Chapter 537 Voiding Dysfunction

Diurnal Incontinence

Daytime incontinence not secondary to neurologic abnormalities is common in children (Chapter 21.3). At age 5 yr, 95% have been dry during the day at some time and 92% are dry. At 7 yr, 96% are dry, although 15% have significant urgency at times. At 12 yr, 99% are dry during the day. The most common cause of daytime incontinence is an overactive bladder. Table 537-1 lists the causes of diurnal incontinence in children.

Important points in the history include the pattern of incontinence, including the frequency, the volume of urine lost during incontinent episodes, whether the incontinence is associated with urgency or giggling, whether it occurs after voiding, and whether the incontinence is continuous. The frequency of voiding and whether there is nocturnal enuresis, a strong, continuous urinary stream, or sensation of incomplete bladder emptying should be assessed. A diary of when the child voids and whether the child was wet or dry is helpful. Other urologic problems such as urinary tract infections (UTIs), reflux, neurologic disorders, or a family history of duplication anomalies should be assessed. Bowel habits also should be evaluated, because incontinence is common in children with constipation and/or encopresis. Diurnal incontinence can occur in girls with a history of sexual abuse. Physical examination is directed at identifying signs of organic causes of incontinence: short stature, hypertension, enlarged kidneys and/or bladder, constipation, labial adhesion, ureteral ectopy, back or sacral anomalies (see Fig. 536-4), and neurologic abnormalities.

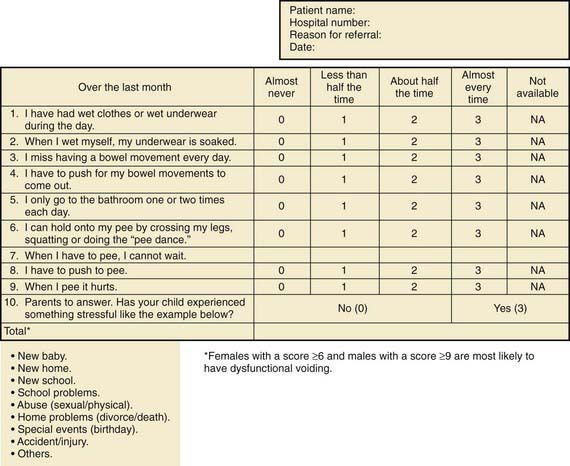

Assessment tools include urinalysis, with culture if indicated; bladder diary (recorded times and volumes voided, whether wet or dry); postvoid residual urine volume (generally obtained by bladder scan); Dysfunctional Voiding Symptom Score (Fig. 537-1); Bristol Stool Form Score (Fig. 537-2); and uroflow with or without EMG (noninvasive assessment of urinary flow pattern and measurement of external sphincter activity). Imaging is performed in children who have significant physical findings, a family history of urinary tract anomalies or UTIs, and those who do not respond to therapy appropriately. A renal ultrasonogram with or without a voiding cystourethrogram (VCUG) is indicated. Urodynamics should be performed if there is evidence of neurologic disease and may be helpful if empirical therapy is ineffective.

Overactive Bladder

Children with an overactive bladder typically exhibit urinary frequency, urgency, and urge incontinence. Often a girl will squat down on her foot to try to prevent incontinence (termed Vincent’s curtsy). The bladder in these children is functionally, but not anatomically, smaller than normal and exhibits strong uninhibited contractions. Approximately 25% of children with nocturnal enuresis also have symptoms of an overactive bladder. Many children indicate they do not feel the need to urinate, even just before they are incontinent. In girls, a history of recurrent UTI is common, but incontinence can persist long after infections are brought under control. It is not clear in these cases if the voiding dysfunction is a sequela of the UTIs or if the voiding dysfunction predisposes to recurrent UTIs. In girls, voiding cystourethrography often shows a dilated urethra (“spinning top deformity,” Fig. 537-3) and narrowed bladder neck with bladder wall hypertrophy. The urethral finding results from inadequate relaxation of the external urinary sphincter. Constipation is common and should be treated, particularly with any child with Bristol Stool Score 1 or 2.

Non-Neurogenic Neurogenic Bladder (Hinman Syndrome)

Hinman syndrome is a more serious but less common disorder involving failure of the external sphincter to relax during voiding in children without neurologic abnormalities. Children with this syndrome, also called detrusor-sphincter dyssynergia, typically exhibit a staccato stream, day and night wetting, recurrent UTIs, constipation, and encopresis. Evaluation of affected children often reveals vesicoureteral reflux, a trabeculated bladder, and a decreased urinary flow rate with an intermittent pattern (Fig. 537-4). In severe cases, hydronephrosis, renal insufficiency, and even end-stage renal disease can occur. The pathogenesis of this syndrome is thought to involve learning abnormal voiding habits during toilet training; the syndrome is rarely seen in infants. Urodynamic studies and magnetic resonance imaging of the spine are indicated to rule out a neurologic cause for the bladder dysfunction.

Vaginal Voiding

In girls with vaginal voiding, incontinence typically occurs after urination after the girl stands up. Usually the volume of urine is 5-10 mL. One of the most common causes is labial adhesion (see Fig. 537-5). This lesion is seen in young girls and can be managed either by topical application of estrogen cream to the adhesion or lysis in the office. Some girls experience vaginal voiding because they do not separate their legs widely during urination. These girls either are overweight or do not pull their underwear down to their ankles when they urinate. Management involves encouraging the girl to separate the legs as widely as possible during urination. The most effective way to do this is to have the child sit backward on the toilet seat during micturition.

