CHAPTER 15 WOUND BALLISTICS: WHAT EVERY TRAUMA SURGEON SHOULD KNOW

Although most trauma centers in the past two decades have experienced a reduction in the volume of firearm-related injuries, trauma and general surgeons still have an obligation to be familiar with the basic principles of ballistics and the management of the varieties of wounds that projectiles produce. Wounds caused by firearms will not only be encountered in urban “high-crime” areas, but will also be seen in rural areas where hunting accidents occur. Wounds encountered in a military environment have unique characteristics that are clinically important and distinct from those seen in the civilian sector. The study of wound ballistics is an essential part of the general and trauma surgeon’s training.

FIREARM AND PROJECTILE DESIGN

Although there are many variables, the muzzle velocity (speed of the bullet as it leaves the barrel) and the bullet characteristics such as mass and deformability are the most important determinants of the wound that a particular weapon will produce (Table 1). The muzzle velocity is determined by the caliber of the bullet, the capacity of the casing (amount of powder), and gun barrel length. The bullet’s velocity rapidly increases as it travels down the barrel, but gradually slows upon meeting air resistance once it has exited. Handguns generally accept smaller bullets with less powder and have shorter barrels than rifles, and therefore produce projectiles of considerably less velocity (Table 2).

| Bullet Design |

| Caliber (diameter) |

| Mass |

| Shape (profile) |

| Jacket |

| Pellets |

| Powder (amount and type) |

| Weapon Design |

| Barrel length |

| Rifling |

| Single shot |

| Automatic |

| Semi-automatic |

| Portability (weight and size) |

| Victim |

| Position |

| Distance from weapon |

| Location of wound |

| Tissue characteristics (bone, muscle, vessel, organ) |

Table 2 Muzzle Velocity by Gun and Bullet Type

| Handguns | M/sec |

|---|---|

| .38 special | 290 |

| .44 | 305 |

| 9 mm | 315 |

| .44 magnum | 420 |

| Rifles | |

| .22 long | 380 |

| 30.06 | 890 |

| .308 (7.62 mm) | 860 |

| Military | |

| .223 (M-16) | 950 |

| .30 (AK-47) | 720 |

| .50 (Browning) | 850 |

The mass of the bullet is determined by its caliber (diameter), length, and the density of its metal components. Because of its heavier mass, and therefore its increased energy per given velocity, lead is the principal element of most bullets. Lead, however, is a relatively soft metal that deforms readily during high-velocity flight. “Jacketed” bullets have a lead body covered with metal alloys that prevent deformation during flight, and therefore help the bullet retain speed and accuracy over a long distance. Conventionally jacketed bullets will deform when they strike dense tissue, but bullets with thicker jackets are intended to retain their shape and therefore penetrate deeply into large game animals such as elephants (Figure 1). Bullets that deform upon striking the body will cause considerably more collateral tissue damage by direct contact, cavitation, and shock waves than nondeformable bullets. Fragmentation of bullets will also occur when the bullet strikes bone and will add to the damage by shredding surrounding tissue (Figure 2).

HANDGUNS

Nonetheless, several measures designed to increase the wounding potential or “stopping-power” of handguns are available and will be encountered. These include “hollow-point” bullets designed to expand (Figure 3, right) and Glaser Safety Slugs® designed to disintegrate into tiny pellets after impact (Figure 4). The Glaser Safety Slug® is marketed to law enforcement and security personnel who need to immobilize a human target in a crowded environment such as an airport or an airplane without concern of overpenetration or ricochet into innocent bystanders. “Magnum” handguns have extra powder and longer barrels that will produce a devastating wound at close range. Fortunately, magnum editions are not as commonly seen as regular handguns because they are expensive, heavy, and difficult to master.

Indications for operation of handgun wounds of the neck, chest, and abdomen would include mandatory exploration for Zone II neck injuries, selective exploration of the chest based on hemorrhage, and mandatory exploration of all abdominal penetrations except tangential injuries that do not penetrate the fascia and selective liver injuries. Patients with bullet entrance sites below the nipple on the chest require abdominal exploration if the abdomen is tender, a diagnostic peritoneal lavage is suspicious, or the diaphragm is not well visualized on radiograph. Stable patients with right upper quadrant wounds may be selectively evaluated by CT scan and managed nonoperatively if the bullet clearly injures only the liver. Laparoscopy may be used to evaluate the diaphragm in stable, nontender patients with chest wounds or as an adjunct to nonoperative management of liver penetrations that result in bile leaks.

