Vulvar Squamous Lesions

Benign Squamous Neoplasms

Condyloma Acuminatum

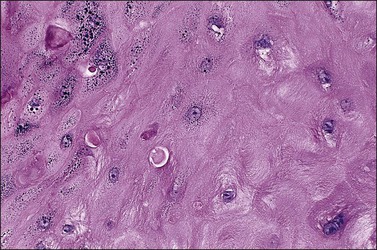

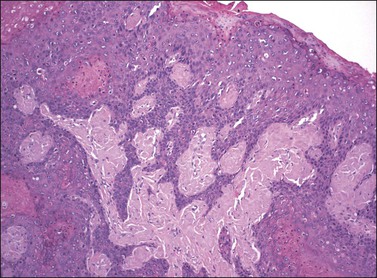

Microscopic Features

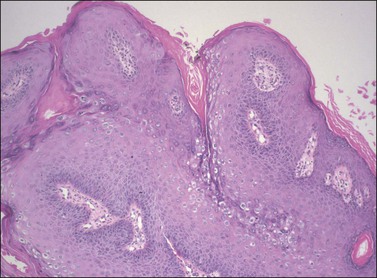

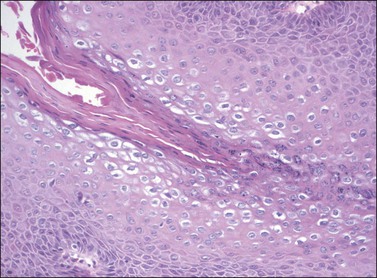

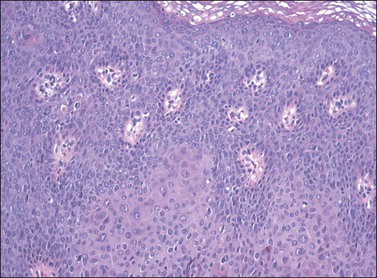

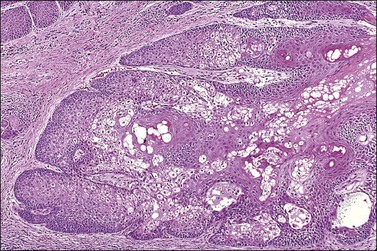

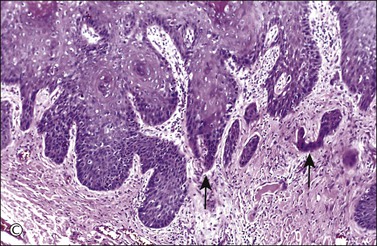

On histologic examination, the lesion consists of complex branching fibrovascular cores covered with acanthotic squamous epithelium, frequently with accompanying hyperkeratosis and parakeratosis. Pathognomonic findings include basal and parabasal hyperplasia, with koilocytic atypia, manifested by enlarged, hyperchromatic nuclei with irregular, wrinkled nuclear membranes accompanied by a region of perinuclear clearing or ‘halo,’ in the upper third of the epithelium (Figures 4.1 and 4.2).

Seborrheic Keratosis

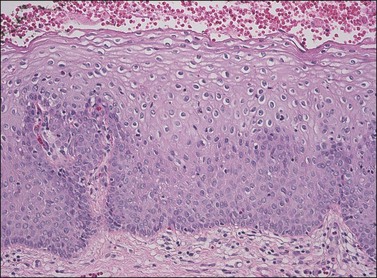

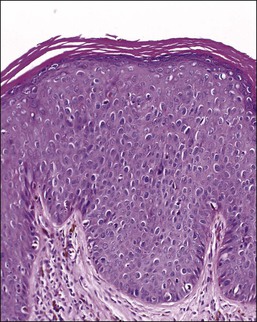

Microscopic Features

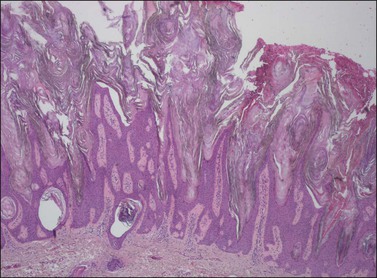

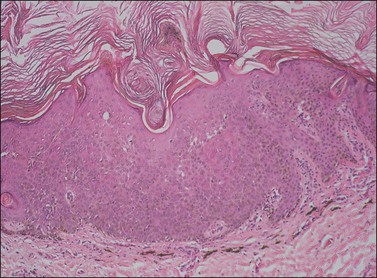

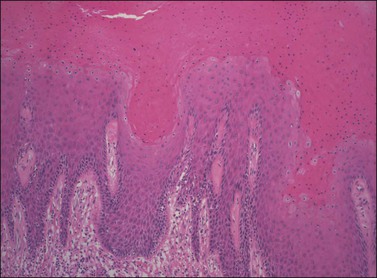

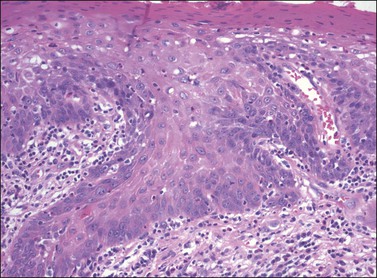

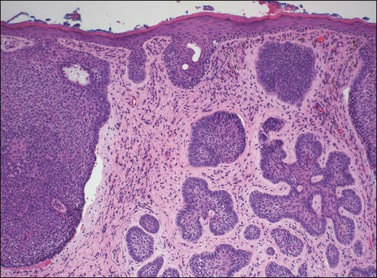

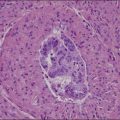

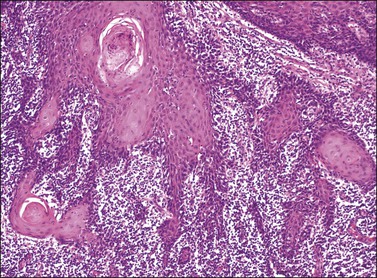

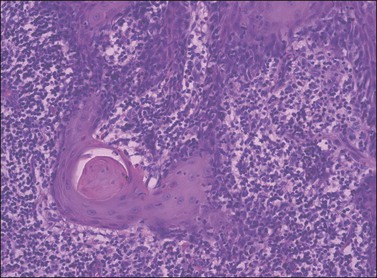

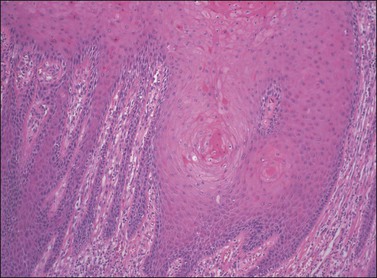

The epidermis is thickened by a population of cells with basaloid morphology, without significant nuclear atypia or mitotic activity, and with pronounced surface hyperkeratosis. Pigmentation of the basal and parabasal cells is usually evident. Invaginations of the surface epithelium result in the accumulation of hyperkeratotic material below the surface of the lesion, in what may appear to be cystic spaces, forming the structures known as ‘horn cysts’ (Figure 4.3). Follicular plugging with this hyperkeratosis is also typical. ‘Squamous eddies,’ rounded whorls of squamous cells named for their resemblance to swirling currents in a stream, may be found (Figure 4.4).

