CHAPTER 54 Voiding difficulty

Introduction

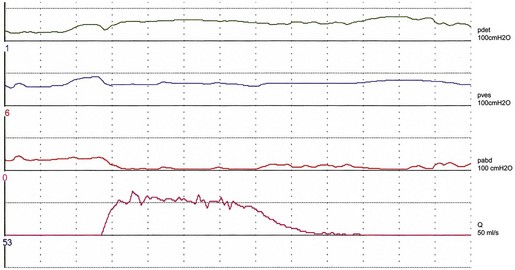

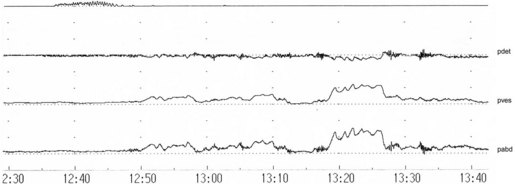

Studies on detrusor pressure during voiding in normal women suggest that most void with a detrusor contraction greater than 15 cmH2O (mean detrusor pressure at maximum flow 23–28 cmH2O, maximum detrusor pressure 20–36 cmH2O) (Figure 54.1). Detrusor pressure during voiding is generally lower in women than in men. A few normal women have been reported to void with a low pressure detrusor contraction of less than 15 cmH2O, but no normal women void with no contraction at all; such an event may indicate low urethral closure pressure.

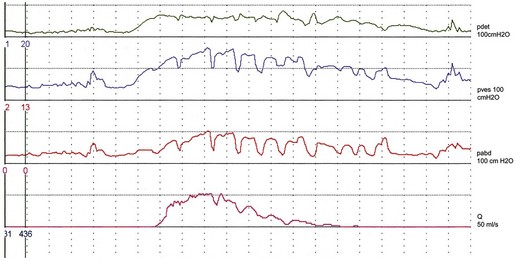

There are variations in the way that women void. Some women, in addition to pelvic relaxation and detrusor contraction, may strain by an unconscious but sustained Valsalva manoeuvre (Figure 54.2). The contribution of abdominal pressure to the voiding process varies considerably between individuals and within the same individual during consecutive voids.

The ‘normal’ voiding curve in women has a single peak, with a fast crescendo and a relatively slow diminuendo, with minimal fluctuations. However, an interrupted pattern can be seen repeatedly in a minority of normal women. Studies of flow rates suggest that most normal women void with a peak flow rate greater than 15 ml/s, with mean values of 23–27 ml/s (Figure 54.1). Peak flow rate values are generally higher in women than in men. The main variable affecting flow rates in normal women is bladder volume, with greater flow rates seen with increasing volumes. Parity, weight and height have no influence on flow rates.

Definitions

Voiding difficulty

A joint International Urogynecological Association/International Continence Society (ICS) Report on terminology for female pelvic floor dysfunction defines ‘voiding difficulty’ as ‘abnormally slow and/or incomplete micturition’ (Haylen et al 2010). The diagnosis is obtained by symptoms (see below) and urodynamic investigations, and should be based on repeated measurements to confirm abnormality.

Abnormally slow urine flow rates, as determined by uroflowmetry, are best referenced to nomogram charts which provide a range of normality for urinary flow rates in relation to volume voided; abnormal flow is defined as flow under the 10th centile (Haylen et al 1989). To encourage the use of these charts, a larger version of the original charts has been republished recently (Haylen et al 2008a).

Abnormally high postvoid residuals (i.e. volume left in the bladder at the completion of micturition) depend on the method used for measurement and the timing of the measurement after micturition, taking into account renal input of 1–14 ml urine/min (Haylen et al 2010).

Upper limits of postvoid residuals of 30 ml (using immediate ultrasound assessment) and 50–100 ml (using urethral catheterization) have been proposed (Haylen et al 2010).

Incidence

Depending on definition and type of clinic, voiding difficulty in women presenting to a urology or urogynaecology clinic has a variable prevalence ranging from 14% (when using a strict definition based on multiple variables including low flow, high pressure and increased postvoid residual) (Massey and Abrams 1988) to 39% (using a postvoid residual of 30 ml or more) (Haylen et al 2007).

Symptoms and Clinical Effects

Inability to void usually leads to prolonged use of urinary catheters and an increased incidence of UTI. The risk of acquiring bacteriuria relates to the duration of catheterization, and ranges from 4% to 7.5%/day over the first 10 days of catheterization (Schaeffer 1986). The majority of patients on long-term clean catheterization have bacteriuria, and about one-third of them require intermittent treatment with antibiotics due to symptomatic infection (Lapides et al 1976). Catheter-related UTI is an important cause of hospital-acquired infections, morbidity (e.g. pyelonephritis) and, in the elderly, mortality.

Causes

The causes of voiding difficulty are shown in Box 54.1.

Effects of age on voiding function

The incidence of voiding dysfunction in women increases with age (Haylen et al 2008b), and the process of ageing may decrease detrusor contractility and increase urethral rigidity.

Urodynamic studies have shown that both peak flow rate and detrusor pressure during voiding decrease with advancing age. Older women are also more likely to strain abdominally during voiding and to have higher residual urine volumes (Malone-Lee and Wahedna 1993).

