Vulvar Mesenchymal Neoplasms and Tumor-Like Conditions

Tumor-Like Conditions

Fibroepithelial–StromAl Polyp (Pseudosarcoma Botryoides)

Clinical Features

Fibroepithelial–stromal polyps, which are hormonally sensitive, most commonly occur in the vulvovaginal region of reproductive age women, often during pregnancy. They may, however, also occur in postmenopausal women on hormonal replacement therapy. Often, the polyps are incidental findings discovered during routine gynecologic examination. Symptoms, when present, may include bleeding, discharge, or the sensation of a mass. These lesions are characteristically polypoid or pedunculated, varying in size but usually less than 5 cm, and are typically solitary, although multiple polyps may occur and are usually associated with pregnancy. Evidence supporting that these lesions are hormonally driven, benign, reactive proliferations include: (1) their occurrence during pregnancy, during which they can be multiple and after which they can spontaneously regress; (2) their association with hormonal replacement therapy in postmenopausal women; and (3) expression of estrogen and progesterone receptors by the constituent stromal cells. Incomplete excision or continued hormonal stimulation (e.g., pregnancy) may be associated with recurrence.1–6

Pathology

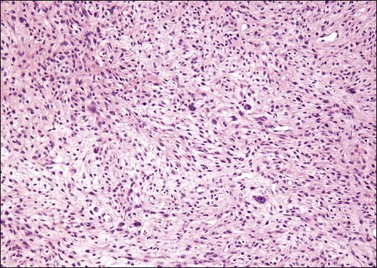

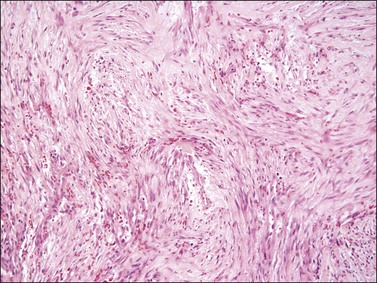

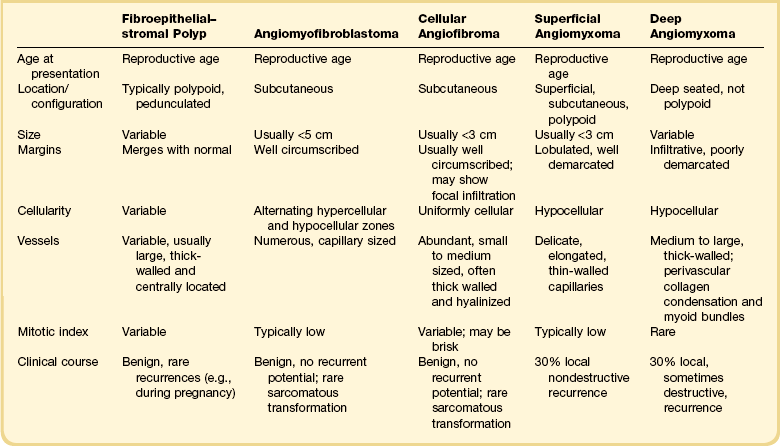

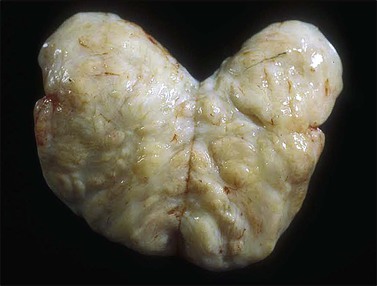

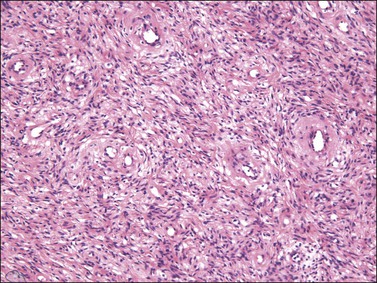

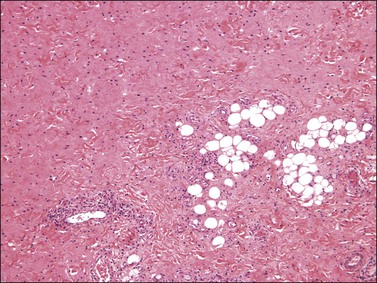

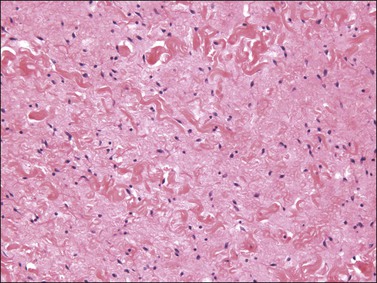

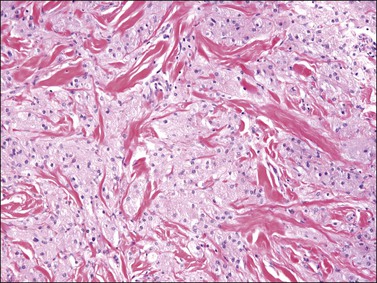

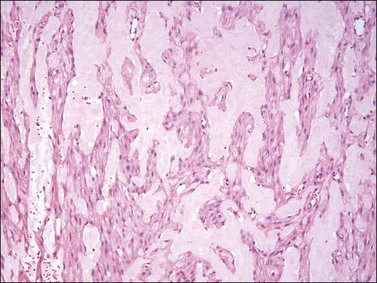

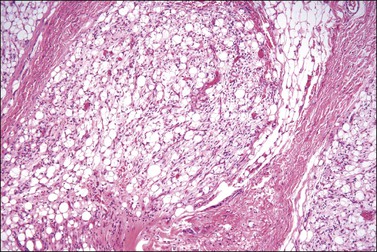

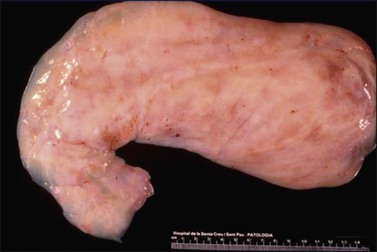

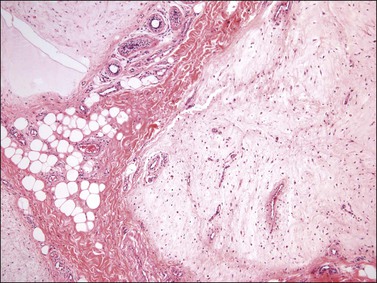

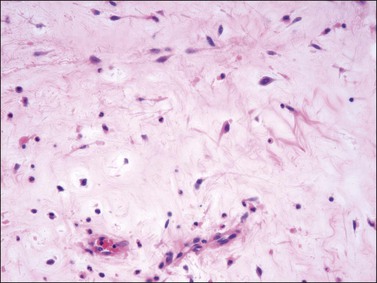

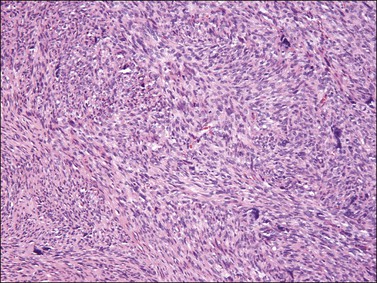

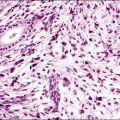

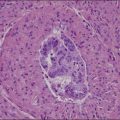

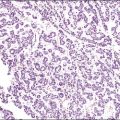

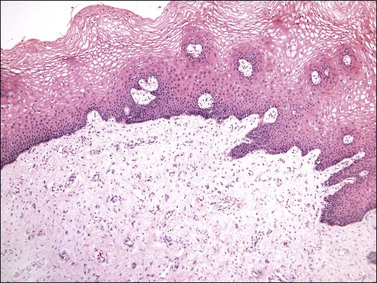

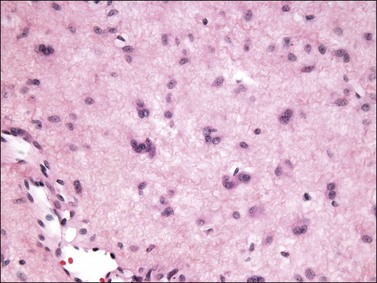

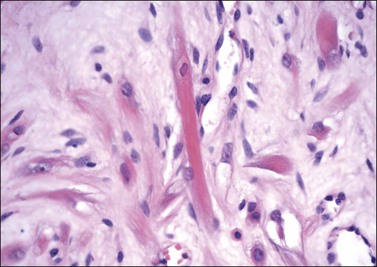

Gross examination typically reveals a polypoid mass with a central fibrovascular core covered by glistening squamous mucosa or skin (Figure 6.1). On occasion, multiple finger-like projections, which may clinically mimic a condyloma, are present. Histologically, these lesions exhibit: (1) a variably cellular spindle cell stroma most often located close to the surface epithelium with scattered stellate and multinucleate stromal cells; (2) a central fibrovascular core; and (3) overlying squamous epithelium or skin, which may exhibit varying degrees of hyperplasia (Figures 6.2 and 6.3).

Figure 6.1 Fibroepithelial–stromal polyp. Lesions are typically a polypoid/pedunculated mass. (Courtesy of Dr. J. R. Lewin, Jackson, MS.)

Figure 6.2 Fibroepithelial–stromal polyp. The lesion extends up to the epithelial interface without a clearly definable margin.

Figure 6.3 Fibroepithelial–stromal polyp. Characteristic appearance of the stellate and multinucleate stromal cells.

The stromal component has no clearly defined margin and extends up to the epithelial–submucosal interface. Similar to non-neoplastic vulvar stroma, the stromal cells of these polyps may be reactive for desmin, actin, vimentin, and estrogen and progesterone receptors. The most variable component of these lesions is the stroma, which may exhibit a significant degree of cellularity, nuclear pleomorphism, and mitotic activity, thereby mimicking a malignant process (Figure 6.4).7–10 These worrisome histologic features are particularly, but not invariably, present in polyps that occur during pregnancy (and account for the historical term ‘pseudosarcoma botryoides’).11

Differential Diagnosis

