Chapter 107 Violent Behavior

The World Health Organization (WHO) recognizes violence as a leading worldwide public health problem and defines violence as “The intentional use of physical force or power, threatened or actual, against oneself, another person, or against a group or community that either results in or has a high likelihood of resulting in injury, death, psychologic harm, maldevelopment or deprivation” (Chapter 36). Youths may be perpetrators of violence, victims of violence, or observers of violence with varying severity of impact on the individual, family, or larger community. A number of risk factors have been identified that may increase the risk of a youth to engage in violence such as poverty, substance abuse, mental health disorders, and poor family functioning.

Epidemiology

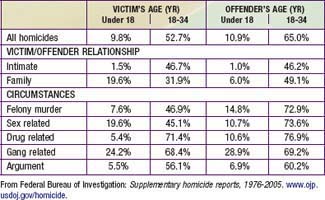

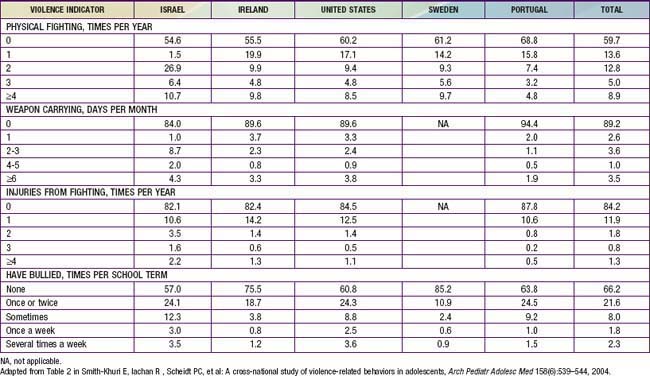

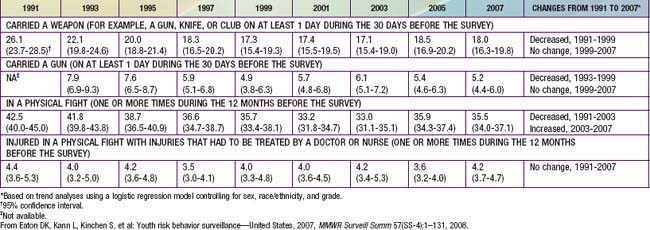

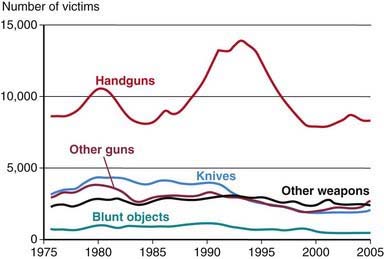

In 2006, homicide in the USA was the second leading cause of death for 10-24 yr olds totaling 5,958 deaths, which were largely males (87%) killed by a handgun (84%) in a gang-related incident (Table 107-1). The WHO reports that other than the USA, where the youth and young adult homicide rate was 11 per 100,000, most countries with homicide rates above 10 per 100,000 are developing nations or countries with rapid socioeconomic changes. However, while rates of violent deaths among adolescents are higher in the USA compared to other developed countries, rates are increasing; in Israel, France, and Norway, firearms are the second leading mechanism of death in 15-24 yr olds. Although the prevalence of behaviors that contribute to violence has decreased from 1991 to 2007, fighting and weapon carrying remain prevalent among U.S. youth (Table 107-2). In 2007, 668,000 youths were treated in U.S. emergency departments for violence-related injuries such as stab wounds, gunshot wounds, broken bones, and lacerations. The rate of homicide by handgun is considerably higher than homicide by other weapon type, suggesting that access to firearms may play a major role in youth injuries and deaths (Fig. 107-1). A cross-sectional, nationally representative survey of ~21,000 youth at ages 11.5, 13.5, and 15.5 yr in 5 countries (Ireland, Israel, Portugal, Sweden, and the USA) revealed that the rates of fighting, weapon carrying, and fighting injury were similar among the countries while bullying frequency varied widely, from 15% in Sweden to 43% in Israel (Table 107-3).

Table 107-2 TRENDS (% OF YOUTH) IN THE PREVALENCE OF BEHAVIORS THAT CONTRIBUTE TO VIOLENCE (1991-2007)

Figure 107-1 Number of victims of homicides by weapon type, 1976-2005.

(From U.S. Department of Justice, Office of Justice Programs, Bureau of Justice Statistics: Homicide trends in the U.S. www.ojp.usdoj.gov/bjs/homicide/teens.htm. Accessed June 2009.)

