48

When a baby dies

stillbirth and neonatal death

Introduction

To suffer the loss of a baby before or shortly after birth is one of the most profoundly distressing experiences, one that affects a wide community of parents and siblings, relatives and friends, for most of whom the emotional upheaval is never resolved fully.

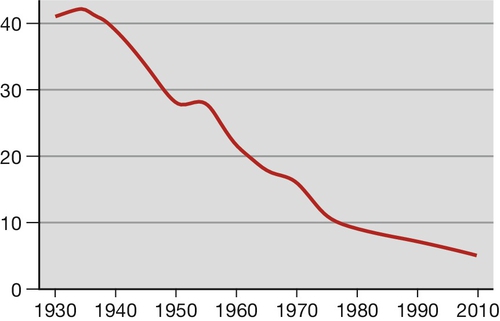

Stillbirths, babies born with no signs of life after the end of the 24th week (24 + 0), are classified as deaths before the onset of labour (late fetal death) and deaths in labour (intrapartum stillbirth). Intrapartum deaths account for about 10% of all stillbirths in the UK. The UK stillbirth rate fell greatly across the second half of the 20th century (Fig. 48.1), mainly because of improved general health, better nutrition and wider education, probably more so than the consequence of any change in antenatal care per se. Despite this large fall, about 1 in 200 maternities in developed countries still end in stillbirth, 50 times the rate of sudden unexplained deaths in infancy (SUDI). In 2010, 3710 babies were stillborn in England and Wales, more than 10 each day, on average. There are a total of 3 million stillbirths each year worldwide and in the developing world, the stillbirth rate remains high, approximately 10-fold greater than for countries with advanced healthcare systems. There are many causes (see below) but as with almost half of affected pregnancies in the UK, no adequate explanation can be provided for the parents.

Neonatal mortality, defined as death in the first 28 days of life, is divided into early deaths within the first 7 days and late deaths beyond 7 days. In 2010, there were 1657 deaths at age under 7 days in England and Wales. In developed countries, the large majority is associated with pre-term birth, which can be the result of spontaneous labour or be the consequence of elective birth because of maternal or fetal conditions. The rate of survival varies with gestation at birth and the underlying cause. As with stillbirths, there is great variation in causes and rates across the globe.

Overall, the perinatal mortality rate for England and Wales is about 7/1000 total births. This chapter provides definitions for these birth statistics as well as considering the causes, complications and comprehensive care for parents whose baby dies before or shortly after birth.

Statistics of adverse perinatal outcomes

The definitions of commonly used birth statistics are presented in Table 48.1. Perinatal mortality rate (PNMR) has been seen as a broad indicator of the quality of maternity and neonatal services, often adjusted to exclude deaths related to lethal congenital malformations that cannot be avoided. In truth, even the adjusted PNMR is of relatively limited value for clinicians interested in quality improvement. For individual units, comparisons with other units are clouded by variations in societal differences and case mix.

Table 48.1

Definitions of stillbirth and deaths in infancy

| Stillbirth (rate) | Any fetus born without signs of life, after 24 completed weeks of pregnancy (excepting fetuses that clearly died before 24 weeks, e.g. fetus papyraceous) (/1000 total births) |

| Early neonatal death (rate) | Death in the first seven days of life (/1000 live births) |

| Late neonatal death | Deaths from age 7 days to 28 completed days of life (/1000 live births) |

| Perinatal mortality (rate, PNMR) | Stillbirth or neonatal death in first week of life (combined/1000 total births) |

| Adjusted PNMR | Number of deaths/1000 live and stillbirths, excluding lethal congenital malformationsa |

| Post-neonatal death | Deaths beyond 28 days, but under 1 year of age |

| Infant death | All deaths at age under 1 year of age |

a Some authorities also exclude babies below a certain weight.