Pseudosarcomatous stromal polyps can be distinguished from a malignant process by the presence of stellate and multinucleate stromal cells near the epithelial–stromal interface, which are characteristically present in these polyps even in the most floridly pseudosarcomatous examples, and by the lack of an identifiable lesional margin. Fibroepithelial–stromal polyps are also readily distinguished from botryoid embryonal rhabdomyosarcoma as they are rare before puberty and lack both the characteristic hypercellular subepithelial (cambium) layer of sarcoma botryoides and specific markers of skeletal muscle differentiation.12

Nodular Fasciitis

Definition

A benign, self-limiting myofibroblastic neoplasm characterized by MYH9-USP6 gene fusion that shows rapid growth and spontaneous regression.13–16

Pathology

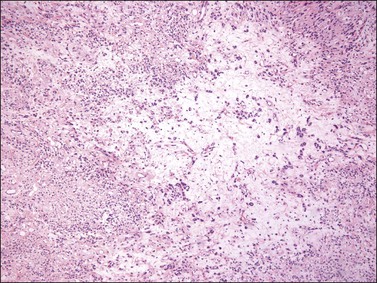

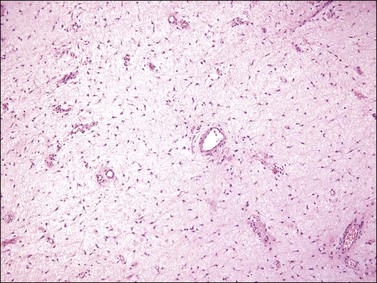

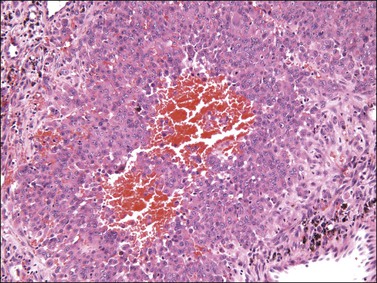

Similar to its counterparts elsewhere, nodular fasciitis involving the vulva is usually a well-circumscribed, unencapsulated mass that typically measures less than 3 cm in size. Histologically, it is a relatively well-circumscribed cellular proliferation of loosely arranged spindle cells set within a variably edematous or myxoid matrix that may exhibit microcystic change (Figure 6.5). The spindle cells, which are arranged in short interconnecting fascicles, have bipolar eosinophilic cytoplasmic processes with indistinct borders and ovoid nuclei with occasional nucleoli, imparting an overall appearance to the cells that has been likened to tissue culture fibroblasts. Scattered inflammatory cells, particularly lymphocytes, and extravasated red blood cells are commonly present. Osteoclast-like giant cells are also quite common. Immunohistochemically, the spindle cells are typically reactive for smooth muscle actin and negative for desmin. Nodular fasciitis is distinguished from a sarcoma, particularly leiomyosarcoma at this site, by the following: (1) lack of nuclear hyperchromasia or pleomorphism, (2) lack of necrosis, and (3) characteristic reactive ‘tissue culture’-like myofibroblastic growth pattern.

Benign Neoplasms

Angiomyofibroblastoma

Pathology

Tumors are typically small (usually <5 cm), well demarcated, tan/white and may have a rubbery consistency (Figure 6.6). They are composed of plump, round to ovoid or spindle-shaped cells, set within a variably edematous to collagenous matrix with alternating zones of cellularity (Figure 6.7). These cells, which have moderate amounts of eosinophilic cytoplasm and round nuclei with fine chromatin and inconspicuous nucleoli, characteristically cluster around the prominent vascular component, which is composed of numerous delicate, thin-walled capillaries (Figure 6.8). Tumor cells may be binucleate or appear somewhat epithelioid. Mitotic activity is typically sparse and occasional cases may have an adipocytic component. The spindle cells are typically reactive for desmin and negative for actin. In postmenopausal patients, lesional cells may be desmin negative.17–22

Differential Diagnosis

Angiomyofibroblastoma is distinguished from aggressive angiomyxoma by its well-circumscribed margin, its prominent vascular component (which is typically composed of smaller caliber vessels), and its alternating zones of cellularity. As both tumors share a similar immunophenotype, distinction is based on morphologic differences (Table 6.1).23

Cellular Angiofibroma

Clinical Features

Cellular angiofibroma is a rare benign stromal tumor that predominantly occurs in the vulva or perineum of middle-aged women (mean 54 years). Although initially described to occur exclusively at this site, they also occur in the inguinoscrotal region in men (so-called angiomyofibroblastoma-like tumor) and in extragenital sites (e.g., retroperitoneum, skin). In the vulva, they most commonly present as a relatively small (mean 2.7 cm) subcutaneous mass that is well circumscribed and painless. Cellular angiofibroma, if completely excised, behaves in a benign fashion with no recurrent potential. Incomplete excision may lead to regrowth of tumor; therefore, local excision with negative margins is adequate treatment. Very rare cases show sarcomatous transformation.24–29

