Chapter 36

Ventricular Tachycardia

1. What is the differential diagnosis of a wide complex tachycardia (WCT)?

The differential includes the following:

Ventricular tachycardia (VT) (monomorphic or polymorphic)

Ventricular tachycardia (VT) (monomorphic or polymorphic)

Supraventricular tachycardia (SVT) with aberrant conduction or underlying bundle branch block

Supraventricular tachycardia (SVT) with aberrant conduction or underlying bundle branch block

Antidromic SVT using an accessory pathway for antegrade conduction (Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome)

Antidromic SVT using an accessory pathway for antegrade conduction (Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome)

Toxicity related (hyperkalemia, digoxin, other drugs; Fig. 36-1)

Toxicity related (hyperkalemia, digoxin, other drugs; Fig. 36-1)

Figure 36-1 Bidirectional ventricular tachycardia in a patient with digitalis toxicity. (Modified from Marriott HJL, Conover MB: Advanced concepts in arrhythmias, ed 2, St Louis, 1989, Mosby.)

2. What is the pathophysiologic substrate of VT?

3. What is the most common underlying heart disease predisposing to VT?

4. Can VT occur in other nonischemic heart diseases?

Scar-related VT can occur in other nonischemic conditions whenever an inflammatory or infiltrative disorder damages the myocardium. Sarcoidosis or Chagas disease are typical examples in which VT can occur as a result of such nonischemic scars. Fatty infiltration of the right ventricle leads to areas of unexcitable myocardium that can generate reentrant circuits in patients with arrhythmogenic right ventricular dysplasia. Myocardial scars leading to reentry also occur after surgical correction of congenital heart diseases. Dilated cardiomyopathies can lead to reentry within the diseased conduction system, the so-called bundle-branch reentry, where impulses use the right and left bundles as antegrade and retrograde pathways (less commonly in the opposite direction). Conceivably, any structural heart disease can lead to reentry.

5. Can VT occur in the absence of structural heart disease?

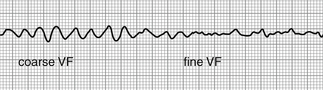

Primary electrical disorders can also lead to VT. Familial long QT syndromes typically lead to torsades des pointes, as does short QT syndrome. Brugada syndrome leads to primary ventricular fibrillation (Fig. 36-2). Catecholaminergic polymorphic ventricular tachycardia (CPVT) is the result of a mutation of the ryanodine receptor and typically causes exercise-induced bidirectional and polymorphic VT.

Figure 36-2 Coarse ventricular fibrillation (VF), which then degenerates further into fine ventricular fibrillation. (From Goldberger E: Treatment of cardiac emergencies, ed 5, St Louis, 1990, Mosby.)

6. What electrocardiogram (ECG) features favor VT as the cause of a wide complex tachycardia?

Presence of fusion beats, which identify simultaneous depolarization of the ventricle by both the normal conduction system and an ectopic impulse originating in the ventricle.

Presence of fusion beats, which identify simultaneous depolarization of the ventricle by both the normal conduction system and an ectopic impulse originating in the ventricle.

Capture beats, which are normally conducted sinus beats with a narrow QRS complex that generally occur at a shorter interval than the tachycardia.

Capture beats, which are normally conducted sinus beats with a narrow QRS complex that generally occur at a shorter interval than the tachycardia.

Atrioventricular (AV) dissociation, the finding of independent atrial and ventricular activity at differing rates (30% of cases). Look for visible P waves that “march through” (scan and compare ST segments and T waves, look for subtle QRS changes). If there are more QRSs than Ps, it is likely to be VT. If AV dissociation is not obvious, it can be unmasked with carotid sinus massage or administration of adenosine.

Atrioventricular (AV) dissociation, the finding of independent atrial and ventricular activity at differing rates (30% of cases). Look for visible P waves that “march through” (scan and compare ST segments and T waves, look for subtle QRS changes). If there are more QRSs than Ps, it is likely to be VT. If AV dissociation is not obvious, it can be unmasked with carotid sinus massage or administration of adenosine.

A QRS width more than 140 ms (RBBB morphology) or more than 160 ms (left bundle branch block [LBBB] morphology). These suggest VT, especially in the setting of a normal QRS during sinus rhythm.

A QRS width more than 140 ms (RBBB morphology) or more than 160 ms (left bundle branch block [LBBB] morphology). These suggest VT, especially in the setting of a normal QRS during sinus rhythm.

Limb lead concordance (identical QRS direction). If QRS is negative in I, II, and III (an extreme leftward or northwest axis), this strongly favors VT.

Limb lead concordance (identical QRS direction). If QRS is negative in I, II, and III (an extreme leftward or northwest axis), this strongly favors VT.

Precordial lead concordance (V1 through V6), especially negative concordance. This is highly specific for the diagnosis of VT.

Precordial lead concordance (V1 through V6), especially negative concordance. This is highly specific for the diagnosis of VT.

Certain QRS morphologic features also may be helpful. Most aberrant conduction patterns have a precordial rS complex, whereas the absence of rS complexes suggests VT. An atypical right bundle pattern (R > R′), a monophasic or biphasic QRS in lead V1, and a small R wave coupled with a large deep S wave or a Q-S complex in V6 support the diagnosis of VT.