Even international comparisons of PNMR of whole populations can be misleading, as there can be:

![]() differences in the way statistics are collected

differences in the way statistics are collected

![]() differences in how gestational age is calculated

differences in how gestational age is calculated

![]() differences in social conditions that probably have more influence than health care

differences in social conditions that probably have more influence than health care

![]() differences in reproductive patterns such as the one-child policy in China

differences in reproductive patterns such as the one-child policy in China

![]() cultural infanticide of baby girls in some countries.

cultural infanticide of baby girls in some countries.

The PNMR is perhaps of most value for monitoring progress of major health initiatives in individual countries with very poor outcomes.

Emotional effects of perinatal death

The loss of a baby in late pregnancy or during the early neonatal period is nearly always accompanied by profound distress for parents and siblings, relatives and friends. For the mother especially, the feelings of loss can be compounded by vulnerability, depression and post-traumatic stress. Emotional reactions can be further heightened by prior suboptimal treatment, traumatic birth or a period of intensive critical care after the delivery. Any resolution of these feelings can be delayed by a later inability to explain the death. For carers, stillbirth and neonatal death can engender feelings that range from deep sadness, through anxiety and loss of confidence, to a sense of personal failure. All of this must be taken into full account when accompanying the parents on the journey that starts with the realization of their loss, and also when supporting staff.

Common associations and causes of stillbirth

Higher maternal age and maternal obesity are the two commonest associations. The prevalence of these factors is rising, which might explain why the stillbirth rate is no longer falling. Other associations include smoking, illicit drug use, teenage pregnancy and maternal disease, many of which are also rising in frequency.

It is not always possible to define a disease process and so descriptive categories have been identified, of which there are several classifications. The commonest method still in use is Wigglesworth’s classification, which is summarized in Table 48.2. Many categories simply describe the mode of death rather than the true underlying cause, for example hypoxia and growth restriction. Hypoxia may be chronic, in relation to placental disease, or acute such as placental abruption, cord prolapse or cord entanglement, but often the precise cause is unknown. For more details on specific causes such as antepartum haemorrhage, hypertension, medical disorders and isoimmunization, see the relevant individual chapters. A more detailed system is the ReCoDe (Relevant Condition at Death) classification developed in the West Midlands (Table 48.3). Clinicians have to be aware that the presence of a condition does not necessarily mean it is the cause of death and the authors of the ReCoDe system emphasize that.

Table 48.2

Wigglesworth’s classification of stillbirths

| Category | Comment |

| Unexplained | Largest single category Mostly normally-grown babies at term |

| Malformations | Lethal or severe |

| Intrapartum asphyxia or trauma | Related to abruptions, cord prolapse, shoulder dystocia, etc. |

| Immaturity | More usually a cause of neonatal death |

| Fetal infection | May be acute bacterial or chronic viral, protozoal, etc. |

| Other causes | Twin-to-twin transfusion, tumours, isoimmunization |

Table 48.3

ReCoDe classification of stillbirths

| Group | Subgroups |

| Fetal | Lethal congenital anomaly Infection Non-immune hydrops Isoimmunization Fetomaternal haemorrhage Twin–twin transfusion Fetal growth restrictiona |

| Umbilical cord | Cord prolapse Constricting loop or knotb Velamentous insertion Other |

| Placenta | Placental abruption Placenta praevia Vasa praevia Other ‘placental insufficiency’c Other |

| Uterus | Rupture Anomalies Other |

| Amniotic fluid | Chorioamnionitis Oligohydramniosb Polyhydramniosb Other |

| Mother | Diabetes and thyroid diseases Essential hypertension and hypertensive diseases in pregnancy Lupus or antiphospholipid syndrome Cholestasis Drug misuse Other |

| Intrapartum | Asphyxia Trauma |

| Trauma | External Iatrogenic |

| Unclassified | No cause evident No information |

a < 10th customized weight for gestational age centile.

b If severe enough to be considered relevant.

c Histological diagnosis.