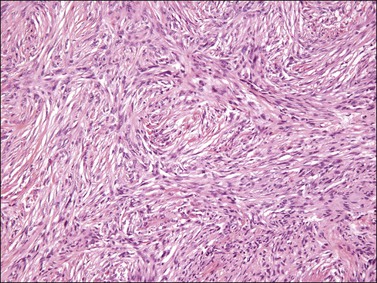

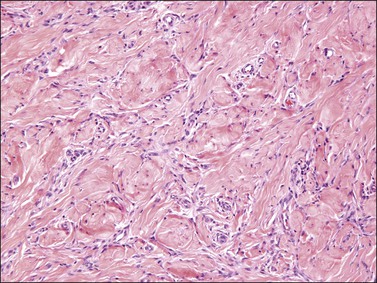

Pathology

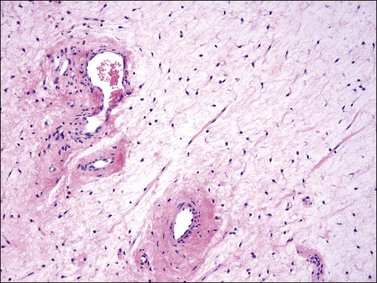

On gross examination, cellular angiofibroma typically is gray-white and has a firm, rubbery consistency (Figure 6.9). Histologically, it is usually well circumscribed; however, focal infiltration into surrounding soft tissue may be present. These tumors are characteristically cellular, composed of the following: (1) short, intersecting fascicles of bland, spindle-shaped cells with ovoid nuclei and scant palely eosinophilic cytoplasm; (2) numerous small to medium sized, thick-walled, and often hyalinized blood vessels; and (3) admixed wispy collagen bundles (Figure 6.10). In approximately 25% of cases, a usually minor component of adipose tissue is present. Mitotic activity, although brisk in some cases, is usually infrequent while necrosis and nuclear pleomorphism are typically absent. On occasion, atypia may be present, most commonly in the form of scattered hyperchromatic multinucleated cells (Figure 6.11). Rarely, abrupt transition to a discrete sarcomatous component can occur, which may exhibit features of atypical lipomatous tumor, pleomorphic liposarcoma or pleomorphic sarcoma, not otherwise specified.29 The spindle cells of cellular angiofibroma are reactive for CD34 in 60% of cases, and less commonly reactive for smooth muscle actin (20%) and desmin (8%). Half of all cases show reactivity for estrogen and progesterone receptors. Keratin, epithelial membrane antigen, and S-100 protein are negative.

Differential Diagnosis

Cellular angiofibroma is distinguished from a smooth muscle tumor by its more prominent vascular component, shorter fascicular growth pattern, and relative lack of eosinophilic cytoplasm. Distinction from angiomyofibroblastoma is based on its uniform cellularity; larger, thick-walled, and hyalinized blood vessels; and spindle cells arranged in short intersecting fascicles (Table 6.1).30 Mammary type myofibroblastoma and cellular angiofibroma are both well-circumscribed tumors composed of short intersecting fascicles of bland, CD34-positive spindle cells within a collagenous stroma; however, the vascular component of the former is typically not as prominent but can show a similar degree of hyalinization. These tumors both have similar genetic changes with loss of 13q14 (FOX1A1) and thus likely represent tumors along a spectrum exhibiting varied cellularity and vascularity.

Prepubertal Vulvar Fibroma

Definition

A poorly circumscribed, hypocellular lesion composed of bland spindle cells within a variably edematous, myxoid, or collagenous matrix that usually occurs in prepubertal girls.31–32

Pathology

Histologically, these tumors, which are located in submucosal or subcutaneous tissue, are poorly marginated with infiltration into surrounding tissue, including around adnexal structures and nerves, and into adipose tissue (Figure 6.12). In addition, there is no clear interface with the overlying epithelium. The lesion is hypocellular and composed of a patternless proliferation of bland, uniform spindle cells with ovoid nuclei and palely amphophilic cytoplasm set within a variably myxoid, edematous, or collagenous matrix (Figure 6.13). Small to medium sized vessels, some with mural thickening, are present. Mitotic activity is sparse and nuclear pleomorphism is absent. Lesional spindle cells are typically reactive for CD34 but are negative for smooth muscle actin, desmin, and S-100 protein.

Dermatofibroma (Fibrous Histiocytoma)

Clinical Features

Most commonly occurring on the limbs or trunk of adults, dermatofibroma occasionally involves vulvar skin. Although the clinical appearance is variable, most present as a flesh-colored papule, nodule, or plaque; however, some may be pigmented. The diagnosis may be suspected clinically by the presence of the so-called ‘dimpling’ sign; pinching of the tumor results in an inward dimpling of the lesion. Complete excision is usually not necessary unless the tumor shows unusual morphologic features (e.g., cellular, aneurysmal, plexiform, deeply infiltrative, or atypical variants) as these subtypes have locally recurrent potential. Following re-excision, very rare cases of these subtypes have been associated with regional lymph node or metastatic deposits in the lung; however, there are no morphologic indicators in the primary that would predict this biologic potential.33–43

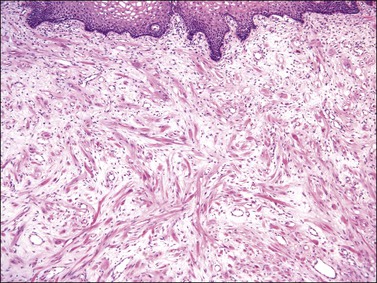

Pathology

Dermatofibroma exhibits a storiform proliferation of bland spindle cells with varying degrees of hyalinization of the dermal collagen, which is birefringent under polarized light (Figure 6.14). The tumor is relatively well circumscribed; however, entrapment of hyalinized bundles of dermal collagen by the spindle cells at the periphery of the tumor imparts a characteristic pseudoinfiltrative pattern (Figure 6.15). Another characteristic feature is the presence of overlying epidermal hyperplasia, which is common. A number of histologic variants are recognized (although these occur principally outside of the vulva) and include hemosiderotic, lipidized, aneurysmal (angiomatoid), atypical, epithelioid, plexiform, cellular, and deeply penetrating types. The spindle cells are often focally reactive for smooth muscle actin and negative for CD34, although the cellular variant may be reactive for CD34 at the periphery of the tumor. These lesions are often factor XIIIa positive, but most staining is in reactive dermal dendritic cells toward the periphery.33

Differential Diagnosis

Dermatofibroma can be distinguished from dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans, its main differential diagnostic consideration, by the following: (1) its lack of infiltration of adipose tissue (although this may be seen in the cellular and deeply penetrating variants), (2) presence of birefringent collagen under polarized light, (3) overlying epidermal hyperplasia, (4) tendency not to infiltrate around adnexal structures, and (5) lack of diffuse reactivity for CD34.43

Granular Cell Tumor

Clinical Features

Granular cell tumor is an uncommon neoplasm that typically arises in the skin and subcutaneous tissue of middle-aged adults with a slightly increased frequency in women. Tumors typically involve the head, neck, and trunk region, but may occasionally occur in the vulva, most often the labium majus. Patients usually present with a solitary, slowly growing, asymptomatic nodule that is often discovered incidentally on clinical examination. If present, symptoms may include pain, increased growth, and pruritus. Complete excision with clear margins is standard treatment, although these tumors seldom recur, even if incompletely excised. Malignant examples are rare.44–49

Pathology

Granular cell tumors are composed of strands and nests of polygonal cells with abundant eosinophilic granular cytoplasm and small, centrally placed, hyperchromatic nuclei separated by thin fibrous septa (Figure 6.16). Although distinctive, the characteristic granular cytoplasmic change, which is due to the accumulation of lysosomes, is not specific for this tumor type and may be seen in other types of neoplasms, such as smooth muscle tumors. Although many granular cell tumors are relatively well circumscribed, nearly half may show poorly defined or infiltrative margins. Nests of tumor cells adjacent to or surrounding small nerves are common. In addition, the tumor is often associated with overlying pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia, which may be mistaken for a squamous neoplasm if the underlying granular cell tumor is overlooked. Granular cell tumors are reactive for S-100 protein, neuron-specific enolase, CD68, and NKI-C3.

