Chapter 46 Vitamin B Complex Deficiency and Excess

46.1 Thiamine (Vitamin B1)

Boonsiri P, Tangrassameeprasert R, Panthongviriyakul C, Yongvanit P. A preliminary study of thiamine status in northeastern Thai children with acute diarrhea. Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health. 2007;38:1120-1125.

Fattal-Valevski A, Kesler A, Sela BA, et al. Outbreak of life-threatening thiamine deficiency in infants in Israel caused by a defective soy-based formula. Pediatrics. 2005;115:e233-e238.

Kornreich L, Bron-Harlev E, Hoffmann C, et al. Thiamine deficiency in infants: MR findings in the brain. Am J Neuroradiol. 2005;26:1668-1674.

Ricketts CJ, Minton JA, Samuel J, et al. Thiamine-responsive megaloblastic anaemia syndrome: long-term follow-up and mutation analysis of seven families. Acta Paediatr. 2006;95:99-104.

46.2 Riboflavin (Vitamin B2)

Deficiency

Clinical Manifestations

Clinical features of riboflavin deficiency include cheilosis, glossitis, keratitis, conjunctivitis, photophobia, lacrimation, corneal vascularization, and seborrheic dermatitis. Cheilosis begins with pallor at the angles of the mouth and progresses to thinning and maceration of the epithelium, leading to fissures extending radially into the skin (Fig. 46-1). In glossitis, the tongue becomes smooth, with loss of papillary structure (Fig. 46-2). Normochromic, normocytic anemia may also be seen because of the impaired erythropoiesis. A low riboflavin content of the maternal diet has been linked to congenital heart defects, but the evidence is weak.

Prevention

The recommended daily allowance (RDA) of riboflavin for infants, children and adolescents is presented in Table 46-1. Adequate consumption of milk, milk products, and eggs prevents riboflavin deficiency. Fortification of cereal products is helpful for those who follow vegan diets or are consuming inadequate amounts of milk products because of other reasons.

Bugiani M, Lamantea E, Invernizzi F, et al. Effects of riboflavin in children with complex II deficiency. Brain Dev. 2006;28:576-581.

Rohner F, Zimmermann MB, Wegmueller R, et al. Mild riboflavin deficiency is highly prevalent in school-age children but does not increase risk for anaemia in Côte d’Ivoire. Br J Nutr. 2007;97:970-976.

Shaw NS, Wang JL, Pan WH, et al. Thiamin and riboflavin status of Taiwanese elementary schoolchildren. Asia Pac J Clin Nutr. 2007;16(Suppl 2):564-571.

Smedts HP, Rakhshandehroo M, Verkleij-Hagoort AC, et al. Maternal intake of fat, riboflavin and nicotinamide and the risk of having offspring with congenital heart defects. Eur J Nutr. 2008;47:357-365.

46.3 Niacin (Vitamin B3)

Deficiency

Clinical Manifestations

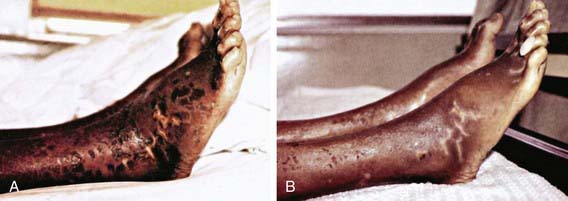

The early symptoms of pellagra are vague: anorexia, lassitude, weakness, burning sensations, numbness, and dizziness. After a long period of deficiency, the classic triad of dermatitis, diarrhea, and dementia appears. Dermatitis, the most characteristic manifestation of pellagra, can develop suddenly or insidiously and may be initiated by irritants, including intense sunlight. The lesions first appear as symmetric areas of erythema on exposed surfaces, resembling sunburn, and might go unrecognized. The lesions are usually sharply demarcated from the surrounding healthy skin, and their distribution can change frequently. The lesions on the hands and feet often have the appearance of a glove or stocking (Fig. 46-3). Similar demarcations can also occur around the neck (Casal necklace) (see Fig. 46-3). In some cases, vesicles and bullae develop (wet type). In others, there may be suppuration beneath the scaly, crusted epidermis, and in still others, the swelling can disappear after a short time, followed by desquamation (Fig. 46-4). The healed parts of the skin might remain pigmented. The cutaneous lesions may be preceded by or accompanied by stomatitis, glossitis, vomiting, and/or diarrhea. Swelling and redness of the tip of the tongue and its lateral margins is often followed by intense redness, even ulceration, of the entire tongue and the papillae. Nervous symptoms include depression, disorientation, insomnia, and delirium.

Figure 46-3 Characteristic skin lesions of pellagra on hands and lesions on the neck (Casal necklace).

(Courtesy of Dr. J.D. MacLean, McGill Centre for Tropical Diseases, Montreal, Canada.)

Birjmohun RS, Hutten BA, Kastelein JJ, Stroes ES. Efficacy and safety of high-density lipoprotein cholesterol–increasing compounds: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2005;45:185-197.

Creeke PI, Dibari F, Cheung E, et al. Whole blood NAD and NADP concentrations are not depressed in subjects with clinical pellagra. J Nutr. 2007;137:2013-2017.

Jagielska G, Tomaszewicz-Libudzic EC, Brzozowska A. Pellagra: a rare complication of anorexia nervosa. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2007;16:417-420.

