1 Heartburn, regurgitation and non-cardiac chest pain

Case

A 52-year-old male presents with intermittent, retrosternal burning. This tends to occur after meals, but occasionally is worsened by exercise. He gets relief with drinking water and with antacids. The symptom has been present for years, but has become progressively more severe over the past 6 months. He has also developed what he describes as ‘slow swallowing’, which on further questioning sounds like mild dysphagia to solids that happens about once a week. He has gained 10 kg in the past year and has no evidence of gastrointestinal bleeding. His examination is unremarkable except for mild obesity (BMI = 31) and his stool has no occult blood. He had a normal exercise stress test as part of a recent executive physical.

History

Heartburn

The timing of heartburn is characteristic. It occurs intermittently, either postprandially or when the patient bends forward or lies flat in bed, when the gastric contents are level with, or above, the lower end of the oesophagus. When it occurs postprandially, it is most commonly in the early postprandial period, 5 to 30 minutes after a meal. The postural changes that initiate heartburn do so by raising the level of the gastric contents above the level of the gastro-oesophageal junction. The duration of an individual attack, when untreated, rarely exceeds an hour.

Complications of acid regurgitation

Severe acid regurgitation can be associated with other problematic symptoms including choking attacks, cough, asthma, hoarseness of voice, a foul taste in the mouth in the morning, bad breath, a sore tongue, dental caries and nasal aspiration. Some patients complain of waking up episodically with a sensation of choking such that they will cough vigorously, but rarely produce sputum, get up out of bed and even go to an open window to catch their breath. These symptoms subside fairly rapidly. For some, the history suggesting episodic tracheal aspiration will be less dramatic. They may describe a chronic cough, perhaps worse in the morning, but without sudden exacerbations. When that is the case, other causes of cough will need to be considered and excluded as part of a respiratory work-up. Asthma usually has an allergic basis but, occasionally, can be precipitated by gastro-oesophageal reflux. Such patients may present later in life without any obvious cause for obstructive airways disease. In these patients, the symptoms of gastro-oesophageal reflux are commonly not severe. Acid regurgitation can result in a chemical laryngitis and cause hoarseness of voice. Usually the regurgitation occurs at night so hoarseness is most evident in the morning, and gradually settles as the day passes. Similarly, waking up with a foul taste in the mouth or bad breath can be attributed to nocturnal gastro-oesophageal reflux. Nasal aspiration is a particularly unpleasant consequence of regurgitation, again usually occurring at night.

Pathophysiology of GORD

Most of the fluid volume of refluxate is promptly cleared from the oesophagus by one or more swallows. Small amounts of residual acid are neutralised by weakly alkaline saliva with subsequent swallows. Clearance is delayed during sleep when swallowing is less reliably triggered by reflux. Smoking exacerbates the effects of reflux by inhibiting salivation, thereby delaying acid clearance.

Investigation of Heartburn and Acid Regurgitation

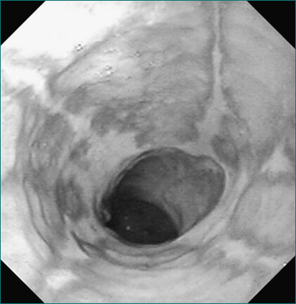

Upper gastrointestinal endoscopy

The characteristic endoscopic signs of reflux oesophagitis are shown in Table 1.1 and Figure 1.1. As mentioned above, there is only a weak correlation between the severity of oesophageal acidification and the degree of peptic oesophagitis. On the other hand, it is clear that more severe grades of esophagitis are more difficult to heal. Oesophagitis should never be diagnosed based on anything short of mucosal erosion and never should be based on erythema of the distal oesophagus. The diagnostic endoscopic examination is always carried as far as the first part of the duodenum looking for incidental pathology. The finding of a chronic duodenal ulcer is significant as this may be the underlying cause of gastro-oesophageal reflux symptoms (see Ch 5).