Leiomyoma

Clinical Features

Although genital smooth muscle tumors were initially considered within the category of superficial smooth muscle tumors, which includes pilar leiomyoma and angioleiomyoma, they are now classified separately based upon their differing clinical behavior, histologic features, and criteria for malignancy. Smooth muscle tumors of the distal female genitalia, unlike those of the uterus, are uncommon. They occur over a wide age range but are most common in the fourth and fifth decades and typically present as a painless, well-circumscribed mass usually <3 cm in size. Not uncommonly, the clinical impression is that of a cyst. Local excision for typical leiomyomas is adequate treatment. For tumors with unusual histologic features associated with recurrent potential (see the following sections), a margin of excision of at least 1 cm is recommended whenever possible, with close, long-term follow-up.50–55

Pathology

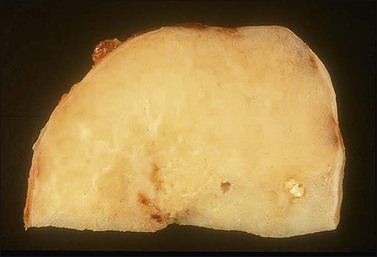

Similar to uterine smooth muscle tumors, vulvar leiomyomas usually exhibit the characteristic gross appearance of benign smooth muscle tumors of the myometrium but on occasion may have a more homogeneous appearance with less obvious whorling (Figure 6.17). In most instances, they are composed of intersecting fascicles of spindle-shaped cells with moderate amounts of eosinophilic cytoplasm and elongated, blunt-ended nuclei. However, an unusual morphologic pattern, which is commonly present in vulvar smooth muscle tumors, is the variable deposition of myxohyaline matrix, which imparts a plexiform or lacy appearance (Figure 6.18).

Figure 6.17 Leiomyoma. Well-circumscribed, tan/yellow mass with a homogeneous, glistening cut surface.

Lymphangioma Circumscriptum

Definition

An abnormality of dermal lymphatic channels exhibiting numerous dilated and cystic lymphatic spaces.56–60

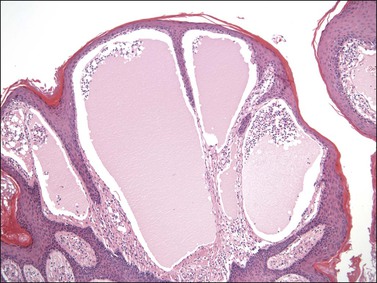

Pathology

Numerous dilated and cystic lymphatic channels are present, primarily within the papillary dermis, but also within the dermis and subcutaneous tissue. Those located in the papillary dermis are closely apposed to the overlying epithelium, which results in the clinical impression of a vesicle (Figure 6.19). Associated epidermal hyperplasia and a dermal lymphocytic infiltrate are common.

Angiokeratoma

Definition

A lesion composed of superficial ectatic vascular channels associated with epidermal hyperplasia.

Clinical Features

Angiokeratoma involving the vulva occurs over a wide age range, but typically presents before the sixth decade as an asymptomatic, red to purple, papular lesion under 1 cm in size. It often has a warty appearance due to associated epidermal changes. When present, symptoms include bleeding, pain, or pruritus. The lesion may be solitary or multiple, and if multiple should raise the possibility of Fabry disease, a rare X-linked chromosomal disorder of lipid metabolism in which there is a deficiency of lysosomal α-galactosidase.61–62

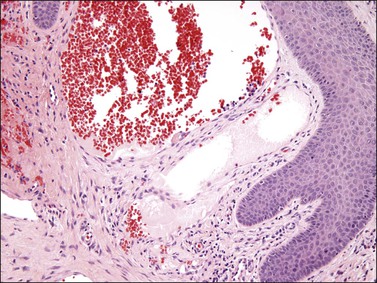

Pathology

Angiokeratoma exhibits closely apposed, dilated, blood-filled vascular spaces within the papillary dermis, partially surrounded by the overlying epithelium (Figure 6.20). The epithelium typically shows acanthosis, hyperkeratosis, and occasionally papillomatosis, resulting in the clinical impression of a warty lesion.

Other Rare Tumors

Vulvar leiomyomatosis54,63,64 is a rare condition in which patients have numerous, ill-defined, multinodular proliferations of smooth muscle involving the vulvar submucosa.

Genital rhabdomyoma65–67 most commonly involves the vagina of middle-aged women, but may occasionally occur in the vulva. Lesions are typically polypoid and patients usually present with bleeding or symptoms related to a mass. Histologically, this benign tumor exhibits a somewhat fascicular proliferation of well-differentiated rhabdomyoblasts within the submucosa (Figure 6.21). Cross-striations are usually easily identifiable (Figure 6.22).

Figure 6.21 Genital rhabdomyoma. Submucosal fascicular proliferation of well-differentiated rhabdomyoblasts.

Figure 6.22 Genital rhabdomyoma. Brightly eosinophilic cytoplasmic processes, some of which contain identifiable cross-striations.

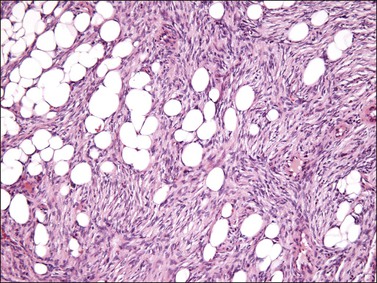

Lipoblastoma-like tumor of the vulva68 is a distinctive benign mesenchymal neoplasm that histologically resembles lipoblastoma in infants. In contrast to the latter, which typically occurs in the trunk and extremities of young boys under 5 years of age, this tumor occurs in young women. Histologically, the tumors are well circumscribed and composed of lobules of immature and mature adipocytes separated by thin fibrous septa resembling myxoid liposarcoma (Figure 6.23).

Locally Recurrent Neoplasms

Deep Angiomyxoma (Deep ‘Aggressive’ Angiomyxoma)

Clinical Features

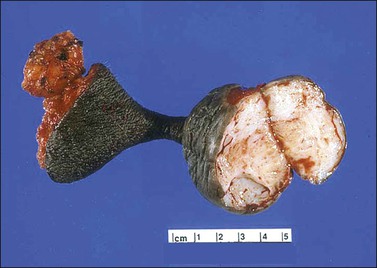

Deep angiomyxoma occurs principally in the pelvicoperineal region of reproductive age women, with a median incidence in the fourth decade, but rarely also develops in the inguinoscrotal region of men, in whom the median age at presentation is in the sixth to seventh decade. Often the clinical impression is that of a labial cyst, most commonly a Bartholin gland cyst. Tumors vary in size, but are often relatively large (>10 cm) and poorly marginated (Figure 6.24). Although there is a 20–30% risk of local, sometimes destructive recurrence, more than one recurrence is unusual and most are cured by an additional surgical excision with negative margins. Hence the currently preferred terminology is deep angiomyxoma, as these tumors are not as ‘aggressive’ as originally thought. Besides positive surgical margins, there are no clinical or histopathologic features that predict recurrent potential. Wide local excision with 1 cm margins is considered optimal and adequate treatment.

