and the prostheses are heavier than they are for amputation at the transradial level.

In elbow disarticulation and transhumeral (above-elbow) amputations, two motions are needed to develop prehension; thus, these levels of amputation have significantly less efficient outcomes, and the prostheses are heavier than they are for amputation at the transradial level.

Elbow flexion and extension are controlled by shoulder extension and depression. Amputations at these levels provide minimal function because the patient must sequentially control two joints and a terminal device.

Elbow flexion and extension are controlled by shoulder extension and depression. Amputations at these levels provide minimal function because the patient must sequentially control two joints and a terminal device.

The best function with the least weight at the lowest cost is provided by hybrid prosthetic systems in which myoelectric, traditional body-powered, and body-driven switch components are combined.

The best function with the least weight at the lowest cost is provided by hybrid prosthetic systems in which myoelectric, traditional body-powered, and body-driven switch components are combined.

3. Proximal transhumeral and shoulder disarticulation amputations

A Prosthetic feet: Several designs are available and divided into five classes.

The single-axis foot is based on an ankle hinge that provides dorsiflexion and plantar flexion.

The single-axis foot is based on an ankle hinge that provides dorsiflexion and plantar flexion.

The disadvantages of the single-axis foot include poor durability and cosmesis.

The disadvantages of the single-axis foot include poor durability and cosmesis.

2. Solid-ankle, cushioned-heel (SACH) foot

This has been the standard for decades and was appropriate for general use in patients with low levels of activity.

This has been the standard for decades and was appropriate for general use in patients with low levels of activity.

It may lead to overload problems on the nonamputated foot, and its use is being discontinued.

It may lead to overload problems on the nonamputated foot, and its use is being discontinued.

The selection of the correct dynamic prosthetic foot depends on the patient’s height, weight, activity level, access for maintenance, cosmesis, and funding.

The selection of the correct dynamic prosthetic foot depends on the patient’s height, weight, activity level, access for maintenance, cosmesis, and funding.

The dynamic-response foot prostheses, including the Seattle foot, Carbon Copy II/III, and Flex Foot, allow amputees to undertake most normal activities (Figure 10-11).

The dynamic-response foot prostheses, including the Seattle foot, Carbon Copy II/III, and Flex Foot, allow amputees to undertake most normal activities (Figure 10-11).

Dynamic-response foot prostheses may be grouped into articulated and nonarticulated.

Dynamic-response foot prostheses may be grouped into articulated and nonarticulated.

Articulated dynamic-response foot

Articulated dynamic-response foot

These allow inversion/eversion and rotation of the foot and are useful for activities on uneven surfaces.

These allow inversion/eversion and rotation of the foot and are useful for activities on uneven surfaces.

They may absorb loads and decrease shear forces to the residual limb.

They may absorb loads and decrease shear forces to the residual limb.

Most dynamic-response feet have a flexible keel and are the standard for general use (Figure 10-12). The keel deforms under load, becoming a spring and allowing dorsiflexion and thereby decreasing the loading on the normal side and providing a springlike response for push-off.

Most dynamic-response feet have a flexible keel and are the standard for general use (Figure 10-12). The keel deforms under load, becoming a spring and allowing dorsiflexion and thereby decreasing the loading on the normal side and providing a springlike response for push-off.

Figure 10-12 Ceterus prosthetic foot with leaf spring and shock absorber. (Courtesy of Ossur Americas, Aliso Viejo, California.)

Posterior projection of the keel provides a response at heel-strike for smooth transition through the stance phase. A sagittal split allows for moderate inversion or eversion.

Posterior projection of the keel provides a response at heel-strike for smooth transition through the stance phase. A sagittal split allows for moderate inversion or eversion.

1. These shanks provide the structural link between or among prosthetic components.

2. Two varieties exist: endoskeletal, with a soft exterior and load-bearing tubing inside (the most common), and exoskeletal, with a hard load-bearing exterior shell.

3. Rotator units are sometimes added for patients involved in twisting activities (e.g., golf) or for sitting.

C Prosthetic knees (Table 10-4)

1. Prosthetic knees provide controlled knee motion in the prosthesis.

2. These components are used in transfemoral and knee disarticulation and are chosen on the basis of the patient’s needs.

3. Alignment stability (the position of the prosthetic knee in relation to the patient’s line of weight bearing) is important in the design and fitting of prosthetic knees. Placing the knee center of rotation posterior to the line of weight bearing allows control in the stance phase but makes flexion difficult. Alternatively, with the knee center of rotation anterior to the line of weight bearing, flexion is made easier but at the expense of control.