Isoimmunization was previously a common cause of stillbirth with severe fetal anaemia but the introduction of anti-Rh(D) gammaglobulin prophylaxis in 1971 steadily reduced the number of women with anti-red cell antibodies. For those that do have isoimmunization, intrauterine treatments have reduced the chance of affected pregnancies ending in fetal death.

Before 1970, babies with severe congenital abnormalities also formed a much larger proportion of stillbirths. With the advent and steady improvement of prenatal ultrasound, more of these are diagnosed between 12 and 20 weeks’ gestation (Table 48.4). Many women choose termination of pregnancy when faced with such a diagnosis, which subsequently reduces the numbers that end as late fetal death or neonatal death; this represents a change in the statistic, but not the sense of loss for the mother. The widespread use of folic acid supplementation has also reduced the number of pregnancies affected by neural tube defects.

Table 48.4

Examples of lethal or potentially lethal congenital malformations by system

| System | Examples | Diagnostic test |

| CNS | Anencephaly | Early ultrasound scana |

| Cardiovascular | Single ventricle, hypoplastic left heart | Late ultrasound scana |

| Renal | Renal agenesis, urethral atresia | Late ultrasound scan |

| Gastrointestinal | Diaphragmatic hernia, exomphalos | Late ultrasound scan |

| Chromosomal | Edwards syndrome (47 + 18) Patau syndrome (47 + 13) |

Early combined serum/ultrasound screening or later 20-week ultrasound, prompting invasive diagnostic testing |

| Musculoskeletal | Thanatophoric dysplasia, achondrogenesis Some types of osteogenesis imperfecta |

Late ultrasound scan |

a Early usually means 12 weeks’ gestation; late usually means 20 weeks’ gestation.

Stillbirth

Clinical aspects of stillbirth care

Presentation

Most women attend with reduced or absent fetal movement, bleeding or pain, but for some the absence of heart activity is an unanticipated finding at a routine antenatal clinic or midwife visit. Fetal death may be diagnosed during labour or even at the moment of birth.

Diagnosis of death

Auscultation and electronic fetal heart rate monitoring (cardiotocography) can give false reassurance that all is well. If fetal death is suspected, best practice is for an ultrasound scan to be performed by an experienced sonographer. However much suspicion of intrauterine death there had been, the realization that all hope is lost is often met with extreme anguish. It would be futile to pretend that this can be averted and it is appropriate to allow the mother (and her partner) to control the pace of subsequent events. This might include time spent alone with her family to express their grief in private, provided there is no medical emergency for the mother. Any temptation to initiate a long discussion on further management should be resisted until the mother herself is ready.

Immediate management of fetal death

The first medical priority has to be assessment for underlying acute conditions that might threaten the mother’s well-being, e.g. sepsis, pre-eclampsia, occult haemorrhage. This must include physical examination and laboratory testing. If the mother is willing, a second ultrasound scan can be used to assess the liquor volume, placental position if there has been bleeding, and appearances suggestive of concealed abruption. If severe hydrops fetalis is seen, the mother can be prepared for the appearance of her baby. It is also important to test for blood clotting abnormalities (disseminated intravascular coagulation, DIC) that can be triggered when the fetus has been dead for 1 week or more. The result of a Kleihauer test should be obtained urgently for those women who are Rh(D) negative, so as to identify any large fetomaternal haemorrhage. Any transplacental bleed may have occurred a few days before and the window of opportunity for giving anti-Rh(D) gammaglobulin to protect against isoimmunization can be very narrow.

Labour and delivery

Currently, most women undergo vaginal birth, usually through induction of labour, but all the clinical features should be taken into account when coming to a joint decision about the timing and mode of delivery. Some women express a strong desire for caesarean birth. Such requests should be considered respectfully but with advantages and disadvantages being carefully discussed and explored.

Whatever is chosen, some women wish to spend some time at home before any intervention – a time to gather thoughts and to make practical arrangements. The mother should be advised that it is not uncommon to feel spurious fetal movement. If she has any doubt about the diagnosis, a further scan should be offered.