Pathology

Tumors typically have a gelatinous or myxoid appearance (Figure 6.25), but occasionally may appear more fibrous in a recurrence, presumably due to previous surgical scar tissue. Histologically, deep angiomyxoma is a poorly marginated, paucicellular neoplasm composed of uniformly distributed bland spindle cells with round to ovoid nuclei and moderate amounts of palely eosinophilic cytoplasm, discernible as bipolar or multipolar cell processes (Figure 6.26). The cells are set within a copious myxoid matrix that contains variably sized, but often medium to large, thick-walled, often hyalinized, blood vessels. Condensation of delicate fibrillary collagen around the blood vessels is characteristic, as is the presence of bundles of brightly eosinophilic smooth muscle cells (Figure 6.27). The spindle cells are typically reactive for desmin, smooth muscle actin, and estrogen and progesterone receptors, similar to normal vulvar mesenchyme. The spindle cells also can be positive for CD34, HMGA2, and CDK4. The expression of the last two markers is related to the fact that structural rearrangements of 12q15 with involvement of HMGA2, which encodes a factor important in transcriptional regulation, is the most frequent chromosomal aberration observed in deep (aggressive) angiomyxoma. Rearrangements appear to occur in approximately 30% of cases and the 12q15 breakpoint can be either intragenic or extragenic. Consequently, immunohistochemical expression of HMGA2 may only be useful in confirming the diagnosis or assessing margin status in a subset of cases.69–72

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis includes superficial angiomyxoma (see the following section), angiomyofibroblastoma, and an edematous fibroepithelial–stromal polyp (Table 6.1). Deep angiomyxoma is distinguished from angiomyofibroblastoma by its infiltrative margin, its vascular component (which is typically less prominent and composed of larger, thicker walled vessels), and its uniform paucicellularity. Deep angiomyxoma differs from edematous fibroepithelial–stromal polyps by its deep location, its infiltrative margin, its lack of polypoid superficial growth, and its uniformly bland cytomorphology with the lack of the characteristic stellate and multinucleate cells typical of stromal polyps.

Superficial Angiomyxoma (Cutaneous Myxoma)

Clinical Features

Superficial angiomyxoma usually involves the head, neck, and trunk region, but does occasionally occur in the vulva. It typically occurs in the fourth decade and patients usually present with a slowly growing, painless, polypoid mass that typically measures less than 5 cm in size. Although usually solitary, multiple lesions may be associated with Carney complex. Approximately one-third of these tumors recur locally if incompletely or marginally excised; therefore, complete excision with clear margins is recommended treatment.79–81

Pathology

Histologically, superficial angiomyxoma is a myxoid neoplasm with a distinctive multilobulated growth pattern that is centered in the dermis and superficial subcutaneous tissue (Figure 6.28). The relatively well-demarcated myxoid nodules contain slender spindle and stellate-shaped cells, delicate thin-walled capillaries, and scattered inflammatory cells, particularly polymorphonuclear leukocytes (Figure 6.29). The presence of acute inflammatory cells is not associated with necrosis or overlying epidermal ulceration and is presumably secondary to the production of a chemotactic factor by the tumor cells. In 10–20% of cases, an epithelial component—usually in the form of a squamous epithelial-lined cyst, buds of basaloid cells, or strands of squamous epithelium—is present, probably as a result of entrapped adnexal structures or stimulation of the overlying epithelium by the tumor. Immunohistochemically, the spindle cells are typically negative for actin, desmin, and S-100 protein.

Dermatofibrosarcoma Protuberans

Pathology

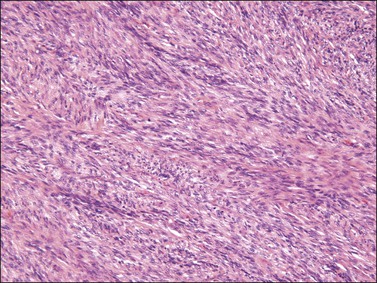

Histologically, the classic appearance of this tumor is that of a poorly circumscribed, storiform proliferation of uniform spindle cells involving the dermis and extending into subcutaneous adipose tissue in a characteristic lace-like or honeycomb pattern (Figure 6.30). A band of uninvolved dermis between the tumor and epidermis, which may be of normal thickness or atrophic, is typically present (Grenz zone). Entrapment of adnexal structures is common. In contrast to benign fibrous histiocytoma, polarizable collagen is typically absent. Some tumors, including those that occur in the vulva, may exhibit fibrosarcomatous change characterized by a herringbone, fascicular growth pattern with increased mitotic activity (Figure 6.31); tumors with this morphologic appearance have metastatic potential. Immunohistochemically, the neoplastic cells are typically diffusely reactive for CD34 and negative for factor XIIIa. Translocation between chromosomes 17 and 22, often in the form of supernumerary ring chromosomes, has been identified by cytogenetic analysis in this tumor type, including cases that have occurred in the vulva. This translocation results in the fusion of two genes, collagen type I α-1 (COL1A1) and platelet-derived growth factor β-chain (PDGFB).82–92

Malignant Neoplasms

Leiomyosarcoma

Pathology

Histologically, most vulvar leiomyosarcomas have a similar morphologic appearance to those that occur more commonly elsewhere in the female genital tract that are of the spindle cell type (Figure 6.32). Due to the rarity of these lesions, defining criteria to predict those tumors with metastatic potential remains problematic yet of paramount importance due to potential differences in clinical management. Use of the criteria proposed by Tavassoli and Norris55 is recommended, in which tumors with three or more of the following criteria should be diagnosed as leiomyosarcoma:

Although necrosis is excluded in this algorithm, its presence should strongly raise the possibility of malignancy.52–55,93–95

So-Called Proximal-Type Epithelioid Sarcoma

Pathology

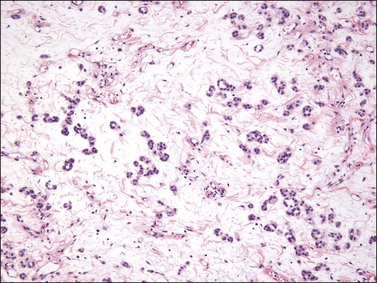

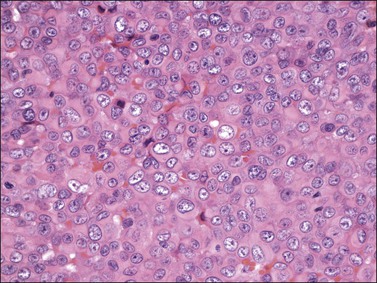

Histologically, this tumor exhibits a diffuse and often multinodular proliferation of relatively monomorphic large cells with abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm, imparting an epithelioid appearance. Rhabdoid inclusions are frequent (Figures 6.33 and 6.34). The tumor cells, which contain large vesicular nuclei and prominent nucleoli, commonly invade into subcutaneous or deeper soft tissue. Immunohistochemically, the tumor cells commonly react with keratin and epithelial membrane antigen. Approximately 50% express CD34 and may occasionally react for desmin and actin. The vast majority show loss of staining for INI1, the product of this ubiquitous chromatin remodeling gene located on chromosome 22q11.2, the expression of which is often lost in these tumors.96–100

Liposarcoma

Pathology

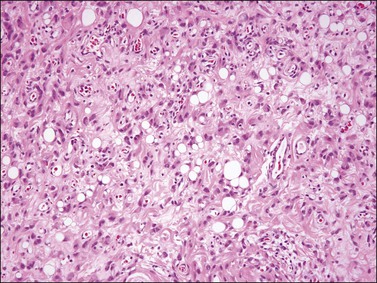

Histologically, most tumors have the usual morphologic appearance of well-differentiated liposarcoma/atypical lipomatous tumor with variation in adipocyte size, adipocytic nuclear atypia, cellular fibrous septa (often with scattered hyperchromatic stromal cells), and occasional lipoblasts. Some, however, may have an unusual morphology that is unique to tumors that arise at this site. These tumors show an admixture of neoplastic bland spindle and round cells, variably sized adipocytes, and numerous bivacuolated lipoblasts (Figure 6.35). This unusual morphology is not associated with any difference in behavior.101–104

References

1. Burt, RL, Prichard, RW, Kim, BS. Fibroepithelial polyp of the vagina. A report of five cases. Obstet Gynecol. 1976; 47:52S–54S.