4. Only the polycentric knee component offers the possibility of both options by having a variable center of rotation. Six basic types of knees are available:

Polycentric (four-bar linkage) knee: This prosthesis has a moving instant center of rotation that provides for different stability characteristics during the gait cycle and may allow increased flexion for sitting. It is recommended for patients with transfemoral amputations, those with knee disarticulations, and those with bilateral amputations (Figure 10-13).

Polycentric (four-bar linkage) knee: This prosthesis has a moving instant center of rotation that provides for different stability characteristics during the gait cycle and may allow increased flexion for sitting. It is recommended for patients with transfemoral amputations, those with knee disarticulations, and those with bilateral amputations (Figure 10-13).

Stance-phase control (weight-activated [safety]) knee: This knee functions like a constant-friction knee during the swing phase but “freezes” by application of high-friction housing when weight is applied to the limb. Its use is reserved primarily for older patients, those with very proximal amputations, or those walking on uneven terrain.

Stance-phase control (weight-activated [safety]) knee: This knee functions like a constant-friction knee during the swing phase but “freezes” by application of high-friction housing when weight is applied to the limb. Its use is reserved primarily for older patients, those with very proximal amputations, or those walking on uneven terrain.

Fluid-control (hydraulic and pneumatic) knee: This knee allows adjustment of cadence response by changing resistance to knee flexion by means of a piston mechanism. The design prevents excessive flexion and is extended earlier in the gait cycle, allowing a more fluid gait. The knee is best used in active patients who prefer greater utility and variability at the expense of more weight.

Fluid-control (hydraulic and pneumatic) knee: This knee allows adjustment of cadence response by changing resistance to knee flexion by means of a piston mechanism. The design prevents excessive flexion and is extended earlier in the gait cycle, allowing a more fluid gait. The knee is best used in active patients who prefer greater utility and variability at the expense of more weight.

Constant-friction knee: This knee prosthesis is essentially a hinge that is designed to dampen knee swing by a screw or rubber pad that applies friction to the knee bolt. It is designed for general utility and may be used on uneven terrain. It is the most common knee prosthesis for children. Its major disadvantages are that it allows only single-speed walking and relies solely on alignment for stance-phase stability; therefore, it is not recommended for older, weaker patients.

Constant-friction knee: This knee prosthesis is essentially a hinge that is designed to dampen knee swing by a screw or rubber pad that applies friction to the knee bolt. It is designed for general utility and may be used on uneven terrain. It is the most common knee prosthesis for children. Its major disadvantages are that it allows only single-speed walking and relies solely on alignment for stance-phase stability; therefore, it is not recommended for older, weaker patients.

Variable-friction (cadence control) knee: This device allows resistance to knee flexion to increase as the knee extends by employing a number of staggered friction pads. This knee allows walking at different speeds but is neither durable nor available in endoskeletal systems.

Variable-friction (cadence control) knee: This device allows resistance to knee flexion to increase as the knee extends by employing a number of staggered friction pads. This knee allows walking at different speeds but is neither durable nor available in endoskeletal systems.

Manual locking knee: This knee consists of a constant-friction knee hinge with a positive lock in extension that can be unlocked to allow functioning similar to that of a constant-friction knee. The knee is often left locked in extension for more stability. It has limited indications and is used primarily in weak, unstable patients; those just learning to use prostheses; and blind amputees.

Manual locking knee: This knee consists of a constant-friction knee hinge with a positive lock in extension that can be unlocked to allow functioning similar to that of a constant-friction knee. The knee is often left locked in extension for more stability. It has limited indications and is used primarily in weak, unstable patients; those just learning to use prostheses; and blind amputees.

1. Sockets are prosthetic components designed to provide comfortable functional control and even pressure distribution on the amputated stump. Sockets can be hard (rigid or unlined) or soft (lined with a resilient material and/or flexible shell). In general, the suction-and-socket contour is the primary suspension modality used. The suction socket provides an airtight seal by means of a pressure differential between the socket and atmosphere. Total-contact support of the residual limb surface prevents edema formation. In total-contact support, different areas have different loads.

Transfemoral, or quadrilateral, sockets, in which the posterior brim provides a shelf for the ischial tuberosity, have been the classic suspension system. However, the design made it difficult to keep the femur in adduction. Narrow mediolateral (ischial containment) transfemoral sockets distribute the proximal and medial concentrations of forces more evenly, as well as enhance rotational control of the socket (Figure 10-14). The ischium and ramus are contained within the socket of these more anatomic, comfortable, and functional designs. Socket design for transfemoral prostheses allows for 10 degrees of adduction of the femur (to stretch the gluteus medius, allowing adequate strength for midstance stability) and 5 degrees of flexion (to stretch the gluteus maximus, allowing greater hip extension).