Table 1.1 Classification of reflux at endoscopy (Los Angeles—LA—System)

| Grade | Feature |

|---|---|

| Grade A | At least one mucosal break (erosion) each ≤ 5 mm |

| Grade B | At least one mucosal break > 5 mm but not continuous between the tops of two mucosal folds |

| Grade C | At least one mucosal break that is continuous between the tops of 2 mucosal folds, but which is not circumferential (< 75%) |

| Grade D | Circumferential mucosal break (≥ 75%) |

Oesophageal biopsy at upper gastrointestinal endoscopy

These microscopic findings can be relatively difficult to quantify on routine biopsy specimens and the diagnostic value of these findings continues to be disputed, so biopsy is not recommended routinely. Recently, some experts have suggested obtaining midoesophageal biopsies in patients with any unexplained oesophageal symptom (especially dysphagia) to search for histological evidence of eosinophilic oesophagitis (Ch 2).

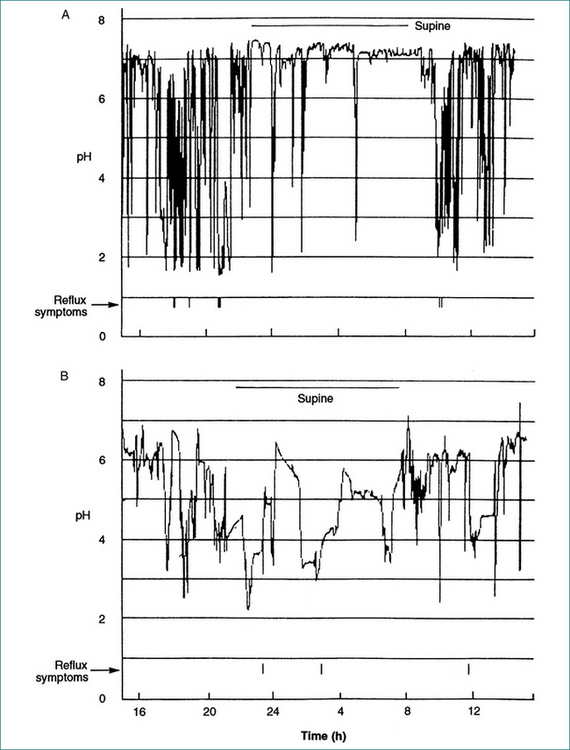

Ambulatory reflux monitoring

Episodes of gastro-oesophageal reflux result in acidification of the distal oesophagus. Neutral pH is restored by oesophageal peristalsis. These episodes can be monitored and recorded by placement of a pH microelectrode in the distal oesophagus. In the past this test required prolonged nasal intubation, which is unpleasant. That discomfort can now be avoided by attaching the pH electrode to the lower oesophageal mucosa endoscopically. The pH recording then occurs by telemetry. The electrode subsequently detaches and passes spontaneously. Summation of the duration of episodes over an extended period, usually 24–48 hours, gives a measure of the underlying pathophysiological process, which can be used to score the severity of the disease. Further, a correlation between symptoms and episodes of oesophageal acidification can be established (see Fig 1.2). The test is not required for diagnosis in the majority of patients with typical symptoms of reflux in whom the diagnosis can be made either endoscopically or, if there is no oesophagitis, on the basis of a successful therapeutic trial with a course of antisecretory treatment.

Bernstein testing

Bernstein testing is a test of mucosal sensitivity that is of mostly historical interest, although it may be available in a few referral centres. It involves transnasal oesophageal intubation and perfusion of the distal oesophageal mucosa with dilute (0.1 M) hydrochloric acid alternating with placebo (normal saline). The test is considered positive if the acid produces the patient’s symptoms and the saline does not. It can be complementary to pH monitoring in patients whose atypical symptoms, particularly chest pain, are infrequent and do not occur during a pH-monitoring study.

Oesophageal manometry

This test has no routine diagnostic role in the evaluation of symptoms of GORD unless antireflux surgery is being considered, where manometry is used to exclude achalasia and to tailor the tightness of the repair. It may sometimes be useful in the evaluation of patients with symptoms of dysphagia in addition to those of heartburn and regurgitation, where a barium swallow and endoscopy have been normal and the dysphagia remains unexplained (see Ch 2).

