Weakness

Perspective

The complaint of weakness is common in emergency department (ED) patients and may be vague, subjective, and difficult to characterize. True loss of strength from a neurologic or muscle fiber lesion must be distinguished from other systemic conditions that result in fatigue, dyspnea, or imbalance because of inadequate substrate delivery to the nervous system or muscle unit. Such conditions may be described as weakness by the patient but are likely caused by cardiovascular, pulmonary, infectious, or metabolic processes. This chapter focuses on the evaluation of acute neuromuscular weakness; it may be focal or generalized and may originate in central or peripheral nerves, the neuromuscular junction (NMJ), or myofibers themselves. Other chapters provide more detail on peripheral nerve (Chapter 107) and neuromuscular disorders (Chapter 108).

Epidemiology

The epidemiology of weakness is closely linked to the epidemiology of other diseases and medical conditions. Although weakness can be a presenting problem at all ages, patients who are elderly or chronically ill are more likely to develop weakness. Advanced diabetes, cardiovascular and pulmonary diseases, chronic infectious diseases, and cancer may produce neuromuscular weakness through secondary effects on the brain and neuromuscular system. Brain, spinal cord, peripheral nerve, and neuromuscular causes of weakness are much less common than weakness that is secondary to other medical conditions.1

Pathophysiology

There are a number of physiologic considerations for the patient with diffuse weakness (Box 13-1).

Conditions that have only peripheral effects at the NMJ and muscle have preserved reflexes.

Differential Considerations

If by history, physical examination, and bedside ancillary testing the patient does not appear to have derangements in intravascular volume or cardiopulmonary function, metabolic abnormalities, or a source of infection, the investigation turns to a neural or primary muscular cause for weakness. Often these patients will have some asymmetrical finding on their neurologic examination. The critical and emergent diagnoses for neuromuscular weakness are listed in Table 13-1.

Table 13-1

Critical and Emergent Causes of Neuromuscular Weakness

| Critical Diagnoses | |

| Cerebral cortex or subcortical | Ischemic or hemorrhagic cerebrovascular accident (CVA) |

| Brainstem | Ischemic or hemorrhagic CVA |

| Spinal cord | Ischemia, compression (disk, abscess, or hematoma) |

| Peripheral nerve | Acute demyelination (Guillain-Barré syndrome) |

| Neuromuscular junction | Myasthenic or cholinergic crisis Botulism Tick paralysis Organophosphate poisoning |

| Muscle | Rhabdomyolysis |

| Emergent Diagnoses | |

| Cerebral cortex or subcortical | Tumor, abscess, demyelination |

| Brainstem | Demyelination |

| Spinal cord | Demyelination (transverse myelitis) Compression (disk, spondylosis) |

| Peripheral nerve | Compressive plexopathy (hematoma, aneurysm) Paraneoplastic vasculitis uremia |

| Muscle | Inflammatory myositis |

Diagnostic Algorithm

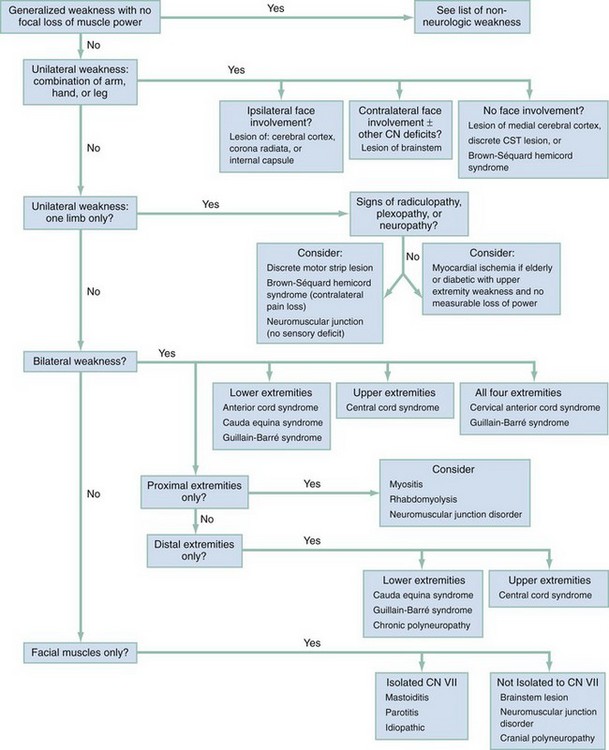

Deciphering loss of muscle power means following the pattern of a patient’s weakness from the myofiber back to a particular site within the central or peripheral nervous system (Fig. 13-1). Common clinical patterns of weakness can be classified and assessed as discussed in the following sections.