Differential Diagnosis

On occasion, reactive changes secondary to trauma or prominence of squamous eddies can be suggestive of squamous cell carcinoma. Key to establishing the correct diagnosis in such cases is the absence of an infiltrative growth pattern. Other entities in the differential diagnosis of seborrheic keratoses on the vulvar skin include condyloma acuminatum, VIN, and melanoma. The papillary architecture and hyperkeratosis of seborrheic keratosis can be suggestive of condyloma, particularly at low power. As seborrheic keratoses are frequently found to contain HPV DNA,1,2 some authors have maintained that these lesions are, in fact, variants of condyloma,3 although this remains controversial. The absence of koilocytic atypia in seborrheic keratosis and of keratin horn cysts in condylomata will usually resolve the diagnosis. The lack of significant nuclear atypia or mitotic activity is also of use to differentiate seborrheic keratosis from VIN and melanoma, with immunohistochemistry of further use in distinguishing the latter.

Keratoacanthoma

Definition

Keratoacanthoma is a distinctive keratinocytic neoplasm characterized by rapid growth and spontaneous regression. Although often considered a low-grade variant of squamous cell carcinoma, this view is not universally accepted,4–6 and as there have been no reported cases of malignant behavior in cases presenting on the vulva, we present it here as a benign neoplasm.

Clinical Features

Keratoacanthoma characteristically presents as a rapidly growing pink or flesh-colored, firm, well-demarcated dome-shaped lesion with central umbilication. Although common on the sun-exposed skin of the elderly, very few cases occurring on the vulva have been reported.7–10

Microscopic Features

The dome-shaped, umbilicated lesion observed on the skin corresponds to an endophytic proliferation of squamous cells forming a keratin-filled crater-like center rimmed by collarette, or ‘buttressing lips,’ of epidermis. The central squamous cells are well differentiated and tend to become larger toward the center of the proliferation, accumulating abundant glassy, eosinophilic cytoplasm (Figures 4.5 and 4.6). In the early stages of development, mitoses may be numerous and mild to moderate nuclear atypia may be present, but these features regress as the lesion matures, and when well developed only minimal atypia is present. The lesions typically have a rounded, pushing border with a dense inflammatory infiltrate at the base of the lesion.

Squamous Intraepithelial Lesions of the Vulva (VIN)

Definition

About 90% of squamous intraepithelial lesions of the vulva are HPV related, comprising a spectrum of alterations ranging from low-grade squamous intraepithelial lesions VIN (VIN 1), sometimes characterized as ‘flat condyloma,’ to the severe full-thickness dysplasia of high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion VIN (VIN 3). Recent proposals from both the International Society for the Study of Vulvovaginal Disease (ISVVD) and the College of Pathologists (CAP)/American Society for Colposcopy and Cervical Pathology (ASCCP) have advocated replacement of the older three-tiered system used to describe these lesions with a two-tiered system (Table 4.1).11–13

Table 4.1

Commonly Used Classification Schemes for Intraepithelial Disease of the Vulva

| 1986 VIN Terminology | 2009 ISSVD Terminology | 2012 CAP/ASCCP Terminology |

| VIN 1 | Condyloma HPV changes |

Low grade squamous intraepithelial lesion (VIN 1) |

| VIN 2 | VIN, usual type (uVIN) | High grade squamous intraepithelial lesion (VIN 2–3) |

| VIN 3 | VIN, usual type (uVIN) or VIN, differentiated type (dVIN) |

High grade squamous intraepithelial lesion (VIN 2–3) or VIN, differentiated type |

HPV-Related Low- and High-Grade Squamous Intraepithelial Lesions (VIN 1–3)

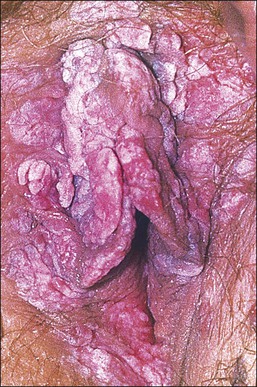

Clinical Features

Patients with HPV-related squamous intraepithelial lesions are usually in their thirties or forties, frequently smokers, and frequently have a history of, or concurrent, multifocal vulvar lesions and/or multicentric oncogenic HPV-related disease, or other sexually transmitted diseases.14–21 Pruritus is the most common symptom.20,21 Other symptoms may include pain, ulceration, or dysuria. Approximately 20% of patients are asymptomatic, but may have observed an abnormal area on self-examination.22,23

The gross appearance of the lesion is variable. Lesions are usually well demarcated and asymmetric, may appear red, white, pigmented, or mixed, and may be raised, papular, flat, or ulcerated (Figures 4.7 and 4.8).

Pathogenesis/Etiology

The majority of low-grade HPV-related vulvar squamous intraepithelial lesions (LSILs) contain low-risk HPV subtypes, while high-grade lesions (HSILs) typically contain high-risk subtypes, most commonly HPV 16. The estimated time of progression from incident infection to the development of clinical disease has been estimated at 18.5 months.23

Microscopic Features

LSIL of the Vulva (VIN 1).

Not all authors agree on the value or significance of the category of LSIL (VIN 1), although there is general agreement that it is a rare and poorly reproducible diagnosis.23–25 The controversy stems from disagreement as to the biologic behavior of these lesions.12,26–28 Because of its distinctive, albeit uncommon, morphology and its as yet unclear behavior, we prefer to maintain this diagnostic category for flat-macular lesions with epithelial changes resembling those of exophytic condylomata (Figure 4.9).

HSIL of the Vulva (VIN 2–3).

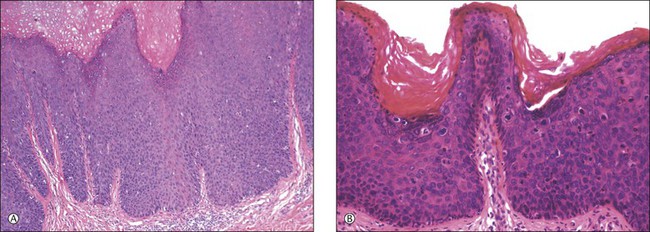

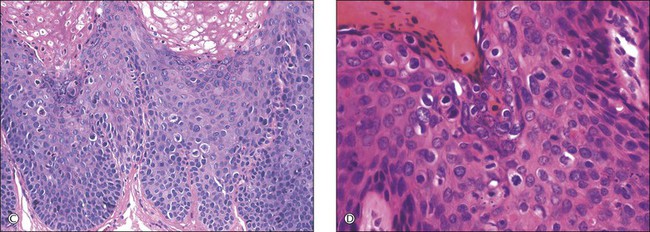

For descriptive purposes, high-grade HPV-related lesions of the vulva have been divided into warty and basaloid subtypes. Warty lesions (Figure 4.10A–D) are characterized by a spiky or undulating surface, giving them a condylomatous gross appearance. The markedly thickened epithelium forms wide, deep rete pegs separated by thin dermal papillae that often closely approach the surface. Disorganization and abundant mitotic figures, including abnormal ones, can be seen in all levels of the epithelium, with evidence of maturation and often koilocytic change in the upper layers. Hyperkeratosis is prominent, often with accompanying parakeratosis. Nuclei are enlarged and hyperchromatic, with irregular nuclear membrane contours and prominent pleomorphism. Multinucleated cells, as well as dyskeratotic cells, may be present. An appreciable amount of eosinophilic cytoplasm is present, and the cell borders are easily delineated. Lesions with this morphology were formerly subclassified as VIN 2 or VIN 3, by determination of the proportion of the epithelium populated by relatively immature cells, with those having immature cells involving no more than two-thirds of the epithelium classified as VIN 2 (Figure 4.11) and those having immature cells involving more than two-thirds of the epithelium as VIN 3.

