CHAPTER 64 Wear and Elbow Replacement

INTRODUCTION

Over the past decade, the reliability and success of total elbow replacement surgery has become more established. The durability of total elbow arthroplasty (TEA) for rheumatoid arthritis is now similar to that of hip replacement.2 Indications have also expanded to include the full spectrum of traumatic conditions: distal humeral nonunion,9 instability,10 ankylosis,7 established arthritis,11 and acute intra-articular, comminuted fractures in selected older patients.4,5

Until recently, wear of the polyethylene articulating surface had not been recognized as a problem or addressed in the literature. Although this may not be a practical concern in unconstrained and unlinked designs, wear of the articular polyethylene bushings in linked, semiconstrained designs is a potential issue, particularly with the evidence of the increasing longevity and improved function that these designs now have, resulting in increased use of the limb. Until recently, this specific topic has not been considered when complications with TEA are being discussed.3 This chapter focuses on our experience with the problem as the development requires or implies long-term stable fixation. Hence, there has been little in the literature regarding this problem with other designs.

To address this issue, we reviewed the Mayo Clinic experience with reoperations to exchange worn bushings in the linked, semiconstrained Coonrad-Morrey TEA. Twelve of 919 TEAs reviewed (1.3%) had undergone isolated bushing exchange for wear.6 An additional six patients were diagnosed as having bushing wear on the basis of an asymmetric anteroposterior orientation of the ulnar component within the humeral yoke, although these patients did not have a revision.

CLINICAL AND RADIOLOGIC FEATURES

Pain, crepitus and squeaking sounds are the most common presenting features of articular bushing wear. Loss of range of motion is not marked, and there are no symptoms of functional instability or weakness. In our experience, the patients with post-traumatic arthritis had a higher prevalence of bushing wear (seven of 294; 2.4%) than did those with rheumatoid arthritis (five of 377; 1.4%).6

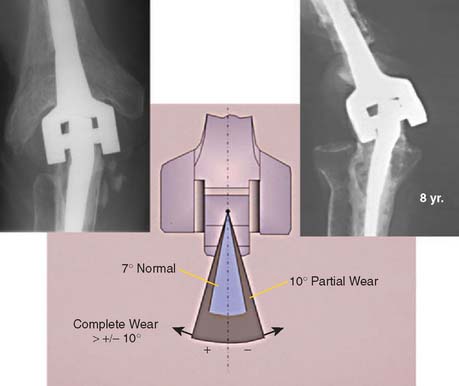

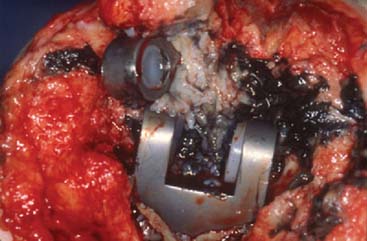

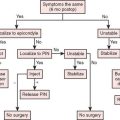

Radiographic assessment is conducted before the total elbow replacement to identify deformity and after replacement to identify signs of bushing wear, osteolysis and status of the implant. The criteria for the assessment of wear were described by Ramsey et al.10 Anteroposterior plain radiographs of the elbow in full extension made following the index arthroplasty and at the time of bushing exchange are compared. The prosthesis was designed with 7 to 10 degrees of varus-valgus laxity. A line is drawn parallel to the yoke of the humeral component, and another line is drawn parallel to the medial or lateral surface of the articular surface of the ulnar component. An angle of intersection of more than 7 degrees between these two lines indicates alteration of the bushing due to wear or plastic deformation. An angle of more than 10 degrees is considered to indicate mild to moderate bushing wear (Fig. 64-1). Of importance is that none of our patients experienced loosening of the implant because of wear. It must be emphasized the extensive osteolysis seen in the past around the ulnar component was related to osteolysis caused by loosening of a “precoat” ulnar surfaced component. These devices were implanted between 1994 and 2000. Some have confused this appearance as being caused by wear. As in the hip the proper interpretation is the implant becomes loose and the particulars associated with this are termed accelerated bushing wear (Fig. 64-2). Typically bushing wear, even when excessive, causes local osteolysis, but not implant loosening (Fig. 64-3).

SURGICAL TECHNIQUE

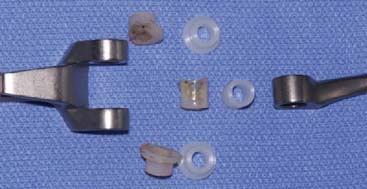

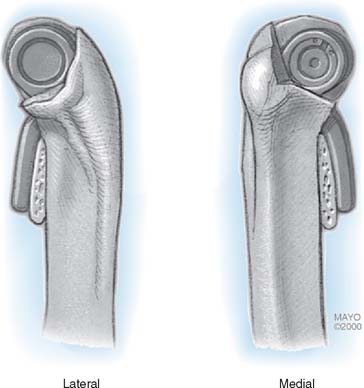

The treatment of symptomatic wear is simply to exchange the worn articular bushings. The previous skin incision is used to explore the elbow, and the ulnar nerve is palpated. If the patient has ulnar nerve symptoms, the nerve is explored and decompressed. If the nerve is not symptomatic, it is identified proximally at the medial aspect of the triceps and is protected throughout the procedure. If the distal part of the humerus has been resected or is absent, the triceps is left attached to the ulna, the pseudocapsule is entered medially and laterally, the articulation is disengaged, and the humerus and ulna are separated. If the condyles are intact, the triceps is again reflected from the ulna according to a previously described technique. At this juncture, the anterior aspects of the medial and lateral epicondyles are removed to an extent sufficient to allow the implant locking pin to be removed both medially and laterally (Fig. 64-4). The posterior aspects of the condyles are left intact. The medial and lateral bushings are removed from the humerus, and the bushing is removed from the ulna. The soft tissue is assessed, and a thorough débridement is carried out. If the wear is sufficient to have resulted in impingement of the metallic ulnar component on themetallic humeral component, then black synovitis is the predominant feature (Fig. 64-5).