Treatment

Clinical management of heartburn and regurgitation

The intensity of reflux symptoms varies from a mild, occasional discomfort, for which the patient may want little more than antacid and reassurance, to a daily, incapacitating pain that prevents normal activity. Management needs to be commensurate with the magnitude of the clinical problem. Unlike duodenal ulceration, GORD is usually a persistent condition without exacerbations and remissions. Drug therapy has a hierarchy (see Box 1.1). Oesophagitis indicates a need for therapy to heal the mucosa and maintain healing; virtually all patients with severe oesophagitis (LA grade C and D oesophagitis; see Table 1.1) will relapse if medical therapy is stopped, as will most (80%) with milder oesophagitis. A review of the clinical management principles for patients with gastro-oesophageal reflux is presented in Table 1.2.

Box 1.1 Effectiveness of drugs for gastro-oesophageal reflux

| Twice-daily proton pump inhibitors |  |

| Once-daily proton pump inhibitor combined with H2-receptor antagonist | |

| Once-daily proton pump inhibitors | |

| Standard-dose H2-receptor antagonists | |

| Antacids |

Table 1.2 Features of clinical management of gastro-oesophageal reflux

| Patient-directed treatment | Doctor-directed treatment |

|---|---|

Patient-directed therapy

Doctor-directed treatment

Some patients will have symptoms and/or oesophagitis that do not respond to standard doses of proton pump inhibitors. A common approach is to increase the dose to twice daily (before meals) for an additional 4–8 weeks to see if the disease is brought under control. This approach has not been tested in well-designed trials and it is not clear what proportion of patients will respond. An additional nocturnal dose of H2-receptor antagonists may be of assistance, but benefits often wear off if given continuously. An alternative is to study the patient using ambulatory reflux testing to either confirm control of acid (on therapy testing) or to determine if they actually have the disease (off-therapy testing or perhaps combined impedance/pH testing). The addition of a prokinetic agent is an attractive concept, but none of the currently available agents have been proven to be effective as either mono or ‘add-on’ therapy in this situation. There are several agents in development that may inhibit transient LES relaxation. Some of the possibilities to be considered when a patient is ‘failing’ proton pump inhibitor therapy are outlined in Table 1.3.

Table 1.3 Failure of proton pump inhibitor therapy to control gastro-oesophageal reflux symptoms: management approach

| Mechanism to consider | Management |

|---|---|

| Misdiagnosis | Review history and investigations. |

| Not taken before meals | Advise taking 30 minutes prior to a meal. |

| Inadequate dosing | Trial twice-daily therapy. |

| Nocturnal acid breakthrough | Twice-daily proton pump inhibitor; if that fails, H2-receptor antagonist before bed as needed; consider surgery. |

| Acid hypersecretion | Exclude Zollinger-Ellison syndrome. |

| Drug resistance | Very rare; switch to H2-receptor antagonist or consider surgery. |

| Oesophageal hypersensitivity | Add a low-dose tricyclic antidepressant. |

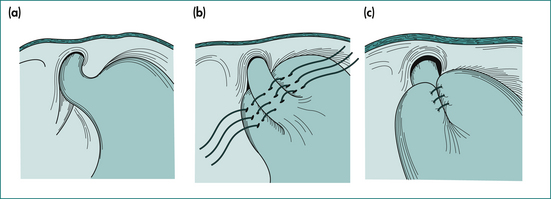

Patients for whom medical therapy results in incomplete resolution of symptoms (especially regurgitation) can achieve that end point with antireflux surgery. Nevertheless, the majority of patients presenting for surgery present because they are keen to achieve long-term cure, without need for continuing medical therapy and follow-up. Most report the loss of reflux symptoms without the need to take medication from the day of surgery. There is complete control in up to 90% of patients with typical symptoms that responded to acid suppression in the hands of an experienced surgeon. However, in some studies up to 50% of cases eventually will have reintroduction of acid suppression therapy over the long term. The risk of postoperative sequelae has limited the more widespread utilisation of antireflux surgery. The more troublesome of these are painful abdominal distension (gas bloat), persistent dysphagia and, less commonly, persistent diarrhoea.