Many maternity units have special delivery rooms for women with an intrauterine death, which are more comfortably furnished but are designed such that the safety of the mother is not compromised by lack of immediate access to emergency equipment. A large proportion of women who have experienced a stillbirth describe their experience of labour as insufferably hard physically. Experienced supportive midwifery care is vital, therefore, together with all appropriate analgesia, though epidural anaesthesia might be precluded, if there is evidence of sepsis or DIC. In general, it is preferable to delay membrane rupture as long as reasonably possible, as the risk of chorioamnionitis might be increased in comparison to live births. There is no known value from the routine use of antibiotics in these situations.

Investigation of the death

Tests that seek to identify the reason behind the death should be recommended for all parents. This is partly to provide the parents with an explanation for the death, but it is also intended to inform prognosis and to help plan any future births. It is important to recognize that the finding of an abnormality is not necessarily the explanation of the death and interpretation of results in the light of the clinical findings is important.

These investigations can include maternal blood tests, bacteriology samples, fetal and/or placental karyotype, and post-mortem examinations (Tables 48.5 and 48.6). Post-mortem examination of the baby includes weight and length, external examination with clinical photography, skeletal radiography and placental histopathology, in addition to conventional autopsy including the placenta. There is the option of a more limited autopsy, excluding certain organs at the parents’ request.

Table 48.5

Maternal investigations recommended for women with late fetal death

| Test | Reason(s) for test | Additional comments |

| Maternal standard haematology and biochemistry including CRP and bile salts | Pre-eclampsia and its complications Multi-organ failure in sepsis or haemorrhage Obstetric cholestasis |

Platelet count to test for occult DIC (repeat twice weekly if conservative management of stillbirth chosen by mother) |

| Maternal coagulation times and plasma fibrinogen | DIC | Not a test for cause of late intrauterine fetal death Maternal sepsis, placental abruption and pre-eclampsia increase probability of DIC Especially important if the woman wishes regional anaesthesia |

| Kleihauer test | Lethal fetomaternal haemorrhage Decide level of requirement for anti-Rh(D) gammaglobulin |

Fetomaternal haemorrhage is a cause of fetal death Kleihauer should be recommended for all women, not solely those who are Rh(D) negative (ensure lab aware if Rh(D) positive) Tests should be undertaken before birth as red cells might clear quickly from maternal circulation In Rh(D) negative women, a second Kleihauer test also determines whether sufficient anti-Rh(D) has been given. |

| Maternal bacteriology (blood and cultures, vaginal and cervical swabs) | Suspected maternal bacterial infection including Listeria monocytogenes and Chlamydia spp | Indicated in the presence of maternal pyrexia, flu-like symptoms, offensive or discoloured liquor |

| Maternal serology | Occult maternal–fetal infection | Stored serum from booking tests can provide baseline serologyErythrovirus (Parvovirus B19), rubella (if non-immune at booking), CMV, herpes simplex and Toxoplasma gondii |

| Maternal random blood glucose, HbA1c, thyroid function | Occult maternal endocrine disease | Women with gestational diabetes mellitus return to normal glucose tolerance within a few hours after late intrauterine fetal death has occurred |

| Anti-red cell antibody serology | Immune haemolytic disease | Indicated if: fetal hydrops evident on ultrasound, at delivery or on post-mortem |

| Parental bloods for karyotype | Parental balanced translocation Parental mosaicism |

Indicated if: aneuploidy in fetus or failed fetal testing |

Table 48.6

Fetal investigations recommended for late fetal death

| Test | Reason(s) for test | Additional comments |

| Fetal and placental microbiology | Fetal infections | Swabs from maternal and fetal surfaces of the placenta, swab from surface of fetus |

| Fetal and placental tissues for karyotype (and possible single gene testing) | Aneuploidy Genetic sexing Single gene disorders |