Transfemoral, or quadrilateral, sockets, in which the posterior brim provides a shelf for the ischial tuberosity, have been the classic suspension system. However, the design made it difficult to keep the femur in adduction. Narrow mediolateral (ischial containment) transfemoral sockets distribute the proximal and medial concentrations of forces more evenly, as well as enhance rotational control of the socket (Figure 10-14). The ischium and ramus are contained within the socket of these more anatomic, comfortable, and functional designs. Socket design for transfemoral prostheses allows for 10 degrees of adduction of the femur (to stretch the gluteus medius, allowing adequate strength for midstance stability) and 5 degrees of flexion (to stretch the gluteus maximus, allowing greater hip extension).

Transtibial sockets: Weight bearing by the patella tendon loads all areas of the residual limb that tolerate weight (i.e., patella tendon, medial tibial flare, anterior compartment, gastrocnemius muscle, and fibular shaft). Weight-intolerant areas include the tibial crest and tubercle, distal fibula and fibular head, peroneal nerve, and hamstring tendons. The patella tendon–bearing supracondylar/suprapatellar socket has proximal extensions over the distal femoral condyles and patella. Total-surface weight bearing is different from total-contact weight bearing. With total-surface weight bearing, pressure is distributed more equally across the entire surface of the transtibial residual limb, and the interface liner material in the socket is important. Urethane liners cope with multidirectional forces by easy material distortion and recovery to the original shape. Another liner is made of mineral oil gel with reinforcing fabric. These liners provide good shock absorption and reduce skin problems. The anterior wedge shape of the socket helps control rotation of the socket on the limb.

Transtibial sockets: Weight bearing by the patella tendon loads all areas of the residual limb that tolerate weight (i.e., patella tendon, medial tibial flare, anterior compartment, gastrocnemius muscle, and fibular shaft). Weight-intolerant areas include the tibial crest and tubercle, distal fibula and fibular head, peroneal nerve, and hamstring tendons. The patella tendon–bearing supracondylar/suprapatellar socket has proximal extensions over the distal femoral condyles and patella. Total-surface weight bearing is different from total-contact weight bearing. With total-surface weight bearing, pressure is distributed more equally across the entire surface of the transtibial residual limb, and the interface liner material in the socket is important. Urethane liners cope with multidirectional forces by easy material distortion and recovery to the original shape. Another liner is made of mineral oil gel with reinforcing fabric. These liners provide good shock absorption and reduce skin problems. The anterior wedge shape of the socket helps control rotation of the socket on the limb.

A supracondylar suspension system is recommended when the residual limb is less than 5 cm long. The socket is designed to increase the surface area for pressure distribution by raising the medial and lateral socket brim. A wedge may be used in the soft liner.

A supracondylar suspension system is recommended when the residual limb is less than 5 cm long. The socket is designed to increase the surface area for pressure distribution by raising the medial and lateral socket brim. A wedge may be used in the soft liner.

A supracondylar-suprapatellar suspension system encloses the patella in the socket and has a bar proximal to the patella. This design also provides mediolateral stability, and no additional cuffs or straps are required. Corset-type prostheses can lead to verrucous hyperplasia and thigh atrophy, but they reduce socket loads, control the direction of swing, and provide some additional weight support.

A supracondylar-suprapatellar suspension system encloses the patella in the socket and has a bar proximal to the patella. This design also provides mediolateral stability, and no additional cuffs or straps are required. Corset-type prostheses can lead to verrucous hyperplasia and thigh atrophy, but they reduce socket loads, control the direction of swing, and provide some additional weight support.

2. In prosthetic sleeves, friction and negative pressure are used for suspension. The sleeves fit snugly to the upper third of the tibial prosthesis and are made from neoprene, latex, silicone, or thermoplastic elastomers.

Gel-liner suspension systems with a locking pin constitute the preferred method of suspension.

Gel-liner suspension systems with a locking pin constitute the preferred method of suspension.

Liners are made from silicone, urethane, or thermoplastic elastomer.

Liners are made from silicone, urethane, or thermoplastic elastomer.

The sleeve rolls onto the stump, and the locking pin is then locked into the socket (Figure 10-15).

The sleeve rolls onto the stump, and the locking pin is then locked into the socket (Figure 10-15).

Figure 10-15 A, Gel liner suspension with locking pin. B, Transtibial prosthesis with liner locked in place.

The liners provide suspension through suction and friction and act as the socket interface.

The liners provide suspension through suction and friction and act as the socket interface.

Prosthetic socks worn over the liner accommodate volume fluctuation.

Prosthetic socks worn over the liner accommodate volume fluctuation.

