Chapter 39 Ventral and Ventrolateral Subaxial Decompression

General Considerations

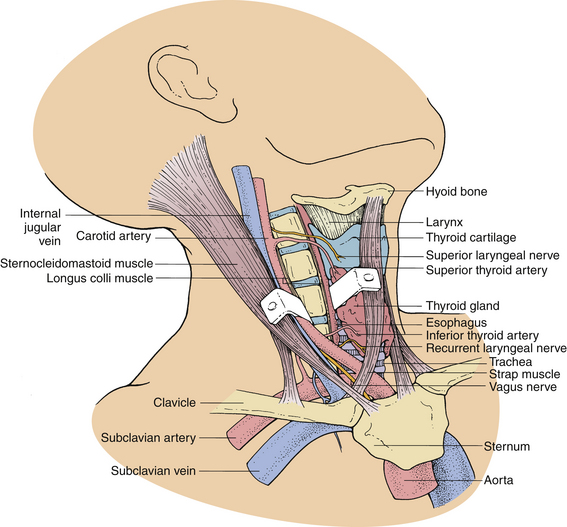

The ventral approach to the cervical spine is performed through a plane between the sternocleidomastoid muscle and the carotid sheath laterally and the strap muscles and tracheoesophageal viscera medially. This approach is appropriate for ventral cervical discectomy, vertebrectomy, fusion, and instrumentation (Fig. 39-1).

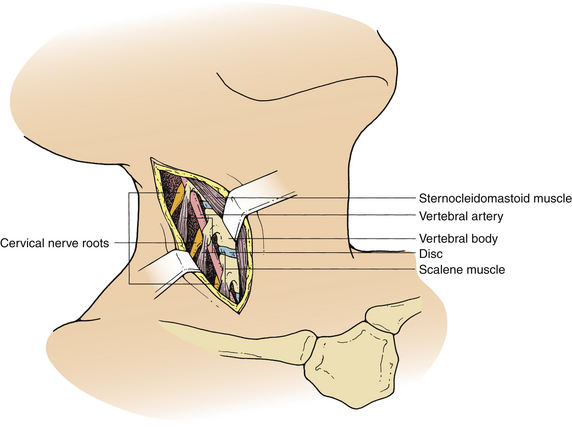

The ventrolateral approach, however, is more suitable for decompression of the vertebral artery in the transverse foramen or between the foramina or spinal nerve roots outside the spinal canal. Two different techniques are described in the literature. Verbiest’s1 technique is performed through the same plane as the ventral approach. However, further exposure is performed lateral to the longus colli muscle on the ipsilateral side. This exposure allows visualization of the costotransverse lamella, which forms the roof of the foramen transversarium covering the vertebral artery. Hodgson,2 on the other hand, approached the cervical spine lateral to the sternocleidomastoid muscle and the carotid sheath. These structures, along with the musculovisceral column, are retracted medially (Fig. 39-2). The remainder of the exposure is similar to that described by Verbiest, with the exception that the longus colli muscles are retracted medially to laterally to gain access to the vertebral artery.

Specific Complications, Avoidance, and Management

Preoperative Period

Intraoperative evoked potential monitoring can be used to identify and avoid dangerous manipulation of the neural tissue during surgery.3 However, there is currently no convincing evidence that the use of this modality improves outcome after decompressive surgery. Somatosensory evoked potentials (SSEP) are most commonly used for this purpose. However, this type of monitoring may be associated with false-positive intraoperative SSEP changes, thus creating significant anxiety for the surgeon and possibly unnecessary anesthetic and surgical maneuvers. Motor evoked potential monitoring reflects the function of the ventral spinal cord tracts more reliably than does SSEP monitoring and may avoid some of the false-positive intraoperative changes observed with SSEP.

Intraoperative Period

The risk is probably balanced by the convenience of the position for right-handed surgeons. A left-sided approach, on the other hand, carries the risk of injury to the thoracic duct during exposure of the lower cervical spine. A recent review of 328 patients who underwent ventral cervical spine fusion procedures showed no association between the side of the approach and the incidence of RLN symptoms.4

Injury to the Esophagus and Pharynx

Dysphagia is a common problem after ventral cervical surgery and is usually secondary to edema from retraction. This symptom usually resolves within a few days without any treatment. In certain cases, however, it may persist as long as several weeks; rarely, it may be permanent. It is more common in elderly patients and in those who had extensive mobilization of the upper esophagus or hypopharynx. In a questionnaire mailed to 497 patients who had undergone ventral cervical fusion procedures, 60% reported some dysphagia after the surgical procedure compared to 23% in the control group.5