Other Causes of Incontinence in Girls

Ureteral ectopia, usually associated with a duplicated collecting system in girls, refers to a ureter that drains outside the bladder, often into the vagina or distal urethra. It can produce urinary incontinence characterized by constant urinary dripping all day, even though the child voids regularly. Sometimes the urine production from the renal segment drained by the ectopic ureter is small, and urinary drainage is confused with watery vaginal discharge. Children with a history of vaginal discharge or incontinence and an abnormal voiding pattern require careful study. The ectopic orifice usually is difficult to find. On ultrasonography or intravenous urography, one may suspect duplication of the collecting system (Fig. 537-6), but the upper collecting system drained by the ectopic ureter usually has poor or delayed function. CT scanning of the kidneys or an MR urogram should demonstrate subtle duplication anomalies. Examination under anesthesia for an ectopic ureteral orifice in the vestibule or the vagina may be necessary (Fig. 537-7). The treatment in these cases is either partial nephrectomy, with removal of the upper pole segment of the duplicated kidney and its ureter down to the pelvic brim, or ipsilateral ureteroureterostomy, in which the upper pole ectopic ureter is anastomosed to the normally positioned lower pole ureter. These procedures often are performed by minimally invasive laparoscopy with or without robotic assistance.

Total incontinence in girls may be secondary to epispadias (Fig. 535-2). This condition, which affects only 1 of 480,000 females, is characterized by separation of the pubic symphysis, separation of the right and left sides of the clitoris, and a patulous urethra (Chapter 535). Treatment is bladder neck reconstruction or placement of an artificial urinary sphincter to repair the incompetent urethra.

Nocturnal Enuresis

By 5 yr of age, 90-95% of children are nearly completely continent during the day, and 80-85% are continent at night. Nocturnal enuresis (Chapter 21.3) refers to the occurrence of involuntary voiding at night after 5 yr, the age when volitional control of micturition is expected. Enuresis may be primary (estimated 75-90% of children with enuresis; nocturnal urinary control never achieved) or secondary (10-25%; the child was dry at night for at least a few months and then enuresis developed). In addition, 75% of children with enuresis are wet only at night, and 25% are incontinent day and night. This distinction is important, because children with both forms are more likely to have an abnormality of the urinary tract.

Pathogenesis

The pathogenesis of nocturnal enuresis (normal daytime voiding habits) is multifactorial (Table 537-2).

Table 537-2 NOCTURNAL ENURESIS

CAUSES

OTHER FEATURES

Clinical Manifestations and Diagnosis

A careful history should be obtained, especially with respect to fluid intake at night and pattern of nocturnal enuresis. Children with diabetes insipidus (Chapter 552), diabetes mellitus (Chapter 583), and chronic renal disease (Chapter 529) can have a high obligatory urinary output and a compensatory polydipsia. The family should be asked whether the child snores loudly at night. A complete physical examination should include palpation of the abdomen and rectal examination after voiding to assess the possibility of a chronically distended bladder. The child with nocturnal enuresis should be examined carefully for neurologic and spinal abnormalities. There is an increased incidence of bacteriuria in enuretic girls, and, if found, it should be investigated and treated (Chapter 532), although this does not always lead to resolution of bed-wetting. A urine sample should be obtained after an overnight fast and evaluated for specific gravity or osmolality to exclude polyuria as a cause of frequency and incontinence and to ascertain that the concentrating ability is normal. The absence of glycosuria should be confirmed. If there are no daytime symptoms, the physical examination and urinalysis are normal, and the urine culture is negative, further evaluation for urinary tract pathology generally is not warranted. A renal ultrasonogram is reasonable in an older child with enuresis or in children who do not respond appropriately to therapy.

Allen HA, Austin JC, Boyt HA, et al. Initial trial of timed voiding is warranted for all children with daytime incontinence. Urology. 2007;69:962-965.

Austin PF, Ferguson G, Yan Y, et al. Combination therapy with desmopressin and an anticholinergic medication for nonresponders to desmopressin for monosymptomatic nocturnal enuresis: randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Pediatrics. 2008;122:1027-1032.

Berry AK, Zderic S, Carr M. Methylphenidate for giggle incontinence. J Urol. 2009;182:2028-2032.

Drzewiecki BA, Kelly PR, Marinaccio B, et al. Biofeedback training for lower urinary tract symptoms: factors affecting efficacy. J Urol. 2009;182:2050-2055.

Fonseca EG, Bordallo APN, Garcia PK, et al. Lower urinary tract symptoms in enuretic and nonenuretic children. J Urol. 2009;182:1978-1983.

Glazener CM, Evans JH, Peto RE: Alarm interventions for nocturnal enuresis in children, Cochrane Database Syst Rev (2):CD002911, 2005.

Kamperis K, Hagstroem S, Rittig S, et al. Combination of the enuresis alarm and desmopressin. Second line treatment for enuresis nocturna. J Urol. 2008;179:1128-1131.

Nevéus T, Eggert P, Evans J, et al. Evaluation of and treatment for monosymptomatic enuresis: a standardization document from the International Children’s Continence Society. J Urol. 2010;183(2):441-447.

Neveus T, Tullus K. Tolterodine and imipramine in refractory enuresis: a placebo-controlled crossover study. Pediatr Nephrol. 2008;23:263-267.

Neveus T, von Gontard A, Hoebeke P, et al. The standardisation of terminology of lower urinary tract function in children and adolescents: Report from the Standardisation Committee of the International Children’s Continence Society (ICCS). J Urol. 2006;176:314-324.

Robson WLM. Evaluation and management of enuresis. New Engl J Med. 2009;360:1429-1436.

Sreedhar B, Yeung CK, Leung VY, et al. Ultrasound bladder measurements in children with severe primary nocturnal enuresis: pretreatment and posttreatment evaluation and its correlation with treatment outcome. J Urol. 2008;179:1568-1572.