Vibrio, Aeromonas, Chromobacterium, and Related Organisms

1. Describe the general characteristics of the organisms discussed in this chapter, including natural habitat, route of transmission, Gram stain reactions, and cellular morphology.

2. Describe the media used to isolate Vibrio spp. and the organisms’ colonial appearance.

3. Explain the physiologic activity of the cholera toxin and its relationship to the pathogenesis of the organism.

4. Describe the clinical significance of Aeromonas spp., Chromobacterium sp., and Vibrio spp. other than Vibrio cholerae.

5. Correlate the patient’s signs and symptoms and laboratory data to identify an infectious agent.

Epidemiology

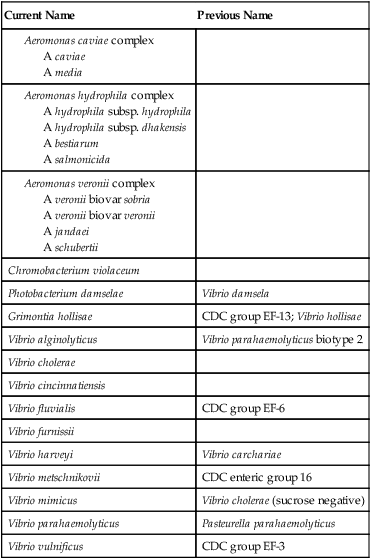

Many aspects of the epidemiology of Vibrio spp., Aeromonas spp., and C. violaceum are similar (Table 26-1). The primary habitat for most of these organisms is water; generally, brackish or marine water for Vibrio spp., freshwater for Aeromonas spp., and soil or water for C. violaceum. Aeromonas spp. may also be found in brackish water or marine water with a low salt content. None of these organisms are considered part of the normal human flora. Transmission to humans is by ingestion of contaminated water, fresh produce, meat, dairy products, or seafood or by exposure of disrupted skin and mucosal surfaces to contaminated water.

TABLE 26-1

| Species | Habitat (Reservoir) | Mode of Transmission |

| Vibrio cholerae | Niche outside of human gastrointestinal tract between occurrence of epidemics and pandemics is uncertain; may survive in a dormant state in brackish or saltwater; human carriers also are known but are uncommon | Fecal-oral route, by ingestion of contaminated washing, swimming, cooking, or drinking water; also by ingestion of contaminated shellfish or other seafood |

| V. alginolyticus | Brackish or saltwater | Exposure to contaminated water |

| V. cincinnatiensis | Unknown | Unknown |

| Photobacterium damsela | Brackish or saltwater | Exposure of wound to contaminated water |

| V. fluvialis | Brackish or saltwater | Ingestion of contaminated water or seafood |

| V. furnissii | Brackish or saltwater | Ingestion of contaminated water or seafood |

| Grimontia hollisae | Brackish or saltwater | Ingestion of contaminated water or seafood |

| V. metschnikovii | Brackish, salt and freshwater | Unknown |

| V. mimicus | Brackish or saltwater | Ingestion of contaminated water or seafood |

| V. parahaemolyticus | Brackish or saltwater | Ingestion of contaminated water or seafood |

| V. vulnificus | Brackish or saltwater | Ingestion of contaminated water or seafood |

| Aeromonas spp. | Aquatic environments around the world, including freshwater, polluted or chlorinated water, brackish water and, occasionally, marine water; may transiently colonize gastrointestinal tract; often infect various warm- and cold-blooded animal species | Ingestion of contaminated food (e.g., dairy, meat, produce) or, water; exposure of disrupted skin or mucosal surfaces to contaminated water or soil; traumatic inoculation of fish fins and or fishing hooks |

| Chromobacterium violaceum | Environmental, soil and water of tropical and subtropical regions. Not part of human flora | Exposure of disrupted skin to contaminated soil or water |

Pathogenesis and Spectrum of Disease

As a notorious pathogen, V. cholerae elaborates several toxins and factors that play important roles in the organism’s virulence. Cholera toxin (CT) is primarily responsible for the key features of cholera (Table 26-2). Release of this toxin causes mucosal cells to hypersecrete water and electrolytes into the lumen of the gastrointestinal tract. The result is profuse, watery diarrhea, leading to dramatic fluid loss. The fluid loss results in severe dehydration and hypotension that, without medical intervention, frequently lead to death. This toxin-mediated disease does not require the organism to penetrate the mucosal barrier. Therefore, blood and the inflammatory cells typical of dysenteric stools are notably absent in cholera. Instead, “rice water stools,” composed of fluids and mucous flecks, are the hallmark of cholera toxin activity.

