8 Wind and gas

Introduction

Many patients present complaining of ‘excessive gas’, which can indicate excessive passage of wind through the mouth or anus, abdominal bloating or audible bowel sounds (borborygmi). In population studies about 20% of individuals report abdominal bloating. The causes of a sensation of excess gas include air swallowing or ingestion of poorly absorbed but fermentable foods such as baked beans, bran or brassica vegetables. Other causes include lactose intolerance (due to lactase deficiency; see ch 18) or malabsorption (e.g. due to coeliac disease, giardiasis or bacterial overgrowth). Functional gastrointestinal disease can also produce a sensation of excessive gas.

History

An accurate history is essential. Determine if the problem is excessive belching (usually due to air swallowing), abdominal bloating or distention, or excessive flatus. Check for evidence of irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), which is characterised by abdominal pain and discomfort with altered bowel habit, a sensation of incomplete rectal evacuation and bloating which is often present in the afternoon. Enquire about the presence of alarm symptoms such as vomiting, bleeding or weight loss and investigate these symptoms if they are present. An adequate dietary history is required. In adults, lactose intolerance is the usual status for non-Caucasians. In general, origin from Northern Europe usually indicates normal lactase levels.

Investigations

X-ray and endoscopy

A plain abdominal x-ray is not normally required. Most patients with bloating and abdominal distention have a normal x-ray. The aim of the x-ray is to confirm the possibility of intestinal obstruction. An upper gastrointestinal endoscopy is required if there are alarm features such as vomiting and weight loss. Mucosal biopsies could be considered to exclude giardiasis or coeliac disease. The lactase level can be quantified on small bowel biopsy specimens.

Breath hydrogen testing for lactose intolerance

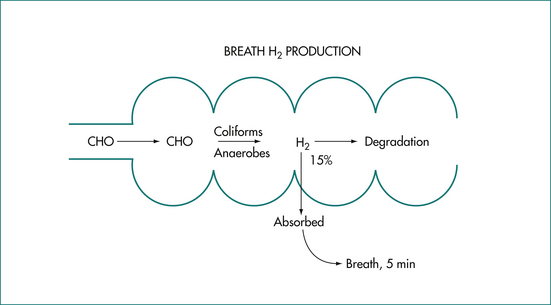

Gas production in the human gut is determined by two factors: first, the amount of fermentable substrate that evades digestion in the small bowel and reaches the colon (Fig 8.1); and, secondly, by the individual characteristics of the colonic flora. Lactose intolerance is due to a deficiency of the enzyme lactase in the brush-border membrane of the intestinal villous cell and is manifested by abdominal cramps, borborygmi, bloating, excessive flatus (bacterial fermentation) and diarrhoea (osmotic effect) following milk ingestion. Primary lactase deficiency is genetically determined and lactose intolerance occurs from late childhood in populations who are not of northern European ancestry.

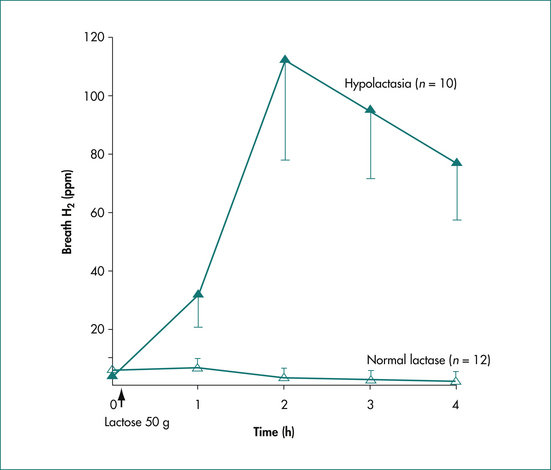

The breath hydrogen (H2) test following a 50 g lactose challenge is a non-invasive, sensitive and specific method to identify subjects with lactase deficiency (Fig 8.2). The subject is prepared by an overnight fast following a meal of meat and rice and avoidance of foods rich in starch and fibre (to reduce baseline H2 levels): smoking is prohibited. A baseline breath test is obtained and then a 50g test load of lactose is administered. Breath samples are obtained at half-hourly intervals for 4 hours. An abnormal result is characterised by breath hydrogen exceeding 20 parts per million over the baseline. Lactose-intolerant patients may experience the usual symptoms listed above. The majority of patients with lactase deficiency have adjusted their diet and generally avoid symptoms associated with lactose-containing foods. Management is by the use of commercial milk products containing lactase, hard and mature cheeses (minimal residual lactose) and yoghurt (auto-digesting).

Breath hydrogen testing for bacterial overgrowth of the small intestine

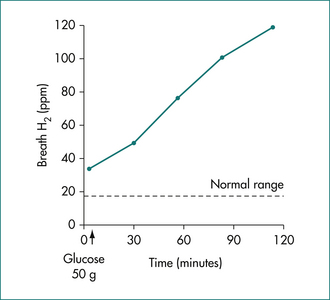

The syndrome of bacterial overgrowth of the small intestine is characterised by the presence of diarrhoea, malabsorption and weight loss. Potential causes include altered anatomy (e.g. a blind loop associated with a Billroth II gastrectomy) and altered motility (e.g. scleroderma or intestinal pseudo-obstruction). Confirmation of the diagnosis is by demonstration of increased microbial numbers (over 105 organisms/mL) in the proximal small intestine. Alternative, non-invasive techniques use the metabolic action of the bacteria. These indirect diagnostic tests include measurement of the production of H2 after exposure of a fermentable substrate (e.g. glucose or rice flour) to pathologically high levels of intestinal bacteria. A positive test is characterised by a high fasting breath H2 level after dietary preparation as mentioned above and the finding of a rise in breath hydrogen of at least 12 ppm within 2 hours of a 50 g glucose challenge (Fig 8.3).

