Chapter 533 Vesicoureteral Reflux

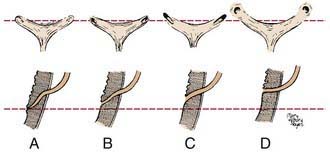

Vesicoureteral reflux refers to the retrograde flow of urine from the bladder to the ureter and kidney. The ureteral attachment to the bladder normally is oblique, between the bladder mucosa and detrusor muscle, creating a flap-valve mechanism that prevents reflux (Fig. 533-1). Reflux occurs when the submucosal tunnel between the mucosa and detrusor muscle is short or absent. Reflux usually is congenital, occurs in families, and affects approximately 1% of children.

Reflux predisposes to infection of the kidney (pyelonephritis) by facilitating the transport of bacteria from the bladder to the upper urinary tract (Chapter 532). The inflammatory reaction caused by a pyelonephritic infection can result in renal injury or scarring, also termed reflux-related renal injury or reflux nephropathy. In children with a febrile urinary tract infection (UTI), those with reflux are 3 times more likely to develop renal injury compared to those without reflux. Extensive renal scarring impairs renal function and can result in renin-mediated hypertension (Chapter 439), renal insufficiency or end-stage renal disease (Chapter 529), impaired somatic growth, and morbidity during pregnancy.

Classification

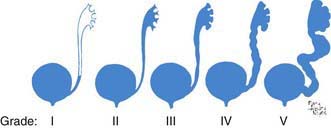

Reflux severity is graded using the International Reflux Study Classification of I to V and is based on the appearance of the urinary tract on a contrast voiding cystourethrogram (VCUG) (Figs. 533-2 and 533-3). The higher the reflux grade, the greater the likelihood of renal injury. Reflux severity is an indirect indication of the degree of abnormality of the ureterovesical junction.

Reflux may be primary or secondary (Table 533-1). Bladder and bowel dysfunction instability can worsen pre-existing reflux if there is a marginally competent ureterovesical junction. In the most severe cases, there is such massive reflux into the upper tracts that the bladder becomes overdistended. This condition, the megacystis-megaureter syndrome, occurs primarily in boys and may be unilateral or bilateral (Fig. 533-4). Reimplantation of the ureters into the bladder to correct reflux resolves the condition.

| TYPE | CAUSE |

|---|---|

| Primary | Congenital incompetence of the valvular mechanism of the vesicoureteral junction |

| Primary associated with other malformations of the ureterovesical junction |

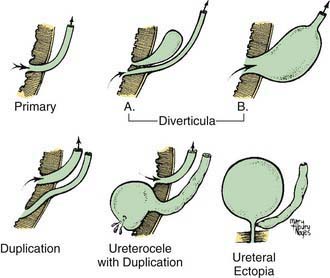

Approximately 1/125 children have a duplication of the upper urinary tract in which 2 ureters rather than 1 drain the kidney. Duplication may be partial or complete. In partial duplication, the ureters join above the bladder and there is 1 ureteral orifice. In complete duplication, the attachment of the lower pole ureter to the bladder is superior and lateral to the upper pole ureter. The valve-like mechanism for the lower pole ureter often is marginal, and reflux into the lower ureter occurs in as many as 50% of cases. Reflux occurs into both the lower and upper systems in some persons (Fig. 533-5). With a duplication anomaly, some patients have an ectopic ureter, in which the upper pole ureter drains outside the bladder (Chapters 534 and 537 and see Figs. 537-6 and 537-7). If the ectopic ureter drains into the bladder neck, typically it is obstructed and refluxes. Duplication anomalies also are common in children with a ureterocele, which is a cystic swelling of the intramural portion of the distal ureter. These patients often have reflux into the associated lower pole ureter or the contralateral ureter. Generally reflux is present when the ureter enters a bladder diverticulum (Fig. 533-6).

Figure 533-5 Various anatomic defects of the ureterovesical junction associated with vesicoureteral reflux.

Primary reflux occurs in association with several congenital urinary tract abnormalities. Of children with a multicystic dysplastic kidney or renal agenesis (Chapter 531), 15% have reflux into the contralateral kidney, and 10-15% of children with a ureteropelvic junction obstruction have reflux into either the hydronephrotic kidney or the contralateral kidney.

Clinical Manifestations

Reflux usually is discovered during evaluation for a UTI (Chapter 532). Among these children, 80% are female, and the average age at diagnosis is 2-3 yr. In other children, a VCUG is performed during evaluation of voiding dysfunction, renal insufficiency, hypertension, or other suspected pathologic process of the urinary tract. Primary reflux also may be discovered during evaluation for prenatal hydronephrosis. In this select population, 80% of affected children are male, and the reflux grade usually is higher than in girls whose reflux is diagnosed following a UTI.