Advancements of technology are being used by youths as a vehicle to inflict aggression of a different nature. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) defines electronic aggression as any type of harassment or bullying (teasing, telling lies, making fun of someone, making rude or mean comments, spreading rumors, or making threatening or aggressive comments) that occurs through e-mail, chat rooms, instant messaging, blogs, test messaging or videos or photos posted on a website or sent via cell phone (Chapter 36.1). In 2005, 9% of youth surveyed reported being a victim of online harassment via instant messaging (67%), e-mail (24%), and text messages (15%). Of the youth surveyed, 7-14% reported being both a victim and a perpetrator, suggesting that there is a related behavioral link between the 2 roles.

Clinical Manifestations

Inability to master prosocial skills such as the establishment and maintenance of positive family and peer relations and poor resolution of conflict may put adolescents with these disorders at higher risk of physical violence and other risky behaviors. Conduct disorder and oppositional defiant disorder are specific psychiatric diagnoses whose definitions are associated with violent behavior (Table 107-4). They occur co-morbidly with other disorders such as attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and increase an adolescent’s vulnerability for juvenile delinquency, substance use or abuse, sexual promiscuity, adult criminal behavior, incarceration, and antisocial personality disorder. Other co-occurring risk factors for youth violence include use of anabolic steroids, gang tattoos, belief in one’s premature death, preteen alcohol use, and placement in a juvenile detention center.

Table 107-4 OPPOSITIONAL DEFIANT DISORDER, CONDUCT DISORDER, AND JUVENILE DELINQUENCY

| PSYCHIATRIC DISORDER LABELS | LEGAL LABEL JUVENILE DELINQUENCY | |

|---|---|---|

| Oppositional Defiant Disorder | Conduct Disorder | |

| Recurrent pattern of negativistic, defiant, disobedient, and hostile behavior toward authority figures that has a significant adverse effect on functioning (e.g., social, academic, occupational) | Repetitive and persistent pattern of behavior that violates the basic rights of others or major age-appropriate societal norms or rules | Offenses that are illegal because of age; illegal acts |

| Examples: losing temper; arguing with adults; defying or refusing to comply with request or rules of adults; annoying behavior; blaming others; and being irritable, spiteful, resentful | Examples: physical fighting, deceitfulness, stealing, destruction of property, threatening or causing physical harm to people or animals, driving without a license, prostitution, rape (even if not adjudicated in the legal system) | Examples: single or multiple instances of being arrested or adjudicated for any of the following: stealing, destruction of property, threatening or causing physical harm to people or animals, driving without a license, prostitution, rape |

| Diagnosed by a mental health clinician | Diagnosed by a mental health practitioner | Adjudicated in the legal system |

From Greydanus DE, Pratt HD, Patel DR, et al: The rebellious adolescent, Pediatr Clin North Am 44:1460, 1997.

Diagnosis

The assessment of an adolescent at risk, or with a history of violent behavior or victimization should be a part of the health maintenance visit of all adolescents. The answers to questions about recent history of involvement in a physical fight, carrying a weapon, or firearms in the household, as well as concerns that the adolescent may have about his or her personal safety may suggest a problem requiring a more in-depth evaluation. The FISTS mnemonic provides guidance for structuring the assessment (Table 107-5). The additional factors of physical or sexual abuse, serious problems at school, poor school performance and attendance, multiple incidents of trauma, substance use, and symptoms associated with mental disorders are indications for evaluation by a mental health professional. In a situation of acute trauma, assault victims are not always forthcoming about the circumstances of their injuries for fear of retaliation or police involvement. Stabilization of the injury or the gathering of forensic evidence in sexual assault is the treatment priority; however, once this is achieved, addressing a more comprehensive set of issues surrounding the assault is appropriate.

Table 107-5 FISTS MNEMONIC TO ASSESS AN ADOLESCENT’S RISK OF VIOLENCE

F: Fighting (How many fights were you in last year? What was the last?)

I: Injuries (Have you ever been injured? Have you ever injured someone else?)

S: Sex (Has your partner hit you? Have you hit your partner? Have you ever been forced to have sex?)

T: Threats (Has someone with a weapon threatened you? What happened? Has anything changed to make you feel safer?)

S: Self-defense (What do you do if someone tries to pick a fight? Have you carried a weapon in self-defense?)

From Knox L: Connecting the dots to prevent youth violence: a training and outreach guide for physicians and other health professionals, Chicago, 2002, American Medical Association, p 24.