FIGURE 64-4 The condyles are preserved by removing sufficient anterior condylar bone to expose and remove the pin.

(With permission, Mayo Foundation.)

After débridement, the implant is inspected for the integrity of the fixation and orientation to determine if revision of either implant is necessary. If there has been resorption or osteolysis at the distal aspect of the humerus or the proximal aspect of the ulna, the interface is thoroughly cleaned and is filled with polymethyl methacrylate. Fresh bushings are then inserted in the ulnar and humeral components, and the implant is coupled with the use of the pin-within-pin snap-fit articulation (Fig. 64-6). If the preoperative assessment and intraoperative evaluation indicated a fixed angular deformity that cannot be corrected passively, then the soft tissue is released to allow correction of the deformity. Thus, an extensive flexor release from the humerus is carried out for the treatment of varus deformity. Similarly, an aggressive extensor tendon release, including the distal fibers of the brachioradialis, is performed to treat a fixed valgus deformity. The triceps is reattached with use of a cruciate and transverse drill pattern, as previously described.1

RESULTS

Radiographic assessment before index TEA in this group revealed a markedly distorted joint in nine patients, with severe rheumatoid arthritis in four, marked varus or valgus deformity of more than 10 degrees in nine, and gross dissociation (a flail elbow with loss of the distal humeral condyles) in four (Fig. 64-7). Nine of the elbows had absence of one or both distal humeral condyles.

All 12 patients had an excellent or good result immediately following the index arthroplasty. Postoperative anteroposterior radiographs revealed the articulation to be at the limits of the designed angular tolerance in nine of the 12 patients, indicating significant stresses at the articulation from severe pre-existing deformity. At the time of bushing exchange surgery, no significant osteolysis or loss of fixation was present (Fig. 64-8).

More recently, Wright and Hastings also documented bushing wear in 10 patients with the TEA of the same design.13 They identified post-traumatic arthritis, supracondylar nonunion, male sex, young age, and high activity level as associated factors. Importantly, these investigators also implicated failure of the “O” ring, which allows the axis pin to back out as an addition factor of accelerated bushing wear. In a series of semiconstrained TEAs for chronic dislocation of the elbow, Mighell et al8 documented one in six required bushing exchange.

Further information is partly limited by the low incidence and by lack of routine stress radiographs to document the absolute wear rate. However, probably the most significant feature with the greatest prognostic importance is the presence of severe preoperative deformity at the time of index elbow replacement. In some cases, the angular deformity may even exceed the tolerance of the design but it is these very problems that can be addressed only by this type of coupled implant.

CONCLUSIONS

Despite the increased longevity of semiconstrained linked total elbow prosthesis and the use of these implants to treat an increasingly complex array of pathologic conditions, the prevalence of articular wear requiring reoperation is very low (1.3% in our experience of such implants inserted over a 20-year period). A higher bushing revision rate is associated with a younger patient with traumatic conditions and long established fixed deformity. The presence of substantial malrotation of components at the time of implantation, even without deformity, can also contribute to increased bushing wear.12

1 Bryan R.S., Morrey B.F. Extensive posterior exposure of the elbow. A triceps-sparing approach. Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res. 1982;166:188.

2 Gill D.R., Morrey B.F. The Coonrad-Morrey total arthroplasty in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. A ten to fifteen-year follow-up study. J. Bone Joint Surg. Am. 1998;80:1327.

3 Gschwend N., Simmen B.R., Matejovsky Z. Late complications in elbow arthroplasty. J. Shoulder Elbow Surg. 1996;5:86.

4 Kamineni S., Morrey B.F. Distal humeral fractures treated with noncustom total elbow replacement. J. Bone Joint Surg. Am. 2004;86:940.

5 Kraay M.J., Figgie M.P., Ingils A.E., Wolfe S.W., Ranawat C.S. Primary semiconstrained total elbow arthroplasty. Survival analysis of 113 consecutive cases. J. Bone Joint Surg. Br. 1994;76:636.

6 Lee B.P., Adams R.A., Morrey B.F. Polyethylene wear after total elbow arthroplasty. J. Bone Joint Surg. Am. 2006;87:1080.

7 Mansat P., Morreym B.F. Semiconstrained total elbow arthroplasty for ankylosed and stiff elbow. J. Bone Joint Surg. Am. 2000;82:1260.

8 Mighell M.A., Dunham R.C., Rommel E.A., Frankle M.A. Primary semiconstrained arthroplasty for chronic fracture-dislocations of the elbow. J. Bone Joint Surg. Br. 2005;87:191.

9 Morrey B.F., Adams R.A. Semiconstrained elbow replacement for distal humeral nonunion. J. Bone Joint Surg. Br. 1995;77:67.

10 Ramsey M.L., Adams R.A., Morrey B.F. Instability of the elbow treated with semiconstrained total elbow arthroplasty. J. Bone Joint Surg. Am. 1999;81:38.

11 Schneeberger A.G., Adams R.A., Morrey B.F. Semiconstrained total elbow replacement for the treatment of posttraumatic osteoarthritis. J. Bone Joint Surg. Am. 1997;79:1211.

12 Schuind F., O’Driscoll S., Korinek S., An K.N., Morrey B.F. Loose-hinge total elbow arthroplasty. An experimental study of the effects of implant alignment on three-dimensional elbow kinematics. J. Arthroplasty. 1995;10:670.

13 Wright T.W., Hastings H. Total elbow arthroplasty failure due to overuse, C-ring failure, and/or bushing wear. J. Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2005;14:65.