TABLE 26-2

Pathogenesis and Spectrum of Diseases

| Species | Virulence Factors | Spectrum of Disease and Infections |

| Vibrio cholerae | Cholera toxin; zonula occludens (Zot) toxin (enterotoxin); accessory cholera enterotoxin (Ace) toxin; O1 and O139 somatic antigens, hemolysin/cytotoxins, motility, chemotaxis, mucinase, and toxin coregulated pili (TCP) pili. | Cholera: profuse, watery diarrhea leading to dehydration, hypotension, and often death; occurs in epidemics and pandemics that span the globe. May also cause nonepidemic diarrhea and, occasionally, extra intestinal infections of wounds, respiratory tract, urinary tract, and central nervous system |

| V. alginolyticus | Specific virulence factors for the non–V. cholerae species are uncertain. | Ear infections, wound infections; rare cause of septicemia; involvement in gastroenteritis is uncertain |

| V. cincinnatiensis | Rare cause of septicemia | |

| P. damsela | Wound infections and rare cause of septicemia | |

| V. fluvialis | Gastroenteritis | |

| V. furnissii | Rarely associated with human infections | |

| Grimontia hollisae | Gastroenteritis; rare cause of septicemia | |

| V. metschnikovii | Rare cause of septicemia; involvement in gastroenteritis is uncertain | |

| V. mimicus | Gastroenteritis; rare cause of ear infection | |

| V. vulnificus | Wound infections and septicemia; involvement in gastroenteritis is uncertain | |

| Aeromonas spp. | Aeromonas spp. produce various toxins and factors, but their specific role in virulence is uncertain. | Gastroenteritis, wound infections, bacteremia, and miscellaneous other infections, including endocarditis, meningitis, pneumonia, conjunctivitis, and osteomyelitis |

| Chromobacterium violaceum | Endotoxin, adhesins, invasins and cytolytic proteins have been described. | Rare but dangerous infection. Begins with cellulitis or lymphadenitis and can rapidly progress to systemic infection with abscess formation in various organs and septic shock |

V. cholerae produces several other toxins and factors, but the exact role of these in disease is still uncertain (see Table 26-2). To effectively release toxin, the organism first must infiltrate and distribute itself along the cells lining the mucosal surface of the gastrointestinal tract. Motility and chemotaxis mediate the distribution of organisms, and mucinase production allows penetration of the mucous layer. Toxin coregulated pili (TCP) provide the means by which bacilli attach to mucosal cells for release of cholera toxin.

Laboratory Diagnosis

Specimen Collection and Transport

Because no special considerations are required for isolation of these genera from extraintestinal sources, the general specimen collection and transport information provided in Table 5-1 is applicable. However, stool specimens suspected of containing Vibrio spp. should be collected and transported only in Cary-Blair medium. Buffered glycerol saline is not acceptable, because glycerol is toxic for vibrios. Feces is preferable, but rectal swabs are acceptable during the acute phase of diarrheal illness.

Direct Detection Methods

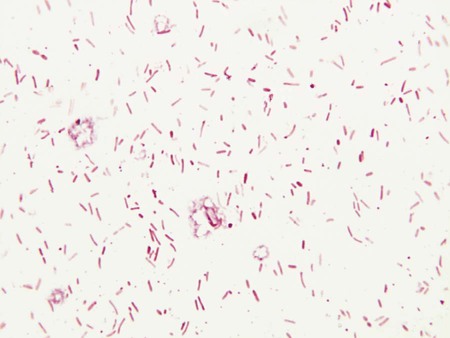

Microscopically, vibrios are gram-negative, straight or slightly curved rods (Figure 26-1). When stool specimens from patients with cholera are examined using dark-field microscopy, the bacilli exhibit characteristic rapid darting or shooting-star motility. However, direct microscopic examination of stools by any method is not commonly used for laboratory diagnosis of enteric bacterial infections.