2. Chirayil, SJ, Tobon, H. Polyps of the vagina: a clinicopathologic study of 18 cases. Cancer. 1981; 47:2904–2907.

3. Elliott, GB, Reynolds, HA, Fidler, HK. Pseudo-sarcoma botryoides of cervix and vagina in pregnancy. J Obstet Gynaecol Br Commonw. 1967; 74:728–733.

4. Hartmann, CA, Sperling, M, Stein, H. So-called fibroepithelial polyps of the vagina exhibiting an unusual but uniform antigen profile characterized by expression of desmin and steroid hormone receptors but no muscle-specific actin or macrophage markers. Am J Clin Pathol. 1990; 93:604–608.

5. Maenpaa, J, Soderstrom, KO, Salmi, T, Ekblad, U. Large atypical polyps of the vagina during pregnancy with concomitant human papilloma virus infection. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 1988; 27:65–69.

6. Miettinen, M, Wahlstrom, T, Vesterinen, E, Saksela, E. Vaginal polyps with pseudosarcomatous features. A clinicopathologic study of seven cases. Cancer. 1983; 51:1148–1151.

7. Mucitelli, DR, Charles, EZ, Kraus, FT. Vulvovaginal polyps. Histologic appearance, ultrastructure, immunocytochemical characteristics, and clinicopathologic correlations. Int J Gynecol Pathol. 1990; 9:20–40.

8. Norris, HJ, Taylor, HB. Polyps of the vagina. A benign lesion resembling sarcoma botryoides. Cancer. 1966; 19:227–232.

9. Nucci, MR, Fletcher, CD. Fibroepithelial stromal polyps of vulvovaginal tissue: from the banal to the bizarre. Pathol Case Rev. 1998; 3:151–157.

10. Nucci, MR, Young, RH, Fletcher, CD. Cellular pseudosarcomatous fibroepithelial stromal polyps of the lower female genital tract: an underrecognized lesion often misdiagnosed as sarcoma. Am J Surg Pathol. 2000; 24:231–240.

11. O’Quinn, AG, Edwards, CL, Gallager, HS. Pseudosarcoma botryoides of the vagina in pregnancy. Gynecol Oncol. 1982; 13:237–241.

12. Ostor, AG, Fortune, DW, Riley, CB. Fibroepithelial polyps with atypical stromal cells (pseudosarcoma botryoides) of vulva and vagina. A report of 13 cases. Int J Gynecol Pathol. 1988; 7:351–360.

13. Gaffney, EF, Majmudar, B, Bryan, JA. Nodular fasciitis (pseudosarcomatous fasciitis) of the vulva. Int J Gynecol Pathol. 1982; 1:307–312.

14. LiVolsi, VA, Brooks, JJ. Nodular fasciitis of the vulva: a report of two cases. Obstet Gynecol. 1987; 69:513–516.

15. Roberts, W, Daly, JW. Pseudosarcomatous fasciitis of the vulva. Gynecol Oncol. 1981; 11:383–386.

16. Erickson-Johnson, MR, Chou, MM, Evers, BR, et al. Nodular fasciitis: a novel model of transient neoplasia induced by MYH9-USP6 gene fusión. Lab Invest. 91, 2011. [1427–23].

17. Fletcher, CD, Tsang, WY, Fisher, C, et al. Angiomyofibroblastoma of the vulva. A benign neoplasm distinct from aggressive angiomyxoma. Am J Surg Pathol. 1992; 16:373–382.

18. Fukunaga, M, Nomura, K, Matsumoto, K, et al. Vulval angiomyofibroblastoma. Clinicopathologic analysis of six cases. Am J Clin Pathol. 1997; 107:45–51.

19. Hisaoka, M, Kouho, H, Aoki, T, et al. Angiomyofibroblastoma of the vulva: a clinicopathologic study of seven cases. Pathol Int. 1995; 45:487–492.

20. Laskin, WB, Fetsch, JF, Tavassoli, FA. Angiomyofibroblastoma of the female genital tract: analysis of 17 cases including a lipomatous variant. Hum Pathol. 1997; 28:1046–1055.

21. Nielsen, GP, Rosenberg, AE, Young, RH, et al. Angiomyofibroblastoma of the vulva and vagina. Mod Pathol. 1996; 9:284–291.

22. Nielsen, GP, Young, RH, Dickersin, GR, Rosenberg, AE. Angiomyofibroblastoma of the vulva with sarcomatous transformation (‘angiomyofibrosarcoma’). Am J Surg Pathol. 1997; 21:1104–1108.

23. Ockner, DM, Sayadi, H, Swanson, PE, et al. Genital angiomyofibroblastoma. Comparison with aggressive angiomyxoma and other myxoid neoplasms of skin and soft tissue. Am J Clin Pathol. 1997; 107:36–44.

24. Chen, E, Fletcher, CD. Cellular angiofibroma with atypia or sarcomatous transformation: clinicopathologic analysis of 13 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 2010; 34:707–714.

25. Flucke, U, van Krieken, JH, Mentzel, T. Cellular angiofibroma: analysis of 25 cases emphasizing its relationship to spindle cell lipoma and mammary-type myofibroblastoma. Mod Pathol. 2011; 24:82–89.

26. Iwasa, Y, Fletcher, CD. Cellular angiofibroma: clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical analysis of 51 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 2004; 28:1426–1435.

27. Laskin, WB, Fetsch, JF, Mostofi, FK. Angiomyofibroblastomalike tumor of the male genital tract: analysis of 11 cases with comparison to female angiomyofibroblastoma and spindle cell lipoma. Am J Surg Pathol. 1998; 22:6–16.

28. McCluggage, WG, Ganesan, R, Hirschowitz, L, et al. Cellular angiofibroma and related fibromatous lesions of the vulva: report of a series of cases with a morphological spectrum wider than previously described. Histopathology. 2004; 45:360–368.

29. McCluggage, WG, Perenyei, M, Irwin, ST. Recurrent cellular angiofibroma of the vulva. J Clin Pathol. 2002; 55:477–479.

30. Nucci, MR, Granter, SR, Fletcher, CD. Cellular angiofibroma: a benign neoplasm distinct from angiomyofibroblastoma and spindle cell lipoma. Am J Surg Pathol. 1997; 21:636–644.

31. Iwasa, Y, Fletcher, CD. Distinctive prepubertal vulval fibroma: a hitherto unrecognized mesenchymal tumor of prepubertal girls: analysis of 11 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 2004; 28:1601–1608.

32. Vargas, SO, Kozakewich, HP, Boyd, TK, et al. Childhood asymmetric labium majus enlargement: mimicking a neoplasm. Am J Surg Pathol. 2005; 29:1007–1016.

33. Abenoza, P, Lillemoe, T. CD34 and factor XIIIa in the differential diagnosis of dermatofibroma and dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans. Am J Dermatopathol. 1993; 15:429–434.

34. Calonje, E, Fletcher, CD. Aneurysmal benign fibrous histiocytoma: clinicopathological analysis of 40 cases of a tumour frequently misdiagnosed as a vascular neoplasm. Histopathology. 1995; 26:323–331.