Unilateral Weakness with a Combination of Arm, Hand, or Leg with Ipsilateral Facial Involvement

This presentation is generally caused by a lesion in the contralateral cerebral cortex or the CSTs coursing down the corona radiata and forming the internal capsule. Mild forms can be limited to a loss of dexterity and coordination with hand movements. Moderate loss of power is termed paresis, and complete loss of motion is termed plegia. UMN signs are useful corroborative findings but may not always be present. Sensory disturbances commonly occur over the areas of weakness. Look for associated neglect, a visual field cut, or an expressive or receptive aphasia to localize the problem to the cortex.2 Patients with equal loss of strength to the face, hand, and leg are more likely to have a subcortical lesion disrupting all of these fibers as they funnel close together in the internal capsule. Concomitant headache is suggestive of a brain hemorrhage or mass lesion.3 Sudden onset of this weakness pattern implies hemorrhage or ischemia, whereas a gradual onset may be seen in demyelination or neoplasm.

Unilateral Weakness: A Combination of Arm, Hand, or Leg but with Contralateral Facial Involvement

This pattern indicates a brainstem lesion. A careful cranial nerve (CN) examination can provide more clues. If the patient has contralateral facial findings, there will likely be ptosis (CN III or sympathetic fibers) or a facial droop with forehead involvement (CN VII nucleus). Signs of CN V, VI, VIII, IX, or XII dysfunction will help to localize to a particular level within the brainstem.4 Cerebellar findings or nystagmus may also be present on examination. Sensory disturbances can parallel the weakness, and some patients will report double vision, trouble swallowing, slurred speech, vertigo, or nausea and vomiting. The CST courses ventrally through the brainstem, and extremity weakness with UMN signs in the involved limbs may accompany brainstem lesions. Depressed consciousness can also occur if the brainstem reticular activating system is involved. The two main underlying processes that cause unilateral extremity weakness with contralateral facial involvement are vertebrobasilar insufficiency and demyelinating diseases.

Unilateral Weakness: A Combination of Arm, Hand, or Leg without Facial Involvement

• A lesion in the medial, contralateral, cerebral homonculus (over the area where the lower extremity is represented)

• A discrete internal capsule or brainstem lesion involving only the corticospinal rather than the corticobulbar tracts

• Brown-Séquard hemicord syndrome if the patient also has contralateral hemibody pain and temperature sensory disturbances below the level of motor weakness

Unilateral Weakness: One Limb Only (Monomelic Weakness, Monoparesis, or Monoplegia)

Isolated weakness of one extremity is most commonly caused by a spinal cord or peripheral nerve lesion. Examination for UMN signs in the affected limb will help to uncover rare monomelic presentations of central nervous system lesions. If UMN signs such as hyper-reflexia or spasticity are present, a careful evaluation is performed for facial weakness or involvement of the contralateral or involvement of the contralateral or other ipsilateral limb as indicative of a central process. If weakness is in the entirety of one lower limb, one should ensure that the patient does not have a contralateral pinprick level indicative of Brown-Séquard hemicord syndrome. Monomelic weakness is often the result of a radiculopathy, plexopathy, peripheral neuropathy, or NMJ disorder. See Table 13-1 for emergent and critical peripheral nervous system diagnoses.

The examination for monomelic weakness presentations includes detailed strength testing and determination if weakness localizes to one ventral nerve root myotome or one particular peripheral nerve within the limb. Reflexes with a peripheral nerve disorder will be diminished, not hyperactive. Although radiculopathies can occasionally be purely motor, most peripheral lesions have some sensory component to their presentation; therefore a careful sensory examination in the distribution of dorsal nerve root dermatomes and peripheral nerves is essential. See Box 13-2 for a list of nonemergent causes of peripheral neuropathy.

If suspicion is low for a UMN source of isolated extremity weakness, reflexes are intact, and there are no sensory deficits to suggest a nerve or root problem, then NMJ disorders are considered. In such cases the weakness is often mild, fluctuating, and worse later in the day. It usually involves the proximal arm or leg muscles, wrist extensors, finger extensors, or ankle dorsiflexors. NMJ disorder–induced weakness with only monomelic symptoms will be an uncommon diagnosis in the ED (see Chapter 108). In elderly patients and others with significant cardiac risk factors, myocardial ischemia is considered if arm sensory symptoms or arm weakness that does not demonstrate measurable loss of motor power is reported.