Certain QRS morphologic features also may be helpful. Most aberrant conduction patterns have a precordial rS complex, whereas the absence of rS complexes suggests VT. An atypical right bundle pattern (R > R′), a monophasic or biphasic QRS in lead V1, and a small R wave coupled with a large deep S wave or a Q-S complex in V6 support the diagnosis of VT.

Presence of Q waves. Remember that postinfarction Q waves are preserved in VT. Their presence in WCT is a sign of previous infarction; therefore, VT is more likely.

Presence of Q waves. Remember that postinfarction Q waves are preserved in VT. Their presence in WCT is a sign of previous infarction; therefore, VT is more likely.

7. What is torsade de pointes?

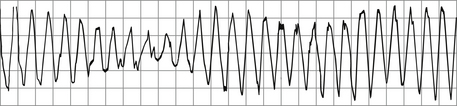

Torsade de pointes, or torsades, is a French term that literally means “twisting of the points.” It was first described by Dessertenne in 1966 and refers to a polymorphic intermediate ventricular rhythm between VT and ventricular fibrillation. It has a distinct morphology in which cycles of tachycardia with alternating peaks of QRS amplitude turn about the isoelectric line in a regular pattern (Fig. 36-3). Before the rhythm is triggered, a baseline prolonged QT interval and pathologic U waves are present, reflecting abnormal ventricular repolarization. A short-long-short sequence between the R-R interval (marked bradycardia or preceding pause) occurs before the trigger response. Drugs that prolong the QT (e.g., antiarrhythmics, some antibiotics and antifungals, and tricyclic antidepressants) and electrolyte disorders such as hypokalemia and hypomagnesemia are common triggers. When the ECG finding occurs, it should be treated as any life-threatening VT, and immediate efforts must be made to determine the underlying cause of QT lengthening.

Figure 36-3 Torsades de pointes, in which the QRS axis seems to rotate about the isoelectric point. (Modified from Olgin JE, Zipes DP: Specific arrhythmias: diagnosis and treatment. In Libby P, Bonow RO, Mann DL, Zipes DP, editors: Braunwald’s heart disease: a textbook of cardiovascular medicine, ed 8, Philadelphia, 2008, Saunders.)

8. What critical decisions must be made in the management of sustained VT?

9. What methods are used to terminate sustained VT?

With any question of hemodynamic instability, termination should be done immediately with synchronized direct current electrical cardioversion. Hemodynamic instability is defined as hypotension resulting in shock, congestive heart failure, myocardial ischemia (infarction or angina), or signs or symptoms of inadequate cerebral perfusion. It is important to ensure that the energy is delivered in a synchronized fashion before cardioversion. Failure to do so may accelerate the rhythm or induce ventricular fibrillation. If the patient is conscious, adequate intravenous (IV) sedation should always be provided. Termination of hemodynamically stable VT may be attempted medically. Reasonable drugs of choice are IV procainamide (or ajmaline in some European countries), lidocaine, and IV amiodarone. For ischemic monomorphic VT, intravenous lidocaine is also a reasonable option. Pace termination (either through transvenous insertion of a temporary pacer or by reprogramming an implantable cardioverter-defibrillator [ICD]) can be useful to treat patients with sustained monomorphic VT that is refractory to cardioversion or is recurrent despite the use of the above-mentioned drugs. If VT is associated with acute ischemia, urgent angiography and revascularization are paramount.

10. Once the acute episode is terminated, what are the next managing strategies?

This depends on the clinical situation and on the individual patient. Any potentially reversible cause—specifically, ischemia, heart failure, or electrolyte abnormalities—should be sought and treated aggressively. In general, beta-adrenergic blocking agents (β-blockers) are usually safe and effective and should be administered in most patients in whom concomitant antiarrhythmic drugs are indicated. Amiodarone and sotalol have been the mainstay of preventive therapy, especially in patients with left ventricle (LV) dysfunction. However, the long-term clinical success of medical regimens is low, and amiodarone carries a risk of serious side effects. All patients should be risk stratified for the likelihood of recurrence and subsequent risk of sudden cardiac death. Appropriate consultation with an electrophysiologist should be obtained to assess the need for ICD implantation (indications for ICDs are discussed in Chapter 38). Although cardiac device therapy has revolutionized treatment, providing excellent protection from sudden cardiac death, it does not prevent recurrences. Patients with defibrillators may remain symptomatic, with palpitations, syncope, and recurrent shocks for VT. Ablation of the reentrant circuits that cause VT also provides a nonpharmacologic option for the reduction of symptoms.

11. How is catheter ablation of VT performed?

Bibliography, Suggested Readings, and Websites

1. Brugada, P., Brugada, J., Mont, L., Smeets, J., Andries, E.W. A new approach to the differential diagnosis of a regular tachycardia with a wide QRS complex. Circulation. 1991;83:1649–1659.

2. Marchlinski, F.E., Callans, D.J., Gottlieb, C.D., Zado, E. Linear ablation lesions for control of unmappable ventricular tachycardia in patients with ischemic and nonischemic cardiomyopathy. Circulation. 2000;101:1288–1296.

3. Reddy, V.Y., Reynolds, M.R., Neuzil, P., et al. Prophylactic catheter ablation for the prevention of defibrillator therapy. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:2657–2665.

4. Zipes, D.P., Camm, A.J., Borggrefe, M., et al. ACC/AHA/ESC 2006 guidelines for management of patients with ventricular arrhythmias and the prevention of sudden cardiac death: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force and the European Society of Cardiology Committee for Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2006;114:e385–e484.