Incompletely absorbed dietary carbohydrates

Fructose is a monosaccharide present in fruits (juices and dried fruits), honey and table sugar. Sorbitol is a sugar found naturally in various fruits, for example apples, pears and prunes. Both fructose and sorbitol are used as artificial sweeteners in many sugar-free mints and gums. Incomplete absorption can result in fermentation in the colon with resulting abdominal discomfort, bloating and diarrhoea.

Laboratory Tests

These tests are rarely required. If organic disease is suspected check the haemoglobin, iron, red cell folate and vitamin B12 levels. Check the serum albumen level for evidence of malabsorption. The tissue transglutaminase (TTG IgA) antibody is a sensitive and specific test for coeliac disease.

Composition

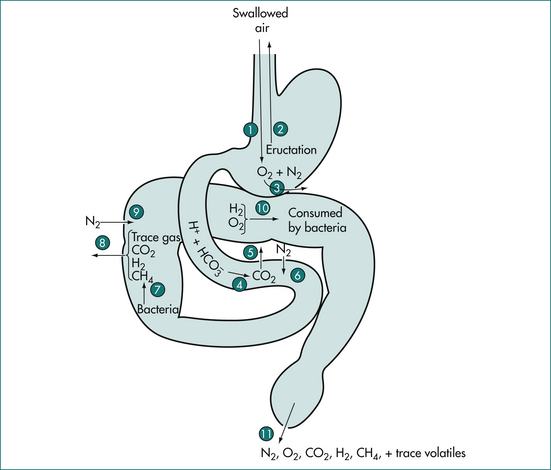

The composition of gases in the gut varies with the site of sampling. For example, nitrogen concentration in the human stomach approaches atmospheric, suggesting that it originates from swallowed air. The five gases nitrogen (N2), oxygen (O2), carbon dioxide (CO2), hydrogen (H2) and methane (CH4) comprise about 99% of intestinal gas (Table 8.1, Figure 8.4). Nitrogen is the predominant gas and O2 is present in low concentrations. Carbon dioxide in the upper small bowel reflects the interaction of gastric acid and bicarbonate secretion from the pancreas, biliary tree and small intestine. Most of the small bowel CO2 appears to be absorbed. Carbon dioxide in the lower small bowel results from the interaction of bicarbonate and organic acids. Breath CO2 can be studied by the use of isotopic labelling of the carbon atoms. Three gases (CO2, H2 and CH4) are produced in the gut by bacterial action on unabsorbed carbohydrate. Hydrogen production is usually limited to the colon and is dependent on the ingestion of fermentable substrates, which escape absorption in the small intestine (Fig 8.1). In general, about 90% of most staple carbohydrate is absorbed in the small bowel but 10% escapes absorption and passes to the colon. Baked beans contain unabsorbable oligosaccharides such as stachyose and raffinose and these produce large quantities of gas after interaction with colonic bacteria. About 15% of hydrogen production in the colon is absorbed into the circulation and expired from the lungs. About 30% of normal individuals produce significant amounts of CH4. The production is constant and unrelated to food intake.

| Gas∗ | Origin | |

|---|---|---|

| N2 O2 |

} | Swallowed air, diffusion from blood |

| CO2 | Secretion, diffusion, bacterial metabolism | |

| H2 CH4 |

} | Bacterial metabolism |

∗ Plus traces of odiferous gases that are socially significant.

Symptoms Associated with Intestinal Gas

The origin of odoriferous gases after garlic ingestion has been studied by Suarez and colleagues from Minneapolis. The halitosis initially originates from the mouth and subsequently from the gut (metabolism in the colon causing large concentration in alveolar air). Oral hygiene may reduce the halitosis from the mouth and manipulation of the diet may limit gas production from the gut flora.

Based on observations in healthy young students the frequency of passage of flatus is 14 per day. The frequency and volume of flatus varies widely, and depends on the composition of the colonic flora. Maximum gas production occurs after poorly digested food such as baked beans and brassica vegetables (cabbage, brussels sprouts and broccoli), which should be avoided by patients with excessive flatus. Least rectal gas follows ingestion of carbohydrates such as rice flour, which is fully absorbed in the small intestine. The addition of fibre in patients with IBS is an important therapeutic option but can temporarily aggravate abdominal discomfort and bloating for 2–3 weeks.

Key Points

Accarino A., Perez F., Azpiroz F., et al. Abdominal distention results from caudo-ventral redistribution of contents. Gastroenterology. 2009;136(5):1544-1551.

Anderson I.H., Levitt A.S., Levitt M.D. Incomplete absorption of the carbohydrate in all purpose wheat flour. N. Engl J Med. 1981;304:891-892.

Azpiroz F., Malagelada J.R. Abdominal bloating. Gastroenterology. 2005;129(3):1060-1078.

Kerlin P., Phillips S.F. Differential transit of liquids and solid residues through the ileum of man. Am J Physiol. 1983;245:G38-G43.

Kerlin P., Wong L. Breath hydrogen testing in bacterial overgrowth of the small intestine. Gastroenterology. 1988;95:982-988.

Kerlin P., Wong L., Harris B., et al. Rice flour, breath hydrogen and malabsorption. Gastroenterology. 1984;87:578-585.

Lasser R.B., Bond J.H., Levitt M.D. The role of intestinal gas in functional abdominal pain. N Engl J Med. 1975;293:524-556.

Ohge H., Furne J.K., Springfield J., et al. Effectiveness of devices perported to reduce flatus odour. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005;100(2):397-400.

Suarez F., Springfield J., Furne J., et al. Differentation of mouth versus gut as site of origin of odiferous breath gases after garlic ingestion. Am J Physiol. 1999;276:G425-G430.