Absolutely contraindicated if: parents do not wish (written consent essential) |

| Post-mortem examination External Autopsy Microscopy X-ray |

Absolutely contraindicated if: parents do not wish (written consent essential) External examination should include weight and length measurements Perinatal pathologist or neonatologist can examine for dysmorphic features if parents do not want autopsy |

Autopsy can provide key information that is not gained in any other way, but the intrinsic nature of the procedure poses great emotional difficulties for some parents. A simple explanation of the nature of autopsy and its benefits should be offered to all parents, together with a leaflet and an assurance that the baby will be handled in a dignified manner, but attempts at persuasion must be avoided.

Cultural and legal aspects of stillbirth

After the birth, parents often spend time with and caring for their baby. This is extremely important for many couples but it is not for all. There is some evidence to suggest that seeing the baby can adversely affect the emotional recovery and so the views of parents should be respected. Naming the child is also an important step for many parents. If there is any doubt about the sex of the baby when choosing a name, this can often be resolved within 2 days, using Quantitative Fluorescent PCR (QF-PCR). Some parents find it comforting to have photographs of the baby, together with handprints, footprints and a lock of the baby’s hair. Some will wish to leave a toy, family photographs or a letter in the coffin to be with the baby. Many parents find these acts of care comforting, but they are not for every family.

Legal matters

There is no requirement to discuss the death with HM Coroner or the Procurator Fiscal simply because it is unexplained. Only if the fetal death resulted from a criminal act such as a deliberate stabbing, should these legal officers be informed. There is a legal requirement for doctors to certify the stillbirth and for parents (or a nominated representative) to notify the birth with the Registrar of Births. Most hospitals have a bereavement officer, whose role it is to explain and support certification, registration and to discuss funeral arrangements.

Continuing emotional support

An empathetic approach is essential and an ability to understand and anticipate the range of emotions and needs of the women and their companions. For more skilled emotional support, most units have trained counsellors who will follow-up the parents in the community. It is essential that the general practitioner and community midwife be informed before the woman is discharged from hospital, so that everyone is fully aware of the situation and they can play their part in continuing care. The couple should also be offered a booklet containing information on local support groups, for example SANDS – Stillbirth & Neonatal Death Society. If there is any suspicion of serious mental ill-health following stillbirth, expert psychiatric advice must be sought urgently.

Neonatal mortality

Neonatal mortality is the loss of a live-born baby within the first 28 days of life. In contrast to the parents of stillborn children, the parents will have seen and usually have held their child while alive but usually in circumstances in which the baby is struggling to survive, often in neonatal intensive care.

Legal aspects of neonatal death

In contrast to stillbirths, deaths that occur in the neonatal period for which the cause of death is unknown, suspicious or related to suboptimal care should be reported to HM Coroner or the Procurator Fiscal.