Seal AJ, Creeke PI, Dibari F, et al. Low and deficient niacin status and pellagra are endemic in postwar Angola. Am J Clin Nutr. 2007;85:218-224.

46.4 Vitamin B6 (Pyridoxine)

Deficiency

Clinical Manifestations

Several types of vitamin B6 dependence syndromes, presumably due to errors in enzyme structure or function, respond to very large amounts of pyridoxine (see Table 46-1). These syndromes include pyridoxine-dependent seizures, a vitamin B6–responsive anemia, xanthurenic aciduria, cystathioninuria, and homocystinuria (Chapters 79, 448, and 586).

Been JV, Bok LA, Andriessen P, Renier WO. Epidemiology of pyridoxine dependent seizures in the Netherlands. Arch Dis Child. 2005;90:1293-1296.

Nye C, Brice A: Combined vitamin B6-magnesium treatment in autism spectrum disorder, Cochrane Database Syst Rev (19):CD003497, 2005.

Teune LK, vd Hoeven JH, Maurits NM, et al. Pyridoxine induces non-specific EEG alterations in infants with therapy resistant seizures. Seizure. 2007;16:459-464.

46.5 Biotin

The clinical findings of biotin deficiency include scaly periorificial dermatitis, conjunctivitis, thinning of hair, and alopecia. Central nervous system abnormalities seen with biotin deficiency are lethargy, hypotonia, and withdrawn behavior. Biotin deficiency can be successfully treated using 1-10 mg of biotin orally daily. The adequate dietary intake values for biotin are 5 µg/day for 0-6 mo, 6 µg/day for 7-12 mo, 8 µg/day for ages 1-3 yr, 12 µg/day for ages 4-8 yr, 20 µg/day for ages 9-13 yr, and 25 µg/day for ages 14-18 yr. No toxic effects have been reported with very high doses. Conditions involving deficiencies in the enzymes holocarboxylase synthetase and biotinidase that respond to treatment with biotin are described in Chapter 79.6.

46.6 Folate

Allen LH. Causes of vitamin B12 and folate deficiency. Food Nutr Bull. 2008;29(2 Suppl):S20-S34.

Gordon N. Cerebral folate deficiency. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2009;51:180-182.

Qiu A, Jansen M, Sakaris A, et al. Identification of an intestinal folate transporter and the molecular basis for hereditary folate malabsorption. Cell. 2006;127:917-928.

Taneja S, Bhandari N, Strand TA, et al. Cobalamin and folate status in infants and young children in a low-to-middle income community in India. Am J Clin Nutr. 2007;86:1302-1309.

Wilson RD, Johnson JA, Wyatt P, et al. Pre-conceptional vitamin/folic acid supplementation 2007: the use of folic acid in combination with a multivitamin supplement for the prevention of neural tube defects and other congenital anomalies. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2007;29:1003-1026.

46.7 Vitamin B12 (Cobalamin)

Deficiency

Clinical Manifestations

The hematologic manifestations of vitamin B12 deficiency are similar to manifestations of folate deficiency and are discussed in Chapter 448.2. Irritability, hypotonia, developmental delay, developmental regression, and involuntary movements are the common neurologic symptoms in infants and children, whereas sensory deficits, paresthesias, and peripheral neuritis are seen in adults. Hyperpigmentation of the knuckles and palms is another common observation with B12 deficiency in children.

Andrès E, Dali-Youcef N, Vogel T, et al. Oral cobalamin (vitamin B12) treatment. An update. Int J Lab Hematol. 2009;31:1-8.

Bjørke-Monsen AL, Torsvik I, Saetran H, et al. Common metabolic profile in infants indicating impaired cobalamin status responds to cobalamin supplementation. Pediatrics. 2008;122:83-91.

Coelho D, Suormala T, Stucki M, et al. Gene identification for the cb1D defect of vitamin B12 metabolism. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:1454-1464.

Dror DK, Allen LH. Effect of vitamin B12 deficiency on neurodevelopment in infants: current knowledge and possible mechanisms. Nutr Rev. 2008;66:250-255.

Hudson B. Vitamin B-12 deficiency. BMJ. 2010;340:c2305.

Marble M, Copeland S, Khanfar N, Rosenblatt DS. Neonatal vitamin B12 deficiency secondary to maternal subclinical pernicious anemia: identification by expanded newborn screening. J Pediatr. 2008;152:731-733.

Marsch AF, Shashidhar H, D’Orazio JA. B12 deficient megaloblastic anemia in a toddler with a history of gastroschisis. J Pediatr. 2011;158:512.

McLean E, de Benoist B, Allen LH. Review of the magnitude of folate and vitamin B12 deficiencies worldwide. Food Nutr Bull. 2008;29(2 Suppl):S38-S51.

Molloy AM, Kirke PN, Brody LC, et al. Effects of folate and vitamin B12 deficiencies during pregnancy on fetal, infant, and child development. Food Nutr Bull. 2008;29(2 Suppl):S101-S111.

Vidal-Alaball J, Butler CC, Cannings-John R, et al: Oral vitamin B12 versus intramuscular vitamin B12 for vitamin B12 deficiency, Cochrane Database Syst Rev (3):CD004655, 2005.