Chapter 4 Visual-aid questions

Format

The question types can be expected to vary, and trends change and evolve over time. The questions are prepared by the members of the VAQ Subcommittee of the Fellowship Examination Committee. The examiners are assigned questions to mark and so have no prior knowledge of the questions, which ensures that they are not marking in areas where they are experts. Each question is marked by two examiners who are blinded to each other’s marks until they make contact and agree on the final mark.

Preparation

Because the questions are prepared by FACEMs, it is reasonable to expect that images will be sourced from the departments they work in. As images and laboratory results become available, the ‘bank’ of questions will be developed to cover the curriculum. With this in mind and remembering the principle of what is ‘common’ and ‘commonly deadly’, it is possible to anticipate the important questions. Table 4.1 outlines likely VAQ topics that require most attention in your preparation. Many of these have featured in previous examinations and are likely to be used again. Other pathologies you need to be familiar with are presented in the right-hand column.

| Visual aid | Likely VAQ topics | Other VAQ topics |

| ECGs |

Sample VAQs can be sourced in a number of ways. A small number can be obtained from the College website or your DEMT, or your colleagues can write some for you, but the best way to prepare for this section of the examination is to write some VAQs yourself. We strongly encourage you to work your way through the topics in Table 4.1 to become familiar with the images and/or laboratory results associated with these conditions. The process of identifying suitable material that lends itself well to VAQs is excellent exam preparation.

As with other sections of the exam, you can incorporate your day-to-day practice into your preparation for the VAQ section. Each time a nurse, medical student, junior doctor or consultant asks you to interpret an ECG, an X-ray or a pathology result or you see a patient where the diagnosis can be made on initial inspection, you have an opportunity to practise your VAQ answering skills.

On the day

Reading time

No writing is allowed during the 10 minutes of reading time prior to the commencement of the exam. Use this time to read through the whole paper carefully and plan your overall structure for each question. Decide which questions you are more likely to be able to answer well. It is best to decide before the examination whether you will tackle the questions in the order they appear or start ‘easy’ and finish ‘hard’. In either case, it is imperative you have a good method of timekeeping so that you do not run out of time and miss answering some questions.

Sample VAQs

To help with your preparation, some worked sample VAQs have been provided. Draw on these as a framework to develop your own practice VAQs, using the topics in Table 4.1 as a guide. In addition, a range of VAQ props are presented as ‘problems’ for you to ponder with sample questions. We suggest that you use these to develop further questions using standard terminology and then write full answers using the templates suggested in Table 3.2 (see pages 25–27). Suggested answers to some of these questions are provided towards the end of the chapter. A broad range of material is included. Some items are presented to stimulate you to cover topics that may otherwise be glossed over (e.g. therapies and equipment that are now less likely to be assessed as VAQs, but are most easily studied using this format and may be examined in other sections of the exam).

VAQ 1

Sample answer

The image shows an open fracture/dislocation of the right ankle.

Management

VAQ 2

| T | 36.8°C |

| P | 89/min |

| GCS | 15/15 |

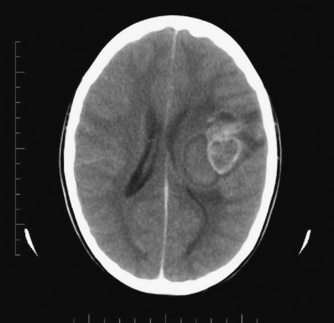

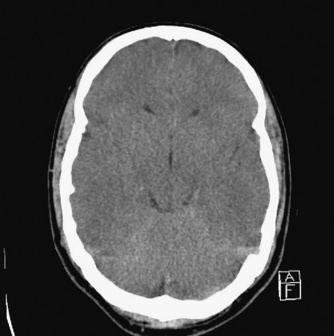

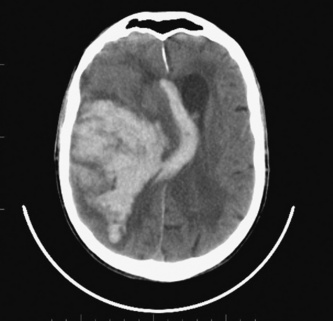

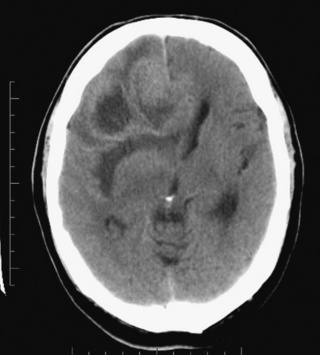

(a) Describe and interpret this image from her contrast CT brain scan. (50%)