Cultivation

Media of Choice

Incubation Conditions and Duration

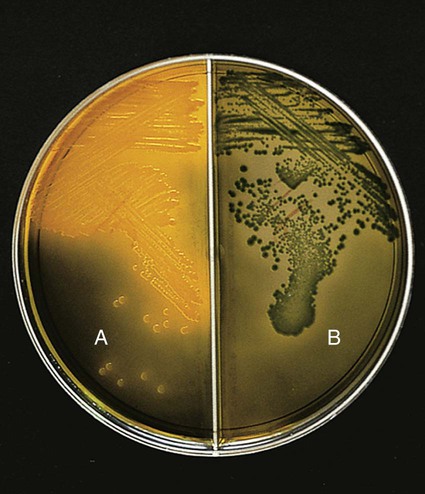

These organisms produce detectable growth on 5% sheep blood and chocolate agars when incubated at 35°C in carbon dioxide or ambient air for a minimum of 24 hours. MacConkey and TCBS agars only should be incubated at 35°C in ambient air. The typical violet pigment of C. violaceum colonies (Figure 26-2) is optimally produced when cultures are incubated at room temperature (22°C).

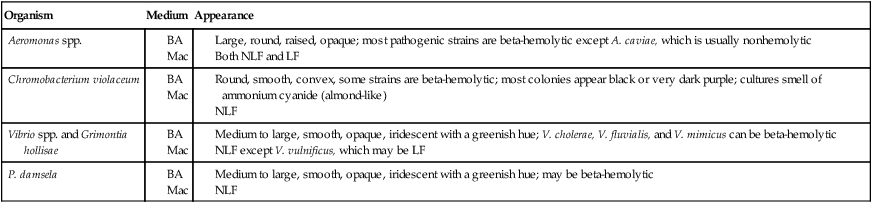

Colonial Appearance

Table 26-3 describes the colonial appearance and other distinguishing characteristics (e.g., hemolysis and odor) of each genus on 5% sheep blood and MacConkey agars. The appearance of Vibrio spp. on TCBS is described in Table 26-4 and shown in Figure 26-3.

BA, 5% sheep blood agar; Mac, MacConkey agar; LF, lactose fermenter, NLF, non–lactose fermenter.

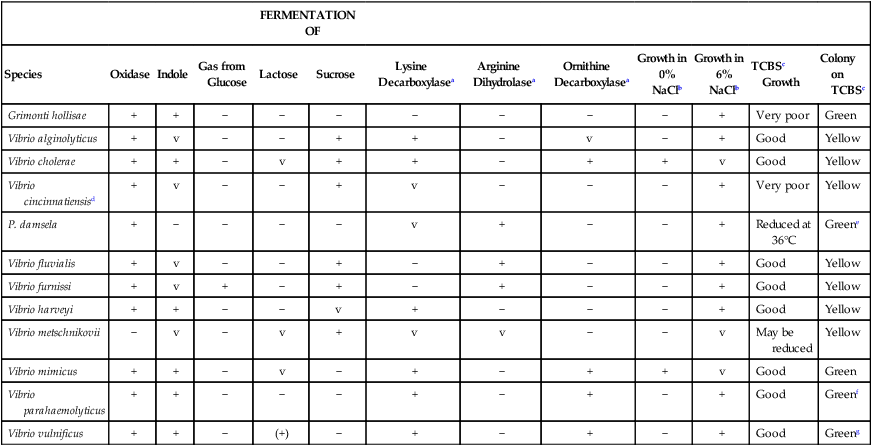

TABLE 26-4

Key Biochemical and Physiologic Characteristics of Vibrio spp. and Grimontia hollisae

| FERMENTATION OF | ||||||||||||

| Species | Oxidase | Indole | Gas from Glucose | Lactose | Sucrose | Lysine Decarboxylasea | Arginine Dihydrolasea | Ornithine Decarboxylasea | Growth in 0% NaClb | Growth in 6% NaClb | TCBSc Growth | Colony on TCBSc |

| Grimonti hollisae | + | + | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | + | Very poor | Green |

| Vibrio alginolyticus | + | v | − | − | + | + | − | v | − | + | Good | Yellow |

| Vibrio cholerae | + | + | − | v | + | + | − | + | + | v | Good | Yellow |

| Vibrio cincinnatiensisd | + | v | − | − | + | v | − | − | − | + | Very poor | Yellow |