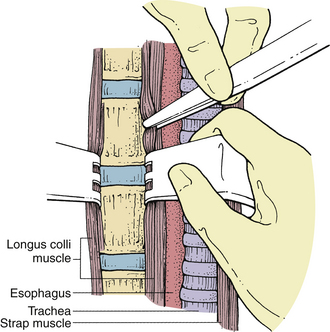

Esophageal or pharyngeal lacerations can occur, especially in the upper cervical region where the hypopharynx is thinner, either from sharp dissection or from the teeth of self-retaining retractors. If esophageal perforation is recognized intraoperatively, it should be repaired primarily. The wound should be drained and the patient placed on nasogastric drainage for at least 7 to 10 days. Fusion in these circumstances is contraindicated. Subsequently, a swallow study with a water-soluble contrast agent should be obtained to confirm that the perforation has sealed. In the majority of cases, the injury to the esophagus is not recognized during surgery and shows symptoms later as a local infection, fistula, sepsis, or mediastinitis.6,7 The presence of crepitus or an enlarging mass in the neck or mediastinal air on a chest radiograph usually suggests the strong possibility of an esophageal perforation. Diagnosis can be confirmed with an esophagogram. However, this test may not always be positive when esophageal injury is present. Esophagoscopy or a postesophagogram CT scan may also demonstrate a perforation. Treatment of a delayed perforation consists of nasogastric drainage, antibiotics, and reexploration of the incision. If a defect is found, it should be repaired and a wound drain placed.6 To avoid this complication, the longus colli muscles should be freed enough rostrally, caudally, and laterally so that the sharp teeth of the self-retaining retractors can be placed safely under them without risk of dislodgement during the procedure (Fig. 39-3). In addition, the esophagus and other soft tissue structures should be hidden by the retractors to avoid injury by the high-speed drill during bone removal.

FIGURE 39-3 Placement of self-retaining retractors under the longus colli muscle to prevent dislodgement during surgery.

Occasionally, perforation of the esophagus can result from a displaced graft.8 To avoid this problem, some surgeons recommend reapproximation of the longus colli muscles over the graft. When a displaced graft perforates the esophagus, reexploration is required. Either replacement or removal of the graft may be indicated, depending on the need for the graft to maintain stability. The esophageal perforation should be repaired, if possible, and the patient treated with antibiotics and nasogastric drainage.

Injury to the Laryngeal Nerves

The superior laryngeal nerve is a branch of the inferior ganglion of the vagus nerve and innervates the cricothyroid muscle. The superior thyroid artery, encountered above C4, is an important anatomic landmark for the superior laryngeal nerve. Damage to this nerve may result in hoarseness, but it often produces symptoms such as easy voice fatigue.9 To avoid injury to this nerve, one should be aware of its anatomic location.

On the left side, the inferior (recurrent) laryngeal nerve loops under the arch of the aorta and is protected in the left tracheoesophageal groove. On the right side, however, the RLN travels around the subclavian artery, passing dorsomedially to the side of the trachea and esophagus. It is vulnerable as it passes from the subclavian artery to the right tracheoesophageal groove. The inferior thyroid artery on the right side is an anatomic marker for the RLN. The nerve usually enters the tracheoesophageal groove, the point at which the inferior thyroid artery enters the lower pole of the thyroid. Damage to the RLN may result in hoarseness, vocal breathiness or fatigue, weak cough, dysphagia, or aspiration.10

Preoperative insertion of a nasogastric tube not only allows easier identification of the esophagus for protection against an esophageal injury, but also allows localization of the tracheoesophageal groove and the avoidance of the plane. Endotracheal tube-related RLN injury has also been cited. Monitoring of the endotracheal cuff pressure and its release after retractor placement decreased the rate of RLN temporary paralysis from 6.4% to 1.7% in one series.11

One should also be aware of the anatomic variations, especially on the right side, where the RLN may be nonrecurrent. However, the frequency of this aberration is well below 1%.12 In this situation, the RLN travels directly from the vagus nerve and the carotid sheath to the larynx. If a suspected nonrecurrent nerve is encountered, it may be identified with a nerve stimulator and laryngoscopic examination of the vocal cords. If it cannot be retracted safely, it is best to abandon the procedure and use a left-sided approach.