Causes and prevention of neonatal death in countries with advanced health care

Associated factors and diseases

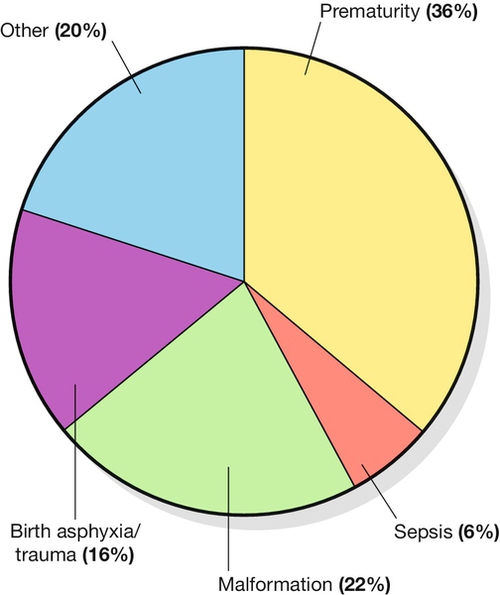

These are outlined in Figure 48.2 (derived from Child Health Epidemiology Reference Group of WHO and UNICEF, 2008). Although only about 8% of babies are born pre-term, prematurity is associated with almost 80% of perinatal deaths in the UK, the majority of which occur during the early neonatal period. Most pre-term births relate to spontaneous labour, which itself might be precipitated by bleeding or infection, but a significant minority of pre-term deliveries are initiated by obstetricians because of serious maternal conditions (e.g. haemorrhage, pre-eclampsia) or fetal disease (e.g. growth restriction, malformation, isoimmunization or twin-to-twin transfusion syndrome). The direct causes of death among babies born pre-term are varied, but for the majority, it is the result of sepsis and/or respiratory failure secondary to respiratory distress syndrome (hyaline membrane disease).

Preventing pre-term birth

Interventions to prevent pre-term birth have been a goal for maternity specialists for more than four decades, with little success. Of concern, pre-term delivery rates appear to be rising in the UK and this is thought to be linked to lifestyle issues: smoking, illicit drug use, obesity and dietary habits. One lifestyle change programme to prevent pre-term birth is smoking cessation. Medical interventions, including cervical cerclage (a stitch to keep the cervix closed) and tocolysis (drugs to stop uterine contractions) generate only small benefits.

Reducing the consequences of prematurity

In contrast to attempts to prevent pre-term birth, advances in perinatal care have improved the survival rates and quality of survival for many premature infants. Antenatal interventions administered to women at imminent risk of pre-term delivery that improve outcomes include maternal corticosteroids (reduce incidence of neonatal lung complications), magnesium infusion (neuroprotection, reduces incidence of cerebral palsy) and intrapartum antibacterial prophylaxis (reduces the incidence of early onset sepsis from Group B Streptococcus). Improved neonatal care includes the development of improved techniques for respiratory support, exogenous surfactant administration, and more sophisticated feeding schedules. Survival rates have improved over time but survival rates below 26 weeks’ gestation remain low (Table 48.7).

Table 48.7

Neonatal survival rates in countries with advanced health provision, according to gestation

| Gestational age | Neonatal survival rate (/1000 live births) |

| 22 weeks | 2% |

| 24 weeks | 40% |

| 26 weeks | 77% |

| 28 weeks | 92% |

| 32 weeks | 98% |

| 36 weeks | 99% |

| Term | 99.8% |

Data for < 28 weeks taken from UK EPICURE 2 study (2012).

Medical follow-up of perinatal loss

Follow-up appointment

A meeting to explain and discuss the results of tests and their implications should be arranged at a time to suit the parents. The appointment is usually about 6 weeks after delivery when test results are available, but flexibility is important if parents want to meet earlier or later than this. The location needs to accommodate the needs of the parents and the doctor. An office location has the advantage of allowing flexibility in terms of duration of the meeting. Some doctors are able to offer home visits if parents find it very difficult to return to the unit where their baby was stillborn. All test results should be at hand, and knowing the name and sex of the child before the meeting is important, if possible. It can be helpful to explain the purpose of the appointment and that there is usually no need for a physical examination. A letter should follow summarizing all results and issues discussed, tentative plans for future pregnancy and encouraging open access for further questions.

Unsurprisingly, the meeting can be very difficult for parents, partly because of remembrance of the time in the hospital, and particularly when there have or may have been medical errors. The telling of their story is also a key component of the meeting for many parents, and this can help identify questions they wish to be answered.

Pregnancy after stillbirth

Future pregnancy

There seems to be no clear benefit of advising a particular duration of time before a subsequent pregnancy but ideally, the woman will be emotionally ready and also physically prepared for pregnancy in terms of lifestyle so as to optimize outcomes. Medical care in the next pregnancy will be guided by the nature and cause of the previous loss, but also by the needs and wishes of the mother. Throughout, it is important to offer easy access to professional advice and support, especially so at times of heightened anxiety such as the gestation of the previous stillbirth. There should be an easy point of contact at any time if problems do occur.