Bilateral Weakness: Lower Extremities Only (Paraparesis or Paraplegia)

The first consideration with this presentation pattern is a spinal cord lesion. If this is the case, UMN signs may be absent in the acute period. Because the lateral spinothalamic tracts (LSTs) run in proximity to the CST, patients with bilateral lower extremity weakness frequently have alteration to their perception of pain or temperature. Examination may reveal a loss of pinprick sensation to a particular spinal level within the thoracic cord or terminal first lumbar segment. The lesion may be as high as T2 without producing upper extremity findings. The main causes of anterior cord syndrome are external compression, ischemia, or demyelination. In the absence of UMN signs or a clear thoracic pinprick level, evaluation of perianal sensation, rectal tone, and urinary retention can identify deficits that point to cauda equina syndrome—compression of peripheral nerve roots running below the termination of the spinal cord. If the physical examination does not support a cord syndrome or cauda equina compression, the patient may have a peripheral neuropathy affecting the longest nerve tracts first. The acute presentation that is most concerning is Guillain-Barré syndrome (GBS). Rapid demyelination of peripheral nerves can result in symmetrical weakness ascending from the feet. Sensory findings parallel the weakness, and reflexes should be decreased at some point in the patient’s clinical course.5

Bilateral Weakness: All Four Extremities without Facial Involvement (Quadriparesis or Quadriplegia)

Determination of sensory dermatomes by pinprick testing in the arms and hands along with strength testing of specific myotomes will allow localization of the level within the cervical spinal cord. One physical examination confounder with disorders that cause cord compression or ischemia is that upper extremity myotomes corresponding to the site of spine involvement will actually have LMN signs of flaccid weakness and decreased reflexes because anterior horn cells are involved at this particular level.6 However, UMN signs may be elicited below that level. A C5 lesion, for example, can cause diminished biceps reflexes but exaggerated triceps and patellar reflexes.

Bilateral Weakness: Proximal Portions of Extremities Only

Provided that there are no UMN signs and no sensory deficits, this pattern points to a myofiber disorder.7 Patients may report general fatigue or trouble raising the arms above the head, climbing stairs, or rising from a chair. The common acute and progressive causes of proximal muscular weakness are inflammatory diseases such as polymyositis or dermatomyositis, or necrosis as in rhabdomyolysis from HMG-CoA reductase inhibitors. Muscles are commonly but not always tender to palpation. Myositis patients can also have dysarthria and dysphagia from weakness of the pharyngeal muscles. Airway protective mechanisms may eventually be compromised.

Bilateral Weakness: Distal Portions of Extremities Only

This pattern is almost always caused by a peripheral neuropathy (see Box 13-2). Patients will have weakness and poor coordination with fine movements of their feet or hands. If this type of distal weakness is present in both lower extremities only, the patient will most likely have a chronic peripheral neuropathy or an acute demyelinating neuropathy (GBS). The patient will have some sensory disturbance over the feet as well. Examination for perianal sensory deficits or issues with fecal or urine continence will help to exclude the compressive polyradiculopathy of cauda equina syndrome as a cause of bilateral distal lower extremity weakness. If only the fingers and hands are involved, evaluation for central cord syndrome is performed. Bilateral lower cervical radiculopathies or symmetrical polyneuropathies are possible but much less likely.

Facial Weakness without Extremity Involvement

This will appear in one of two forms, as follows:

1. Unilateral facial droop. If the weakness is a result of a CN VII problem, unilateral weakness in the upper and lower half of the face should be present on examination. Causes for an isolated CN VII neuropathy are Bell’s palsy, mastoiditis, and parotitis. The examination must confirm that there is no extremity involvement and that other CNs, cerebellar testing results, and visual fields are normal. This will ensure that a brainstem lesion is not causing the weakness.