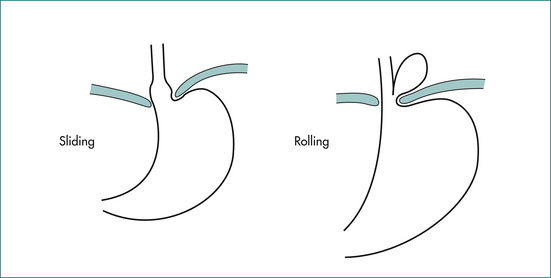

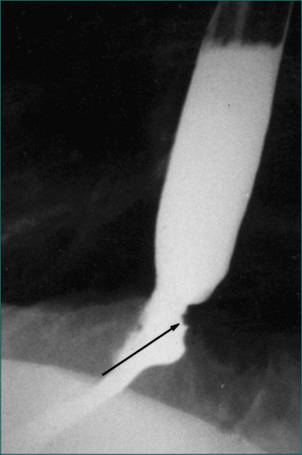

The surgical approach for most will be laparoscopic. This conveys the advantages of less postoperative pain and early return to full activity. The procedure involves an initial restoration of normal anatomical relationships by reduction of the commonly associated sliding hiatus hernia (see Fig 1.3A) and then wrapping of the lower oesophageal sphincter region with the gastric fundus (see Fig 1.3B). There is still debate as to whether the fundoplication should be complete as shown in Figure 1.3B, or whether the wrap should be incomplete—surrounding less than the 360° circumference of the lower oesophageal sphincter. Current data suggest that patients having the so-called incomplete fundoplication are more satisfied with the outcome because of an apparent reduction in sequelae, even though the long-term control of reflux might not be quite as good as with complete fundoplication. Endoscopic therapies to treat gastro-oesophageal reflux, including radiofrequency therapy, injection of biopolymer and endoscopic sewing around the lower oesophageal sphincter, have been studied. Of these, the systems that place sutures to form a ‘plication’ at the LOS are the only currently available options, while most of the others have been removed because of lack of efficacy, unacceptable side effects or both.

Clinical management of dysphagia associated with reflux symptoms

Hiatus hernia

A hiatus hernia is a protrusion of intraabdominal contents through the oesophageal hiatus in the diaphragm. Two main types of hiatus hernia are recognised radiologically (see Fig 1.3A).

Routine (sliding or fixed) hiatus hernia

This type of hernia is extremely common (in 10–15% of the population) and often asymptomatic. Its prevalence increases with age. It occurs as a result of circumferential telescoping of the segment of stomach that lies just distal to the lower oesophageal sphincter through the oesophageal hiatus. This type of hernia is not prone to obstruction or strangulation, so specific surgical treatment of the hernia is not required; when it is found incidentally in association with GORD, attention should be directed at treatment of the reflux disease. Herniae are more common in more severe grades of esophagitis and are almost universally present in patients with Barrett’s oesophagus.

Barrett’s oesophagus

One of the consequences of long-term gastro-oesophageal reflux is a metaplastic transformation of the stratified squamous epithelium of the distal oesophagus to a columnar type epithelium. The affected oesophagus is termed Barrett’s or columnar-lined oesophagus. The significance of Barrett’s oesophagus is its predisposition to malignant change. Clinically, much effort is expended to identify and treat such patients before they present clinically with an adenocarcinoma of the distal oesophagus (Fig 1.4), when the outlook is likely to be poor (Ch 17). It has been suggested that patients with the following characteristics are at greatest risk of developing Barrett’s oesophagus and subsequently oesophageal adenocarcinoma: long-term reflux symptoms, male sex, Caucasian race and positive family history. Despite that, some patients will have reflux symptoms that are so minor that an endoscopy is not likely to be performed on clinical grounds. As a consequence, many patients remain unaware that they carry this malignant predisposition and present at a more advanced stage.