| P. damsela | + | − | − | − | − | v | + | − | − | + | Reduced at 36°C | Greene |

| Vibrio fluvialis | + | v | − | − | + | − | + | − | − | + | Good | Yellow |

| Vibrio furnissi | + | v | + | − | + | − | + | − | − | + | Good | Yellow |

| Vibrio harveyi | + | + | − | − | v | + | − | − | − | + | Good | Yellow |

| Vibrio metschnikovii | − | v | − | v | + | v | v | − | − | v | May be reduced | Yellow |

| Vibrio mimicus | + | + | − | v | − | + | − | + | + | v | Good | Green |

| Vibrio parahaemolyticus | + | + | − | − | − | + | − | + | − | + | Good | Greenf |

| Vibrio vulnificus | + | + | − | (+) | − | + | − | + | − | + | Good | Greeng |

V, Variable; +, >90% of strains are positive; −, >90% of strains are negative; (+), delayed.

a1% NaCl added to enhance growth.

bNutrient broth with 0% or 6% NaCl added.

Approach to Identification

The ability of most commercial identification systems to accurately identify Aeromonas organisms to the species level is limited and uncertain, and with some kits, difficulty arises in separating Aeromonas spp. from Vibrio spp. Therefore, identification of potential pathogens should be confirmed using conventional biochemical tests or serotyping. Tables 26-4 and 26-5 show several characteristics that can be used to presumptively group Vibrio spp., Aeromonas spp., and C. violaceum.

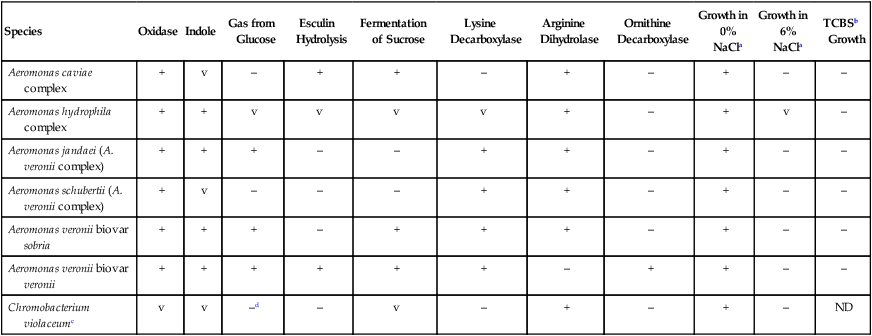

TABLE 26-5

Key Biochemical and Physiologic Characteristics of Aeromonas spp., P. shigelloides, and C. violaceum

| Species | Oxidase | Indole | Gas from Glucose | Esculin Hydrolysis | Fermentation of Sucrose | Lysine Decarboxylase | Arginine Dihydrolase | Ornithine Decarboxylase | Growth in 0% NaCla | Growth in 6% NaCla | TCBSb Growth |

| Aeromonas caviae complex | + | v | – | + | + | – | + | – | + | – | – |

| Aeromonas hydrophila complex | + | + | v | v | v | v | + | – | + | v | – |

| Aeromonas jandaei (A. veronii complex) | + | + | + | – | – | + | + | – | + | – | – |

| Aeromonas schubertii (A. veronii complex) | + | v | – | – | – | + | + | – | + | – | – |

| Aeromonas veronii biovar sobria | + | + | + | – | + | + | + | – | + | – | – |

| Aeromonas veronii biovar veronii | + | + | + | + | + | + | – | + | + | – | – |

| Chromobacterium violaceumc | v | v | –d | – | v | – | + | – | + | – | ND |

ND, No data; V, variable; +, >90% of strains are positive; –, >90% of strains are negative.

aNutrient agar with 0% or 6% NaCl added.

bThiosulfate citrate bile salts sucrose agar.

c91% produce an insoluble violet pigment; often, nonpigmented strains are indole positive.

Comments Regarding Specific Organisms

The string test can be used to differentiate Vibrio spp. from Aeromonas spp. In this test, organisms are emulsified in 0.5% sodium deoxycholate, which lyses Vibrio cells, but not those of Aeromonas spp. Cell lysis releases DNA, which can be pulled up into a string with an inoculating loop (Figure 26-4).