HUNTING RIFLES

Civilian rifle wounds, such as those resulting from hunting accidents, are among the most destructive injuries seen by surgeons. The increased amount of gunpowder contained in the bullet case and the enhanced length of the barrel that exposes the bullet to the force of the powder blast for a longer distance leads to dramatically more projectile acceleration than is possible with a handgun (Figure 5). Rifling, the barrel’s internal spiraling grooves, causes the bullet to spin and consequently improves distance and accuracy. The average muzzle velocity of a 30-06 hunting rifle is 890 m/sec and may maintain up to 90% of its kinetic energy at 100 m. A rifle wound to an extremity, whether close range or distant, will destroy soft tissue, bone, and vessels, and cause dramatic hemorrhage that may need to be controlled with direct pressure or a tourniquet at the scene (see Figure 2).

Because of the potential for extensive damage to an extremity struck by a rifle bullet, plain radiographs looking for fractures, operative wound exploration with debridement, and intraoperative angiograms are highly recommended. Even if the overlying skin is uninjured, the soft tissue hidden beneath may be irreversibly damaged. All devascularized tissue and pieces of clothing should be removed. Serial debridements at daily intervals may be necessary to identify all devascularized tissue. Abdominal gunshot wounds from hunting rifles are best managed by open abdomen techniques with second-look operations if several organs are simultaneously injured.

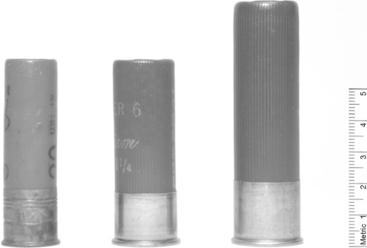

SHOTGUNS

Shotguns and their shells come in four main sizes: .410 juvenile, 20-gauge, 12-gauge, and the 10-gauge (Figure 6). Pellets are of variable sizes and are made of lead or steel. Heavier lead pellets scatter less than steel pellets, but are illegal for shooting waterfowl. Slugs are also available for shotguns and are commonly used for game hunting in some states, such as New Jersey (Figure 7). The shotgun is ineffective against humans at distances greater than 10 or 15 yards (30–45 feet), but close range (<4 feet) blasts are 85% fatal. These wounds are extremely morbid and often require several operations and multidisciplinary management. Pellets spread in every direction and strike multiple types of tissue, but fortunately because of their small mass the damage potential of the shot dissipates quickly. Pellets may enter arteries and veins and embolize peripherally or centrally. A search for the plastic insert dispelled from the shell and pieces of the patient’s clothing hidden in the wound is advised in close-range cases. There is no indication to remove all the pellets—lead poisoning does not occur from pellets or bullets left permanently in human tissue.

Figure 6 20-gauge, 12-gauge, and 10-gauge shotgun shells compared (left to right).

(Bullets courtesy of Gerald Warnock, MD, Portland, OR.)

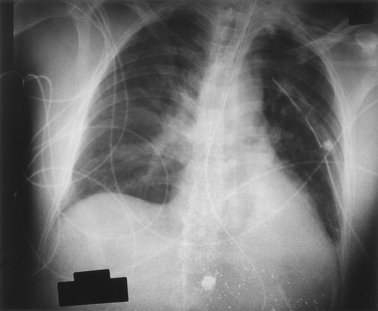

Thoracic wounds created by close-range shotgun blasts may be challenging to cover if part of the chest wall is lost—diaphragm transposition or emergent muscular flaps have been described. Abdominal wounds are best managed with serial operations and debridement through an open abdomen mesh prosthesis. Extremity shotgun blasts usually require wound exploration and debridement with intraoperative angiograms.