This suspension allows unrestricted knee flexion and minimal piston action.

This suspension allows unrestricted knee flexion and minimal piston action.

Vacuum (suction) suspension is frequently used.

Vacuum (suction) suspension is frequently used.

It relies on surface tension, negative pressure, and muscle contraction.

It relies on surface tension, negative pressure, and muscle contraction.

A one-way expulsion valve helps maintain negative pressure, and no belts or straps are required. Stable body weight is required for this intimate fit.

A one-way expulsion valve helps maintain negative pressure, and no belts or straps are required. Stable body weight is required for this intimate fit.

Roll-on silicone or thermoplastic liners may be used with or without locking pins.

Roll-on silicone or thermoplastic liners may be used with or without locking pins.

The total-elastic suspension belt, which is made of neoprene, fastens around the waist and spreads over a larger surface area (Figure 10-16). It is an excellent auxiliary suspension.

The total-elastic suspension belt, which is made of neoprene, fastens around the waist and spreads over a larger surface area (Figure 10-16). It is an excellent auxiliary suspension.

Silesian belts are used to prevent socket rotation in limbs with redundant tissue. Such belts also prevent the socket from slipping off when suction sockets are fitted to short transfemoral stumps and the patient sits.

Silesian belts are used to prevent socket rotation in limbs with redundant tissue. Such belts also prevent the socket from slipping off when suction sockets are fitted to short transfemoral stumps and the patient sits.

E Common prosthetic problems (Table 10-5)

Table 10-5![]()

Prosthetic Foot Gait Abnormalities

| Foot Position | Gait Abnormality |

| Inset | Varus strain, pain (proximomedial, distolateral), circumduction |

| Outset | Valgus strain, pain (proximolateral, distomedial), broad-based gait |

| Forward placement | Increased knee extension (patellar pain) but stable |

| Posterior placement | Increased knee flexion/instability |

| Dorsiflexed foot | Increased patellar pressure |

| Plantar-flexed foot | Drop-off, patellar pressure |

Pistoning during the swing phase of gait is usually caused by an ineffective suspension system.

Pistoning during the swing phase of gait is usually caused by an ineffective suspension system.

Pistoning in the stance phase results from a poor socket fit or volume changes in the stump (a change in thickness of the stump sock may be needed).

Pistoning in the stance phase results from a poor socket fit or volume changes in the stump (a change in thickness of the stump sock may be needed).

Alignment problems are common (see Table 10-5).

Alignment problems are common (see Table 10-5).

Pressure-related pain or redness should be corrected, with relief of the prosthesis in the affected area.

Pressure-related pain or redness should be corrected, with relief of the prosthesis in the affected area.

Other problems may be related to the foot: Too soft a heel results in excessive knee extension, whereas too hard a heel causes knee flexion and lateral rotation of the toes.

Other problems may be related to the foot: Too soft a heel results in excessive knee extension, whereas too hard a heel causes knee flexion and lateral rotation of the toes.

Excessive prosthetic length and weak hip abductors or flexors can lead to circumduction, vaulting, and lateral trunk bending.

Excessive prosthetic length and weak hip abductors or flexors can lead to circumduction, vaulting, and lateral trunk bending.

Hip flexion contractures and insufficient anterior socket support can lead to excessive lumbar lordosis (compensatory).

Hip flexion contractures and insufficient anterior socket support can lead to excessive lumbar lordosis (compensatory).

Inadequate prosthetic knee flexion can lead to a terminal knee snap.

Inadequate prosthetic knee flexion can lead to a terminal knee snap.

A medial whip (heel-in, heel-out) can be caused by a varus knee, excessive external rotation of the knee axis, or muscle weakness.

A medial whip (heel-in, heel-out) can be caused by a varus knee, excessive external rotation of the knee axis, or muscle weakness.

A lateral whip (heel-out, heel-in) is caused by the opposite problem: valgus knee, internal rotation at knee, or muscle weakness. Table 10-6 summarizes common transfemoral prosthetic gait problems.

A lateral whip (heel-out, heel-in) is caused by the opposite problem: valgus knee, internal rotation at knee, or muscle weakness. Table 10-6 summarizes common transfemoral prosthetic gait problems.

