Chapter 548 Vulvovaginal and Müllerian Anomalies

The sequence of events that occur in a developing embryo and early fetus to create a normal reproductive system includes cellular differentiation, duct elongation, fusion, resorption, canalization, and programmed cell death. Any of these processes can be interrupted during formation of the reproductive system, creating gonadal, müllerian, and/or vulvovaginal anomalies (see Table 548-1 on the Nelson Textbook of Pediatrics website at www.expertconsult.com). Genetic, epigenetic, enzymatic, and environmental factors all have some role in the process (see Table 548-2 on the Nelson Textbook of Pediatrics website at www.expertconsult.com)![]() . Most clinicians use the standard classification system adopted by the American Society for Reproductive Medicine (originally the American Fertility Society [AFS] classification). Others have proposed modified and more-detailed anatomic classification systems such as the modified AFS system or the VCUAM (vagina, cervix, uterus, and adnexa-associated malformation) system.

. Most clinicians use the standard classification system adopted by the American Society for Reproductive Medicine (originally the American Fertility Society [AFS] classification). Others have proposed modified and more-detailed anatomic classification systems such as the modified AFS system or the VCUAM (vagina, cervix, uterus, and adnexa-associated malformation) system.

Table 548-1 COMMON MÜLLERIAN ANOMALIES

| ANOMALY | DESCRIPTION |

|---|---|

| Hydrocolpos | Accumulation of mucus or nonsanguineous fluid in the vagina |

| Hemihematometra | Atretic segment of vagina with menstrual fluid accumulation |

| Hydrosalpinx | Accumulation of serous fluid in the fallopian tube, often an end result of pyosalpinx |

| Didelphic uterus | Two cervices, each associated with one uterine horn |

| Bicornuate uterus | One cervix associated with two uterine horns |

| Unicornuate uterus | Result of failure of one müllerian duct to descend |

Table 548-2 HERITABLE DISORDERS ASSOCIATED WITH MÜLLERIAN ANOMALIES

| MODE OF INHERITANCE | DISORDER | ASSOCIATED MÜLLERIAN DEFECT |

|---|---|---|

| Autosomal dominant | Camptobrachydactyly | Longitudinal vaginal septa |

| Hand-foot-genital | Incomplete müllerian fusion | |

| Autosomal recessive | Kaufan-McCusick | Transverse vaginal septa |

| Johanson-Blizzard | Longitudinal vaginal septa | |

| Renal-genital-middle ear anomalies | Vaginal atresia | |

| Fraser syndrome | Incomplete müllerian fusion | |

| Uterine hernia syndrome | Persistent müllerian duct derivatives | |

| Polygenic/multifactorial | Mayer-Rokitansky-Küster-Hauser syndrome | Müllerian aplasia |

| X linked | Uterine hernia syndrome | Persistent müllerian duct derivatives |

Embryology (Pathogenesis)

Phenotypic sexual differentiation, especially during formation of the vulvovaginal and müllerian systems, is determined from genetic (46,XX), gonadal, and hormonal influences (Chapter 576). The genetic sex of the embryo is determined at fertilization when the gamete pronuclei fuse. The primordial germ cells (oogonia or spermatogonia) migrate from the yolk sac to the gonadal ridges. The primitive gonads are indistinguishable until about the 7th wk of development. Gonadal development determines the progression or regression of the genital ducts and subsequent hormonal production and, thus, the external genitalia. Critical areas in the SRY region (sex-determining region on the Y chromosome) are believed to be the factors that drive the development of a testis from a primitive gonad as well as spermatogenesis. The testis begins to develop between 6 and 7 wk of gestation, first with Sertoli cells followed by Leydig cells, and testosterone production begins at about 8 wk of gestation. The genital tract begins to differentiate later than the gonads. The differentiation of the wolffian ducts begins with an increase in testosterone, and the local action of testosterone activates development of the epididymis, vas deferens, and seminal vesicle. Further male genital duct and external genital structures depend on the conversion of testosterone to dihydrotestosterone (DHT).

Clinical Manifestations

Vulvovaginal and müllerian anomalies can manifest at a variety of chronological time points during a female’s life: from infancy, through childhood and adolescence, and adulthood (see Table 548-1). The majority of external genitalia malformations manifest at birth, and often even subtle deviations from normal in either a male or female newborn warrant evaluation. Structural reproductive tract abnormalities can be seen at birth or can cluster at menarche or any time during a woman’s reproductive life. Some müllerian anomalies are asymptomatic, whereas others can cause gynecologic, obstetric, or infertility issues.

Laboratory Findings

Diagnosis of müllerian anomalies should include a physical exam, pelvic ultrasound, possibly MRI, and renal and skeletal inspections for associated anomalies. Renal anomalies are noted in 30-40% and skeletal anomalies are associated in 10-15% of patients with müllerian anomalies. Unilateral renal agenesis occurs in 15% of patients. The most common skeletal anomalies are vertebral. Patients usually have a normal female karyotype (46,XX), but several familial segregations and gene mutations and/or abnormal karyotypes have been reported (see Table 548-2). About 5-8% of patients with congenital müllerian anomalies have abnormal karyotypes. Most malformations are sporadic, with a polygenic mechanism and multifactorial etiology.