Sample answer

VAQ 3

| Value | Normal range | |

| pH | 6.80 | 7.32–7.43 |

| pCO2 | 36 mmHg | 37–50 mmHg |

| pO2 | 47 mmHg | 36–44 mmHg |

| Bicarbonate | 6 mmol/L | 22–28 mmol/L |

| Base excess | –28 mmol/L | –3 to 3 mmol/L |

| Sodium | 136 mmol/L | 134–146 mmol/L |

| Potassium | 6.7 mmol/L | 3.4–5.0 mmol/L |

| Chloride | 90 mmol/L | 98–108 mmol/L |

| Urea | 13.8 mmol/L | 3.0–8.0 mmol/L |

| Creatinine | 210 μmol/L | < 105 μmol/L |

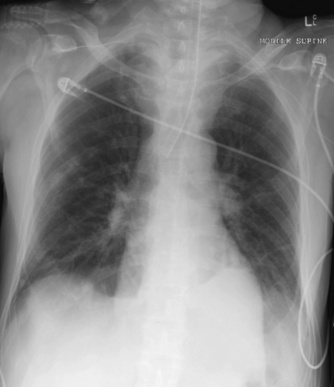

| Glucose | 54.0 mmol/L | 3.0–5.4 mmol/L |

Sample answer

Listed investigations

Venous blood gas and U&Es show:

Interpretation

VAQ 4

VAQ 5

VAQ 6

VAQ 8

| O2via nasal cannulae 2 L/min | Value | Reference range |

| pH | 7.13 | 7.35–7.45 |

| CO2 | 7 mmHg | 36–45 mmHg |

| O2 | 146 mmHg | 8–110 mmHg |

| Bicarbonate | < 3 mmol/L | 21–28 mmol/L |

| Glucose | 15.7 mmol/L | 3.0–5.4 mmol/L |

| Lactate | 4.3 mmol/L | < 1.3 mmol/L |

| Sodium | 142 mmol/L | 134–146 mmol/L |

| Potassium | 5.2 mmol/L | 3.4–5.0 mmol/L |

| Chloride | 103 mmol/L | 98–108 mmol/L |

| Urea | 2.4 mmol/L | 3.0–8.0 mmol/L |

| Creatinine | 107 μmol/L | < 120 μmol/L |

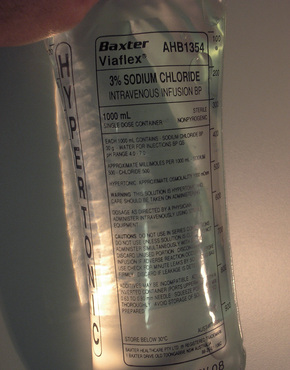

Additional VAQ practice material

Start by describing the key findings demonstrated by each image, as this is frequently requested in the exam.

Problem 4.12

Problem 4.15

| Parameter | Value | Reference range |

| Sodium | 135 mmol/L | 135–145 mmol/L |

| Potassium | 6.3 mmol/L | 3.5–5 mmol/L |

| Chloride | 96 mmol/L | 101–109 mmol/L |

| Bicarbonate | 15 mmol/L | 22–32 mmol/L |

| Urea | 19 mmol/L | 3–8 mmol/L |

| Creatinine | 79 μmol/L | 50–120 μmol/L |

| Glucose | 9 mmol/L | 3–7.8 mmol/L |

| Osmolality | 335 mosm/kg | 280–290 mosm/kg |

| Total BR | 10 mmol/L | < 20 mmol/L |

| ALT | 38 mmol/L | < 45 mmol/L |

| AST | 450 mmol/L | < 40 mmol/L |

| GGT | 40 mmol/L | < 50 mmol/L |

| ALK PHOS | 85 mmol/L | 30–100 mmol/L |

| CK | 50,000 U/L | 50–150 U/L |

| LDH | 658 mmol/L | 110–250 mmol/L |

| Corrected calcium | 2.1 mmol/L | 2.2–2.65 mmol/L |

| Phosphate | 3.01 mmol/L | 0.7–1.4 mmol/L |

What is the most likely diagnosis? What are the causes of this problem?