It is not clear whether the menopause has an effect on voiding which is distinct from age. There are no studies showing that the menopause per se has a deleterious effect on voiding function. However, the distal urethra is oestrogen dependent and therefore susceptible to postmenopausal atrophic changes; the reduction in urethral functional length seen after the menopause is likely to be a manifestation of this process. There is evidence that these changes are more pronounced in a minority (18%) of postmenopausal women (Smith 1972). These women may have increased urethral rigidity and may be predisposed to the development of voiding dysfunction should they undergo pelvic or anti-incontinence surgery.

Postoperative voiding dysfunction

Pelvic surgery

With regards to specific procedures, clinical and urodynamic studies have found no evidence of increased voiding dysfunction in the short term after vaginal hysterectomy with anterior colporrhaphy performed at the same time (Stanton et al 1982), and after abdominal hysterectomy (Wake 1980). Also, no differences in bladder function were observed in a randomized study comparing total with subtotal hysterectomy (Thakar et al 2002). However, a history of previous hysterectomy has been associated with increased risk of voiding difficulty, possibly due to nerve dysfunction (Dietz et al 2002).

Extensive pelvic surgery might lead to denervation and prolonged or permanent voiding difficulty. Radical hysterectomy has been shown to lead to prolonged voiding difficulty in one-quarter of patients (Scotti et al 1986) due to neuropathic dysfunction.

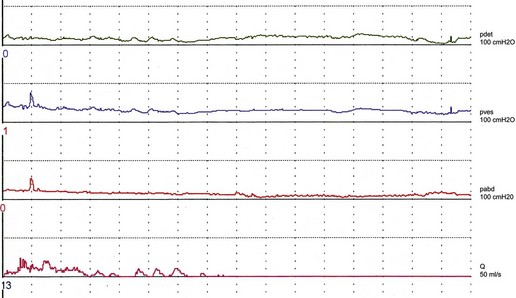

Surgery for stress incontinence

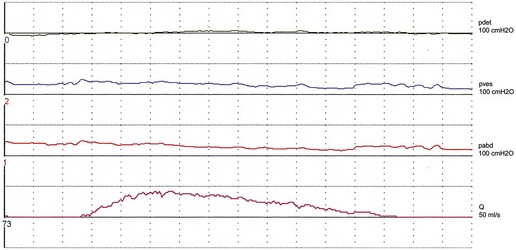

Women with stress incontinence may already have some impairment of voiding function, which may make them more vulnerable to the obstructive effects of surgery. This is suggested by differences in several urodynamic (voiding) variables noted in these women. For example, in contrast with normal women, women with stress incontinence are more likely to strain during voiding, and to initiate voiding with a Valsalva manoeuvre as opposed to pelvic relaxation. They also void with significantly lower detrusor pressures, and up to 15% have been shown to void without a contraction (Figure 54.3; Karram et al 1997). It is not clear whether this is due to the lower mean urethral pressure of women with urodynamic stress incontinence, or whether there is a real impairment of detrusor muscle function in these women.

Postoperative voiding disorders have been reported to occur after most operations for stress incontinence. Prolonged voiding dysfunction is uncommon after urethral injectables, although an incidence of 5% has been reported (Khullar et al 1997). The colposuspension operation leads to postoperative voiding dysfunction in a mean of 12.5% of patients (Jarvis 1994). Laparoscopic and open colposuspension have the same incidence of postoperative voiding difficulty (Carey et al 2006). Results of a randomized study comparing the tension-free vaginal tape (TVT) procedure with colposuspension suggest that the incidence of voiding difficulty at 6 months is similar after both operations (7%), although patients experience earlier voiding in the immediate postoperative period after the TVT procedure (Ward and Hilton 2002). After the TVT procedure, 11% of women have been reported to need a catheter for more than 24 h (Vervest et al 2007), with only 2% needing tape release for prolonged difficulty (Kuuva and Nilsson 2002, Karram et al 2003, Vervest et al 2007). The transobturator tape (TOT) procedure has been shown to have a lower incidence of postoperative voiding difficulty than the TVT, possibly as it is less obstructive (Latthe et al 2007).

Prolapse surgery

Short-term voiding difficulty is common after vaginal surgery for prolapse. In a large series of women undergoing such surgery, urinary retention (defined as a postvoid residual of ≥200 ml after removal of the catheter the day after the operation) occurred in 29% of women, with 9% experiencing retention for more than 3 days (Hakvoort et al 2009). In another study, 11% of women required catheterization at home after discharge from hospital (Vierhout 1998). However, no patients experienced long-term voiding difficulty (Vierhout 1998, Hakvoort et al 2009). Performing a levator muscle plication (as part of a posterior colporrhaphy) and a Kelly suburethral plication (as part of an anterior colporrhaphy) can increase the risk of postoperative retention (Hakvoort et al 2009).

A policy of early catheter removal, the day after vaginal surgery seems preferable to routine prolonged catheterization (4 days) as it is associated with a lower incidence of UTI and a shorter duration of hospital stay (Hakvoort et al 2004). However, early catheter removal increases the risk of recatheterization: 40% in the ‘early’ removal group vs 9% in the ‘late’ removal group (Hakvoort et al 2004). Prolonged catheterization may therefore be preferable in individual cases when there is an increased risk of postoperative voiding difficulty.