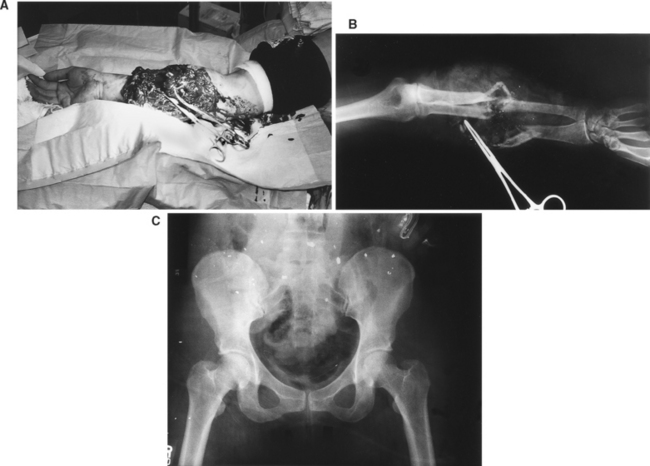

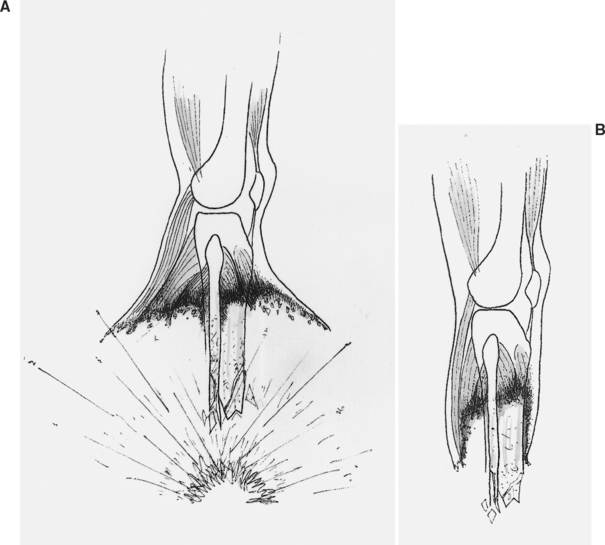

LANDMINES AND IMPROVISED EXPLOSIVE DEVICES

The detonation of a concealed explosive device such as a conventional landmine or an improvised explosive device (IED) usually results in the immediate amputation or at least partial amputation of the triggering extremity. Exsanguination from major vessel injury is possible, and therefore a field tourniquet may be necessary. Fragments of metal and debris will also shower the contralateral extremity, perineum, torso, and face. The current military standard for operative management is damage control—repeated debridements of devascularized tissue and the use of external fixators for bone stability are recommended. Conventional landmines triggered by the foot will cause an umbrella effect that spares the skin and subcutaneous tissue of the lower leg while destroying underlying muscle and bone (Figure 8A). The overlying skin will hide significant destruction and contamination beneath (Figure 8B). Aggressive debridement to prevent infection tracking along the popliteal vessels and neural sheaths is advised. Robin Coupland of the International Red Cross makes an argument, however, to conserve the partially protected gastrocnemius muscle for reconstruction.

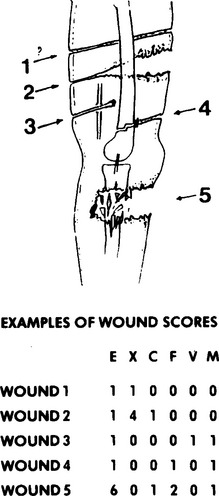

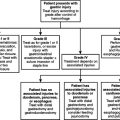

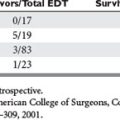

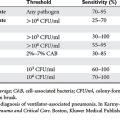

RED CROSS WOUND CLASSIFICATION

Classification of wounds has merit since in practical terms it may be difficult to determine the exact type of weapon used. The International Committee of the Red Cross has adopted Coupland’s wound description method. There are six main criteria that are used to divide wounds into three grades and four types. At first glance the system seems formidable, but surgeons of the Red Cross, who classify about 4000 wounds per year, have accepted the system and are developing guidelines based on it. Wounds are scored on initial assessment or after surgery by entry size (centimeters), exit size (centimeters), cavity size (fingers), fractures, vital structures (brain, viscera, major vessels), and metallic body (intact bullet vs. fragments). The categories are E, X, C, F, V, and M, respectively (Figure 9). The advantages of uniform classification of wounds for research purposes are multiple.

Barach E, Tomlanovich M, Nowak R. Ballistics: a pathophysiologic examination of the wounding mechanisms of firearms (part I). J Trauma. 1986;26:225-235.

Bender JS, Lucas CE. Management of close-range shotgun injuries to the chest by diaphragmatic transposition: case reports. J Trauma. 1990;30:1581-1584.

Coupland RM. War Wounds of Limbs: Surgical Management. Oxford: Butterworth-Heinemann, Ltd., 1993.

Coupland RM, Loye D. The 1899 Hague Declaration concerning expanding bullets: a treaty effective for more than 100 years faces complex contemporary issues. Int Rev Red Cross. 2003;849:135-142.

Fackler ML. Wound ballistics: a review of common misconceptions. JAMA. 1988;259:2730-2736.

Fackler ML, Surinchak JS, Malinowski JA, Bowen RE. Bullet fragmentation: a major cause of tissue disruption. J Trauma. 1984;24:35-39.

Long D. AK47: The Complete Kalashnikov Family of Assault Rifles. Boulder, CO: Paladin Press, 1988.

Marshall TJ. Combat casualty care: the Alpha Surgical Company experience during Operation Iraqi Freedom. Mil Med. 2005;170:469-472.