Table 10-6![]()

Transfemoral Prosthetic Gait Abnormalities

| Gait Abnormality | Prosthetic Problem |

| Lateral trunk bending | Short prosthesis, weak abductors, poor fit |

| Abducted gait | Poor socket fit medially |

| Circumducted gait | Prosthesis too long, excess knee friction |

| Vaulted gait | Prosthesis too long, poor suspension |

| Foot rotation at heel-strike | Heel too stiff, loose socket |

| Short stance phase | Painful stump, knee too loose |

| Knee instability | Knee too anterior, foot too stiff |

| Mediolateral whip | Excessive knee rotation, tight socket |

| Terminal snap | Quadriceps weakness, unsure patient |

| Foot slap, knee hyperextension | Heel too soft |

| Knee flexion | Heel too hard |

| Excessive lordosis | Hip flexion contracture, socket problems |

section 4 Orthoses

A The primary function of an orthosis is control of the motion of certain body segments.

B Orthoses are used to protect long bones or unstable joints, support flexible deformities, and occasionally substitute for a functional task. They may be static, dynamic, or a combination of these.

C With few exceptions, orthoses are not indicated for correction of fixed deformities or for spastic deformities that cannot be easily controlled manually.

D Orthoses are named according to the joints they control and the method used to obtain/maintain that control (e.g., a short leg, below-the-knee brace is an ankle-foot orthosis [AFO]).

A Specific shoes can be used by themselves or in conjunction with foot orthoses.

B Extra-depth shoes with a high toe box designed to dissipate local pressures over bony prominences are recommended for diabetic patients.

C The plantar surface of an insensate foot is protected by use of a pressure-dissipating material. A paralytic or flexible foot deformity can be controlled with more rigid orthoses.

D SACH heels absorb the shock of initial loading and lessen the transmission of force to the midfoot as the foot passes through the stance phase.

E A rocker sole can lessen the bending forces on an arthritic or stiff midfoot during midstance, as the foot changes from accepting the weight-bearing load to pushing off. It is useful in treating metatarsalgia, hallux rigidus, and other forefoot problems. For the rocker sole to be effective, it must be rigid.

F Medial heel out-flaring is used to treat severe flatfoot of most causes. A foot orthosis is also necessary.

A Most foot orthoses are used to align and support the foot; prevent, correct, or accommodate foot deformities; and improve foot function.

B Three main types of foot orthosis are used: rigid, semirigid, and soft.

1. Rigid foot orthoses limit joint motion and stabilize flexible deformities.

2. Semirigid orthoses have hinges and allow dorsiflexion plantar flexion of the ankle, or both.

3. Soft orthoses have the best shock-absorbing ability and are used to accommodate fixed deformities of the feet, especially neuropathic, dysvascular, and ulcerative disorders.

A The most commonly prescribed lower limb orthosis (AFO) is used to control the ankle joint. It may be fabricated with metal bars attached to the shoe or thermoplastic elastomer. The orthosis may be rigid, preventing ankle motion, or it can allow free or spring-assisted motion in either plane.

B After hindfoot fusions, the primary orthotic goals are absorption of the ground reaction forces, protection of the fusion sites, and protection of the midfoot.

C The thermoplastic foot section achieves mediolateral control with high trimlines.

D When subtalar motion is present, an articulating AFO permits motion by a mechanical ankle joint design.

E The primary factors in the selection of an orthotic joint include range of motion, durability, adjustability, and the biomechanical effect on the knee joint. A posterior leaf-spring AFO provides stability in stance phase.

A The knee-ankle foot orthosis (KAFO) extends from the upper thigh to the foot. It is generally used to control an unstable or paralyzed knee joint. It provides mediolateral stability with the prescribed amounts of flexion or extension control.

B A subset of KAFOs are knee orthoses, which can be made of elastic for the treatment of patellar disease or made of metal and plastic for the treatment of an unstable anterior cruciate ligament.

VI HIP-KNEE-ANKLE-FOOT ORTHOSIS

A The hip-knee-ankle-foot orthosis (HKAFO) provides hip and pelvic stability but is rarely used by paraplegic adults because of the cumbersome nature of the orthosis and the magnitude of effort in achieving minimum gains.

B In experimental studies, it is being used in conjunction with implanted electrodes and the computerized functional stimulation of paraplegic patients.

C In children with upper-level lumbar myelomeningocele, the reciprocating gait orthoses are modified HKAFOs that can be used for standing and simulated walking.

A Hinged-elbow orthoses provide minimum stability in the treatment of ligament instability.

B Dynamic spring-loaded orthoses have been successfully used in the treatment of flexion and extension contractures.

VIII WRIST-HAND ORTHOSES (WHOs)

A The most common use of wrist and hand orthoses today is for postoperative care after injury or reconstructive surgery. These devices are static or dynamic.

B The opponens splint is successful in prepositioning the thumb but impairs tactile sensation.

C Wrist-driven hand orthoses are used in lower cervical quadriplegics. They may be body powered by tenodesis action or motor driven. Weight and cumbersomeness are the major limiting factors.