Figure 4.10 (A) VIN 3, warty type, showing acanthosis, hyperkeratosis, and widened, deep rete ridges. (B) Extension of a long narrow dermal papilla close to the surface is seen in the center of this image. Numerous mitotic figures and dyskeratotic cells can be appreciated throughout all layers of the epithelium. (C) Marked nuclear pleomorphism in warty VIN 3, with surface hyperkeratosis and parakeratosis. (D) At high power, prominent nuclear atypia, numerous mitotic figures, apoptotic bodies, and dyskeratotic cells are easily identified.

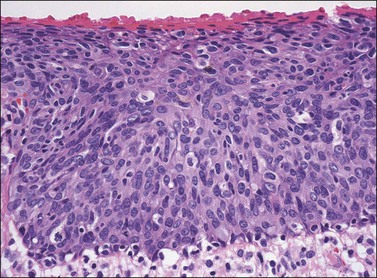

In contrast to warty lesions, the surface of basaloid lesions is relatively flat. Hyperkeratosis and koilocytosis may be present, but to a lesser degree than is seen in warty lesions. The epithelium is thickened by a relatively uniform population of immature cells with scant cytoplasm, poorly defined cell borders, and enlarged hyperchromatic nuclei (Figure 4.12). As in warty lesions, mitotic activity is readily identified and atypical mitotic figures may be present.

Figure 4.12 VIN 3, basaloid type. A disorganized proliferation of immature cells with nuclear atypia and polymorphism fills the entire thickness of the epithelium.

Distinction between warty and basaloid subtypes is not always easy. Mixed forms, containing morphologic features of both types, are not uncommon, and may be designated as such (Figure 4.13), although, as there is no clinical difference between lesions of either morphology, specification is not required for diagnosis.

Routine Biomarkers of Clinical Relevance

Immunohistochemistry for Ki-67 can be useful in identification of LSIL, where it can highlight an abnormal degree of proliferation in a cytologically equivocal lesion.28 Of greater utility in the diagnosis of HSIL is p16INK4a; as a reliable indicator of the presence of high-risk HPV in the vulva,19,29 it is strongly positive throughout most of the epithelium in HSIL (VIN 3).19,29,30

Differential Diagnosis

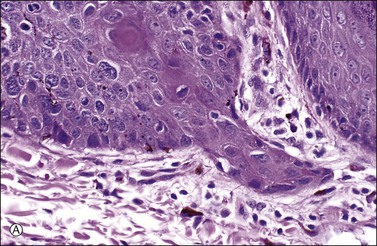

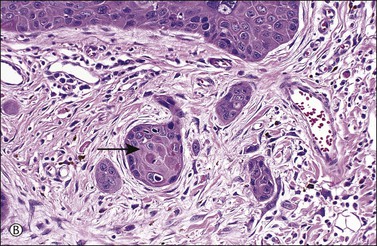

Although both condyloma acuminatum and warty HSIL (VIN 2–3) may have prominent koilocytic changes, the latter can be distinguished by the presence of atypical, pleomorphic cells in the deeper levels of the epithelium and by the presence of increased mitotic activity, including abnormal mitotic figures, in the upper layers. Seborrheic keratosis and lichen simplex chronicus may have acanthosis and hyperkeratosis, but typically lack the nuclear atypia of HSIL (VIN 2–3). Probably the most common diagnostic dilemma in assessment of HSIL (VIN 2–3) is distinction of truly intraepithelial disease from disease with associated early invasion. This can be complicated by involvement of skin appendages, which may extend quite deeply into the underlying dermis. The distinction rests on the preservation of a distinct epithelial–dermal junction, without an inflammatory response or stromal desmoplasia (Figure 4.14). The border along the basement membrane in intraepithelial lesions should be smooth, while in early invasion irregularly shaped tongues of cells protrude from the basal layer through the basement membrane (Figure 4.15). Often this is accompanied by ‘paradoxical maturation’ of the cells on the invasive front, with the cells enlarging and accumulating more abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm (Figure 4.16). Early invasive nests of squamous cell carcinoma are small, irregularly shaped, and usually accompanied by a desmoplastic response (Figure 4.17).

Figure 4.14 VIN 3 with skin appendage involvement. The cells of VIN 3 are palisaded along the periphery of the hair follicle. The involvement does not completely replace the normal epithelium in this case, and the terminal portion of the hair follicle and adjacent sebaceous gland are unaffected. Note how deep the hair follicle extends into the dermis compared with the adjacent epithelium.

Figure 4.15 Early invasion by squamous cell carcinoma, with irregular fingers and nests protruding into the dermis. Note the ‘paradoxical maturation’ of the cells toward the center of the larger cell groups.

Figure 4.16 ‘Paradoxical maturation’ with formation of a keratin pearl in an irregularly shaped protrusion of early invasion.

Figure 4.17 Microinvasive squamous cell cancer. (A) Early stromal invasion with a tiny tongue of tumor protruding from the basal most epithelium. (B) The small nests of tumor cells are distinctly separate from the overlying epidermis, sometimes have irregular shapes and lie in a desmoplastic stroma, and sometimes exhibit invasive cells with increased and more eosinophilic cytoplasm than neighboring basal cells. The microinvasive component is easy to recognize (arrow). (C) Some foci are easily recognized as microinvasive (arrows), whereas the bulbous tips of the overlying epidermis that are composed of small basal cells are considered as VIN 3.

Clinical Behavior and Treatment

The frequency of recurrence for HSIL (VIN 2–3) is estimated at over 50%,22 and is said to be more likely in patients who continue to smoke after initial diagnosis,18 in patients with multifocal disease,22 and in patients with involved margins on the initial resection, although the last association has not been a uniform finding.22 Several clinical risk factors for the progression of HSIL (VIN 2–3) to carcinoma have been identified, such as patient age, multicentricity, and multifocality of disease, and immunosuppression, but to date the data remain conflicting on all counts.14,16,17 Regardless of what the risk factors for progression may be, rates of progression are reported at 5.7–10%,14,21 and, untreated, HSIL (VIN 2–3) has been found to progress to carcinoma within 8 years.16 Treatment usually consists of wide local partial superficial vulvectomy or laser ablation.21,22 Topical treatments are available and currently under investigation, but to date none have been shown to be as effective as surgical treatment.21

High-Grade VIN, Differentiated or Simplex Type

Clinical Features

The ‘differentiated’ or ‘simplex’ type of VIN does not have an associated low-grade counterpart; all lesions with this morphology qualify as high grade. This type of VIN is not associated with HPV, and consequently the clinical presentation differs from that of HPV-related lesions in that patients are usually older (postmenopausal), are less often smokers, and rarely have multifocal or multicentric intraepithelial disease, but often have an associated benign vulvar condition, typically lichen sclerosus or lichen simplex chronicus.14,15,17,19–21 The symptoms and gross appearances of these lesions do not differ from those described for HPV-related lesions.