Aeromonas spp. and C. violaceum can be identified using the characteristics shown in Table 26-5. Aeromonas spp. identified in clinical specimens should be identified as A. hydrophilia, A. caviae complex, or A. veronii complex.

Pigmented strains of C. violaceum are so distinctive that a presumptive identification can be made based on colonial appearance, oxidase, and Gram staining. Nonpigmented strains (approximately 9% of isolates) may be differentiated from Pseudomonas, Burkholderia, Brevundimonas, and Ralstonia organisms based on glucose fermentation and a positive test result for indole. Negative lysine and ornithine reactions are useful criteria for distinguishing C. violaceum from Plesiomonas shigelloides. In addition to the characteristics listed in Table 26-5, failure to ferment either maltose or mannitol also differentiates C. violaceum from Aeromonas spp.

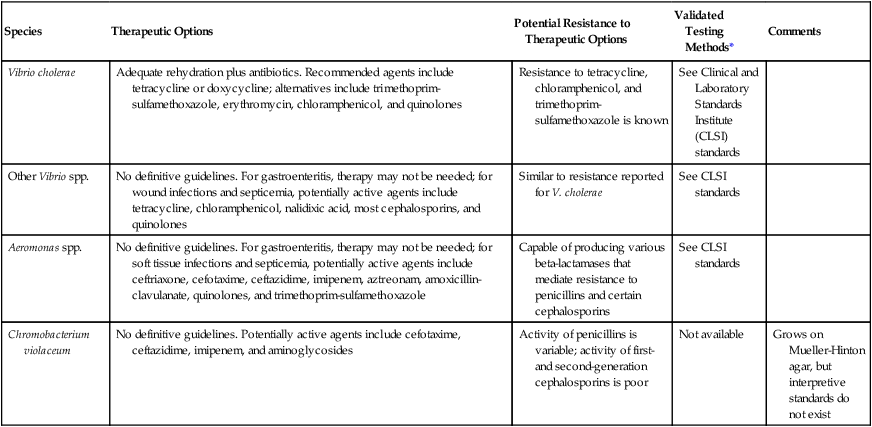

Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing and Therapy

Two components of the management of patients with cholera are rehydration and antimicrobial therapy (Table 26-6). Antimicrobials reduce the severity of the illness and shorten the duration of organism shedding. The drug of choice for cholera is tetracycline or doxycycline; however, resistance to these agents is known, and the use of other agents, such as chloramphenicol, ampicillin, or trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, may be necessary. The Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) has established methods for testing for V. cholerae, and the CLSI document should be consulted for this purpose.

TABLE 26-6

Antimicrobial Therapy and Susceptibility Testing

| Species | Therapeutic Options | Potential Resistance to Therapeutic Options | Validated Testing Methods* | Comments |

| Vibrio cholerae | Adequate rehydration plus antibiotics. Recommended agents include tetracycline or doxycycline; alternatives include trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, erythromycin, chloramphenicol, and quinolones | Resistance to tetracycline, chloramphenicol, and trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole is known | See Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) standards | |

| Other Vibrio spp. | No definitive guidelines. For gastroenteritis, therapy may not be needed; for wound infections and septicemia, potentially active agents include tetracycline, chloramphenicol, nalidixic acid, most cephalosporins, and quinolones | Similar to resistance reported for V. cholerae | See CLSI standards | |

| Aeromonas spp. | No definitive guidelines. For gastroenteritis, therapy may not be needed; for soft tissue infections and septicemia, potentially active agents include ceftriaxone, cefotaxime, ceftazidime, imipenem, aztreonam, amoxicillin-clavulanate, quinolones, and trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole | Capable of producing various beta-lactamases that mediate resistance to penicillins and certain cephalosporins | See CLSI standards | |

| Chromobacterium violaceum | No definitive guidelines. Potentially active agents include cefotaxime, ceftazidime, imipenem, and aminoglycosides | Activity of penicillins is variable; activity of first- and second-generation cephalosporins is poor | Not available | Grows on Mueller-Hinton agar, but interpretive standards do not exist |

*Validated testing methods include standard methods recommended by the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) and commercial methods approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA).

Antimicrobial agents with potential activity are listed, where appropriate, in Table 26-6. It is important to note these organisms’ ability to show resistance to therapeutic agents; especially noteworthy is the ability of Aeromonas spp. to produce various beta-lactamases.