2. Facial weakness not limited to CN VII and the muscle of expression, but including some combination of ptosis, binocular diplopia, dysarthria, or dysphagia. This can be caused by a brainstem lesion, multiple cranial neuropathies, or an NMJ problem. If there are no cerebellar findings, visual field deficits, sensory disturbances, or extremity UMN signs, posterior cerebral circulation and brainstem disorders are less likely, and an NMJ disorder is more likely. Dysfunction of one or more ocular, facial, or pharyngeal muscles will be the most common presentation for NMJ pathology.8 The history may indicate that the facial weakness is acute and progressive (botulism) or chronic and fluctuating (myasthenia gravis). Signs of these diseases can be determined by examining extraocular motion, facial expression, and soft palate rise. Generalized fatigue is often reported, and neck, extremity, and respiratory muscle weakness caused by involvement of these neuromuscular units may be present on examination.9

Pivotal Findings

1. Patients with tachypnea or shallow respirations should be considered at higher risk for respiratory failure from diaphragmatic, intercostal, and accessory muscle fatigue. Consideration should be given to quantify respiratory effort with pulmonary function tests and/or intervene with positive pressure ventilation.

2. In any patient with sudden onset of focal weakness, a vascular cause (either occlusion or hemorrhage) is strongly considered until proven otherwise by an adequate imaging study.

3. The presence of a severe headache with unilateral weakness, or midline back pain with lower extremity weakness, alerts the emergency physician to a compressive space-occupying lesion.

4. Patients with UMN signs have weakness that localizes to the spinal cord CST or above and are considered to have an emergent problem. They may be at risk for progression to sympathetic autonomic failure or obtundation from enlarging space-occupying spinal or cerebral lesions, respectively.

5. The presence of anorectal or bladder insufficiency without another explanation suggests a UMN or cauda equina lesion.

6. Laboratory tests are most useful in excluding non-neuromuscular causes of weakness (electrocardiogram [ECG], hemoglobin, glucose, electrolytes, troponin, lactate, urinalysis). Two exceptions are creatinine kinase level in inflammatory myositis and potassium level in channelopathies.

Empirical Management

1. Neck and pharyngeal muscle weakness may herald a risk for aspiration or insufficiency of the diaphragm with paradoxical abdominal wall motion. Signs of inadequate hypopharyngeal muscle control or respiratory muscle fatigue should prompt protection of the airway and/or positive pressure ventilation.

2. During rapid sequence intubation (RSI), succinylcholine is avoided in suspected cases of progressive denervation of muscle. Nondepolarizing neuromuscular blocking agents such as rocuronium or vecuronium are used in this situation.

3. New quadriparesis or quadriplegia and hypotension without another cause is assumed to be caused by failure of autonomic sympathetic fibers in the cervical spinal cord. Consider a volume load and pressor support in addition to emergent imaging of this area.

4. Although new weakness localizing to the spinal cord or above calls for immediate imaging, weakness from the spinal roots down does not always necessitate imaging in the ED.

5. Patients with suspected GBS need pulmonary function testing in addition to admission to a critical care setting for further management.

6. An infectious or metabolic trigger is sought in patients with myasthenic crisis. If the patient is currently on acetylcholinesterase inhibitors, consideration should be given to a cholinergic crisis.

7. Be aware of medications that may worsen weakness in patients with NMJ disease (e.g., aminoglycosides, quinolones, beta-blockers).

8. Rhabdomyolysis is treated with aggressive fluid resuscitation and intervention directed at the primary cause, if known.

References

1. Pinto, A, Tuttolomondo, A, Di Raimondo, D, Fernandez, P, Licata, G. Cerebrovascular risk factors and clinical classification of strokes. Semin Vasc Med. 2004;4:287–303.

2. Yew, KS, Chang, E. Acute stroke diagnosis. Am Fam Physician. 2009;80:33–40.

3. Jamieson, DG. Diagnosis of ischemic stroke. Am J Med. 2009;122(4 Suppl 2):S14–S20.

4. Querol-Pascual, MR. Clinical approach to brainstem lesions. Semin Ultrasound CT MR. 2010;31:220–229.

5. McGillicuddy, DC, Walker, O, Shapiro, NI, Edlow, JA. Guillain-Barré syndrome in the emergency department. Ann Emerg Med. 2006;47:390–393.

6. Harrop, JS, Hanna, A, Silva, MT, Sharan, A. Neurological manifestations of cervical spondylosis. Neurosurgery. 2007;60:S14–S20.

7. Amato, AA, Barohn, RJ. Evaluation and treatment of inflammatory myopathies. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2009;80:1060–1068.

8. Newsom-Davis, J. The emerging diversity of neuromuscular junction disorders. Acta Myol. 2007;26:5–10.

9. Engstrom, JW. Myasthenia gravis: Diagnostic mimics. Semin Neurol. 2004;24:141–147.