CHAPTER 1 What Is a Simulator–a Clinical Checklist or a Theater?

No one’s hand goes up. There weren’t any hands free; they were all glued to their keyboards!

Click, click, click, click, click, click.

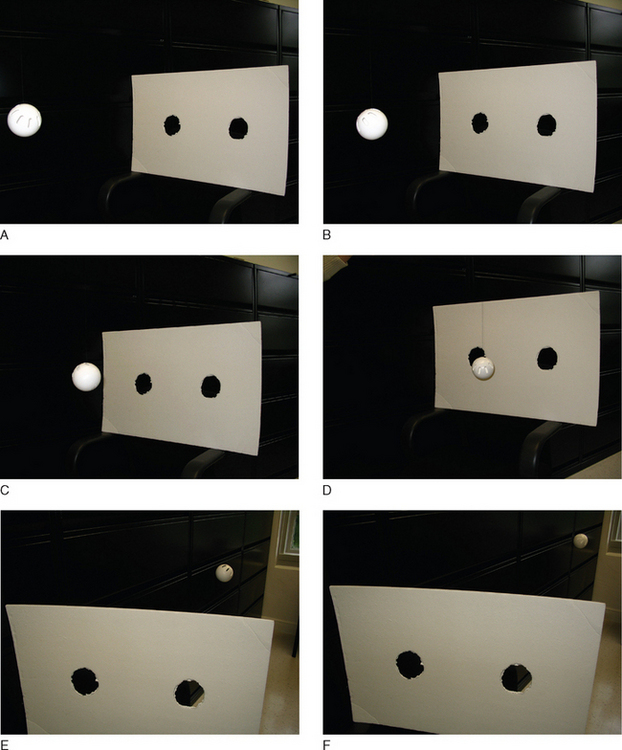

“Simple,” James explains, “the single, indivisible electron passes through both holes.”

Click, click, click… click. Click, click. Click. Click.

The single electron passes through both holes.

Now just how the heck can it do that?

No. As the core of this book—the 50 simulator scenarios—show, each scenario has an element of the clinical checklist, and an element of theater—educational theater.

For example, you set up a simple scenario for medical students:

Good lessons all, and good lessons linked to the “simulator as a clinical checklist.”

But the good thing about the simulator, and what really gives it a zing from the instructor’s and the student’s point of view is that the simulator also functions as “educational theater.” And theater is limited only by the imagination of the playwright and the actors. So you can end up with Juliet lamenting her romantic plight, Willie Lomax lamenting his wasted life, or Stella lamenting that she has “always depended on the kindness of strangers.”

Inducing General Anesthesia in a Routine Patient: Theater

Clinical Checklist

From a lot of angles, the Simulator as “clinical checklist teacher” has appeal.

“Damn, I wish I’d done more training in that Simulator!”

Simulators find their biggest champions in the world of Anesthesia. No surprise, then, that anesthesia people have done the initial research on “Simulator as Clinical Checklist Teacher.”

“At this point, no one was sure whom to call.”

“Internal Medicine thought they were running the code but forgot to check with the ICU staff.”

“Upon review, no one was sure who ordered the fatal dose of….”

“By failing to check the chart, no one realized that….”

“Protocol required that … but what ended up happening was….”

Behavioral learning is a real eye-opener. Medicine can be pretty cut-and-dried.