A Fracture bracing remains a valuable treatment option for isolated fractures of the tibia and fibula.

B Prefabricated fracture orthoses can be used in simple foot and ankle fractures, ankle sprains, and simple hand injuries.

A Many dynamic orthoses are used by children to control motion without total immobilization.

B The Pavlik harness has become the mainstay for early treatment of developmental dislocation of the hip.

C Several dynamic orthoses have been used for containment in Perthes disease.

1. Numerous orthoses are used to immobilize the cervical spine.

2. Effective immobilization ranges from the various types of collars, to posted orthoses that gain purchase about the shoulders and under the chin, to the halo vest, which achieves the most stability by the nature of its fixation into the skull.

section 5 Surgery for Stroke and Closed-Head Injury

1. Interventional modalities may include orthotic prescription, serial casting, and motor point nerve blocks with short-acting (bupivacaine HCl) or long-acting (phenol 6% in glycerol or botulinum toxin type A [Botox]) agents.

2. Splinting a joint (e.g., the ankle) in the neutral position is not sufficient to prevent the development of a contracture (e.g., an equinus contracture).

3. When functional joint ranging is insufficient to control the deformity, intervention is often indicated.

4. Local anesthetic injection to the posterior tibial nerve or sciatic nerve before casting relieves pain and allows for maximum correction of the deformity.

5. Open nerve blocks may be warranted to avoid injecting mixed nerves with large sensory contributions.

B Prerequisites for surgical treatment:

1. Surgical intervention in adult-acquired spasticity should be delayed until the patient achieves maximal spontaneous motor recovery (6 months for stroke and 12 to 18 months for traumatic brain injury).

2. When patients reach a plateau in functional progress or the deformity impedes further progress, intervention may be considered.

3. Invasive procedures in this population should be an adjunct to a standard functional rehabilitation program, not an alternative.

4. When surgery is considered as a method of improving function, patients should be screened for cognitive deficits, motivation, and body image awareness.

Patients should not be confused and must have adequate short-term memory and the capacity for new learning.

Patients should not be confused and must have adequate short-term memory and the capacity for new learning.

In addition to specific cognitive strengths, motivation is necessary for patients to use functional gains and participate in their rehabilitation program.

In addition to specific cognitive strengths, motivation is necessary for patients to use functional gains and participate in their rehabilitation program.

Body image awareness is essential in order for surgical intervention to become meaningful and potentially beneficial. Patients who lack the awareness of a limb or its position in space should undergo therapy directed toward ameliorating these deficits before undergoing surgical intervention.

Body image awareness is essential in order for surgical intervention to become meaningful and potentially beneficial. Patients who lack the awareness of a limb or its position in space should undergo therapy directed toward ameliorating these deficits before undergoing surgical intervention.

A Balance is the best predictor of a patient’s ability to ambulate after acquired brain injury. The mainstay of treatment for the dynamic ankle equinus component of this gait deviation is to achieve ankle stability in the neutral position during initial floor contact (i.e., initial contact and stance), as well as floor clearance during the swing phase.

B An adjustable AFO with ankle dorsiflexion and a plantar flexion stop at the neutral position is often used during the recovery period, followed by a rigid AFO once the patient has reached a plateau in recovery.

C When the dynamic equinus overcomes the holding power of the orthosis and patients are unable to keep the brace in place, motor-balancing surgery is indicated.

D The equinus deformity is treated by percutaneous lengthening of the Achilles tendon.

E The dynamic varus-producing force in adults is the result of out-of-phase tibialis anterior muscle activity during the stance phase. This dynamic varus deformity is corrected by either split or complete lateral transfer of the tibialis anterior muscle.

A Nonfunctional goals: Surgical release of static contracture is generally performed to complement nursing care or hygiene when the fixed contracture or spastic component results in skin maceration or breakdown.

B Functional goals: One functional use of static contracture release is to improve upper extremity “tracking” (i.e., arm swing) during walking. Most upper extremity surgery performed in this patient population has the goal of increasing prehensile hand function. The goal may be simply to improve placement, enabling use of the hand as a “paperweight,” or to achieve improved fine motor control. In patients with prehensile potential, surgery may allow the “one-handed” patient to be “two-handed” by increasing involved hand function from no function to assistive or from assistive to independent.

1. Screening: When the goal of surgery is to improve function, patients must first be screened for cognitive capacity, motivation, and body image awareness.

Patients must have the cognitive skills and learning capability to participate in their therapy after surgery and to functionally make use of their newly acquired skills at the completion of their rehabilitation program.

Patients must have the cognitive skills and learning capability to participate in their therapy after surgery and to functionally make use of their newly acquired skills at the completion of their rehabilitation program.