The true incidence of RLN injury is difficult to determine but is probably about 1% to 2%.4,13 Beutler et al.4 reported that the incidence of RLN symptoms was 2.1% with anterior cervical discectomy, 3.5% with corpectomy, 3% with instrumentation, and 9.5% with reoperative anterior surgery.

Because many patients have some degree of voice change after ventral cervical operations, a thorough investigation is not required in most cases. However, a laryngoscopic examination should be performed in persistent cases. If RLN palsy is present, the vocal cord will be faced in the paramedian position. Immediate treatment is not usually required for a paralyzed vocal cord because, in most instances, the nerve has not been severed, and the condition will resolve with time.13 In some patients, hoarseness or voice dysfunction may be minimal, not requiring treatment. However, patients with persistent hoarseness after several months can be treated with injections of hemostatic gelatin (Gelfoam) or Teflon into the vocal cord. Gelfoam produces a temporary improvement and may be used as an interim measure pending spontaneous return of function. Teflon injection is a permanent treatment modality that is used in patients in whom no recovery is expected.

Injury to the Structures in the Carotid Sheath

It is important to recognize that manipulation of the carotid artery may result in a stroke secondary to either mechanical compression of the artery or dislodgement of debris from a preexisting carotid plaque.14 In some cases, it may be useful to monitor the temporal artery pulse after placement of the self-retaining retractors to avoid the risk of stroke as a result of carotid occlusion from retraction.

Injury to the Vertebral Artery

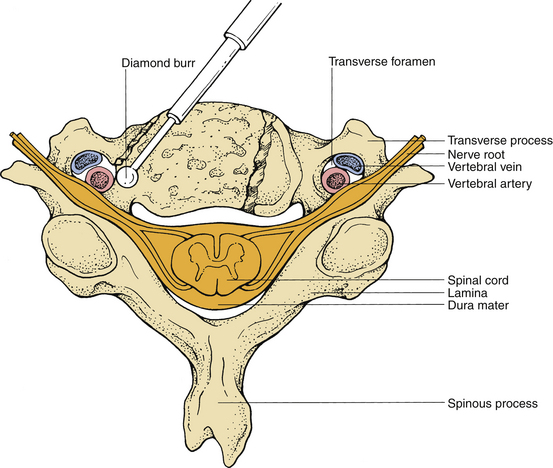

Injury to the vertebral artery may result from asymmetrical and far lateral bone removal and is most likely to occur on the left side during a standard right-sided approach (Fig. 39-4). In a cadaveric study, the course of the vertebral artery was analyzed in 222 cervical spines. A 2.7% incidence of tortuous vertebral artery was identified.15 Injury to the vertebral artery can also result from aggressive dissection of the longus colli muscles, which injures the vascular structures between the transverse processes.16 Although primary repair of the vertebral arteries has been recommended, this is usually very difficult. Commonly, bleeding can be controlled with gentle compression using a muscle pledget, Gelfoam, or oxidized cellulose (Surgicel), after which an angiogram should be obtained to rule out the development of an arteriovenous fistula or pseudoaneurysm.17 To avoid this injury, one should identify the midline carefully and proceed with drilling accordingly.

Occasionally, transection of the vertebral artery can occur inadvertently during decompression of the vertebral artery via a ventrolateral approach. When this occurs, it requires control of the bleeding by a ligature at the level above and below the lesion. The risk of neurologic deficit after a unilateral vertebral artery occlusion is low.16 Thorough mobilization of the vertebral artery invariably causes bleeding from the surrounding venous plexus; consequently, vigorous retraction and aggressive mobilization of the vertebral artery should be avoided to minimize hemorrhage.

Injury to the Sympathetic Chain

The sympathetic chain may be more vulnerable to damage during ventral lower cervical spine procedures because it is situated closer to the medial border of the longus colli muscles at C6 than at C3. The longus colli muscles diverge laterally and the sympathetic chain converges medially at C6.18 Injury to the cervical sympathetic chain, which results in Horner syndrome, is unusual but can result from either retraction or transection of the sympathetic chain. The incidence of permanent injury is less than 1%.19 To avoid this injury during a ventral approach, the soft tissue dissection should be limited to the medial aspect of the longus colli muscles.

Increased Neurologic Deficit

Increased neurologic deficit after a ventral cervical operation is unusual. Most spinal cord or nerve root injuries are associated with technical mishaps (excepting most C5 deficits). Although the exact figure is difficult to determine, Flynn19 reported a 1.3% incidence of additional radicular dysfunction and a 3.3% incidence of worsening myelopathy.