The likelihood of late fetal death in a subsequent pregnancy after an unexplained stillbirth is < 5%, but anxiety will persist for most parents, despite the high chance of a positive outcome. In the absence of any identifiable cause, it is impossible to monitor for specific problems, and that brings uncertainty with it. Screening for congenital problems may provide some reassurance, but it is likely that all such tests were normal with the pregnancy that resulted in stillbirth. More frequent antenatal visits may also provide an opportunity for support, particularly with growth and well-being scans, every few weeks from 24 weeks onwards. The woman’s carers should not expect to allay her anxieties but to support her through to the time of birth. By about 38 weeks, many women become increasingly anxious, and are often keen to have labour induced, or caesarean section arranged. Such requests should be viewed sympathetically, since the prospect of a second late intrauterine fetal death, albeit remote, may be unbearable.

Learning from adverse events

It is an ethical and statutory duty of all healthcare organizations to learn from adverse events. Maternity and neonatal care has a long history of self-reflection, as exemplified by the National Confidential Enquiries Into Maternal and Perinatal Deaths. Risk management organizations in the UK require that all perinatal deaths are incident reported and locally investigated to identify lessons that can be learned to improve care. A National Confidential Enquiry into stillbirths in the early 21st century considered half to be associated with suboptimal care. Most maternity units hold quarterly perinatal mortality meetings for case discussions. They are intended for all health professionals involved in perinatal care, including perinatal pathologists, and they allow a multidisciplinary approach to the case review. In addition to striving for an accurate diagnosis, the team also seeks to define ways in which such a death might be prevented in the future. Provided this learning process is conducted in a non-judgemental atmosphere, it can be a useful learning exercise for all concerned.

A global perspective of perinatal death

The broad picture

As with maternal mortality, reduction in child mortality has been highlighted as one of the Millennium Development Goals of 2000 (MDG-4). The millennium project is aimed at all children under 5 years, of whom 10 million die each year, 80% before their first birthday; 40% in the first 4 weeks. The proportion of neonatal deaths is rising with 450 every hour from preventable causes. There are fewer stillbirths worldwide, but nevertheless 3 million babies are stillborn every year. With the 3 million who die in the first week of life, and the further 1 million who die before they are 4 weeks old, that means 7 million perinatal deaths occur each year.

The World Health Organization (WHO) estimates that 98% of perinatal deaths occur in under-resourced countries and 49% occur in just five countries: Nigeria, India, China, Pakistan and the Democratic Republic of the Congo. The highest rates of perinatal mortality are found in Africa, at 62/1000 births; nearly 2 million perinatal deaths a year. The worst affected parts of the continent are middle and west Africa, where perinatal mortality rates in some countries are so high that over 1 in 10 babies are either stillborn or die within the first week of life. Although the rate of perinatal mortality in Asia is lower, at 50/1000 total births, the much higher population there means that its overall burden of perinatal deaths is far higher than that of Africa, with over 4 million deaths each year.

Stillbirths

Of the stillborn babies, one-third of deaths are probably due to intrapartum events and are potentially avoidable if prompt, good-quality maternity care was available. It should be a matter of great concern that half of the world’s women give birth in their own home with no skilled birth attendant. Currently, training courses are being evaluated to increase the skills of birth attendants, whether from traditional professions or not.

Neonatal mortality

Globally, the main direct causes of neonatal death are estimated to be complications of pre-term birth (29%), severe infections (28%), birth asphyxia and trauma (21%) and malformations (7%) (WHO and UNICEF statistics 2008). Determining why newborns die in developing countries is difficult because most deaths occur at home, and families are often reluctant to seek outside help for a variety of cultural, logistical and economic reasons. The data available identifies four main causes of neonatal death in Africa, the frequency order being:

1. infection – largely bacterial sepsis, diarrhoea and tetanus

2. complications during delivery (leading to birth asphyxia and birth injuries)

3. complications of prematurity

4. congenital anomalies.