Postpartum voiding difficulty

Prolonged voiding difficulty in the postpartum period requiring self-catheterization is uncommon and has been reported to occur after less than 1% of deliveries (Glavind and Bjørk 2003). However, when using strict criteria [similar to those proposed recently by the International Urogynecological Association/International Continence Society (2010)], up to 43% of women have been shown to have some degree of voiding difficulty after delivery (Ramsay and Torbet 1993). Recognized risk factors for voiding difficulty in the immediate postpartum period are primiparity, instrumental delivery, epidural analgesia, prolonged labour, perineal trauma and poor bladder management resulting in overdistension. In addition to temporary factors (e.g. epidural, morphine, anaesthetic), other factors causing prolonged voiding dysfunction may be present (e.g. trauma to the bladder, pelvic floor muscles and nerves).

Neurological disease

Specific neurological conditions are discussed below.

Lumbar intervertebral disc prolapse

Lumbar disc prolapse is extremely common, with approximately 30% of adults without back pain having evidence of a protruded disc on magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) (Jarvik and Deyo 2007). In patients with symptomatic lumbar disc prolapse, urodynamic studies have shown voiding difficulty due to reduced detrusor contractility in approximately one-quarter of cases (Bartolin et al 1998). The most common sites of lumbar disc prolapse are L4–5 and L5–S1. Compression occurs more often in a posterolateral direction but may also be central. Patients may report a long history of low back pain, or voiding difficulty may be the first or only symptom. Compression of the sacral nerves can lead to cauda equina syndrome, characterized by voiding difficulty, saddle anaesthesia, bilateral sciatica and low back pain. Physical examination in these cases shows reduced sensation in the saddle and perianal area. If nerve compression is seen on MRI, urgent surgical treatment, usually laminectomy, is indicated. Despite this, voiding function often fails to improve after surgery (Bartolin et al 1999).

The lithotomy position commonly used to perform gynaecological procedures can potentially precipitate lumbar disc prolapse (Choudhari et al 2000). It has been suggested that flexion and hyperabduction of the hips may stretch nerve roots already compromised by a partial ‘occult’ disc prolapse (Choudhari et al 2000). When no other explanation can be found, this possibility should always be considered and investigated by MRI should a patient develop prolonged voiding difficulty after a gynaecological procedure.

Diabetes

Bladder dysfunction is relatively common in diabetic women and has been reported in 22% of women attending a diabetic clinic (Yu et al 2004). It is due to peripheral and autonomic neuropathy, leading to reduced bladder sensation and contractility. The classical features of diabetic cystopathy are an insidious onset with impaired bladder sensation and progressive voiding difficulty. Recurrent UTIs are common. Detrusor overactivity also occurs frequently, perhaps as a sign of cortical or spinal involvement.

Idiopathic bladder neck obstruction

This is a poorly defined, infrequent condition characterized by failure of the urethral sphincter to relax, and possibly hypertrophy, with urodynamic variables showing high pressure and low flow in the absence of neurological or urological abnormality. It was originally described in a cohort of young women with polycystic ovaries and voiding difficulty (Fowler’s syndrome; Fowler et al 1988). The cause is unknown. There is a suggestion that α-blockers may be beneficial in these patients (Athanasopoulos et al 2009).

Pelvic organ prolapse

Although the majority of women with pelvic organ prolapse (POP) can void effectively, there is an association between POP and voiding dysfunction (Coates et al 1997, Haylen et al 2008b). Symptoms of voiding difficulty (Digesu et al 2005) and high postvoid residuals (Haylen et al 2008b) are more common in women with POP. Urodynamic evidence of voiding difficulty has been found to correlate with POP severity, with high-grade cystocoele being the most common anatomical defect leading to voiding difficulty (Romanzi et al 1999). Severe prolapse of the posterior vaginal compartment has also been shown to have a negative effect on voiding function (Myers et al 1998, Dietz et al 2002). Kinking of the urethra (by a prolapse of the anterior vaginal compartment) or direct pressure on the urethra and bladder neck (by a prolapsing uterus or posterior vaginal compartment) are possible mechanisms of obstruction, leading to voiding difficulty.

Overactive bladder symptoms and occult stress incontinence often coexist with voiding difficulty in women with pelvic organ prolapse (Romanzi et al 1999).

Prolapse correction with a pessary has been shown to improve voiding function in the majority of women with both pathologies (Romanzi et al 1999). In most women with severe prolapse and voiding difficulty, corrective surgery restores voiding successfully (Fitzgerald et al 2000, Liang et al 2008).

Others

In addition to anaesthetics and analgesics, drugs with anticholinergic action (e.g. antidepressants, antipsychotics, oxybutinin etc.) can potentially worsen voiding function and precipitate retention in individual cases. However, antimuscarinic therapy was not found to worsen voiding function in a series of women with overactive bladder and mild voiding difficulty (postvoid residuals of ≥100 ml) (Robinson et al 2003).