Pathogenesis/Etiology

Because of its frequent association with lichen sclerosus, long-standing lichen sclerosus has been implicated by some authors as a precursor lesion to differentiated VIN and associated carcinoma.15,17,19,21 Also implicated in the development of differentiated VIN is p53 mutation, and many studies have demonstrated the increased expression of p53 in the basal and suprabasal layers of the epithelium in these lesions.20,21,26,31–33

Microscopic Features

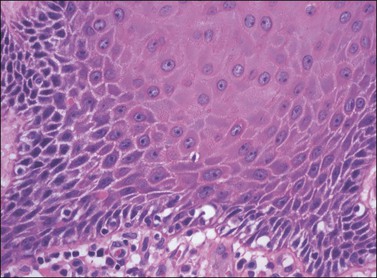

In differentiated VIN the most atypical cells are confined to the basal and parabasal layers of the epithelium, while the superficial layers of the epithelium often appear relatively normal, making it easy to overlook. The epithelium may be acanthotic (Figure 4.18), but can also be normal in thickness or even atrophic. An orderly pattern of keratinocyte maturation is present, in contradistinction to the disorder seen in warty and basaloid VIN. The rete pegs are typically elongated, narrow, and branched, and may show an anastomosing pattern (Figure 4.19). The basal cell layer is often expanded by the population of atypical basal and parabasal cells. These cells are characterized by hyperchromatic, irregular, and variably sized nuclei with coarse chromatin and prominent macronucleoli, and a moderate to abundant amount of hypereosinophilic cytoplasm indicative of premature keratinization (Figure 4.20). These cells may form whorled aggregates with or without keratin pearls in the basal portion of the epithelium (Figures 4.21 and 4.22).

Figure 4.19 Elongated rete ridges of VIN 3, differentiated type, with anastomosis of the rete on the left side of the image and whorls of differentiated squamous cells deep within the rete toward the right side.

Figure 4.20 Premature maturation of the cells toward the base in VIN 3, differentiated type. The cells contain abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm, clear cell borders with obvious intercellular bridges, and enlarged rounded nuclei with prominent nucleoli.

Routine Biomarkers of Clinical Relevance

Because differentiated VIN can be so difficult to recognize morphologically, there is great interest in identifying a ‘magic marker,’ which would distinguish it with greater ease. Hence, much has been made of the use of p53 immunostaining in these lesions, which is reported to show positive reactivity for p53 in the majority of the basal epithelial cells with superficial extension of this reactivity in 66–84% of cases.17,29,30,32,33 The immunoreactivity, however, is not always consistent throughout the lesion and a similar staining pattern can be seen in several other benign and malignant conditions.30,32,34 Moreover, p53 staining does not necessarily correlate with gene mutation, raising an additional concern as to the significance and utility of this finding.33,35 Thus, while p53 immunohistochemical study may be of value in confirming the diagnosis of differentiated VIN, it appears to be neither sensitive nor specific as a marker, and results must be interpreted with caution.

Intraoperative Consultation and Sampling/Tissue Issues

Specimens should be handled in the same fashion as HPV-related lesions.

Clinical Behavior and Treatment

There is strong evidence that differentiated VIN is more likely to progress than HPV-related VIN, with reported rates of progression of up to 33%,14,31 and it appears to do so at a more rapid rate as well.14,24,32 In one study comparing the association of the two types of VIN with preceding, concurrent, or subsequent invasive carcinoma, the rates were found to be 24.2% for high-grade HPV-related VIN and 83.3% for differentiated VIN.23 Given this very high association, a diagnosis of differentiated VIN often necessitates a more extensive excision than for HPV-related lesions.15,21

Squamous Cell Carcinoma

Clinical Features

Vulvar carcinoma is relatively uncommon, constituting approximately 4% of all malignancies of the female genital tract, and is most common in women of Caucasian descent.36 The vast majority of these tumors, estimated at 80–90%, are squamous cell carcinomas.37

While the frequency and incidence of HSIL (VIN 2–3) has been found to be increasing over the past 20 years,14,19,22,38 the incidence of squamous cell carcinoma has remained stable.21,38 At the same time, there has been a notable trend toward decreasing patient age at diagnosis for both HSIL (VIN 2–3)16,22 and squamous cell carcinoma.29 These epidemiologic changes have been attributed to numerous changing clinical factors, including increased prevalence of oncogenic HPV infection; increased awareness of the disease; an increased comfort in the discussion of, and willingness to seek care for, vulvar lesions on the part of younger patients; and an increased clinical knowledge of the disease and the use of biopsy to evaluate suspicious lesions and accomplish earlier diagnosis and treatment.14,21,22

Similar to their associated intraepithelial lesions, the clinical presentation of vulvar squamous cell carcinoma varies somewhat with the histologic subtype, as patients with HPV-related tumors tend not only to be younger, and more likely to have a history of other HPV-associated lesions,32 but also to present with advanced disease.37 The symptoms of vulvar cancer are similar to those of intraepithelial disease, and may include pruritus, vaginal discharge, dysuria, pain, bleeding, and ulceration. In some cases the patient may palpate or observe a mass. Early tumors may be asymptomatic, and occult carcinoma may be diagnosed on excised lesions clinically judged to be VIN in up to 20% of cases.12,39–42 Vulvar squamous cell carcinomas are most frequently located on the labia majora or minora and are typically solitary, with about 10% reported to be multifocal (Figures 4.23 and 4.24).43

Pathogenesis/Etiology

Increased understanding of the histopathogenesis of this disease has developed along with the changing epidemiology. Beginning in the early 1990s two distinct clinicopathologic groups of squamous cell carcinoma became distinguishable and it has become clear that two pathogenetic pathways exist for vulvar carcinoma, one HPV related and one not.44–47 Tumors associated with HPV appear to originate in HPV-positive high-grade VIN of warty and/or basaloid morphology and tend to have similar morphology, while tumors not associated with HPV appear to originate in differentiated VIN, or from some other process, and to have a keratinizing morphology.17,48,49 Those tumors with warty, basaloid, or mixed morphology, like the associated HSIL, typically occur in younger patients.20,23,27,50 While HPV-related HSIL is more commonly diagnosed than differentiated VIN, keratinizing carcinoma is the more common type of invasive tumor,21 indicating that HSIL either less likely to progress than is differentiated VIN or does so at a much slower rate, which explains why the increased diagnosis of intraepithelial disease has not led to a proportionate increase in squamous cell carcinoma.

The details of HPV-driven carcinogenesis have been well characterized in work on cervical cancer, and the mechanisms are presumed to be similar in the vulva and other sites where HPV-associated tumors present. The etiology and mechanisms behind the development of HPV-negative tumors remain somewhat obscure. A large proportion of them demonstrate immunohistochemical reactivity for p53,35,44 implicating p53 mutation in their pathogenesis. Additional studies have shown other genetic differences between HPV-positive and HPV-negative tumors.31 Ongoing investigation will undoubtedly provide more detailed understanding of this HPV-independent pathway.

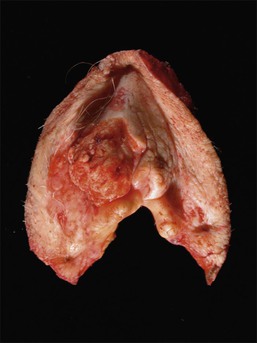

Gross Features

Gross features of vulvar carcinoma are highly variable. The tumor may be unrecognizable grossly, as in cases where occult tumor is found in resections for a diagnosis of VIN, or may be evident as an ulcer, a hyperkeratotic plaque, or an exophytic mass (Figures 4.25 and 4.26).