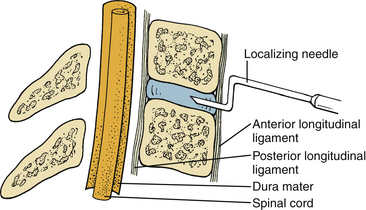

To avoid neurologic injury, certain measures should be undertaken at every step of the procedure. Important precautionary measures regarding positioning, neck hyperextension, intubation, and electrophysiologic monitoring have been described. During intraoperative localization, the localizing needle (18-gauge spinal needle) in the disc space should be bent at the tip, as shown in Figure 39-5, so that inadvertent advancement of the needle into the spinal canal is impossible.

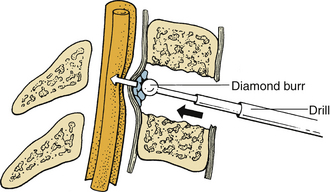

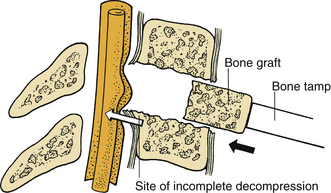

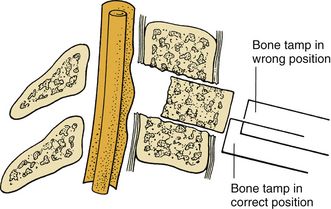

During the removal of spondylotic ridges, it is important that osteophytes not be disconnected from the vertebral bodies until they have been thinned sufficiently to permit removal with fine curettes. Otherwise, further attempts to drill may result in compression of the spinal cord (Fig. 39-6). Achieving a complete decompression before placement of the bone graft is also crucial. As shown in Figure 39-7, in instances of incomplete decompression, tapping of the bone graft may result in compression of the spinal cord. During the final advancement of the bone graft, a bone tamp should be positioned in such a way that one half of the surface of the tamp is placed against the remaining rostral or caudal vertebral body (Fig. 39-8). This placement avoids an inadvertent advancement of the graft into the spinal canal and thereby prevents spinal cord compression. Countersinking of the bone graft can be accomplished by angling the tamp but maintaining the position of the tamp relative to the vertebral body (see Fig. 39-8). Occasionally, misplacement or displacement of a bone graft may cause nerve or cord compression. To avoid this injury, the depth of the graft should be measured carefully, and the depth of the vertebral body should be measured on preoperative imaging studies. If the depth of the bone graft in an anteroposterior plane is limited to 13 mm, penetration of the spinal canal is unlikely. Nerve root injuries are less common than spinal cord injuries, but for unclear reasons, the C5 nerve root is very sensitive to trauma.20

Sleep-induced apnea has been reported as an unusual complication of ventral cervical spine surgery. It is usually a self-limited process. Supportive respiratory therapy is occasionally needed.21

Postoperative Period

Postoperative Infection

Infectious processes can occur after a ventral cervical operation and can affect only the superficial layers or can involve the deeper structures. These are reported in 0.4% to 2% of patients with spine complications.22 Superficial infections external to the platysma muscle can be treated by simple opening of the incision, followed by dressing changes and administration of appropriate antibiotics and secondary closure.

Epidural abscesses and meningitis have also been reported in association with ventral cervical operations. However, these complications are quite rare.23 If a patient has progressive postoperative spinal cord dysfunction, with or without evidence of osteomyelitis or systemic signs of sepsis, epidural abscess should always be considered in the differential diagnosis. Either MRI or CT myelography should be used to establish the diagnosis. Meningitis should be considered in a septic patient if a dural laceration was observed or suspected intraoperatively. Lumbar puncture is required to confirm the suspicion.

Graft-Related Complications

The predominant complications related to the bone graft are graft collapse, extrusion and migration, and nonunion. These may occur from suboptimal sizing, vertebral endplate fracture, postoperative trauma, or inadequate immobilization. Graft collapse is most frequently observed in elderly patients with osteoporotic bone. If there is any question regarding the structural integrity of autologous bone, an allograft should be used. However, in younger patients, autologous graft is stronger than allograft in resisting axial compression. The majority of patients with graft collapse are asymptomatic and do not require reoperation.

Graft extrusion and migration are reported in 2.1% to 4.6% of single-level fusions and in 10% to 29% of multilevel fusions with bony or ligamentous instability after ventral cervical discectomy and fusion. Graft displacement may require reoperation if the patient reports dysphagia, respiratory compromise, or neurologic deficits.24,25A well-fitting graft and placement under compression may help reduce this complication.