Intravescical Botox for treatment of the overactive bladder has been shown to increase postvoid residuals, but retention requiring self-catheterization is uncommon (Duthie et al 2007), with one large series reporting an incidence of 4% (Schmid et al 2006).

Investigations

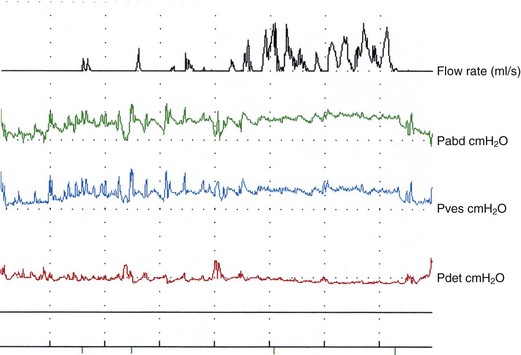

Uroflowmetry

In practical terms, most women with voiding difficulty require simple flow studies with measurement of post void residual urine with catheters or ultrasound. Features include changes in the normal bell-shaped curve, with intermittent or multiple peaked flow (suggestive of abdominal straining or unsustained bladder contractions) (Figure 54.4), and/or low flow rates. Although there are no clear-cut values, low peak flow rates of less than 12–20 ml/s have been used traditionally, with voided volumes of 150–200 ml. Postvoid residual urine volumes of more than 50–100 ml were arbitrarily considered abnormal.

Figure 54.4 Voiding difficulty with obstruction after colposuspension. Note prolonged interrupted flow.

An alternative screening method, using a peak flow rate of less than 15 ml/s and/or postvoid residual urine volume greater than 50 ml with a minimum total bladder volume of 150 ml before voiding, has been shown to correlate well with the Liverpool nomograms (Haylen et al 1989), and could be used if nomogram charts are not available (Costantini et al 2003).

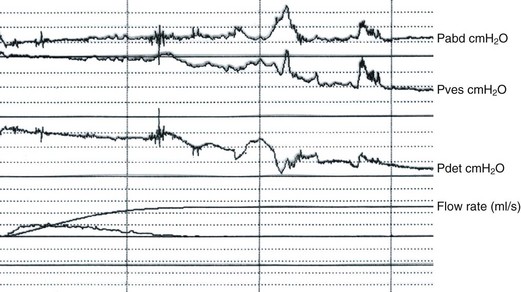

Pressure–flow studies

In an attempt to obtain cut-off values for the definition of obstruction in women, urodynamic studies have been performed in obstructed patients and compared with controls. For example, in repeated non-invasive flow studies, the presence of a peak flow rate of less than 12 ml/s, with a detrusor pressure at maximum flow of more than 20 cmH2O (Figure 54.5), has been considered to be suggestive of obstruction and used to construct female nomograms (Blaivas and Groutz 2000). The practical value of these observations remains unclear, as the clinical and radiological criteria used to define obstruction are arbitrary. Symptoms are often non-specific, and anatomical evidence of obstruction is often missing using videourodynamics or cystourethroscopy (Groutz et al 2000).

In contrast, other authors do not rely heavily on strict urodynamic criteria for the diagnosis of obstruction, and suggest that relative obstruction can exist in the presence of normal or low detrusor pressures (Foster and McGuire 1993, Carr and Webster 1997). Obstruction after incontinence surgery is therefore diagnosed purely on the basis of a clear-cut temporal relationship between surgery and the onset of persistent voiding difficulty. Successful urethrolysis has even been performed on women who had acontractile bladders after stress incontinence surgery (Figure 54.6; Foster and McGuire 1993, Carr and Webster 1997), thus challenging the concept that obstruction only exists in the presence of high pressures.

Videourodynamics

More detailed studies on patients with prolonged postoperative voiding difficulty can be performed using videourodynamics. However, anatomical abnormalities (e.g. a narrowed or deviated urethra) leading to obstruction are only detected in a minority of patients (Groutz et al 2000).

Cystourethroscopy

This has been reported to reveal urethral strictures or fibrosis in approximately half of women who had suspected obstruction during pressure–flow studies (Groutz et al 2000).

Electromyography

Surface or needle electrodes can be used to evaluate distal urethral sphincter function. Failure of the sphincter to relax can be documented in cases of Fowler’s syndrome (Fowler et al 1988). When used with urodynamics, simultaneous detrusor contraction and failure of relaxation of the sphincter can be observed in neuropathic patients (detrusor sphincter dyssynergia).

Management

Short-term management

Voiding difficulty is usually managed with indwelling urethral catheters (e.g. Foley catheters). These are generally well tolerated but have been reported to be unpleasant by more than one-third of patients (Vierhout 1998). Catheters come in a variety of sizes and are made with a variety of materials (e.g. latex, silicone, polyvinyl chloride). Specialized catheters, impregnated with silver or antibiotics, have been developed to reduce the risk of infection, with evidence that they reduce the risk of bacteriuria by one-third to one-half in the short term (Schumm and Lam 2008). There is weak evidence that antibiotic prophylaxis reduces the rate of symptomatic UTI in patients using a urethral catheter in the short term (Niel-Weise and van den Broek 2005).

Long-term management

Indwelling urethral catheters are often used for chronic voiding difficulty, particularly in long-term care settings. While a variety of different catheters exist, insufficient evidence exists to recommend one over another (Jahn et al 2007).

