9

Vitreous

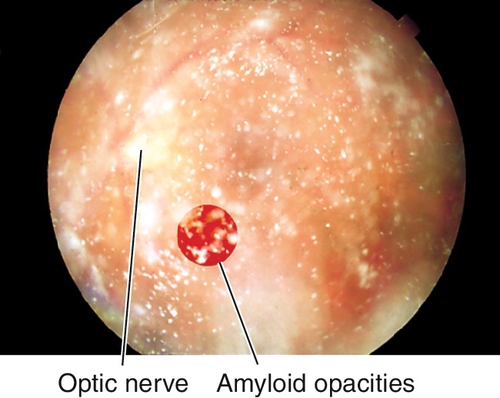

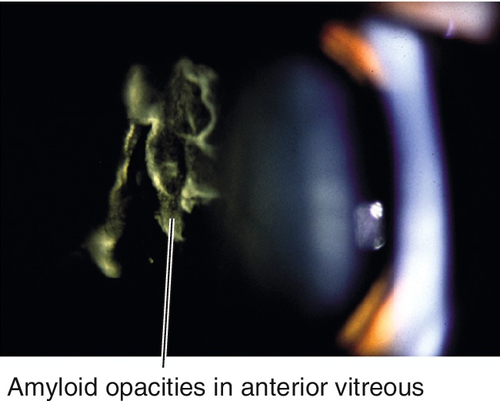

Amyloidosis

Definition

Group of diseases characterized by abnormal protein production and tissue deposition. Nonfamilial and familial forms; familial amyloidosis (autosomal dominant [AD]) caused by substitution errors in coding of prealbumin. Can be associated with multiple myeloma.

Symptoms

Floaters, decreased vision; may have diplopia.

Signs

Although any part of the eye can be involved, vitreous involvement is most commonly seen with granular, glass-wool opacities that form in the vitreal cortex, strands attached to the retina, retinal vascular occlusions, cotton wool spots, retinal neovascularization, and compressive optic neuropathy. Other findings include eyelid hemorrhages, ptosis, proptosis, dry eye, corneal deposits, iris stromal infiltrates, and ophthalmoplegia. Systemic findings in nonfamilial forms include polyarthralgias, pulmonary infiltrates, waxy, maculopapular skin lesions, renal failure, postural hypotension, congestive heart failure, and gastrointestinal bleeds. Systemic findings in familial form include autonomic dysfunction, peripheral neuropathies, and cardiomyopathy.

Differential Diagnosis

Asteroid hyalosis (see below), vitritis, old vitreous hemorrhage.

Evaluation

• Lab tests: Complete blood count (CBC), serum protein electrophoresis, liver function tests, chest radiographs, and 12-lead electrocardiogram.

• Diagnosis made on biopsy (dichroism; birefringence with Congo red stain).

• Medical consultation.

Prognosis

Variable depending on systemic involvement.

