Vital Signs

After reading this chapter, you will be able to:

1. Identify the four classic vital signs and the value of monitoring their trends.

2. Recognize the clinical significance of other bedside clinical findings including abnormal sensorium and level of pain.

3. Describe the normal values of the following vital signs and common causes of deviation from normal in the adult:

4. Describe the following issues related to body temperature measurement:

a. Types of devices commonly used

b. Factors affecting the accuracy of devices

c. Common sites and temperature ranges of those sites for measurement

5. Describe how fever affects the following:

a. Oxygen consumption and carbon dioxide production

6. Define the following terms:

7. Describe the technique, common sites for palpation, and characteristics for evaluating the pulse.

8. Describe the techniques for determining respiratory rate and blood pressure.

9. Explain how hypotension affects perfusion and tissue oxygen delivery.

10. Identify the factors that cause erroneously elevated blood pressure measurements.

11. Describe the mechanism by which pulsus paradoxus is produced.

The previous two chapters focused on subjective data—those that are perceived by the patient. We now turn our attention to more objective data—those that can be measured. Although subjective data are important, objective data are factual information that is generally not influenced by patient opinion or feelings. Therefore, they are most often relied on to make important clinical decisions. This chapter focuses mainly on vital signs, the most frequently measured objective data for monitoring vital body functions and often the first and most important indicator that the patient’s condition is changing. Given that obtaining vital signs generally requires direct patient interaction, the respiratory therapist (RT) or other member of the patient care team should give proper consideration to the principles relating to preparing for the patient encounter, as outlined in Chapter 1.

Vital signs are used for the following purposes:

• Help determine the relative status of vital organs, including the heart, blood vessels, and lungs, which may be helpful in making many clinical decisions such as when to admit the patient to the hospital

• Establish a baseline (a record of initial measurements against which future recordings are compared)

• Monitor response to therapy, such as surgery and medication administration, as well as selected diagnostic tests.

• Observe for trends in the health status of the patient

• Determine the need for further evaluation, diagnostic testing, or intervention

Frequency of Vital Signs Measurement

In addition to acuity, certain procedures may determine the frequency with which vital signs are monitored. For example, patients undergoing a bronchoscopy (see Chapter 17) generally have baseline measurements taken before the procedure, at a maximum of 5-minute intervals during the procedure, and at similar intervals until they recover from moderate sedation and any lingering effects of the procedure. After surgery, vital signs are generally measured frequently to ensure the patient’s safety—often every 15 minutes for 2 hours, then every 30 minutes for 1 to 2 hours, then hourly until the patient is stable. The physician’s order in the chart is often written as “Vitals q15m × 2-4h, q30m × 4h, Q1H until stable, then per protocol.” Likewise, certain vital signs such as heart rate and respiratory rate should be monitored at a minimum before and after certain standard respiratory treatments like bronchodilator administration, to evaluate effectiveness of the treatment and for possible side effects.

Comparing Vital Signs Information

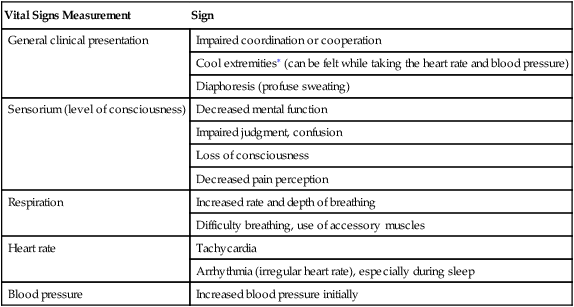

Clues to whether a patient’s condition may be stable or changing may be obtained by comparing changes in vital signs and other signs and symptoms. For example, patients who are not maintaining adequate blood oxygen levels develop specific changes in general appearance, level of consciousness, heart and respiratory rates, and blood pressure. Table 4-1 lists these common signs of developing acute hypoxemia (partial pressure of arterial oxygen [Pao2] <75 to 80 mm Hg).

TABLE 4-1

Signs of Hypoxemia Assessed During Vital Signs Measurement

| Vital Signs Measurement | Sign |

| General clinical presentation | Impaired coordination or cooperation |

| Cool extremities∗ (can be felt while taking the heart rate and blood pressure) | |

| Diaphoresis (profuse sweating) | |

| Sensorium (level of consciousness) | Decreased mental function |

| Impaired judgment, confusion | |

| Loss of consciousness | |

| Decreased pain perception | |

| Respiration | Increased rate and depth of breathing |

| Difficulty breathing, use of accessory muscles | |

| Heart rate | Tachycardia |

| Arrhythmia (irregular heart rate), especially during sleep | |

| Blood pressure | Increased blood pressure initially |

∗Temperature of the extremities, as well as diaphoresis, can be felt at the time the heart rate and blood pressure readings are obtained.

• Look at the patient: watch facial expressions, body movements, coordination, position, color, skin, anatomic landmarks, and effort to breathe or move.

• Listen to the patient: hear words, tones, sounds, rhythms, patterns, silence, feelings, and fears.

• Touch: feel moisture, temperature, air movement, change in temperature, muscle and skin tone, resistance, and quality of pulses.

• Analyze: collect information in a timely manner; compare it with normal values and the patient’s baseline and the disease procession. Mentally update this information whenever you are around the patient. Validate its accuracy. Does the information make sense? Is something wrong with the picture?

• Trend, trend, trend: what has changed about the patient? How has the patient changed and why? What has not changed? Why? What does it mean? Does the change indicate a need for immediate action?

General Clinical Presentation

• Cardiopulmonary distress is suggested by labored, rapid, irregular, or shallow breathing that may be accompanied by coughing, choking, wheezing, dyspnea, chest pain, or a bluish color (cyanosis) of the oral mucosa, lips, and fingers. The patient with cardiopulmonary distress often speaks in short, choppy sentences because of severe dyspnea.

• Anxiety is recognized by restlessness, fidgeting, tense looks, and difficulty communicating normally and may be accompanied by cool hands and sweaty palms.

• Pain is suggested by drawn features, moaning, shallow breathing, guarding (protecting the painful area), and refusal to deep-breathe or cough.

• Bleeding and loss of consciousness are signs of extreme distress that require immediate intervention.

A written description of these initial observations helps others involved in the patient’s care know how to plan care and relate to the patient’s needs. Usually, these descriptive statements are written in language everyone can understand (e.g., “J.C. is a cooperative, alert, well-nourished, 43-year-old man who appears younger than his stated age and exhibits no indication of distress. He shows no signs of acute or chronic illness and is admitted for …”). You may occasionally find that more specific terms for body types have been used in the written physical examination report. Box 4-1 lists and defines some of those terms.

Level of Consciousness (Sensorium)

Glasgow Coma Scale

Many systems for evaluating the patient’s level of consciousness have been developed. One such assessment tool is the Glasgow Coma Scale, which allows for objective evaluation based on behavioral response in three areas: motor function, verbal function, and eye-opening response. This scale can be quite useful in assessing trends in the neurologic function of patients who have been sedated, have received anesthesia, have suffered head trauma, or are near coma. The Glasgow Coma Scale is described in more detail in Chapter 6.