The frequency of catheterization depends on severity of the voiding difficulty and residual urine volume. Old age and disability are not necessarily an impediment, but motivation and manual dexterity are essential. Most patients performing CISC have bacteriuria not requiring antibiotics, and treatment is only required in those with symptoms. More frequent catheterization and an increased fluid intake may be helpful if symptomatic infections occur. At present, there is no evidence that the incidence of UTI in patients performing CISC is affected by variables such as the type of catheter (coated or uncoated) or the technique used (single/sterile or multiple use/clean) (Moore et al 2007).

CISC has been shown to be effective in the long term. Two-thirds of patients available for follow-up 10 years after commencing treatment were satisfied and still performing the procedure, with no evidence of renal impairment (Diokno et al 1983). Although long-term follow-up studies may suffer from selection bias — most available responders are treatment ‘successes’ — up to 80% of patients find CISC easy, with only a minority reporting severe pain (Kessler et al 2009).

Role of surgery

Urethral dilatation and urethrotomy may be effective in patients with voiding difficulty due to urethral narrowing, particularly after anti-incontinence procedures. However, the benefit seems to be short lived as scarring is likely to recur and may even result in worsening obstruction. In addition, stress incontinence has been reported to reappear (Delaere et al 1983). When this method is deemed necessary (e.g. for a traumatic stricture), repeated catheterization (e.g. CISC) is advisable to maintain patency.

Suprapubic and vaginal ‘take-down’ procedures involving urethrolysis, with or without additional resuspension procedures, have been described after retropubic procedures (e.g. colposuspension) (Foster and McGuire 1993, Carr and Webster 1997). Symptoms of voiding difficulty in these patients are usually combined with urgency symptoms. Despite the lack of uniformity with regards to patient selection, definition of obstruction, surgical treatment and outcome measures, it would appear that urethrolysis is a possible alternative to CISC. It may be suitable for patients who are unwilling or unable to perform the technique. However, the reported success rate is variable and unpredictable, and there is a risk of recurrent stress incontinence.

When voiding difficulty occurs after midurethral sling procedures, release of the tape can be performed. Loosening the tape by applying downward traction is usually possible in the immediate postoperative period (2–3 weeks), producing immediate symptomatic relief in most cases. Later, if scarring does not allow tape descent, transection of the tape (laterally or in the midline) has been described (Rardin et al 2002, Laurikainen and Kiiholma 2006, Segal et al 2006). While voiding function has been reported to improve in most women after late tape revisions, coexistent overactive bladder symptoms often remain unchanged (Segal et al 2006, McCrery 2007). The reported risk of recurrent stress incontinence after tape revision ranges from 5% to 50% (Klutke et al 2001, Rardin et al 2002, Karram et al 2003). Urethral injury may occur due to the formation of dense scarring between tape and urethra (Klutke et al 2001, Laurikainen and Kiiholma 2006).

Role of nerve stimulation

Posterior tibial nerve stimulation involves the placement of needle electrodes above the medial malleolus to stimulate the posterior tibial nerve, which contains mixed fibres from L5–S3. Early reports show objective improvement in voiding function, with approximately 60% of patients willing to continue treatment (Vandoninck et al 2004). However, the technique is time consuming and requires repeat stimulation.

Sacral nerve stimulation is a promising technique that uses an implantable system (Interstim device) to stimulate the pelvic nerves (at S3 level). An initial test procedure is performed to assess response, positioning a temporary electrode with an external stimulator. If appropriate, a permanent lead is then inserted and connected to a pulse generator positioned in the upper buttocks or anterior abdominal wall. In addition to unobstructed voiding difficulty, indications for sacral nerve stimulation include faecal incontinence, bladder overactivity and interstitial cystitis. A recent review reports a response rate for voiding difficulty of 38–68%, with good medium-term results in 58–76% of responders (Bosch 2006). Technical problems and adverse events are unfortunately common (e.g. pain at the stimulator site, new pain, pain at the lead site, lead migration, infection, transient electric shock, changes in bowel function), with a reoperation rate of approximately 50% (Bosch 2006). There are no reports of long-lasting neurological complications.

Other treatments

A suprapubic vibration device (Queen Square bladder stimulator) has been shown to improve voiding in some patients with neurogenic bladders (Dasgupta et al 1997). The device was only effective in patients with a postvoid residual of less than 400 ml, reducing the postvoid residual from a mean of 175 ml to a mean of 68 ml (Dasgupta et al 1997). However, there is no evidence of benefit in other types of voiding difficulty.

Prevention

Although urodynamics are not considered essential prior to stress incontinence surgery in all women (National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence 2006), pressure–flow studies may help to identify women with existing or borderline voiding difficulty. Preoperative urodynamic variables (e.g. straining during voiding, voiding with low or absent detrusor contraction, low peak flow rate) may be predictive of postoperative voiding difficulty (Figures 54.2, 54.3 and 54.7), although the reported evidence is inconsistent. If urodynamics are not performed routinely, screening of women prior to surgery in order to identify those with voiding difficulty is simple and non-invasive (e.g. using uroflowmetry and/or ultrasound to check postvoid residual urine volumes). Elderly women and patients undergoing multiple procedures at the same time (e.g. midurethral slings combined with POP surgery) may be at increased risk of postoperative voiding difficulty. Patients at risk should be managed by experienced clinicians. Careful counselling is important in all cases. In women with existing voiding difficulty, consideration should be given to teaching CISC.

