CHAPTER 4 Working on Communication Skills in the Simulator

Picture yourself sitting in front of a person with a doctorate in education (EdD) from Harvard. This professor now holds joint appointments at MIT and Harvard.

You ask a question about the behavioral aspects of Simulation training.

“Well”, the professor with ties to MIT and Harvard says, “you have to read.”

And the professor looks at you.

Who are we to argue with that?

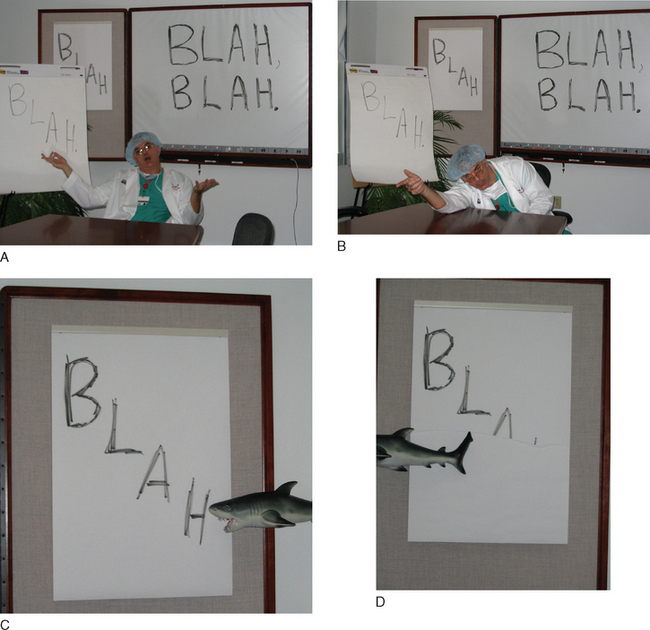

An initial reaction might be, “Ah, to hell with that psycho-babble. I’m training people in the clinical arena! Codes! Shock! STAT! That’s the ticket. The Simulator was never meant to be a marijuana-laced, Haight-Ashbury-esque, harmonic convergence love fest. Nor is the Simulator meant to teach us how to talk ‘administrative-ese’ like a bunch of CPAs. So let’s skip the ‘getting in touch with our feelings’ and the ‘prioritization of goal-oriented intermediary assessment protocols.’ That’s all sissy stuff.”

CRISIS RESOURCE MANAGEMENT

Crisis is a can of Coke that you shake up, then pop open all at once.

Management is a can of Coke you left sitting open in the fridge for 3 days.

Conceptualizing

The Professor was right: “You have to read.”

Hmm. Where to now? Here are the questions:

Here is the answer to the first question: What should I read?

Here is an answer to the second question, “How do I make this reading ‘meaty’?”

COMMUNICATION AND BEHAVIORAL STUFF WRIT GRITTY FOR MEDICAL FOLK

Learning

“The first stage of contact with any new material … must inevitably be of the trial and error sort.”

Bingo! Go into the Simulator, try to intubate a swollen airway, change the head position, try a different blade…. No go? Eventually you “trial and error” your way all the way to a surgical airway, placing a catheter into the Simulator’s cricothyroid membrane and starting jet ventilation.

Dewey said, “What is [needed is] an actual empirical situation as the initiating phase of thought.”

That’s a 4+ empirical situation for learning.

“Oh man! I’m thinking vagal, then V tach!”

“Did you catch the temp rising?”

“How come you got the tube in—his mouth was like a rock!”

Compare that with your average “regular” lesson, a lecture.

The more you read Dewey, the more you love the Simulator.

You remember your “Hillary’s Step” lessons. You tend to forget your “Borders” lessons.

How About Medical Education?

“Hang around long enough, and you’ll see what you need to see,” goes the traditional thinking.

Enter the Simulator

And when you look at it from another angle, it makes sense that we practice on un-killable Simulators. With a Simulator, we are doing our first learning on a pretend person. We are doing our first drive in a pretend car, our first flight in a pretend plane.

Errors

(Or better yet, just sit back and enjoy. These stories rock!)

So put on your “medical education” cap and follow along. The questions you ask yourself are:

If you’re not in the learning mode but are just in this for voyeuristic thrills, ask yourself:

Show Me the Money

Now go to the three questions.

At the foundry, the floor workers had to do a Simulation where they designed more efficient molds. Voila! They generated less scrap, saved money, and took this lesson back to the factory. And now the foundry is in the black. Uh, as in black ink, not black soot.

Well hot diggity dog, the Simulator did come to the rescue!

Could a Medical Simulator work similar magic?

A Samovar with Attitude

How Did this Error “Evolve”?

How Could Such an Error Evolve in Medicine?

Charge of the Light Brigade

Now we shift gears a little and look at errors in military history.

“Attack what? What guns, Sir?”

Half a league, half a league, half a league onwards,

All in the valley of death rode the six hundred.

Cannon to the front of them volley’d and thunder’d.

The Chernobyl paradigm cranked the whole subject up a notch. Error analysis takes on genuine palpable significance as a 9 foot thick chunk of burning, radioactive concrete falls on your head.

How Did this Error “Evolve”?

So everybody hated everybody, and no one knew anything.