35. Calonje, E, Mentzel, T, Fletcher, CD. Cellular benign fibrous histiocytoma. Clinicopathologic analysis of 74 cases of a distinctive variant of cutaneous fibrous histiocytoma with frequent recurrence. Am J Surg Pathol. 1994; 18:668–676.

36. Colome-Grimmer, MI, Evans, HL. Metastasizing cellular dermatofibroma. A report of two cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 1996; 20:1361–1367.

37. Franquemont, DW, Cooper, PH, Shmookler, BM, et al. Benign fibrous histiocytoma of the skin with potential for local recurrence: a tumor to be distinguished from dermatofibroma. Mod Pathol. 1990; 3:158–163.

38. Gonzalez, S, Duarte, I. Benign fibrous histiocytoma of the skin. A morphologic study of 290 cases. Pathol Res Pract. 1982; 174:379–391.

39. Iwata, J, Fletcher, CD. Lipidized fibrous histiocytoma: clinicopathologic analysis of 22 cases. Am J Dermatopathol. 2000; 22:126–134.

40. Kaddu, S, McMenamin, ME, Fletcher, CD. Atypical fibrous histiocytoma of the skin: clinicopathologic analysis of 59 cases with evidence of infrequent metastasis. Am J Surg Pathol. 2002; 26:35–46.

41. Requena, L, Aguilar, A, Lopez Redondo, MJ, et al. Multinodular hemosiderotic dermatofibroma. Dermatologica. 1990; 181:320–323.

42. Singh Gomez, C, Calonje, E, Fletcher, CD. Epithelioid benign fibrous histiocytoma of skin: clinico-pathological analysis of 20 cases of a poorly known variant. Histopathology. 1994; 24:123–129.

43. Zelger, B, Sidoroff, A, Stanzl, U, et al. Deep penetrating dermatofibroma versus dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans. A clinicopathologic comparison. Am J Surg Pathol. 1994; 18:677–686.

44. Haley, JC, Mirowski, GW, Hood, AF. Benign vulvar tumors. Semin Cutan Med Surg. 1998; 17:196–204.

45. Horowitz, IR, Copas, P, Majmudar, B. Granular cell tumors of the vulva. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1995; 173:1710–1713.

46. Kondi-Pafiti, A, Kairi-Vassilatou, E, Liapis, A, et al. Granular cell tumor of the female genital system. Clinical and pathologic characteristics of five cases and literature review. Eur J Gynaecol Oncol. 2010; 31:222–224.

47. Lack, EE, Worsham, GF, Callihan, MD, et al. Granular cell tumor: a clinicopathologic study of 110 patients. J Surg Oncol. 1980; 13:301–316.

48. Majmudar, B, Castellano, PZ, Wilson, RW, et al. Granular cell tumors of the vulva. J Reprod Med. 1990; 35:1008–1014.

49. Robertson, AJ, McIntosh, W, Lamont, P, et al. Malignant granular cell tumour (myoblastoma) of the vulva: report of a case and review of the literature. Histopathology. 1981; 5:69–79.

50. Guardiola, MT, Dobin, SM, Dal Cin, P, et al. Pericentric inversion (12)(p12q13-14) as the sole chromosomal abnormality in a leiomyoma of the vulva. Cancer Genet Cytogenet. 2010; 199:21–23.

51. Horton, E, Dobin, SM, Debiec-Rychter, M, et al. A clonal translocation (7;8)(p13;q11.2) in a leiomyoma of the vulva. Cancer Genet Cytogenet. 2006; 170:58–60.

52. Newman, PL, Fletcher, CD. Smooth muscle tumours of the external genitalia: clinicopathological analysis of a series. Histopathology. 1991; 18:523–529.

53. Nielsen, GP, Rosenberg, AE, Koerner, FC, et al. Smooth-muscle tumors of the vulva. A clinicopathological study of 25 cases and review of the literature. Am J Surg Pathol. 1996; 20:779–793.

54. Nucci, MR, Fletcher, CD. Vulvovaginal soft tissue tumours: update and review. Histopathology. 2000; 36:97–108.

55. Tavassoli, FA, Norris, HJ. Smooth muscle tumors of the vulva. Obstet Gynecol. 1979; 53:213–217.

56. Flanagan, BP, Helwig, EB. Cutaneous lymphangioma. Arch Dermatol. 1977; 113:24–30.

57. Peachey, RD, Lim, CC, Whimster, IW. Lymphangioma of skin. A review of 65 cases. Br J Dermatol. 1970; 83:519–527.

58. Prioleau, PG, Santa Cruz, DJ. Lymphangioma circumscriptum following radical mastectomy and radiation therapy. Cancer. 1978; 42:1989–1991.

59. Stewart, CJ, Chan, T, Platten, M. Acquired lymphangiectasia (‘lymphangioma circumscriptum’) of the vulva: a report of eight cases. Pathology. 2009; 41:448–453.

60. Vlastos, AT, Malpica, A, Follen, M. Lymphangioma circumscriptum of the vulva: a review of the literature. Obstet Gynecol. 2003; 101:946–954.

61. Cohen, PR, Young, AW, Jr., Tovell, HM. Angiokeratoma of the vulva: diagnosis and review of the literature. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 1989; 44:339–346.

62. Terzakis, E, Androutsopoulos, G, Zygouris, D, et al. Angiokeratoma of the vulva. Eur J Gynaecol Oncol. 2011; 32:597–598.

63. Faber, K, Jones, MA, Spratt, D, et al. Vulvar leiomyomatosis in a patient with esophagogastric leiomyomatosis: review of the syndrome. Gynecol Oncol. 1991; 41:92–94.

64. Miner, JH. Alport syndrome with diffuse leiomyomatosis. When and when not? Am J Pathol. 1999; 154:1633–1635.

65. Chabrel, CM, Beilby, JO. Vaginal rhabdomyoma. Histopathology. 1980; 4:645–651.

66. Hanski, W, Hagel-Lewicka, E, Daniszewski, K. Rhabdomyomas of female genital tract. Report on two cases. Zentralbl Pathol. 1991; 137:439–442.

67. Iversen, UM. Two cases of benign vaginal rhabdomyoma. Case reports. APMIS. 1996; 104:575–578.

68. Lae, ME, Pereira, PF, Keeney, GL, et al. Lipoblastoma-like tumour of the vulva: report of three cases of a distinctive mesenchymal neoplasm of adipocytic differentiation. Histopathology. 2002; 40:505–509.

69. Kazmierczak, B, Wanschura, S, Meyer-Bolte, K, et al. Cytogenic and molecular analysis of an aggressive angiomyxoma. Am J Pathol. 1995; 147:580–585.

70. McCluggage, WG, Patterson, A, Maxwell, P. Aggressive angiomyxoma of pelvic parts exhibits oestrogen and progesterone receptor positivity. J Clin Pathol. 2000; 53:603–605.

71. Medeiros, F, Erickson-Johnson, MR, Keeney, GL, et al. Frequency and characterization of HMGA2 and HMGA1 rearrangements in mesenchymal tumors of the lower genital tract. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2007; 46:981–990.

72. Micci, F, Panagopoulos, I, Bjerkehagen, B, et al. Deregulation of HMGA2 in an aggressive angiomyxoma with t(11;12)(q23;q15). Virchows Arch. 2006; 448:838–842.

73. Nucci, MR, Weremowicz, S, Neskey, DM, et al. Chromosomal translocation t(8;12) induces aberrant HMGIC expression in aggressive angiomyxoma of the vulva. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2001; 32:172–176.