During surgery for urinary incontinence, excessive elevation should be avoided during colposuspension. For women undergoing midurethral sling procedures, it has been suggested that the cough test, with the observation of a reduction in leakage after tensioning the tape, can reduce the risk of postoperative voiding difficulty (Ulmsten et al 1996). However, the evidence for this is inconclusive, and in practice, the cough test is often poorly reproducible and influenced by the type of anaesthetic used. Consideration should be given to use of the TOT procedure in women at risk, as this is shown to be less likely to cause voiding difficulty (Latthe et al 2007).

A potentially difficult group of patients are those with intrinsic sphincter deficiency, as shown by reduced urethral closure pressures using urethral pressure profilometry. The TOT procedure has been shown to have a lower success rate than the TVT procedure in these patients (Schierlitz et al 2008). This is because the TOT procedure is less obstructive, and successful treatment of stress incontinence in such patients often entails urethral support with an additional element of obstruction and the placement of a tighter tape; minimal degrees of tension can be crucial to achieve success without causing voiding difficulty. These women should be managed by experienced surgeons. A cough test in these circumstances may be useful as a measure of tension. The use of adjustable tapes has been proposed in patients with intrinsic sphincter deficiency, as well as in those at risk of voiding difficulty, as the tension can be modified in the postoperative period (Araco et al 2008, Romero Maroto et al 2008).

Box 54.2 shows the key points for prevention.

Box 54.2 Prevention

key points

KEY POINTS

Araco F, Gravante G, Dati S, Bulzomi V, Sesti F, Piccione E. Results 1 year after the Reemex system was applied for the treatment of stress urinary incontinence cause by intrinsic sphincter deficiency. International Urogynecology Journal and Pelvic Floor Dysfunction. 2008;19:783-786.

Athanasopoulos A, Gyftopoulos K, Giannitsas K, Perimenis P. Effect of alfuzosin on female primary bladder neck obstruction. International Urogynecology Journal and Pelvic Floor Dysfunction. 2009;20:217-222.

Bartolin Z, Gilja I, Bedalov G, Savic I. Bladder function in patients with lumbar intervertebral disk protrusion. Journal of Urology. 1998;159:969-971.

Bartolin Z, Vilendecic M, Derezic D. Bladder function after surgery for lumbar intervertebral disk protrusion. Journal of Urology. 1999;161:1885-1887.

Blaivas JG, Groutz A. Bladder outlet obstruction nomogram for women with lower urinary tract symptomatology. Neurourology and Urodynamics. 2000;19:553-564.

Bosch JL. Electrical neuromodulatory therapy in female voiding dysfunction. BJU International. 2006;98(Suppl 1):43-48.

Carey MP, Goh JT, Rosamilia A, et al. Laparoscopic versus open Burch colposuspension: a randomised controlled study. BJOG: an International Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 2006;113:999-1006.

Carr LK, Webster GD. Voiding dysfunction following incontinence surgery: diagnosis and treatment with retropubic or vaginal urethrolysis. Journal of Urology. 1997;157:821-823.

Choudhari K, Choudhari Y, Fannin T. Acute lumbar intervertebral disc prolapse: a complication of the lithotomy position. BJOG: an International Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 2000;107:1519-1521.

Coates KW, Harris RL, Cundiff GW, Bump RC. Uroflowmetry in women with urinary incontinence and pelvic organ prolapse. British Journal of Urology. 1997;80:217-221.

Costantini E, Mearini E, Pajoncini C, Biscotto S, Bini V, Porena M. Uroflowmetry in female voiding disturbances. Neurourology and Urodynamics. 2003;22:569-573.

Dasgupta P, Haslam C, Goodwin R, Fowler CJ. The ‘Queen Square bladder stimulator’: a device for assisting emptying of the neurogenic bladder. British Journal of Urology. 1997;80:234-237.

Delaere KPJ, Debruyne FMJ, Moonen WA. Bladder neck incision in the female: a hazardous procedure? British Journal of Urology. 1983;55:283-286.

Dietz HP, Haylen BT, Vancaillie TG. Female pelvic organ prolapse and voiding dysfunction. International Urogynecology Journal and Pelvic Floor Dysfunction. 2002;13:284-288.

Digesu GA, Chaliha C, Salvatore S, Hutchings A, Khullar V. The relationship of vaginal prolapse severity to symptoms and quality of life. BJOG: an International Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 2005;112:971-976.

Diokno AC, Sonda P, Hollander JB, Lapides J. Fate of patients started on clean intermittent catheterisation therapy 10 years ago. Journal of Urology. 1983;129:1120-1121.

Duthie J, Wilson DI, Herbison GP, Wilson D 2007 Botulinum toxin injections for adults with overactive bladder syndrome. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 3: CD005493.