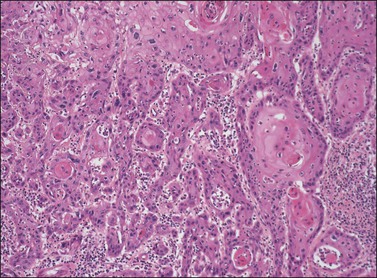

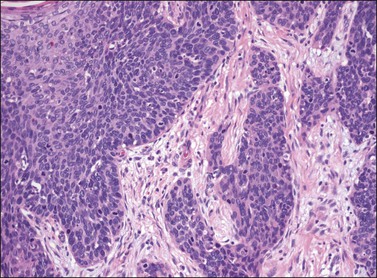

Microscopic Features

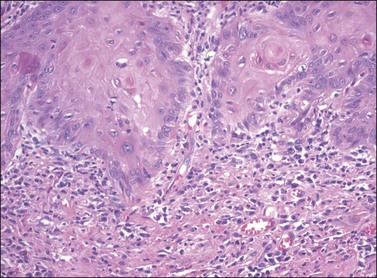

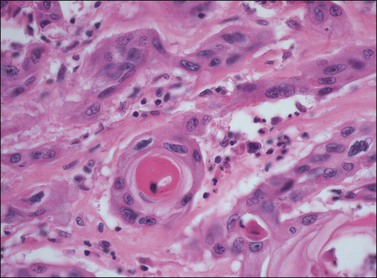

The three principal morphologic patterns seen in squamous cell carcinoma of the vulva are keratinizing, warty, and basaloid types. The majority of squamous cell carcinomas of the vulva are of the well-differentiated, keratinizing variety, and often arise on a background of lichen sclerosus with or without associated differentiated VIN. The morphology of these vulvar tumors is identical to those occurring elsewhere on the skin, and consists of irregularly shaped tongues and nests of squamous cells with abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm frequently showing whorling and forming keratin pearls (Figures 4.27 and 4.28). The cells may invade in broad fronds or in narrow finger-like projections with small clusters and single cells interspersed in irregular patterns. The nuclei show the same atypical features as those of differentiated VIN. Stroma surrounding the invasive tumor shows a desmoplastic response, and a chronic inflammatory response may be seen in the surrounding tissue.

Figure 4.28 Pronounced nuclear atypia and keratin pearl formation, characteristic of invasive squamous cell carcinoma.

Warty carcinoma is significantly less common, and is distinguished by its exophytic, papillary architecture and koilocytic change toward the epithelial surface. At the base of the lesion, irregularly shaped nests containing dyskeratotic cells and frequently keratin pearls are seen, similar to ordinary squamous cell carcinomas, but usually with a greater degree of nuclear pleomorphism and cytologic atypia (Figure 4.29). It is frequently associated with warty and/or basaloid VIN.

Figure 4.29 Squamous cell carcinoma, warty type. Irregular cords extend from a surface lesion with features typical of warty VIN.

Basaloid carcinoma is an uncommon tumor, consisting of variably sized nests of squamous cells showing little to no maturation. The cells are relatively uniform, with scant cytoplasm and oval nuclei containing evenly distributed, coarsely granular chromatin (Figure 4.30). It is also frequently associated with VIN, usually also of the basaloid type.

Figure 4.30 Basaloid carcinoma, comprising irregularly shaped nests of immature cells with scant cytoplasm invading the dermis and inducing a desmoplastic response. Associated VIN 3, basaloid type, is present on the left.

Rare cases of squamous cell carcinoma of the vulva, as elsewhere on the skin, have been described with sarcomatoid,51 plasmacytoid,52 and pseudoangiosarcomatous53 differentiation, as well as adenosquamous, giant cell, lymphoepithelioma-like, and papillary squamous cell carcinomas and some tumors that are not otherwise classifiable.46

Routine Biomarkers of Clinical Relevance

Similar to their VIN counterparts, warty and basaloid tumors are strongly associated with HPV, particularly type 16, and stain for p16INK4a.47–49 Keratinizing squamous cell carcinomas, like their precursor differentiated VIN, are usually HPV negative and negative for p16INK4a, but commonly reactive for p53.48,49

Differential Diagnosis

The distinction of early invasive carcinoma from VIN has been discussed previously. Other tumors in the differential diagnosis include malignant melanoma, keratoacanthoma, verrucous carcinoma, and basal cell carcinomas. Amelanotic melanomas, in particular, can be difficult to distinguish from squamous cell carcinoma, but can be distinguished by positive immunohistochemical stains for S-100, HMB-45, and Melan-A. Differentiation from keratoacanthoma, verrucous carcinoma, and basal cell carcinoma is discussed in the sections of this chapter on those respective lesions.

Intraoperative Consultation and Sampling/Tissue Issues

The majority of squamous cell carcinomas contain adjacent areas of high-grade VIN, with studies reporting the association in 45–100%.42–44,48 Because concurrent VIN is so often present in these cases, it is important to sample any unusual looking area of the epithelium, even if it is at some distance from the obvious tumor. Likewise, all margins must be sampled even in the absence of gross disease to ensure they are free of intraepithelial disease as well as invasive tumor.

Clinical Behavior and Treatment

The most recent (2009) International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics (FIGO) staging system, correlated with the current American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) TNM staging, is shown in Table 4.2, and survival rates by stage are shown in Table 4.3. These data demonstrate the prognostic significance of tumor size, depth of invasion, and extent of local spread, and it is important to include such information in the pathologic report of vulvectomy specimens. A thorough and updated protocol (checklist) for the evaluation of vulvar carcinoma specimens has recently been published by CAP and can be used for further guidance on reporting these cases.

Table 4.2

Vulvar Tumor Pathologic Staging

| Primary Tumor (pT) | FIGO Stage |

| pTX: | — |

| Primary tumor cannot be assessed | |

| pT0: | — |

| No evidence of primary tumor | |

| pTis: | — |

| Carcinoma in situ | |

| pT1a: | IA |

| Lesions 2 cm or less in size, confined to vulva or perineum, and with depth of stromal invasion 1.0 mm or less | |

| pT1b: | IB |

| Lesions more than 2 cm in size or any size with depth of stromal invasion more than 1.0 mm, confined to the vulva or perineum | |

| pT2: | II |

| Tumor of any size with extension to any adjacent perineal structures including lower/distal one-third urethra, lower/distal one-third vagina, or anal involvement | |

| pT3: | IVA |

| Tumor of any size with extension to any of the following structures: upper/proximal two-thirds urethra, upper/proximal two-thirds vagina, bladder mucosa, rectal mucosa, or fixed to pelvic bone | |

| Regional Lymph Nodes (pN) | |

| pNx: Regional lymph nodes cannot be assessed |

|

| pN0: No regional lymph node metastasis |

|

| pN1: | |

| N1a: One or two lymph node metastases, each less than 5 mm |

IIIA |

| N1b: One lymph node metastasis 5 mm or greater |

IIIA |

| pN2: | |

| pN2a: Three or more lymph node metastases each less than 5 mm |

IIIB |

| pN2b: Two or more lymph node metastases each 5 mm or greater |

IIIB |

| pN2c: Lymph node metastasis with extracapsular spread |

IIIC |

| pN3: | IVA |

| Fixed or ulcerated regional lymph node metastasis | |

| Distant Metastasis (pM) | |

| pM0: No distant metastasis |

|

| pM1: | IVB |

| Distant metastasis (including pelvic lymph node metastasis) |

Based on AJCC/UICC TNM, 7th edition (2010) and FIGO 2009 Annual Report and College of American Pathologists, 2010.