Uterine Anomalies

Uterine Didelphys

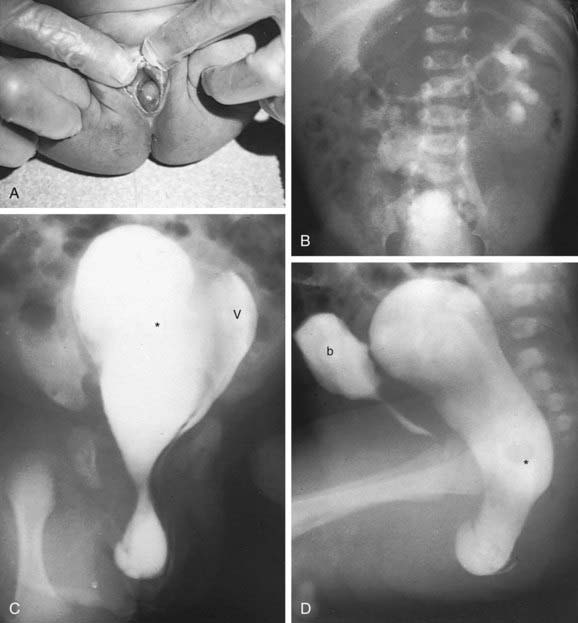

A uterine didelphys is the result a complete failure of fusion and represents 5% of müllerian anomalies. There are 2 fallopian tubes, 2 completely separate uterine cavities, 2 cervices, and often 2 vaginal canals or 2 partial canals because of an associated longitudinal vaginal septum (75% of the time). Evaluation for renal anomalies should be pursued because they are common as well. At times, the longitudinal septum attaches to 1 sidewall and obstructs 1 side of the vagina (or hemivagina). The combination of uterine didelphys, obstructed hemivagina, and ipsilateral renal agenesis is a variant of the broad spectrum of müllerian anomalies that is referred to as the Heryln-Werner-Wunderlich syndrome (HWWS) or obstructed hemivagina and ipsilateral renal anomaly (OHVIRA) syndrome in the literature (Fig. 548-1). Adolescents with this disorder usually present with abdominal pain shortly after menarche. Although there still may be a risk of adverse pregnancy outcomes with a uterine didelphys (preterm labor, malpresentation), overall pregnancy outcomes are generally good and are associated with less risk than in other uterine anomalies.

Vaginal Anomalies

Vulvar and Other Anomalies

American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Endometriosis in adolescents. ACOG committee opinion no. 310. Obstet Gynecol. 2005;105:921-927.

American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Vaginal “rejuvenation” and cosmetic vaginal procedures. ACOG committee opinion no. 378. Obstet Gynecol. 2007;110:737-738.

American Society for Reproductive Medicine. The American Fertility Society classification of adnexal adhesions, distal tubal occlusion, tubal occlusion secondary to tubal ligation, tubal pregnancies, müllerian anomalies and intrauterine adhesions. Fertil Steril. 1988;49:944-955.

Deutch TD, Abuhamad AZ. The role of 3-dimensional ultrasonography and magnetic resonance imaging in the diagnosis of müllerian duct anomalies. J Ultrasound Med. 2008;27:413-423.

Gell JS. Müllerian anomalies. Semin Reprod Med. 2003;21:375-388.

Laufer MR, Goldstein DP, Hendren WH. Structural abnormalities of the female reproductive tract. In: Emans SJ, Laufer MR, Goldstein DP, editors. Pediatric and adolescent gynecology. ed 5. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2005:334-416.

MacLaughlin DT, Donahoe PK. Sex determination and differentiation. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:367-378.

Miller RJ, Breech LL. Surgical correction of vaginal anomalies. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2008;51:223-236.

Olpin JD, Heilbrun M. Imaging of müllerian duct anomalies. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2009;52:40-56.

Oppelt P, Renner SP, Brucker S, et al. The VCUAM (vagina cervix uterus adnexa-associated malformation) classification; a new classification for genital malformations. Fertil Steril. 2005;84:1493-1497.

Rackow BW, Arici A. Reproductive performance of women with müllerian anomalies. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol. 2007;19:229-237.

Salim R, Woelfer B, Backos M, et al. Reproducibility of three-dimensional ultrasound diagnosis of congenital uterine anomalies. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2003;21:578-582.

Shulman LP. Müllerian anomalies. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2008;51:214-222.

Taylor E, Gomel V. The uterus and fertility. Fertil Steril. 2008;89:1-16.

of rudimentary horns are noncommunicating, some with a fibrous band connecting the 2 structures. Rudimentary horns can also communicate with the contralateral uterus. A fertilized ovum can implant and develop within a rudimentary horn. These pregnancies are incompatible with expectant gestation, and rupture of the horn could be life threatening. Rupture tends to occur at a later gestation than with an ectopic pregnancy, and hemorrhage is severe. Patients with rudimentary horns with functioning endometrium can also present with pain due to accumulating menses. Because the other horn has a normal outflow pathway, these patients present with pain, not primary amenorrhea. Pregnancies that arise in a unicornuate uterus are associated with increased preterm labor and delivery, malpresentation, and miscarriage.

of rudimentary horns are noncommunicating, some with a fibrous band connecting the 2 structures. Rudimentary horns can also communicate with the contralateral uterus. A fertilized ovum can implant and develop within a rudimentary horn. These pregnancies are incompatible with expectant gestation, and rupture of the horn could be life threatening. Rupture tends to occur at a later gestation than with an ectopic pregnancy, and hemorrhage is severe. Patients with rudimentary horns with functioning endometrium can also present with pain due to accumulating menses. Because the other horn has a normal outflow pathway, these patients present with pain, not primary amenorrhea. Pregnancies that arise in a unicornuate uterus are associated with increased preterm labor and delivery, malpresentation, and miscarriage.