Diagnosis

Diagnosis of reflux requires catheterization of the bladder, instillation of a solution containing iodinated contrast or a radiopharmaceutical, and radiologic imaging of the lower and upper urinary tract: a contrast VCUG or radionuclide cystogram (RNC), respectively. The bladder and upper urinary tracts are imaged during bladder filling and voiding. Reflux occurring during bladder filling is termed low-pressure or passive reflux; reflux during voiding is termed high-pressure or active reflux. Reflux in children with passive reflux is less likely to resolve spontaneously than in children who exhibit only active reflux. Radiation exposure during an RNC is significantly less than that from a contrast VCUG. The contrast study provides more anatomic information, such as demonstration of a duplex collecting system, ectopic ureter, paraureteral (bladder) diverticulum, bladder outlet obstruction in boys, upper urinary tract stasis, and signs of voiding dysfunction, such as a “spinning top” urethra in girls. The reflux grading system is based on the appearance on VCUG. Consequently, the VCUG is used as the initial study. For follow-up evaluation, the RNC often is preferred because of the lower radiation exposure (Fig. 533-7), although it may be difficult to determine whether the reflux severity has changed.

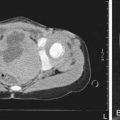

After reflux is diagnosed, assessment of the upper urinary tract is important. The goal of upper tract imaging is to assess whether renal scarring and associated urinary tract anomalies are present. Renal imaging typically is performed with a renal sonogram or renal scintigraphy (Fig. 533-8; Chapter 532).

The child should be evaluated for bladder and bowel dysfunction, including urgency, frequency, diurnal incontinence, infrequent voiding, or a combination of these (Chapter 537). Children with an overactive bladder often undergo a regimen of behavioral modification with timed voiding, and, on occasion, anticholinergic therapy.

Natural History

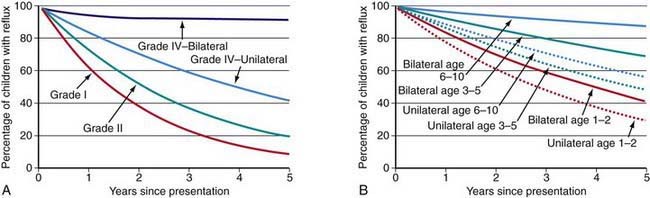

The incidence of renal scarring or reflux nephropathy increases with the grade of reflux. With bladder growth and maturation, the reflux grade can resolve or improve over time. Lower grades of reflux are much more likely to resolve than are higher grades. For grades I and II reflux, the likelihood of resolution is similar regardless of age at diagnosis and whether it is unilateral or bilateral. For grade III, a younger age at diagnosis and unilateral reflux usually are associated with a higher rate of spontaneous resolution (Fig. 533-9). Bilateral grade IV reflux is much less likely to resolve than is unilateral grade IV reflux. Grade V reflux rarely resolves. The mean age at reflux resolution is 6 yr.

Reflux does not usually cause renal injury in the absence of infection, but in situations with high-pressure reflux, as in children with posterior urethral valves, neuropathic bladder, and non-neurogenic neurogenic bladder (i.e., Hinman syndrome), sterile reflux can cause significant renal damage. Children with high-grade reflux who acquire a UTI are at significant risk for pyelonephritis and new renal scarring (see Fig. 533-8).

Treatment

Prophylaxis

Based on clinical series demonstrating the effectiveness of antibiotic prophylaxis, daily prophylaxis was recommended as initial therapy for most children with reflux. Drugs commonly used for prophylaxis include trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (TMP-SMX), trimethoprim, nitrofurantoin, or cephalexin, which are administered once daily at a dose of 25-30% of the dosage necessary to treat an acute infection. Prophylaxis was continued until reflux resolved or until the risk of reflux to the patient was considered to be low. Bladder and bowel dysfunction were aggressively treated (Chapter 537). A urine culture was recommended if there were symptoms or signs of a UTI. Children with renal scarring are at greatest risk for breakthrough febrile UTI. A VCUG or RNC and upper tract imaging were recommended every 12-18 mo. Annual assessment of the child’s height, weight, and blood pressure was recommended.

Surgery

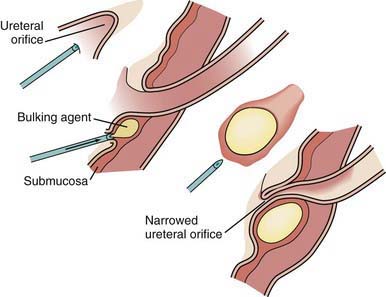

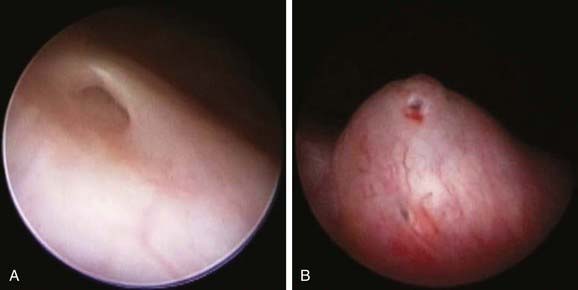

Endoscopic repair of reflux involves injection of a bulking agent through a cystoscope just beneath the ureteral orifice, creating an artificial flap-valve (Figs. 533-10 and 11). The advantage of subureteral injection is that it is a noninvasive outpatient procedure (performed under general anesthesia) with no recovery time. The success rate is 70-80% and is highest for lower grades of reflux. If the first injection is unsuccessful, one or two repeat injections can be performed. In October 2001, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved the use of a biodegradable material, dextran microspheres suspended in hyaluronic acid (Deflux), for subureteral injection. The reflux recurrence rate is approximately 10%. In the USA, currently >40% of antireflux surgery is performed with this procedure.