If they are not motivated, they will not participate in the prolonged effort necessary to achieve meaningful functional improvement.

If they are not motivated, they will not participate in the prolonged effort necessary to achieve meaningful functional improvement.

Patients with poor stereognosis or neglect (i.e., poor body image awareness) find that the involved hand “drifts” in space and is not “available” for use if they have not been carefully trained in visual compensation techniques.

Patients with poor stereognosis or neglect (i.e., poor body image awareness) find that the involved hand “drifts” in space and is not “available” for use if they have not been carefully trained in visual compensation techniques.

2. Grading: Once it has been determined that the patient has the potential to make functional upper extremity gains with surgery, he or she is graded on the basis of hand placement, proprioception and sensibility, and voluntary motor control. Dynamic electromyography is used when delineation of phasic motor activity is essential.

3. Methods: By means of fractional musculotendinous or step-cut methods, muscle unit lengthening of the agonist-deforming muscle units is combined with motor-balancing tendon transfers of the antagonists to achieve muscle balance and improve prehensile hand function.

section 6 Spinal Cord Injury

The level at which spinal cord injury occurs determines mobility (Table 10-7).

Table 10-7![]()

Treatment of Spinal Cord Injury by Functional Level

AFO, ankle-foot orthosis; HKAFO, hip-knee-ankle-foot orthosis; KAFO, knee-ankle-foot orthosis.

A Injury at C4 and higher levels necessitates high back and head support.

B For injury at C5, mouth-driven accessories can control a motorized wheelchair. Various body-powered or motor-driven orthoses, such as a ratchet wrist-hand orthosis, can assist functional prehension.

C Manual wheelchairs and the use of a flexor hinge wrist-hand orthosis can be operated by patients with injury at C6.

D Transfers are dependent with C4-level injuries, assisted with C5-level injuries, and independent with C6-level injuries.

III ACTIVITIES OF DAILY LIVING

A Patients with injuries at the C6 level can groom and dress themselves.

B Patients with injuries at the C7 level can cut meat. Bowel and bladder function can be controlled through rectal stimulation and intermittent catheterization.

Men with spinal injuries may be impotent but can often achieve a reflex erection.

A Spinal fusion is frequently used to expedite rehabilitation and prevent the late development of pain or deformity at the fracture level. Anterior or posterior fusion, or both, with internal fixation should be performed soon after injury in order to facilitate early rehabilitation.

B Spasticity and contracture can produce hygiene problems or the development of pressure ulcers. Percutaneous (open) motor nerve blocks with phenol can be used to treat these deformities. When the deformity is a static contracture, muscle release or disarticulation may improve sitting or transfer potential.

C Tendon transfers can be used in the upper limb to eliminate the need for an orthosis or allow the patient to achieve function with an orthosis.

section 7 Postpolio Syndrome

A Polio is a viral disease affecting the anterior horn cells of the spinal cord. Postpolio syndrome is not a reactivation of the polio virus; it is an aging phenomenon by which more nerve cells become inactive. The syndrome occurs after middle age.

B Affected patients use a high proportion of their capacity for normal activities of daily living. With aging and the drop-off of muscle units, they no longer have the reserves to perform their daily activities.

A Treatment comprises prescribed limited exercise combined with periods of rest so that muscles are maintained but not overtaxed.

B Standard polio surgeries, combining contracture release, arthrodesis, and tendon transfer, are indicated when the deformity overcomes functional capacity.

C The use of lightweight orthoses is important in helping patients remain functionally independent.

Testable Concepts

• Stance phase comprises 60% of the gait cycle; swing phase comprises 40% of the gait cycle.

• During stance phase, 12% of the time is spent in double-limb support.

• The body’s center of gravity, while being propelled forward, is also subject to 5 cm vertical and 6 cm lateral displacements.

• Most muscle activity is eccentric; that is, muscle lengthens while contracting. This allows an antagonist muscle to dampen the activity of an agonist and act as a “shock absorber.” Eccentric muscle contraction is the main form of muscle activity for normal daily activities.

• Antalgic gait results in decreased stance phase to lessen the time the painful limb is loaded.

• Water walking results in a significant decrease in joint moments and total joint contact forces as a result of the effect of buoyancy.

Section 2 Amputations

• The metabolic cost of walking is increased with proximal-level amputations and is inversely proportional to the length of the residual limb and the number of functional joints preserved.

• The required increase in energy expenditure for ambulation in bilateral transtibial amputation (41%) is less than that of unilateral transfemoral amputation (65%).

• Transcutaneous partial pressure of oxygen is the factor that is most predictive of whether wound healing after amputation will be successful. Albumin is the most important laboratory value.