Fitzgerald MP, Kulkami N, Fenner D. Postoperative resolution of urinary retention in patients with advanced pelvic organ prolapse. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2000;183:1361-1364.

Foster HE, McGuire EJ. Management of urethral obstruction with transvaginal urethrolysis. Journal of Urology. 1993;150:1448-1451.

Fowler CJ, Christmas TJ, Chapple CR, Parkhouse HF, Kirby RS, Jacobs HS. Abnormal electromyographic activity of the urethral sphincter, voiding dysfunction and polycystic ovaries: a new syndrome? BMJ (Clinical Research Ed.). 1988;297:1436-1438.

Glavind K, Bjørk J. Incidence and treatment of urinary retention postpartum. International Urogynecology Journal and Pelvic Floor Dysfunction. 2003;14:119-121.

Groutz A, Blaivas JG, Chaikin DC. Bladder outlet obstruction in women: definition and characteristics. Neurourology and Urodynamics. 2000;19:213-220.

Hakvoort RA, Elberink R, Vollebregt A, Ploeg T, Emanuel MH. How long should urinary bladder catheterisation be continued after vaginal prolapse surgery? A randomised controlled trial comparing short term versus long term catheterisation after vaginal prolapse surgery. BJOG: an International Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 2004;111:828-830.

Hakvoort RA, Dijkgraaf MG, Burger MP, Emanuel MH, Roovers JP. Predicting short-term urinary retention after vaginal prolapse surgery. Neurourology and Urodynamics. 2009;28:225-228.

Haylen BT, Ashby D, Sutherst JR, Frazer MI, West CR. Maximum and average urine flow rates in normal male and female populations — the Liverpool nomograms. British Journal of Urology. 1989;64:30-38.

Haylen BT, Krishnan S, Schulz S, et al. Has the true prevalence of voiding dysfunction in urogynecology patients been underestimated? International Urogynecology Journal and Pelvic Floor Dysfunction. 2007;18:53-56.

Haylen BT, Yang V, Logan V. Uroflowmetry: its current clinical utility for women. International Urogynecology Journal and Pelvic Floor Dysfunction. 2008;19:899-903.

Haylen BT, Lee J, Logan V, Husselbee S, Zhou J, Law M. Immediate postvoid residual volumes in women with symptoms of pelvic floor dysfunction. Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2008;111:1305-1312.

Haylen BT, de Ridder D, Freeman RM, et al. An International Urogynecological Association (IUGA)/International Continence Society (ICS) Joiunt Report on the Terminology of Remale Pelvic Floor Dysfunction. International Urogynecology Journal and Pelvic Floor Dysfunction. 2010;21:5-26.

Jahn P, Preuss M, Kernig A, Seifert-Huhmer A, Langer G 2007 Types of indwelling catheters for long-term bladder drainage in adults. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 3: CD004997.

Jarvik JG, Deyo RA. Diagnostic evaluation of low back pain with emphasis on imaging. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2007;147:478-491.

Jarvis JG. Surgery for genuine stress incontinence. BJOG: an International Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 1994;101:371-374.

Karram MM, Partoll L, Bilotta V, Angel O. Factors affecting detrusor contraction strength during voiding in women. Obstetrics and Gynecology. 1997;90:723-726.

Karram MM, Segal JL, Vassallo BJ, Kleeman SD. Complications and untoward effects of the tension-free vaginal tape procedure. Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2003;101:929-932.

Kessler TM, Ryu G, Burkhard FC. Clean intermittent self-catheterization: a burden for the patient? Neurourology and Urodynamics. 2009;28:18-21.

Khullar V, Cardozo LD, Abbott D, Anders K. GAX collagen in the treatment of urinary incontinence in elderly women: a two year follow-up. BJOG: an International Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 1997;104:96-99.

Klutke C, Siegel S, Carlin B, Paszkiewicz E, Kirkemo A, Klutke J. Urinary retention after tension-free vaginal tape procedure: incidence and treatment. Urology. 2001;58:697-701.

Kuuva N, Nilsson CG. A nationwide analysis of complications associated with the tension-free vaginal (TVT) procedure. Acta Obstetricia et Gynecologica Scandinavica. 2002;81:72-77.

Lapides J, Diokno AC, Gould FR, Lowe BS. Further observations on self catheterisation. Journal of Urology. 1976;116:169-171.

Latthe PM, Foon R, Tooz-Hobson P. Transobturator tape procedures in stress urinary incontinence: a systematic review and meta-analysis of effectiveness and complications. BJOG: an International Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 2007;114:522-531.

Laurikainen E, Kiiholma P. A nationwide analysis of transvaginal tape release for urinary retention after tension-free vaginal tape procedure. International Urogynecology Journal and Pelvic Floor Dysfunction. 2006;17:111-119.

Liang CC, Tseng LH, Chang SD, Chang YL, Lo TS. Resolution of elevated postvoid residual volumes after correction of severe pelvic organ prolapse. International Urogynecology Journal and Pelvic Floor Dysfunction. 2008;19:1261-1266.

Malone-Lee J, Wahedna I. Characterisation of detrusor contractile function in relation to old age. British Journal of Urology. 1993;72:873-880.

Massey JA, Abrams PH. Obstructed voiding in the female. British Journal of Urology. 1988;61:36-39.