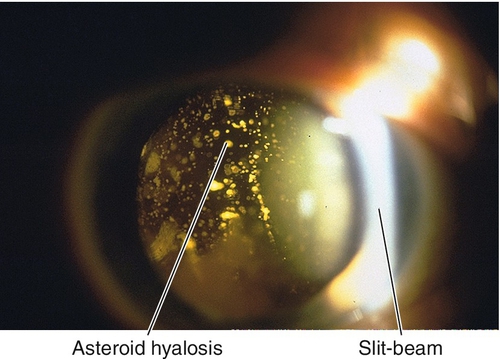

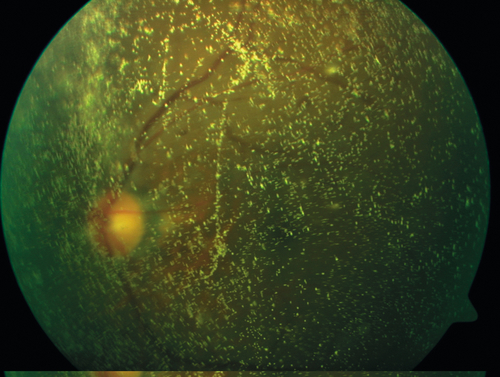

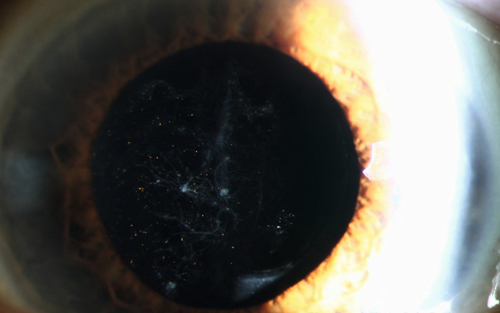

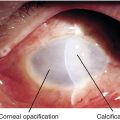

Asteroid Hyalosis

Multiple, yellow-white, round, birefringent particles composed of calcium phosphate soaps attached to the vitreous framework. Common degenerative process in elderly patients over 60 years of age (0.5% of population). Usually asymptomatic, does not cause floaters or interfere with vision, but does affect view of fundus; usually unilateral (75%); associated with diabetes mellitus (30%); good prognosis. Also does not affect fluorescein angiogram (FA) or optical coherence tomography (OCT) so both tests can be used to determine whether there are any retinal problems when the asteroid particles impair a direct view of the retina.

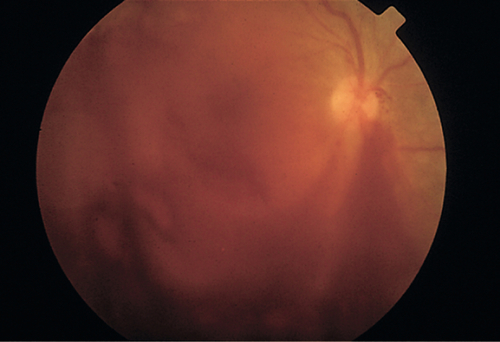

Persistent Hyperplastic Primary Vitreous (Persistent Fetal Vasculature Syndrome)

Definition

Sporadic, unilateral (90%), developmental anomaly with abnormal regression of the tunica vasculosa lentis (hyaloid artery) and primary vitreous. Possibly due to abnormality of PAX6 gene.

Symptoms

Decreased vision; may have eye turn.

Signs

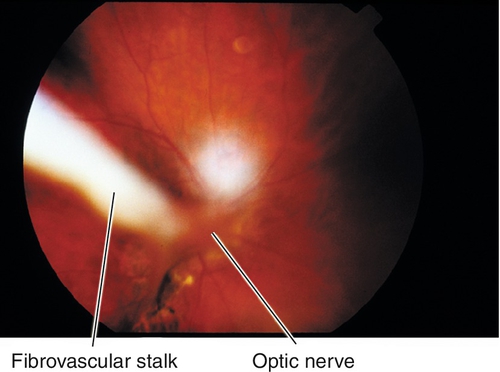

Leukocoria, papillary strands, strabismus, microphthalmos, nystagmus, pink-white retrolenticular/intravitreal membrane often with radiating vessels, “inverted Y” fibrovascular stalk emanating from optic nerve, Mittendorf dot; lens is clear early but becomes cataractous; associated with shallow anterior chamber (AC) (more shallow with age), elongated ciliary processes extending toward membrane, large radial blood vessels that often cover iris; may have angle-closure glaucoma (see Chapter 6), vitreous hemorrhage, or retinal detachment.

Differential Diagnosis

Leukocoria (see Chapter 7).

Evaluation

• B-scan ultrasonography if unable to visualize the fundus.

• Check orbital computed tomography (CT) scan or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) for intraocular calcifications.

• Visual evoked potential (VEP) useful to decide whether to operate or not.

Prognosis

Visual outcomes depend on degree of maldevelopment; poor without treatment especially with posterior involvement secondary to glaucoma, recurrent vitreous hemorrhages, and eventually phthisis; earlier treatment improves prognosis.

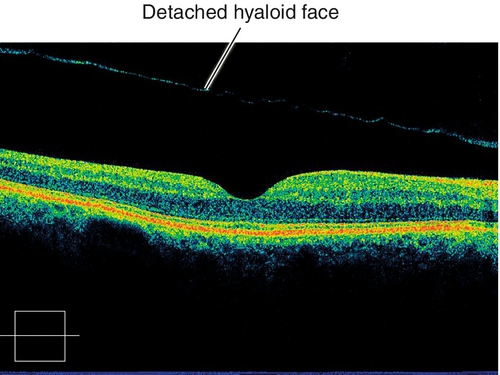

Posterior Vitreous Detachment

Definition

Syneresis (liquefaction) of the vitreous gel that causes dehiscence of the posterior hyaloid from the retina and collapse of the vitreous toward the vitreous base away from the macula and optic disc. Can be localized, partial, or total.