Table 4.3

Survival Rates for Squamous Cell Carcinoma by Stage

| FIGO Stage | Relative 5 Year Survival Rate | Relative 10 Year Survival Rate |

| I | 93% | 87% |

| II | 79% | 69% |

| III | 53% | 46% |

| IV | 29% | 16% |

Adapted from www.cancer.org

The measurement of the depth of invasion warrants further discussion, as there is often some confusion as to the difference between tumor thickness and tumor depth. In the vulva, measurement of depth of invasion has been standardized as the measurement from the epithelial/dermal junction of the adjacent most superficial dermal papilla to the point of deepest invasion. Proper measurement of this depth is of critical importance, as a depth of 1 mm or less in a solitary tumor measuring no more than 2 cm in greatest dimension defines a specific subset of tumors with distinct clinicopathologic features. These tumors, designated as AJCC stage T1a (FIGO IA) or, more recently, by the CAP/ASCCP as ‘superficially invasive squamous cell carcinomas (SISCCA),’16 have a negligible risk of nodal dissemination, and an excellent prognosis.54,55 There are few data on tumors with a depth of invasion of 1.1–2 mm, but it appears that once the depth of invasion exceeds 2 mm there is clearly a risk of nodal metastases, with recurrences associated with decreased survival. The risks increase with progressive depth of invasion.56,57 Accordingly, treatment for SISCCA may be limited to partial deep vulvectomy without lymphadenectomy, while tumors with invasion greater than 1 mm require excision of the ipsilateral inguinal nodes as well.58,59 Bilateral groin dissections are advised if the lesion is in the midline or ipsilateral nodes are positive.59 There has been a shift in recent years toward increasingly conservative surgery, and total deep vulvectomy with bilateral groin dissection in one large, continuous block, once routine for vulvar carcinomas, is now rarely performed.58 On the rare occasion when the disease is extremely extensive or advanced at the time of diagnosis, chemotherapy and radiation, rather than surgery, may be the initial treatment of choice, but such nonsurgical treatments have been found to have little value in preventing recurrent disease.59 Vulvar carcinoma spreads locally into adjacent structures, commonly extending into the vagina and distal urethra, and in advanced cases into the base of the bladder, pelvic bones, rectum, and perirectal tissues. Lymphovascular spread may occur, most commonly involving first the inguinofemoral lymph nodes and then spreading to the deeper pelvic nodes. From there spread may extend to the para-aortic nodes and from there drain into the thoracic duct, from which metastasis to other distant sites may occur by hematogenous dissemination.

Adequate surgical resection is said to achieve local control of disease in 80–90% of cases, even when inguinal lymph nodes are positive.59 Local recurrence on the vulva is three times more common than recurrence in the groin, pelvis, or distant sites, and carries a better prognosis.59 Factors associated with an increased risk of local recurrence are margins positive for tumor or VIN, margins less than 8 mm from invasive tumor, the presence of lymphovascular space invasion, greater depth of invasion, and large tumor size.58,59 The next most frequent site of recurrence is the groin, and when this occurs the prognosis is guarded, with the majority of patients succumbing to disease within 2 years.57,59 Overall, recurrences most frequently occur in the first 2 years following surgery.57 Patients with positive inguinal lymph nodes are more likely to have recurrence of tumor, and the risk is increased if the nodal involvement is bilateral.57,59 Recurrences in the pelvis or distant sites are uncommon, but nearly always fatal.59 It should be recognized that a fair number of recurrences occur 5 years or later from the initial surgery,57 and long-term follow-up is imperative.

Uncommon Subtypes of Squamous Cell Carcinoma

Verrucous Carcinoma

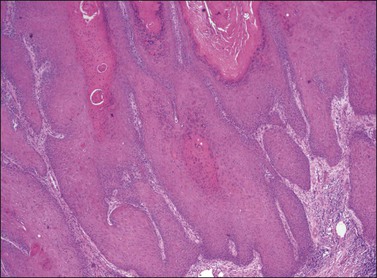

Microscopic Features

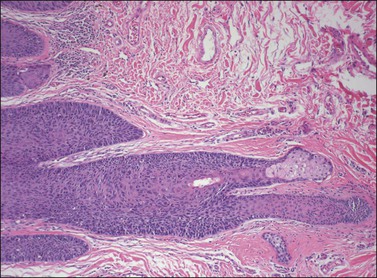

Verrucous carcinoma is characterized by an acanthotic epithelial proliferation of well-differentiated squamous cells with abundant cytoplasm and minimal nuclear atypia or pleomorphism. Abundant hyperkeratosis and parakeratosis is typically present on the surface. The tumor expands and elongates the rete ridges, producing large bulbous nests along the base that advance into the underlying dermis in a pushing, rather than an infiltrative, pattern, which is a distinguishing characteristic of this tumor (Figures 4.31–4.33). A chronic inflammatory infiltrate is commonly found along this advancing border.

Differential Diagnosis

The warty architecture of verrucous carcinoma can suggest a diagnosis of condyloma or warty VIN. The lack of fibrovascular cores within the papillary epithelial formations of verrucous carcinoma as well as the absence of nuclear atypia or koilocytic change will aid in this distinction. It is also important to distinguish verrucous carcinoma from exophytic squamous cell carcinomas of either the warty or keratinizing type, in which cases the characteristic bulbous downgrowths of the rete pegs in verrucous carcinoma, forming a pushing rather than an infiltrative margin, should distinguish it.

Clinical Behavior and Treatment

Although the tumor may be locally aggressive and has a tendency to recur,60 it very rarely metastasizes, and, in fact, the finding of lymph node metastasis strongly mitigates against the diagnosis and should prompt a thorough re-evaluation of the lesion for areas of typical squamous cell carcinoma. Treatment consists of wide local excision without lymph node dissection.

Basal Cell Carcinoma

Basal cell carcinoma is a very common cutaneous tumor, but rare on the vulvar skin, constituting only 1–3% of all vulvar cancers.61–63 They occur primarily in elderly white women, and the symptoms are similar to those of typical squamous cell carcinoma. The lesions are always solitary and present as firm, well-circumscribed, hypopigmented nodules or plaques, which may ulcerate as the disease progresses. The etiology of this tumor on the sun-exposed skin, where it is a common occurrence, is believed to be exposure to ultraviolet radiation, but the etiology of lesions of the vulva remains obscure. There is no association of basal cell carcinoma with HPV infection.

Microscopic Features

The histologic appearance of basal cell carcinoma of the vulva is no different from that of such tumors elsewhere on the skin. Numerous architectural patterns may occur, alone or in combination, but the features described here are common to most of them. The tumors are composed of small, uniform cells with hyperchromatic, elongated nuclei and scant cytoplasm, and may show abundant mitotic figures and apoptotic bodies. Most tumors maintain a connection with the basal surface of the overlying epithelium, and grow downward in lobules or nests that characteristically show peripheral palisading of the nuclei with haphazard distribution of the cells toward their centers. The tumor nests are embedded in a loose fibrous stroma that may show myxoid change, and frequently a cleft-like retraction space is seen between the tumor cells and this stroma (Figure 4.34).