Problem 4.26

| Parameter | Value | Reference range |

| Hb | 78 g/L | 115–160 g/L |

| RCC | 2.23 × 1012/L | 3.80–4.80 × 1012/L |

| Hct | 0.23 | 0.37–0.47 |

| MCV | 102 fL | 80–100 fL |

| MCH | 35.2 pg | 27.0–32.0 pg |

| MCHC | 347 g/L | 320–360 g/L |

| RDW | 20.0 | 9.0–15.0 |

| White cell count | 158.08 × 109/L | 4.00–11.00 × 109/L |

| Neutrophils | 50.6 × 109/L | 2.00–7.50 × 109/L |

| Lymphocytes | 4.74 × 109/L | 1.20–4.00 × 109/L |

| Monocytes | 4.74 × 109/L | 0.20–1.00 × 109/L |

| Eosinophils | 6.32 × 109/L | 0.00–0.50 × 109/L |

| Metamyelocytes | 30.0 × 109/L | |

| Myelocytes | 30.0 × 109/L | |

| Promyelocytes | 31.6 × 109/L | |

| Nucleated RBC | 4/100 WBC | |

| Platelet count | 70 × 109/L | 150–400 × 109/L |

Problem 4.27

| Parameter | Value | Reference range |

| Hb | 59 g/L | 110–145 g/L |

| RCC | 1.93 × 1012/L | 3.90–6.00 × 1012/L |

| Hct | 0.16 | 0.34–0.44 |

| MCV | 92 fL | 72–87 fL |

| MCH | 30.4 pg | 24.0–32.0 pg |

| MCHC | 370 g/L | 20–360 g/L |

| RDW | 12.7 | 9.0–15.0 |

| White cell count | 13.70 × 109/L | 5.00–17.00 × 109/L |

| Neutrophils | 9.62 × 109/L | 1.50–8.50 × 109/L |

| Lymphocytes | 2.52 × 109/L | 1.50–9.50 × 109/L |

| Monocytes | 1.32 × 109/L | 0.20–1.00 × 109/L |

| Eosinophils | 0.19 × 109/L | 0.00–0.80 × 109/L |

| Basophils | 0.05 × 109/L | 0.00–0.20 × 109/L |

| Platelet count | 256 × 109/L | 150–400 × 109/L |

| Bilirubin | 93 μmol/L | < 20 μmol/L |

Answers to additional VAQs