Brandstrom P, Esbjorner E, Herthelius M, et al. The Swedish Reflux Trial in Children: III. Urinary tract infection pattern. J Urol. 2010;184:288-291.

Brandstrom P, Neveus T, Sixt R, et al. The Swedish Reflux Trial in Children: IV. Renal damage. J Urol. 2010;184:292-297.

Cheng C-H, Tsai M-H, Huang Y-C, et al. Antibiotic resistance patterns of community-acquired urinary tract infections in children with vesicoureteral reflux receiving prophylactic antibiotic therapy. Pediatrics. 2008;122:1212-1217.

Cooper CS. Diagnosis and management of vesicoureteral reflux in children. Nat Rev Urol. 2009;6:481-489.

Coulthard MG. Is reflux nephropathy preventable, and will the NICE childhood UTI guidelines help? Arch Dis Child. 2008;93:196-199.

Craig JC, Simpson JM, Williams GJ, et al. Antibiotic prophylaxis and recurrent urinary tract infection in children. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:1748-1759.

Elder JS. Does antibiotic prophylaxis prevent renal scarring in children with vesicoureteral reflux? Nat Clin Prac Urol. 2008;5:646-647.

Elder JS. Therapy for vesicoureteral reflux: Antibiotic prophylaxis, urotherapy, open surgery, endoscopic injection, or observation? Curr Urol Rep. 2008;9:143-150.

Elder JS, Peters CA, Arant BSJr, et al. Pediatric Vesicoureteral Reflux Guidelines Panel summary report on the management of primary vesicoureteral reflux in children. J Urol. 1997;157:1846-1851.

Elder JS, Shah MB, Batiste LR, et al. Part 3: endoscopic injection versus antibiotic prophylaxis in the reduction of urinary tract infections in patients with vesicoureteral reflux. Curr Med Rep. 2007;23(Suppl 4):S15-S20.

Garin EH, Olavarria F, Garcia Nieto V, et al. Clinical significance of primary vesicoureteral reflux and urinary antibiotic prophylaxis after acute pyelonephritis: a multicenter, randomized, controlled study. Pediatrics. 2006;117:626-632.

Holmdahl G, Brandstrom P, Lackgren G, et al. The Swedish Reflux Trial in Children: II. Vesicoureteral reflux outcome. J Urol. 2010;184:280-285.

Keren R, Carpenter MAA, Hoberman A, et al. Rationale and design issues of the Randomized Intervention for Vesicoureteral Reflux (RIVUR) study. Pediatrics. 2008;122(Suppl 5):5240-5250.

Knudson MJ, Austin JC, McMillan ZM, et al. Predictive factors of early spontaneous resolution in children with primary vesicoureteral reflux. J Urol. 2007;178:1684-1688.

Leroy S, Vantalon S, Larakeb A, et al. Vesicoureteral reflux in children with urinary tract infection: comparison of diagnostic accuracy of renal US criteria. Radiology. 2010;255(3):890-898.

Nakamura M, Moriya K, Mitsui T, et al. Abnormal dimercaptosuccinic acid scan is a predictive factor of breakthrough urinary tract infection in children with primary vesicoureteral reflux. J Urol. 2009;182:1694-1697.

Novak TE, Mathews R, Martz K, et al. Progression of chronic kidney disease in children with vesicoureteral reflux: the North American Pediatric Renal Trials Collaborative Studies Database. J Urol. 2009;182:1678-1682.

Pennesi M, Travan L, Peratoner L, et al. Is antibiotic prophylaxis in children with vesicoureteral reflux effective in preventing pyelonephritis and renal scars? A randomized, controlled trial. Pediatrics. 2008;121:e1489-1494.

Peters CA, Skoog S, Elder JS, et al. Management and screening of primary vesicoureteral reflux in children: AUA guideline. (website) www.auanet.org/content/guidelines-and-quality-care/clinical-guidelines.cfm Accessed March 19, 2011

Roussey-Kesler G, Gadjos V, et al. Antibiotic prophylaxis for the prevention of recurrent urinary tract infection in children with low grade vesicoureteral reflux: results from a prospective randomized study. J Urol. 2008;179:674-679.

Routh JC, Inman BA, Reinburg Y. Dextranomer/hyaluronic acid for pediatric vesicoureteral reflux: systematic review. Pediatrics. 2010;125:1010-1019.

Sillen U, Brandstrom P, Jodal U, et al. The Swedish Reflux Trial in Children: V. Bladder dysfunction. J Urol. 2010;184:298-304.

Sjöström S, Sillén U, Jodal U, et al. Predictive factors for resolution of congenital high grade vesicoureteral reflux in infants: results of univariate and multivariate analyses. J Urol. 2010;183:1177-1184.

Wicher C, Hadley D, Ludlow D. 250 consecutive unilateral extravesical ureteral reimplantations in an outpatient setting. J Urol. 2010;184:311-314.