Prevention

The WHO report recognizes a multifactorial approach to prevention: individual approaches, relationship approaches, community approaches, and societal approaches (Table 107-6). Individual approaches concentrate on changing attitudes and behaviors to avoid aggressive and violent behavior as well as teaching coping strategies and nonviolent conflict resolution for all children as well as youths who have already displayed some violent tendencies. Relationship approaches focus more on victims, families, and peer relationships, especially those with the potential to trigger aggressive or violent responses. Solutions include improving skills in coping or problem solving in recent perceived crises, interpersonal conflicts, and close relationships. Family-based programs provide training for parents in areas of effective communication, child development, and solving problems in nonviolent methods. Community-based approaches raise public awareness in an effort to stimulate action by community members to reduce violence and protect vulnerable community members. Universal school-based violence prevention programs have been found to be effective in reducing violent and aggressive behaviors. Interventions beginning as early as preschool have been found to have positive outcomes years later. Societal approaches include broader advocacy and legislative actions, as well as changing the cultural norm toward violent behaviors. A specific prevention strategy can incorporate several approaches, such as the handgun/firearm prevention recommendations that include gun-lock safety, public education, and legislative advocacy. Other efforts are directed toward establishing a national database to track and define the problem of youth violence. The National Violent Death Reporting System (NVDRS) collects and analyzes violent death data from 17 states and aims to improve surveillance of current trends, to share information state to state, to build partnerships among state and community organizations, and to develop and implement prevention and intervention programs. Ultimately the NVDRS will be expanded to include all 50 states. The CDC characterizes specific successful programs and summarizes program content on its website (www.cdc.gov).

American Academy of Pediatrics, Stirling JJr, et al. Understanding the behavioral and emotional consequences of child abuse. Committee on Child Abuse and Neglect and Section on Adoption and Foster Care. Pediatrics. 2008;122:667-673. Erratum in: Pediatrics 123:197, 2009

Beaver KM, Vaughn MG, Delisi M, et al. Anabolic-androgenic steroid use and involvement in violent behavior in a nationally representative sample of young adult males in the United States. Am J Public Health. 2008;98:2185-2187.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. CDC overview: electronic media and youth violence: a CDC issue brief for educators and caregivers. www.cdc.gov/ncipc/dvp/yvp/electronic_aggression.htm.

Champion H, Wagoner K. Adolescent date fighting victimization and perpetration from a multi-community samples: associations with substance use and other violent victimization and perpetration. Int J Adolesc Med Health. 2008;20:419-429.

Council on Communications and Media. From the American Academy of Pediatrics: policy statement–impact of music, music lyrics, and music videos on children and youth. Pediatrics. 2009;124:1488-1494.

DuRant RH, Champion H. The relationship between watching professional wrestling on television and engaging in date fighting among high school students. Pediatrics. 2006;118:e265-e272.

Elbogen EB, Johnson SC. The intricate link between violence and mental disorder: results from the national epidemiologic survey on alcohol and related conditions. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2009;66:152-161.

Hahn R, Fuqua-Whitley D, Wethington H, et al. The effectiveness of universal school-based programs of the prevention of violent and aggressive behavior. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2007;56(RR-7):1-12.

Herrenkohl TI, Hill KG. Developmental trajectories of family management and risk for violent behavior in adolescence. J Adolesc Health. 2006;39:206-213.

Karch DL, Dahlberg LL, Patel N, et al. Surveillance for violent deaths—National Violent Death Reporting System, 16 States, 2006. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2009;58(1):1-44.

Ko CH, Yen JY, Chen CS, et al. Predictive values of psychiatric symptoms for internet addiction in adolescents. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2009;163:937-943.

Komar D, Lathrop S. Tattoo types and frequencies in New Mexican white Hispanics and white non-Hispanic: autopsy data from homicidal and accidental deaths, 2002-2005. Am J Forensic Med Pathol. 2008;29:285-289.

McCall PL, Parker KF. The dynamic relationship between homicide rates and social, economic, and political factors from 1970 to 2000. Soc Sci Res. 2008;37:721-735.

Molnar BE, Browne A. Violent behavior by girls reporting violent victimization: a protective study. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2005;159:731-739.

Moreno MA, VanderStoep A, Parks MR, et al. Reducing at-risk adolescents’ display of risk behavior on a social networking web site. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2009;163:35-40.

Parker-Higgerson HK, Perumean-Chaney SE, Bartolucci AA, et al. The evaluation of school-based violence prevention programs: a meta-analysis. J Sch Health. 2008;78(9):465-479.