Problem 4.1: horizontal beam Swimmer’s view of cervical spine

Expected knowledge

Results of physical examination

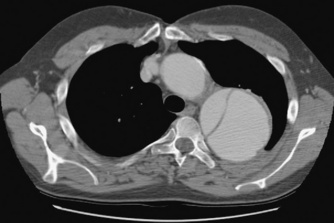

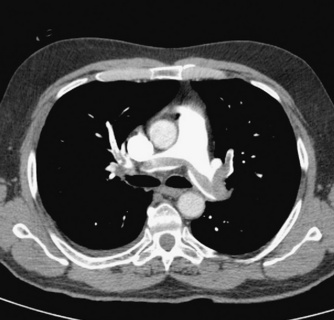

Problem 4.2: CT scan of chest with contrast — mediastinal window

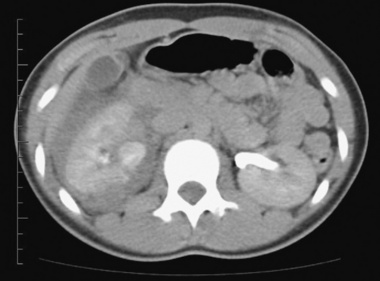

Problem 4.3: CT scan of abdomen

Expected knowledge

Possible causes

Problem 4.4: CT pulmonary angiogram

Problem 4.6: CT scan of head

Expected knowledge

Possible causes

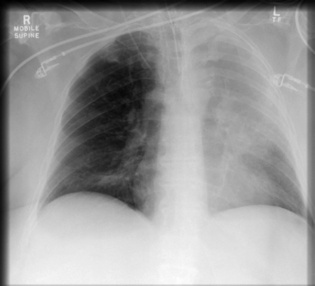

Problem 4.8: mobile supine chest X-ray

Problem 4.9: CT scan of head

Problem 4.10: mobile supine abdominal X-ray

Problem 4.11: erect PA chest X-ray

Key findings

Expected knowledge

Management implications

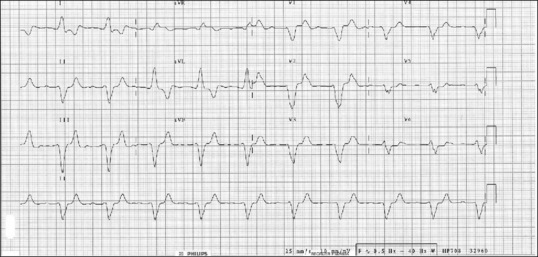

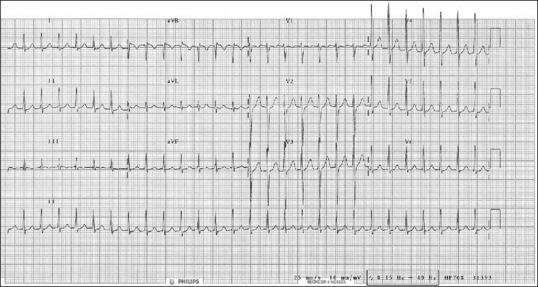

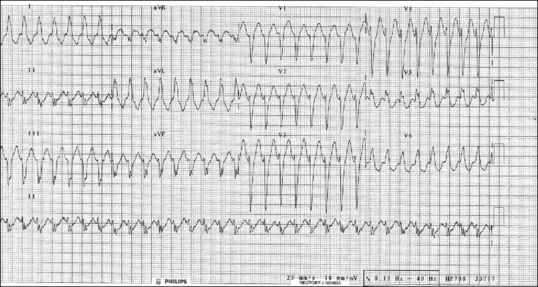

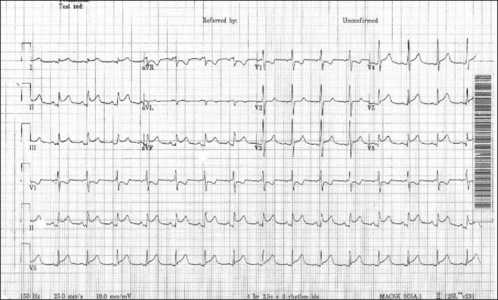

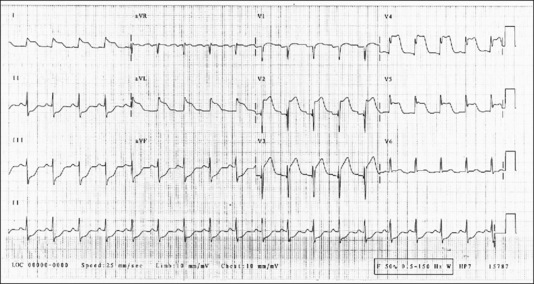

Problem 4.13: ECG

Expected knowledge

Differentiating between the two possibilities

Problem 4.16: photograph of trauma patient

Expected knowledge

Management priorities

Problem 4.17: photograph of foot

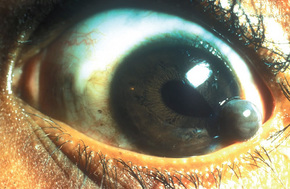

Problem 4.18: photograph of eye

Problem 4.20: photograph of child

Key findings

Problem 4.22: chest X-ray

Expected knowledge

Management

Problem 4.24: CT scan of head

Expected knowledge

Management

The answer should acknowledge that the prognosis is poor.