Development of adenocarcinoma in Barrett’s oesophagus is a staged process that occurs over several years. The precursors of invasive carcinoma (low-grade and high-grade dysplasia) can be detected reliably only by histological examination of multiple samples of the columnar epithelium. There are no reliable serological markers or even endoscopic appearances, although advances in endoscopic imaging may change that in the next few years. There is no evidence that control of continuing reflux, after the metaplastic epithelial change has occurred, stops progression down the dysplastic pathway, even though this is appropriate for control of reflux symptoms. Preliminary data suggest that aspirin may slow the progression of Barrett’s oesophagus to dysplasia and is safe when combined with a proton pump inhibitor.

Non-cardiac Chest Pain

Panic attacks

Panic attacks can cause chest pain. They result in discrete periods of intense fear that occur abruptly with at least four of the following symptoms: chest pain, palpitations, sweating, trembling, shortness of breath, choking, nausea, dizziness, feelings of unreality or detachment, fear of losing control, fear of dying, paraesthesia and flushes or chills.

Oesophageal conditions

Oesophageal conditions that can cause non-cardiac chest pain, in order of importance, include:

If the patient fails a treatment trial or if the symptoms are clearly related to swallowing, an oesophageal motility test may be of benefit although the minority of patients will have a clearly definable motility disturbance. The manometric characteristics of motor disorders that may cause non-cardiac chest pain are shown in Table 1.4. Unfortunately, manometry has significant limitations in this clinical setting as it is performed in a laboratory over a short time frame (which is standard) and the chance that the abnormal manometric findings will be observed, except in the case of achalasia, is low. This likelihood can be increased by using provocative agents, such as edrophonium, or extending the period of observation utilising a portable ambulatory manometry system. Effective therapy for diffuse oesophageal spasm, nutcracker oesophagus, non-specific motility disorder and hypertensive lower oesophageal sphincter is currently not available. Therapeutic trials of nitrates or a calcium channel blocker are worthwhile, but should be discontinued if there is no apparent response.

Table 1.4 Manometric features of oesophageal motility disorders that may be associated with non-cardiac chest pain

| Disorder | Features |

|---|---|

| Achalasia (see Ch 2) |

Key Points

Cremonini F., Wise J., Moayyedi P., et al. Diagnostic and therapeutic use of proton pump inhibitors in non-cardiac chest pain: a metaanalysis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005;100:1226-1232.

Dent J., El-Serag H.B., Wallander M.A., et al. Epidemiology of gastro-oesophageal reflux disease: a systematic review. Gut. 2005;54:710-717.

DeVault K.R., Castell D.O. American College of Gastroenterology. Updated guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of gastroesophageal reflux disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005;100:190-200.

DeVault K.R., Talley N.J. Insights into the future of gastric acid suppression. Nature Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;6:524-532.

El-Serag H., Becher A., Jones R. Systematic review: persistent reflux symptoms on proton pump inhibitor therapy in primary care and community studies. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2010;32:720-737.

Johnson D.A., Fennerty M.B. Heartburn severity underestimates erosive esophagitis severity in elderly patients with gastroesophageal reflux disease. Gastroenterology. 2004;126:660-664.

Kahrilas P.J., Shaheen N.Y., Vaezi M.F., et al. American Gastroenterological Association Institute technical review on the management of gastroesophageal reflux disease. Gastroenterology. 2008;135:1392-1413.

Sharma P., McQuaid K., Dent J., et al. A critical review of the diagnosis and management of Barrett’s esophagus: the AGA Chicago Workshop. Gastroenterology. 2004;127:310-330.

Shaheen N.J., Sharma P., Overholt B.F., et al. Radiofrequency ablation in Barrett’s esophagus with dysplasia. New Engl J Med. 2009;360:2277-2288.

Wang K.K., Sampliner R.E. Updated guidelines 2008 for the diagnosis, surveillance and therapy of Barrett’s esophagus. Am J Gastroenterol. 2008;103:788-797.