So, at this point, the entire “Command and Control” is in place for a complete fiasco.

Then, the following communications occurred.

And die they did: 607 rode down into the valley, 346 rode out.

How Could such an Error Evolve in Medicine?

How Could a Simulator Help Here?

Yapping

Well, in medical circles, sometimes talking the talk is walking the walk.

You’re the doc, you have to now talk the talk.

However it’s done, it’s worth learning to talk the talk.

This superb teaching vehicle has developed a mnemonic, CONES, for “have to tell” situations.

This might look neat and tidy, but no rugged explanation fits into neat pigeonholes. Emotion pokes its head into every phase of the conversation. (Wouldn’t you get emotional if you were getting bad news?)

If you don’t belong to that list, read on.

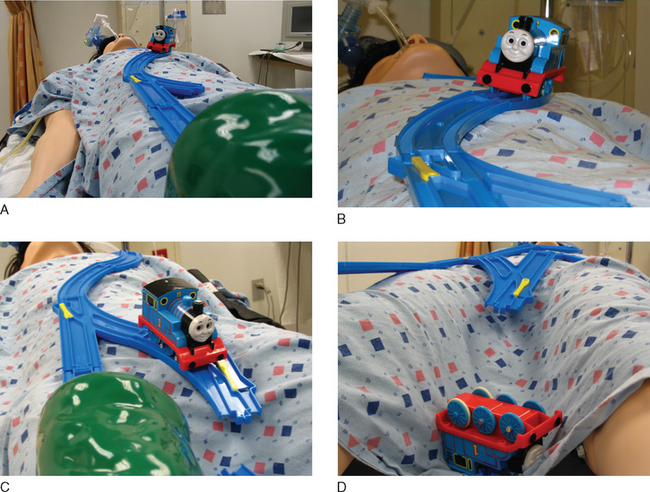

Any doctor in clinical practice has had a few train crashes, just as Thomas the Train jumps the tracks in Figure 4-5. Let’s read about a case where the Thomas the Train crash involved a finger.

First, How to Do It Wrong: A Lost Finger

His right index finger got squished and amputated.

“What happened?” Mr. O’Shaughnessy asked the floor nurse.

The floor nurse didn’t know, he had just come on shift. Maybe the nurse from the last shift knew.

Let’s Take a Different Tack, the CONES Approach

“We’re here to talk to you today about what happened to your hand.”

Acknowledge the anger the patient must feel. (Think how you would feel if this had happened to you.)

A cardboard cutout patient, not a real one.

Here goes the same episode with more realistic patient reactions.

“God damn, it’s about time you got in here,” Mr. O’Shaughnessy says.

“We’re here to talk to you today about what happened to your hand.”

Then the anesthesiologist takes up the thread: “Part of the operation is putting the foot of the bed down, then at the end we put the foot of the bed up. There’s an elbow there, and when that elbow folded up your finger got pinched in there and was cut off. At the time, I was watching your vital signs and breathing, and I didn’t check under the blankets, where your finger was getting hurt.”

“Easy for you to say it’s a shock, I’m the guy who looks like a freak now,” Mr. O’Shaughnessy says.

Acknowledge the anger the patient must feel. (Think how you would feel if this had happened to you.)

Negotiating

Chernobyl was a samovar with attitude.

Negotiating is yapping with attitude.

An Intensive Care Unit Anywhere in the US of A

Anesthesiologist: “No, YOU go to hell!”

Applied to this mini-conversation, then, the Difficult Conversations approach might look like this.

The Case in Point

From day 1, these two specialists have gone at it hammer and tongs. The surgeon wanted a thoracic epidural to help with pain control, but the anesthesiologist didn’t want to place one for fear of some bleeding into the epidural space. “Humph,” the surgeon says, “if the anesthesiologist had a little guts, that epidural would have helped with pain control, McGillicutty would be able to take bigger breaths, and we wouldn’t be in this fix now!”

And now things have come to a head in, of all places, the tippy toes.

They meet in the hallway and exchange views, leading to the (now famous) discussion.

For argument’s sake, my negotiating angle is from the point of the view of the anesthesiologist.

Difficult Conversations maintains that most arguments are not about getting the facts right. Rather, most arguments are “not about what is true, they are about what is important” (p. 10).

The devil’s not as black as he’s painted when you sit down and talk with him.

No allegiance to surgery. No allegiance to anesthesia.

Just—what’s wrong with Hiram, what can we fix, what can’t we fix?

Look over the chart, do a physical exam, start from ground zero.

Would such a “start from the very beginning” approach argue for the Podiatry consult, yes or no?

Podiatry consult—what will it cost? Will it really help anything?

We helped get Hiram better. And in the future, we’ll work even better together!

And now to let you in on a little secret.

“He may be dirty out there, but now he’s our responsibility. Make him neat as a pin.”

Living

This is the last of the “Behavioral Stuff Writ Gritty for Medical Folk.”

Put into a medical professional’s life, Covey’s seven habits could look like this:

Rein it in! Debrief time is not lecture time!

To make a true “Aha” moment, you need to dig into what they understand, what their point of view is, before you “solve it for them.”

By first understanding, you lay the groundwork to be understood.

This may sound like some semantic trickery, but it’s actually the way to go.