Problem 4.25: CT scan of abdomen

Problem 4.26: blood profile

Problem 4.27: blood profile

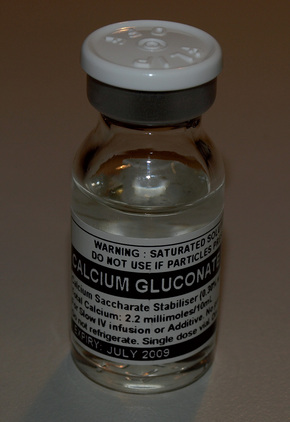

Problem 4.28: photograph

Problem 4.29: photograph

Expected knowledge

Usage

Problem 4.30: photograph

Expected knowledge

Potential uses in ED

Problem 4.31: chest X-ray

Expected knowledge

Management

Problem 4.32: CT scan of head

Key findings

Expected knowledge

Indications for thrombolysis in stroke

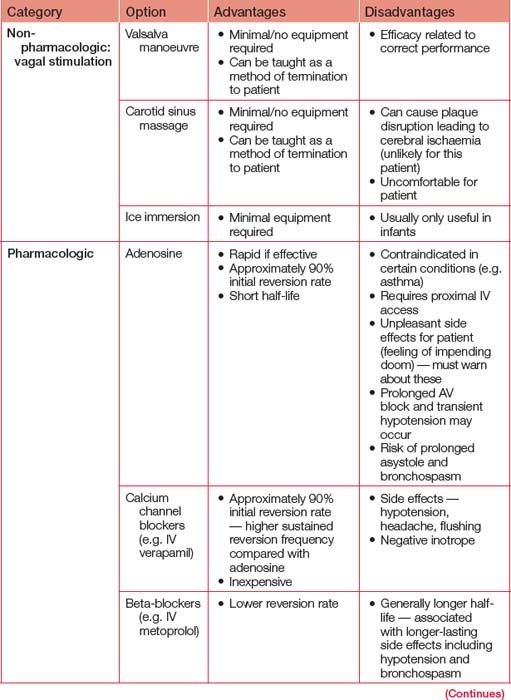

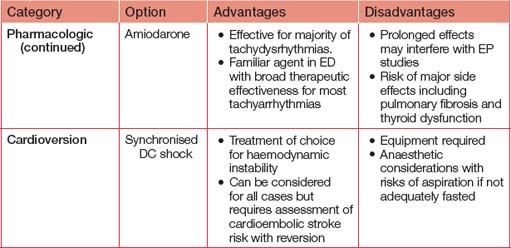

Problem 4.33: CT scan of chest

Expected knowledge

Clinical significance

Problem 4.34: ECG

Key findings

Expected knowledge

Pharmacological agents that may benefit this patient

Problem 4.35: abdominal X-ray

Key findings

Problem 4.36: chest X-ray

Key findings

Problem 4.37: photograph

Problem 4.38: photograph

Expected knowledge

How the device works

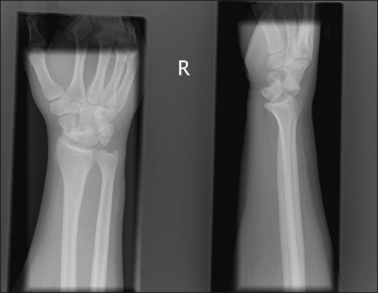

Problem 4.39: wrist X-rays

Expected knowledge

Management

Problem 4.40: photograph

Problem 4.41: photograph

Acid-base disorders

The approach to take is as follows:

Terminology

Interpretation

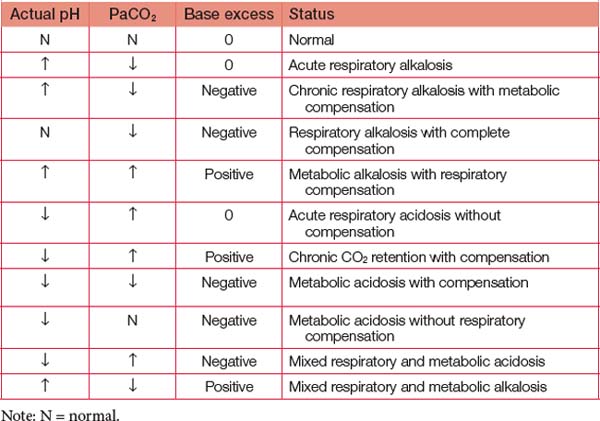

By addressing the combined criteria of pH, PaCO2 and any of the metabolic markers, it is possible to rapidly determine the presence of simple or compensated disorders as well as the primary and compensatory components (see Table 4.2). Where both metabolic and respiratory components are driving pH in the same direction, the disorder is termed ‘mixed’. The most fascinating case in clinical practice is salicylate toxicity, which can cause all four primary disorders to various degrees.

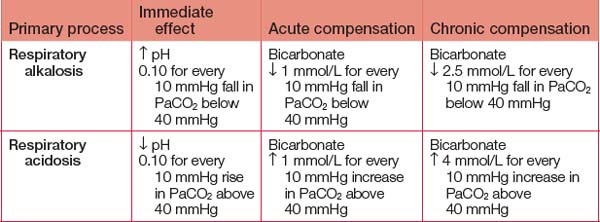

Acute and chronic compensation

Metabolic compensation

When presented with a primary respiratory disorder, it is possible to determine whether the metabolic compensation is acute or chronic and whether it appears appropriate. Metabolic changes take time to develop and should be to the degree indicated in Table 4.3. When the actual bicarbonate or base excess differs from that expected, it is likely that a third disorder is also present. The most common ‘triple disorders’ are when patients with chronic respiratory acidosis develop an acute metabolic acidosis from infection or develop an acute respiratory acidosis from exhaustion or, less commonly, loss of hypoxic drive.

If you overcome your apprehension of the Siggaard-Andersen nomogram and take some time analysing its features, you will see how base excess is derived and even how the less prominent buffering effect of haemoglobin is included (Bohr and Haldane effects).