Clinical Behavior and Treatment

As in basal cell carcinoma elsewhere on the skin, basal cell carcinoma of the vulva may be locally invasive and may recur locally, but metastasis is very rare.61–63 Wide local excision is the treatment of choice, and the prognosis is excellent with the exception of those very rare cases that do metastasize, in which case the disease is rapidly fatal.61–63

Sebaceous Carcinoma

Sebaceous carcinoma is a rare, aggressive neoplasm originating from the sebaceous glands of the skin. It is most commonly seen on the eyelid, but rare cases involving the vulva have been reported, a few of which have been associated with VIN.64–66 It is composed of malignant cells in lobules, tongues, or small clusters in a fibrovascular stroma. The large cells, with large nuclei containing prominent nucleoli and abundant cytoplasm, have a squamoid appearance, particularly at low power. At higher magnification, sebaceous differentiation is manifested by the presence of intracellular lipid producing foaminess or fine vacuolization of the cytoplasm, which may produce scalloping of the edges of the nuclei (Figure 4.35). These sebaceous features are often most prominent toward the center of the cell nests. The tumor may be very deeply invasive, and may metastasize to lymph nodes or distant sites, which must be taken into account when planning for its excision.

References

1. Gushi, A, Kanekura, T, Kanzaki, T, Eizuru, Y. Detection and sequences of human papillomavirus DNA in nongenital seborrheic keratosis of immunocompetent individuals. J Dermatol Sci. 2003; 31(2):143–149.

2. Bai, H, Cviko, A, Granter, S, et al. Immunophenotype and viral (human papillomavirus) correlates of vulvar seborrheic keratosis. Hum Pathol. 2003; 34(6):59–64.

3. Li, J, Ackerman, AB. eborrheic keratosis’ that contain human papillomavirus are condyloma acuminate. Am J Dermatopathol. 1994; 16(4):398–405.

4. Karaa, A, Khachemoune, A. Keratoacanthoma: a tumor in search of a classification. Int J Dermatol. 2007; 46(7):671–678.

5. Schwartz, R. Keratoacanthoma: a clinico-pathologic enigma. Dermatol Surg. 2004; 30(2 Pt 2):326–333.

6. Weedon, D, Malo, J, Brooks, D, Williamson, R. Keratoacanthoma: is it really a variant of squamous carcinoma? ANZ J Surg. 2010; 80(3):129–130.

7. Chen, W, Koenig, C. Vulvar keratoacanthoma: a report of two cases. Int J Gynecol Pathol. 2004; 23(3):284–286.

8. Gilbey, S, Moore, D, Look, K, Sutton, G. Vulvar keratoacanthoma. Obstet Gynecol. 1997; 89(5 Pt 2):848–850.

9. Ozcan, F, Bilgic, R, Cesur, S. Vulvar keratoacanthoma. APMIS. 2006; 114(7–8):562–565.

10. Nascimento, M, Cominos, D, Davies, N, Obermair, A. Vulval keratoacanthoma. Gynecol Oncol. 2005; 97(2):674–676.

11. Wilkinson, EJ, Kneale, B, Lynch, PJ. Report of the ISVVD Terminology Committee. J Reprod Med. 1986; 31:973–974.

12. Heller, DS. Report of a new ISSVD classification of VIN. J Low Genit Tract Dis. 2007; 11(1):46–47.

13. Darragh, T, Colgan, T, Cox, JT, et al. The Lower Anogenital Squamous Terminology Standardization Project for HPV-Associated Lesions: background and consensus recommendations from the College of American Pathologists and the American Society for Colposcopy and Cervical Pathology. J Low Genit Tract Dis. 2012; 16(3):205–242.

14. Van de Nieuwenhof, H, Massurger, L, van der Avoort, I, et al. Vulvar squamous cell carcinoma development after diagnosis of VIN increases with age. Eur J Cancer. 2009; 45(5):851–856.

15. Terlou, A, Blok, L, Helmerhorst, T, Beurden, M. Premalignant epithelial disorders of the vulva: squamous vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia, vulvar paget’s disease and melanoma in situ. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2010; 89(6):741–748.

16. Jones, R, Rowan, D, Stewart, A. Vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia: aspects of the natural history and outcome of 405 women. Obstet Gynecol. 2005; 106(6):1319–1326.

17. Hart, W. Vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia: historical aspects and current status. Int J Gynecol Pathol. 2001; 20(1):16–30.

18. Khan, AM, Freeman-Wang, T, Pisal, N, Singer, A. Smokers and multicentric vulval intraepithelial neoplasia. J Obstet Gynaecol. 2009; 29(2):123–125.

19. McCluggage, WG. Recent developments in vulvovaginal pathology. Histopathology. 2009; 54(2):156–173.

20. de Bie, RP, van de Nieuwenhoof, HP, Bekkers, RLM, et al. Patients with usual vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia-related vulvar cancer have an increased risk of cervical abnormalities. Br J Cancer. 2009; 101(1):27–31.

21. Van de Nieuwenhof, HP, van der Avoort, IAM, de Hullu, JA. Review of squamous premalignant vulvar lesions. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2008; 68(2):131–156.

22. McNally, OM, Mulvany, NJ, Pagano, R, et al. VIN 3: a clinicopathologic review. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2002; 12(5):490–495.

23. Skapa, P, Zamecnik, J, Hamsikova, E, et al. Human papillomavirus (HPV) profiles of vulvar lesions: possible implications for the classification of vulvar squamous cell carcinoma precursors and for the efficacy of prophylactic HPV vaccination. Am J Surg Pathol. 2007; 31(12):1834–1843.

24. Preti, M, Mezzetti, M, Robertson, C, Sideri, M. Inter-observer variation in histopathological diagnosis and grading of vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia: results of an European collaborative study. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 2000; 107(5):594–599.

25. Garland, S, Insinga, R, Sings, H, et al. Human papilloma virus infections and vulvar disease. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2009; 18(6):1777–1784.

26. Srodon, M, Stoler, M, Baber, G, Kurman, R. The distribution of low and high risk HPV types in vulvar and vaginal intraepithelial neoplasia. Am J Surg Pathol. 2006; 30(12):1513–1518.

27. Van der Avoort, IAM, Shirango, H, Hoevanaars, BM, et al. Vulvar squamous cell carcinoma as a multifactorial disease following two separate and independent pathways. Int J Gynecol Pathol. 2005; 25(1):22–29.

28. Logani, S, Lu, D, Quint, W, et al. Low-grade vulvar and vaginal intraepithelial neoplasia: correlation of histologic features with human papillomavirus DNA detection and MIB-1 immunostaining. Mod Pathol. 2003; 16(8):735–741.

29. Hoevenaars, BM, van der Avoort, I, de Wilde, P, et al. A panel of p16INK4a, MIB-1 and p53 proteins can distinguish between the 2 pathways leading to vulvar squamous cell carcinoma. Int J Cancer. 2008; 123(12):2767–2773.

30. Santos, M, Montagut, C, Mellado, B, et al. Immunohistochemical staining for p16 and p53 in premalignant and malignant epithelial lesions of the vulva. Int J Gynecol Pathol. 2004; 23(3):206–214.