Epidemiology

Most commonly caused by aging (53% by 50 years old, 65% by 65 years old); by age 70, majority of the posterior vitreous is liquefied (synchysis senilis); female predilection. Occurs earlier after trauma, vitritis, cataract surgery, neodymium : yttrium–aluminum–garnet (Nd : YAG) laser posterior capsulotomy, and in patients with myopia, diabetes mellitus, hereditary vitreoretinal degenerations, and retinitis pigmentosa.

Symptoms

Acute onset of floaters and photopsias, especially with eye movement.

Signs

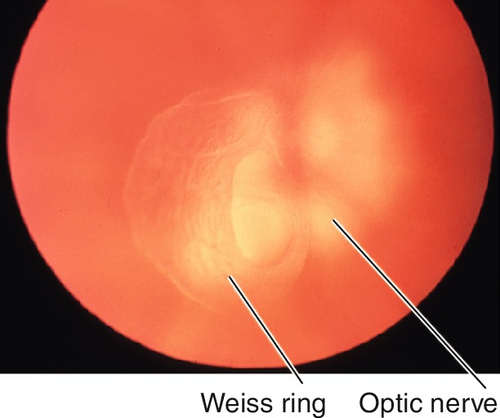

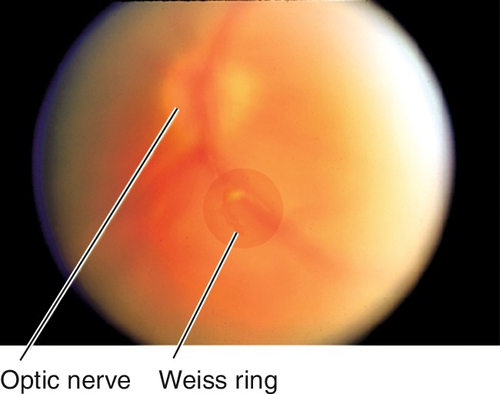

Circular vitreous condensation often over disc (Weiss ring), anterior displacement of the posterior hyaloid, vitreous opacities; may have vitreous pigment cells (tobacco dust), focal intraretinal, preretinal, or vitreous hemorrhage.

Differential Diagnosis

Vitreous hemorrhage (see below), vitritis, fungal cyst.

Evaluation

Prognosis

Good; 10–15% risk of retinal break in acute, symptomatic posterior vitreous detachments; 70% risk of retinal break if vitreous hemorrhage is present.

Synchesis Scintillans

Golden brown, refractile cholesterol crystals that are freely mobile within vitreous cavity; associated with liquid vitreous, so the crystals settle inferiorly which is the most dependent area of the vitreous body. Rare, unilateral syndrome that occurs after chronic vitreous hemorrhage, uveitis, or trauma.

Vitreous Hemorrhage

Definition

Blood in the vitreous space.

Etiology

Retinal break, posterior vitreous detachment, ruptured retinal arterial macroaneurysm, juvenile retinoschisis, familial exudative vitreoretinopathy, Terson’s syndrome (blood dissects through the lamina cribrosa into the eye due to subarachnoid hemorrhage and elevated intracranial pressure, often bilateral with severe headache), trauma, retinal angioma, retinopathy of blood disorders, Valsalva retinopathy, and neovascularization from various disorders including diabetic retinopathy, Eales’ disease, hypertensive retinopathy, radiation retinopathy, sickle cell retinopathy, and retinopathy of prematurity.

Symptoms

Sudden onset of floaters and decreased vision.

Signs

Decreased visual acuity, vitreous cells (red blood cells), poor or no view of fundus, poor or absent red reflex; old vitreous hemorrhage appears gray-white.

Differential Diagnosis

Vitritis, asteroid hyalosis, pigment cells, pars planitis.

Evaluation

• B-scan ultrasonography to rule out retinal tear or detachment if unable to visualize the fundus.

Prognosis

Usually good.

Vitritis

Inflammation of the vitreous characterized by vitreous white blood cells. Vitritis is a form of uveitis and is associated with anterior uveitis and more commonly intermediate or posterior uveitis; the degree of vitritis is graded on a 1 to 4 scale depending upon how limited the view of the retinal structures is (i.e., 1+ = few cells with mild obscuration of retina; 2+ = nerve and vessels visible; 3+ = only nerve and large vessels visible; 4+ = nerve and vessels not visible). It is important to distinguish vitritis from other types of cells in the vitreous cavity such as red blood cells (vitreous hemorrhage), pigment cells (retinal tear), and tumor cells (lymphoma, retinoblastoma, choroidal melanoma). The underlying etiology of the inflammation must be determined so that appropriate treatment can be given (see Uveitis sections in Chapters 6 and 10).