• Bony overgrowth is common in children, particularly in the humerus, fibula, tibia, and femur. Autologous stump-capping can prevent this complication.

• Percutaneous Achilles tendon lengthening should be performed with transmetatarsal and Lisfranc amputations to prevent the late development of equinus or equinovarus deformity.

• In Lisfranc amputations, the soft tissue at the fifth metatarsal base should be preserved because this represents the insertion site of peroneus brevis and tertius, which act as antagonists to the posterior tibial tendon. Failure to preserve these tissues results in inversion during gait.

• Syme amputation is more energy efficient than a midfoot amputation, despite the fact that it is at a more proximal level. The posterior tibial artery must be patent to ensure healing. The heel pad must be secured.

• Transtibial amputations should be closed with a long posterior myocutaneous flap. The optimal bone length is at least 12 cm below the knee joint.

• Knee disarticulation is generally used in nonambulatory patients, inasmuch as it is muscle balanced and provides an excellent weight-bearing platform for sitting and a lever arm for transfer from bed to chair. However, data from the LEAP trial have demonstrated this amputation to result in the slowest walking speed and produce the least self-reported satisfaction.

• Transfemoral amputation should be performed 12 cm above the knee joint to accommodate the prosthetic knee.

• In transfemoral amputation, adductor myodesis is crucial for maintaining femoral adduction during gait with a prosthesis. Transecting the adductor magnus results in a loss of 70% of the adductor pull.

Section 3 Prostheses

• Myoelectric prostheses are commonly used for midlength transradial amputation.

• Body-powered prostheses are used for heavy labor. The terminal device is activated by shoulder flexion and abduction.

• Short forearm amputations, elbow disarticulations, and above-elbow amputations necessitate supracondylar suspension (Munster socket) and step-up hinges to augment function.

• The SACH prosthetic foot is being discontinued because it results in overload problems in the nonamputated foot.

• A dynamic-response prosthetic foot can be either articulated or nonarticulated. Articulated feet are useful for uneven terrain. Nonarticulated long-keel feet are used for very high-demand activities.

• Prosthetic knees are used in transfemoral and knee disarticulations. Alignment stability is crucial.

• Knee center of rotation posterior to line of weight bearing promotes control in stance phase, but flexion is difficult.

• Knee center of rotation anterior to weight bearing makes flexion easier, but control is poor.

• Microprocessor knees with polycentric (four-bar linkage) configuration should be used for most ambulatory patients with transfemoral amputations.

• Stance-phase control (safety) knee prostheses are used for older patients.

• The constant-friction knee is the most common prosthetic knee in children. Its major disadvantages are that it allows only single-speed walking and relies solely on alignment for stance-phase stability; therefore, it is not recommended for older, weaker patients.

• The preferred method of suspension for transtibial prosthetic sleeves is the gel-liner with locking pin.

• Transfemoral suspension can be with or without belts and straps. Vacuum suspension requires stable body weight but avoids belts. Silesian belts prevent socket from slipping off when suction sockets are fitted to short transfemoral stumps.

• Problems are common in prosthetics. Foot placement too anterior results in increased knee extension and patellar pain. Too soft a heel results in excessive knee extension, whereas too hard a heel causes knee flexion and lateral rotation of the toes.

Section 4 Orthoses

• A rocker sole can lessen the bending forces on an arthritic or stiff midfoot during midstance, as the foot changes from accepting the weight-bearing load to pushing off.

• After hindfoot fusions, the primary orthotic goals are absorption of the ground reaction forces, protection of the fusion sites, and protection of the midfoot.

• A posterior leaf-spring AFO provides ankle stability in stance phase.

Section 5 Surgery for Stroke and Closed-Head Injury

• Surgical intervention in adult-acquired spasticity should be delayed until the patient achieves maximal spontaneous motor recovery (6 months for stroke and 12 to 18 months for traumatic brain injury).

• Equinus deformity is treated by percutaneous Achilles tendon lengthening.

• Dynamic varus-producing force in adults is the result of out-of-phase tibialis anterior muscle activity during the stance phase. This dynamic varus deformity is corrected by either split or complete lateral transfer of the tibialis anterior muscle.

Section 6 Spinal Cord Injury

• The most important functional level is C6 tetraplegia. This is the highest level at which patients can function independently, including driving an adapted vehicle.

• In C7 tetraplegia, the patient retains elbow extension, and self-hygiene is relatively easy.

• L3 paraplegia (and below) allows community ambulation with an AFO.

Inman, VT, et al. Human walking. Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins; 1981.

Ounpuu, S. The biomechanics of running: a kinematic and kinetic analysis. Instr Course Lect. 1990;39:305.