31. Yang, B, Hart, W. Vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia of the simplex (differentiated) type: a clinicopathologic study including analysis of HPV and p53 expression. Am J Surg Pathol. 2000; 24(2):429–441.

32. Mulvany, N, Allen, D. Differentiated intraepithelial neoplasia of the vulva. Int J Gynecol Pathol. 2007; 27(1):125–135.

33. Pinto, A, Miron, A, Yassin, Y, et al. Differentiated vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia contains Tp53 mutations and is genetically linked to vulvar squamous cell carcinoma. Mod Pathol. 2010; 23(3):404–412.

34. Medeiros, F, Nascimento, A, Crum, C. Early vulvar squamous neoplasia: advances in classification, diagnosis, and differential diagnosis. Adv Anat Pathol. 2005; 12(1):20–26.

35. Rolfe, KJ, MacLean, AB, Crow, JC, et al. TP53 mutations in vulval lichen sclerosus adjacent to squamous cell carcinoma of the vulva. Br J Cancer. 2003; 89(12):2249–2253.

36. Saraiya, M, Watson, M, Wu, X, et al. Incidence of in situ and invasive vulvar cancer in the US, 1998–2003. Cancer. 2008; 113(110 Suppl):2865–2872.

37. Tyring, S. Vulvar squamous cell carcinoma: guidelines for early diagnosis and treatment. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2003; 189(3 Suppl):S17–S23.

38. Lanneau, G, Argenta, P, Lanneau, M, et al. Vulvar cancer in young women: demographic features and outcome evaluation. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2009; 200(6):645.e1–645.e5.

39. Husseinzadeh, N, Recinto, C. Frequency of invasive cancer in surgically excised vulvar lesions with intraepithelial neoplasia (VIN 3). Gynecol Oncol. 1999; 73(1):119–120.

40. Chafe, W, Richards, A, Morgan, L, Wilkinson, E. Unrecognized invasive carcinoma in vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia (VIN). Gynecol Oncol. 1988; 31(1):154–162.

41. Van Seters, M, van Beurden, M, deCraen, A. Is the assumed natural history of vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia III based on enough evidence? A systematic review of 3322 published patients. Gynecol Oncol. 2005; 97(2):645–651.

42. Poltrerauer, S, Dressler, A, Grimm, C, et al. Accuracy of preoperative vulva biopsy and the outcome of surgery in vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia 2 and 3. Int J Gynecol Pathol. 2009; 28(6):559–562.

43. Kurman, RJ, Ronnett, BM, Sherman, ME, Wilkinson, EJ. Tumors of the cervix, vagina and vulva, 4th series ed. Washington, DC: American Registry of Pathology; 2010.

44. Gargano, JW, Wilkinson, EJ, Unger, ER, et al. Prevalence of human papillomavirus types in invasive vulvar cancers and vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia 3 in the United States before vaccine introduction. J Low Genit Tract Dis. 2012; 16(4):471–479.

45. Chiesa-Vottero, A, Dvoretsky, P, Hart, WR. Histopathologic study of thin vulvar squamous cell carcinomas and associated cutaneous lesions: a correlative study of 48 tumors in 44 patients with analysis of adjacent vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia types and lichen sclerosus. Am J Surg Pathol. 2006; 30(3):310–318.

46. Santos, M, Landolfi, S, Olivella, A, et al. p16 overexpression identifies HPV-positive vulvar squamous cell carcinomas. Am J Surg Pathol. 2006; 30(11):1347–1356.

47. De Vuyst, H, Clifford, G, Nascimento, M, et al. Prevalence and type distribution of human papillomavirus in carcinoma and intraepithelial neoplasia of the vulva, vagina and anus: a meta-analysis. Int J Cancer. 2009; 124(7):1626–1636.

48. Quddus, M, Xu, C, Steinhoff, MM, et al. Simplex (differentiated) type VIN: absence of p16INK4 supports its weak association with HPV and its probable precursor role in non-HPV related vulvar squamous cancers. Histopathology. 2005; 46(6):709–722.

49. Eva, L, Ganesan, R, Chan, K, et al. Differentiated-type vulval intraepithelial neoplasia has a high-risk association with vulval squamous cell carcinoma. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2009; 19(4):741–744.

50. Messing, M, Gallup, D. Carcinoma of the vulva in young women. Obstet Gynecol. 1995; 86(1):51–54.

51. Choi, D, Lee, J, Lee, S, et al. Squamous cell carcinoma with sarcomatoid features of the vulva: a case report and review of literature. Gynecol Oncol. 2006; 103(1):363–367.

52. Tran, T, Carlson, J. Plasmacytoid squamous cell carcinoma of the vulva. Int J Gynecol Pathol. 2008; 27(4):601–605.

53. Horn, L-C, Liebert, U, Edelmann, J, et al. Adenoid squamous carcinoma (pseudoangiosarcomatous carcinoma) of the vulva: a rare but highly aggressive variant of squamous cell carcinoma-a report of a case and review of the literature. Int J Gynecol Pathol. 2008; 27(2):288–291.

54. Yoder, B, Rufforny, I, Massoll, N, Wilkinson, E. Stage 1A vulvar squamous carcinoma: an analysis of tumor invasive characteristics and risk. Am J Surg Pathol. 2008; 32(5):765–772.

55. Herod, JJ, Shafi, MI, Rollason, TP, et al. Vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia with superficially invasive carcinoma of the vulva. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1996; 103(5):453–456.

56. Binder, SW, Huang, I, Fu, YS, et al. Risk factors for the development of lymph node metastasis in vulvar squamous cell carcinoma. Gynecol Oncol. 1990; 37(1):9–16.

57. Bosquet, J, Magrina, J, Gaffey, T, et al. Long-term survival and disease recurrence in patients with primary squamous cell carcinoma of the vulva. Gynecol Oncol. 2005; 97(3):828–833.

58. Preti, M, Rouzier, R, Mariani, L, Wilkinson, E. Superficially invasive carcinoma of the vulva: diagnosis and treatment. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2005; 48(4):862–868.

59. Stehman, F, Look, K. Carcinoma of the vulva. Obstet Gynecol. 2006; 107(3):719–733.

60. Gualco, M, Bonin, S, Foglia, G, et al. Morphologic and biologic studies on ten cases of verrucous carcinoma of the vulva supporting the theory of a discrete pathologic entity. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2003; 13(3):317–324.

61. Piuria, B, Rabinovich, A, Dgani, R. Basal cell carcinoma of the vulva. J Surg Oncol. 1999; 70(3):172–176.

62. Mulayim, N, Silver, D, Ocal, I, Bablola, E. Vulvar basal cell carcinoma: two unusual presentations and review of the literature. Gynecol Oncol. 2001; 85(3):532–537.

63. de Giorgi, V, Salvini, C, Massi, D, et al. Vulvar basal cell carcinoma: retrospective study and review of literature. Gynecol Oncol. 2005; 97(1):192–194.

64. Esconilla, P, Grilli, R, Canamero, M, et al. Sebaceous carcinoma of the vulva. Am J Dermatol. 1999; 21(15):468–472.

65. Carlson, J, McGlennen, R, Gomez, R, et al. Sebaceous carcinoma of the vulva: a case report and review of the literature. Gynecol Oncol. 1996; 60(30):489–491.

66. Khan, Z, Misra, G, Fiander, A, Dallimore, N. Sebaceous carcinoma of the vulva. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 2003; 110(2):227–228.