McCrery R. Transvaginal urethrolysis for obstruction after anti-incontinence surgery. International Urogynecology Journal and Pelvic Floor Dysfunction. 2007;18:627-633.

Moore KN, Fader M, Getliffe K 2007 Long-term bladder management by intermittent catheterisation in adults and children. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 4: CD006008.

Myers DL, Lasala CA, Hogan JW, Rosenblatt PL. 1998 The effect of posterior wall support defects on urodynamic indices in stress urinary incontinence. Obstetrics and Gynecology. 1998;91:710-714.

National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. Urinary Incontinence. NICE Clinical Guideline No. 40. NICE, London. Available at www.nice.org.uk, 2006.

Niel-Weise BS, van den Broek PJ 2005 Antibiotic policies for short-term catheter bladder drainage in adults. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 3: CD005428.

Ramsay IN, Torbet TE. Incidence of abnormal voiding parameters in the immediate postpartum period. Neurourology and Urodynamics. 1993;12:179-183.

Rardin CR, Rosenblatt PL, Kohli N, Miklos JR, Heit M, Lucente VR. Release of tension-free vaginal tape for the treatment of refractory postoperative voiding dysfunction. Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2002;100:898-902.

Robinson D, Dixon A, Cardozo L, Anders K, Balmforth J, Parsons M. Does antimuscarinic therapy exacerbate voiding difficulties? Neurourology and Urodynamics. 2003;22:535-536.

Romanzi LJ, Chaikin DC, Blaivas JG. The effect of genital prolapse on voiding. Journal of Urology. 1999;161:581-586.

Romero Maroto J, Ortiz Gorraiz M, Prieto Chaparro L, Pacheco Bru J, Miralles Bueno J, Lopez Lopez C. Transvaginal adjustable tape: an adjustable mesh for surgical treatment of female stress urinary incontinence. International Urogynecology Journal and Pelvic Floor Dysfunction. 2008;19:1109-1116.

Schaeffer AJ. Catheter-associated bacteriuria. Urologic Clinics of North America. 1986;13:735-747.

Schierlitz L, Dwyer PL, Rosamilia A, et al. Effectiveness of tension-free vaginal tape compared with transobturator tape in women with stress urinary incontinence and intrinsic sphincter deficiency: a randomised controlled trial. Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2008;112:1253-1261.

Schmid DM, Sauerman P, Werner M, et al. Experience with 100 cases treated with botulinum-A toxin injections in the detrusor muscle for idiopathic overactive bladder syndrome refractory to anticholinergics. Journal of Urology. 2006;176:177-185.

Schumm K, Lam TBL. Types of urethral catheters for management of short-term voiding problems in hospitalised adults: a short version Cochrane review. Neurourology and Urodynamics. 2008;27:738-746.

Scotti RJ, Bergman A, Bhatia NN, Ostergard DR. Urodynamic changes in urethrovesical function after radical hysterectomy. Obstetrics and Gynecology. 1986;68:111-120.

Segal J, Steele AC, Vassallo BJ, et al. Various surgical approaches to treat voiding dysfunction following anti-incontinence surgery. International Urogynecology Journal and Pelvic Floor Dysfunction. 2006;17:372-377.

Smith P. Age changes in the female urethra. British Journal of Urology. 1972;44:667-676.

Stanton SL, Norton C, Cardozo L. Clinical and urodynamic effects of anterior colporrhaphy and vaginal hysterectomy for prolapse with and without incontinence. BJOG: an International Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 1982;89:459-463.

Thakar R, Ayers S, Clarkson P, Stanton S, Manyonda I. Outcomes after total versus subtotal abdominal hysterectomy. New England Journal of Medicine. 2002;347:1318-1325.

Ulmsten U, Henriksson L, Johnson P, Varhos G. An ambulatory surgical procedure under local anesthesia for treatment of female urinary incontinence. International Urogynecology Journal and Pelvic Floor Dysfunction. 1996;7:81-86.

Vandoninck V, van Balken MR, Finazzi Agrò E, et al. Posterior tibial nerve stimulation in the treatment of voiding dysfunction: urodynamic data. Neurourology and Urodynamics. 2004;23:246-251.

Vervest HA, Bisseling TM, Heintz AP, Schraffordt Koops SE. The prevalence of voiding difficulty after TVT, its impact on quality of life and related risk factors. International Urogynecology Journal and Pelvic Floor Dysfunction. 2007;18:173-182.

Vierhout ME. Prolonged catheterisation after vaginal prolapse surgery. Acta Obstetricia et Gynecologica Scandinavica. 1998;77:997-999.

Wake CR. The immediate effect of abdominal hysterectomy on intravesical pressure and detrusor activity. BJOG: an International Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 1980;87:901-902.

Ward K, Hilton P. Prospective multicentre randomised trial of tension-free vaginal tape and colposuspension as primary treatment for stress incontinence. BMJ (Clinical Research Ed.). 2002;325:67-70.

Yu HJ, Lee WC, Liu SP, Tai TY, Wu HP, Chen J. Unrecognized voiding difficulty in female type 2 diabetic patients in the diabetes clinic: a prospective case–control study. Diabetes Care. 2004;27:988-989.