Undernutrition is thought to be an underlying factor in more than two-thirds of these deaths.

Infections

Every year, an estimated 30 million newborns acquire a neonatal infection, and 1–2 million of these babies die. The most common of these infections are early neonatal septicaemia, later neonatal pneumonia, diarrhoea and neonatal tetanus, which together account for around 30% of neonatal deaths. Exclusive breastfeeding helps to prevent many infections in the first month of life. Simple hygiene measures and clean water supply are also important components of the prevention of infection.

Neonatal tetanus prevention programmes have been a particular success; it has been eliminated in over 100 countries through immunizing mothers with tetanus toxoid, ensuring hygienic delivery practices and maintaining clean care of the umbilical cord stump. Tetanus toxoid is one of the cheapest, safest and most effective vaccines, and it costs less than US$1.50 – a sum that covers production and delivery costs of three doses of vaccine. A completed course ensures immunity for a newborn during the critical first 2 months of life. Success is not complete, however, with a substantial minority of pregnant women in developing countries still not being fully immunized.

Complications during delivery

WHO estimates show that between 4 and 9 million newborns suffer severe birth asphyxia or trauma each year. Of these, an estimated 1.2 million die and at least the same number develop severe consequences such as cerebral palsy and mental impairment; disabilities that impinge on already scarce resources for poor families.

Birth attendants must be skilled enough to be able to manage normal deliveries avoiding unnecessary interventions, and diagnose and manage or refer women with complications when possible. It is believed that a skilled health worker is in attendance for just half of all births, and in some countries, the rate is very much lower; approximately 53 million women give birth each year without the help of a trained attendant.

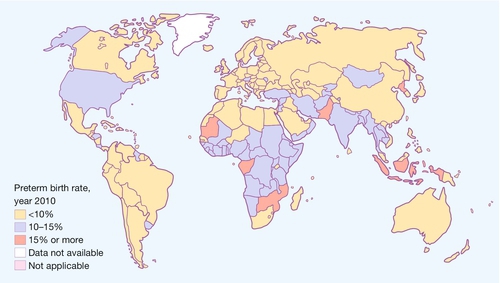

Prematurity

Although pre-term birth is less important proportionately than in developed countries, globally there are 15 million every year and the figure is rising. The frequency for the 184 individual countries ranges from 5% to 18% (Fig. 48.3). More than 60% of these pre-term births occur in southern African and south Asia. Just over 1 million babies born prematurely will die as a result of complications of the birth itself or of prematurity. It has been estimated that 75% of neonatal deaths related to prematurity could be prevented with simple measures.

Congenital anomalies and diseases

Together, these constitute the fourth most common cause of newborn deaths worldwide. The category includes neural tube defects, severe hypothyroidism and congenital rubella syndrome, all of which can be largely prevented with low-cost interventions, respectively folic acid, iodinated salt and rubella immunization.

Low-cost interventions for resource-poor countries

Interventions to reduce the number of these losses significantly need not be complicated. In a rural part of India, where basic neonatal resuscitation techniques were taught to traditional birth attendants, the recorded stillbirth rate decreased from 18.6% to 9% over a 3-year period. Recent reviews indicate that essential care during pregnancy, childbirth and the newborn period costs an estimated US$2100 for each life saved, just US$3 a year per capita in low-income countries. A list of such interventions is listed in Box 48.1. The total cost of low-cost perinatal interventions for the 75 countries with the highest neonatal mortality rates would cost a modest US$4.1bn (2010 estimates).

Conclusions

Death of a baby before or shortly after birth is a personal tragedy, which is lived out on a global scale. While there are many differences between countries in terms of the size and nature of the problem, there are many common lessons on prevention and care for affected families that can be shared across borders. Improving maternal health and education, preventing pre-term birth, improving hygiene and ensuring skilled birth attendants are challenges that face us all.