74. Rabban, JT, Dal Cin, P, Oliva, E. HMGA2 rearrangement in a case of vulvar aggressive angiomyxoma. Int J Gynecol Pathol. 2006; 25:403–407.

75. Rawlinson, NJ, West, WW, Nelson, M, et al. Aggressive angiomyxoma with t(12;21) and HMGA2 rearrangement: report of a case and review of the literature. Cancer Genet Cytogenet. 2008; 181:119–124.

76. Steeper, TA, Rosai, J. Aggressive angiomyxoma of the female pelvis and perineum. Report of nine cases of a distinctive type of gynecologic soft-tissue neoplasm. Am J Surg Pathol. 1983; 7:463–475.

77. Tsang, WY, Chan, JK, Lee, KC, et al. Aggressive angiomyxoma. A report of four cases occurring in men. Am J Surg Pathol. 1992; 16:1059–1065.

78. van Roggen, JF, van Unnik, JA, Briaire-de Bruijn, IH, et al. Aggressive angiomyxoma: a clinicopathological and immunohistochemical study of 11 cases with long-term follow-up. Virchows Arch. 2005; 446:157–163.

79. Allen, PW, Dymock, RB, MacCormac, LB. Superficial angiomyxomas with and without epithelial components. Report of 30 tumors in 28 patients. Am J Surg Pathol. 1988; 12:519–530.

80. Calonje, E, Guerin, D, McCormick, D, et al. Superficial angiomyxoma: clinicopathologic analysis of a series of distinctive but poorly recognized cutaneous tumors with tendency for recurrence. Am J Surg Pathol. 1999; 23:910–917.

81. Fetsch, JF, Laskin, WB, Tavassoli, FA. Superficial angiomyxoma (cutaneous myxoma): a clinicopathologic study of 17 cases arising in the genital region. Int J Gynecol Pathol. 1997; 16:325–334.

82. Barnhill, DR, Boling, R, Nobles, W, et al. Vulvar dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans. Gynecol Oncol. 1988; 30:149–152.

83. Bock, JE, Andreasson, B, Thorn, A, et al. Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans of the vulva. Gynecol Oncol. 1985; 20:129–135.

84. Davos, I, Abell, MR. Soft tissue sarcomas of vulva. Gynecol Oncol. 1976; 4:70–86.

85. Ghorbani, RP, Malpica, A, Ayala, AG. Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans of the vulva: clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical analysis of four cases, one with fibrosarcomatous change, and review of the literature. Int J Gynecol Pathol. 1999; 18:366–373.

86. Gokden, N, Dehner, LP, Zhu, X, et al. Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans of the vulva and groin: detection of COL1A1-PDGFB fusion transcripts by RT-PCR. J Cutan Pathol. 2003; 30:190–195.

87. Leake, JF, Buscema, J, Cho, KR, et al. Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans of the vulva. Gynecol Oncol. 1991; 41:245–249.

88. Mentzel, T, Beham, A, Katenkamp, D, et al. Fibrosarcomatous (‘high-grade’) dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans: clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical study of a series of 41 cases with emphasis on prognostic significance. Am J Surg Pathol. 1998; 22:576–587.

89. Moodley, M, Moodley, J. Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans of the vulva: a case report and review of the literature. Gynecol Oncol. 2000; 78:74–75.

90. Naeem, R, Lux, ML, Huang, SF, et al. Ring chromosomes in dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans are composed of interspersed sequences from chromosomes 17 and 22. Am J Pathol. 1995; 147:1553–1558.

91. Soergel, TM, Doering, DL, O’Connor, D. Metastatic dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans of the vulva. Gynecol Oncol. 1998; 71:320–324.

92. Vanni, R, Faa, G, Dettori, T, et al. A case of dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans of the vulva with a COL1A1/PDGFB fusion identical to a case of giant cell fibroblastoma. Virchows Arch. 2000; 437:95–100.

93. Curtin, JP, Saigo, P, Slucher, B, et al. Soft-tissue sarcoma of the vagina and vulva: a clinicopathologic study. Obstet Gynecol. 1995; 86:269–272.

94. DiSaia, PJ, Rutledge, F, Smith, JP. Sarcoma of the vulva. Report of 12 patients. Obstet Gynecol. 1971; 38:180–184.

95. Nirenberg, A, Ostor, AG, Slavin, J, et al. Primary vulvar sarcomas. Int J Gynecol Pathol. 1995; 14:55–62.

96. Guillou, L, Wadden, C, Coindre, JM, et al. ‘Proximal-type’ epithelioid sarcoma, a distinctive aggressive neoplasm showing rhabdoid features. Clinicopathologic, immunohistochemical, and ultrastructural study of a series. Am J Surg Pathol. 1997; 21:130–146.

97. Hollmann, TJ, Hornick, JL. INI1-deficient tumors: diagnostic features and molecular genetics. Am J Surg Pathol. 2011; 35:e47–e63.

98. Kasamatsu, T, Hasegawa, T, Tsuda, H, et al. Primary epithelioid sarcoma of the vulva. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2001; 11:316–320.

99. Kim, HJ, Kim, MH, Kwon, J, et al. Proximal-type epithelioid sarcoma of the vulva with INI1 diagnostic utility. Ann Diagn Pathol. 2012; 16:411–415.

100. Tholpady, A, Lonergan, CL, Wick, MR. Proximal-type epithelioid sarcoma of the vulva: relationship to malignant extrarenal rhabdoid tumor. Int J Gynecol Pathol. 2010; 29:600–604.

101. Genton, CY, Maroni, ES. Vulval liposarcoma. Arch Gynecol. 1987; 240:63–66.

102. Gondos, B, Casey, MJ. Liposarcoma of the perineum. Gynecol Oncol. 1982; 14:133–140.

103. Nucci, MR, Fletcher, CD. Liposarcoma (atypical lipomatous tumors) of the vulva: a clinicopathologic study of six cases. Int J Gynecol Pathol. 1998; 17:17–23.

104. Vecchione, A, Palazzetti, P. [Anatomoclinical considerations on a case of liposarcoma with vulvar localization]. Riv Anat Pathol Oncol. 1967; 31:177–193.

105. Copeland, LJ, Gershenson, DM, Saul, PB, et al. Sarcoma botryoides of the female genital tract. Obstet Gynecol. 1985; 66:262–266.

106. Copeland, LJ, Sneige, N, Stringer, CA, et al. Alveolar rhabdomyosarcoma of the female genitalia. Cancer. 1985; 56:849–855.

107. Imachi, M, Tsukamoto, N, Kamura, T, et al. Alveolar rhabdomyosarcoma of the vulva. Report of two cases. Acta Cytol. 1991; 35:345–349.

108. Shen, JT, D’Ablaing, G, Morrow, CP. Alveolar soft part sarcoma of the vulva: report of first case and review of literature. Gynecol Oncol. 1982; 13:120–128.

109. Cetiner, H, Kir, G, Gelmann, EP, et al. Primary vulvar Ewing sarcoma/primitive neuroectodermal tumor: a report of 2 cases and review of the literature. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2009; 19:1131–1136.

110. McCluggage, WG, Sumathi, VP, Nucci, MR, et al. Ewing family of tumours involving the vulva and vagina: report of a series of four cases. J Clin Pathol. 2007; 60:674–680.

111. Hall, DJ, Burns, JC, Goplerud, DR. Kaposi’s sarcoma of the vulva: a case report and brief review. Obstet Gynecol. 1979; 54:478–483.

112. Macasaet, MA, Duerr, A, Thelmo, W, et al. Kaposi sarcoma presenting as a vulvar mass. Obstet Gynecol. 1995; 86:695–697.