Graft pseudarthrosis has been reported in 5% to 10% of patients who undergo single-level fusion, in 15% to 20% of two-level fusions, and in 30% to 63% of three-level fusions.24 Despite radiographic nonunion, the majority of these patients are clinically asymptomatic, and reoperation is not indicated. However, persistent neck pain, progressive angulation, and subluxation mandate graft revision.

Ardon H., Van Calenbergh F., Van Raemdonck D., et al. Oesophageal perforation after anterior cervical surgery: management in four patients. Acta Neurochir (Wien). 2009;151:297-302.

Bose B., Sestokas A.K., Schwartz D.M. Neurophysiological detection of iatrogenic C-5 nerve deficit during anterior cervical spinal surgery. J Neurosurg Spine. 2007;6:381-385.

Ebraheim N.A., Lu J., Yang H., et al. Vulnerability of the sympathetic trunk during the anterior approach to the lower cervical spine. Spine. 2000;25:1603-1606.

Eskander M.S., Connolly P.J., Eskander J.P., Brooks D.D. Injury of an aberrant vertebral artery during a routine corpectomy: a case report and literature review. Spinal Cord. 2009;47:773-775.

Kahraman S., Sirin S., Erdogan E., et al. Is dysphonia permanent or temporary after anterior cervical approach? Eur Spine J. 2007;16:2092-2095.

Miscusi M., Bellitti A., Peschillo S., et al. Does recurrent laryngeal nerve anatomy condition the choice of the side for approaching the anterior cervical spine? J Neurosurg Sci. 2007;51:61-64.

1. Verbiest H. A lateral approach to the cervical spine: technique and indications. J Neurosurg. 1968;28:191-203.

2. Hodgson A. Approach to the cervical spine C3-C7. Clin Orthop. 1965;39:129-134.

3. Khan M.H., Smith P.N., Balzer J.R., et al. Intraoperative somatosensory evoked potential monitoring during cervical spine corpectomy surgery: experience with 508 cases. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2006;31:E105-E113.

4. Beutler W.J., Sweeney C.A., Connolly P.J. Recurrent laryngeal nerve injury with anterior cervical spine surgery risk with laterality of surgical approach. Spine. 2001;26:1337-1342.

5. Winslow C.P., Winslow T.J., Wax M.K. Dysphonia and dysphagia following the anterior approach to the cervical spine. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2001;127:51-55.

6. Ardon H., Van Calenbergh F., Van Raemdonck D., et al. Oesophageal perforation after anterior cervical surgery: management in four patients. Acta Neurochir (Wien). 2009;151:297-302.

7. Dakwar E., Uribe J.S., Padhya T.A., Vale F.L. Management of delayed esophageal perforations after anterior cervical spinal surgery. J Neurosurg Spine. 2009;11:320-325.

8. Shenoy S.N., Raja A. Delayed pharyngo-esophageal perforation: rare complication of anterior cervical spine surgery. Neurol India. 2003;51:534-536.

9. Melamed H., Harris M.B., Awasthi D. Anatomic considerations of superior laryngeal nerve during anterior cervical spine procedures. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2002;27:E83-E86.

10. Miscusi M., Bellitti A., Peschillo S., et al. Does recurrent laryngeal nerve anatomy condition the choice of the side for approaching the anterior cervical spine? J Neurosurg Sci. 2007;51:61-64.

11. Apfelbaum R.I., Kriskovich M.D., Haller J.R. On the incidence, cause, and prevention of recurrent laryngeal nerve palsies during anterior cervical spine surgery. Spine. 2000;25:2906-2912.

12. Cannon R.C. The anomaly of nonrecurrent laryngeal nerve: identification and management. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1999;120:769-771.

13. Kahraman S., Sirin S., Erdogan E., et al. Is dysphonia permanent or temporary after anterior cervical approach? Eur Spine J. 2007;16:2092-2095.

14. Yeh Y.C., Sun W.Z., Lin C.P., et al. Prolonged retraction on the normal common carotid artery induced lethal stroke after cervical spine surgery. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2004;29:E431-E434.

15. Curylo L.J., Mason H.C., Bohlman H.H., Yoo J.U. Tortuous course of the vertebral artery and anterior cervical decompression: a cadaveric and clinical case study. Spine. 2000;25:2860-2864.

16. Burke J.P., Gerszten P.C., Welch W.C. Iatrogenic vertebral artery injury during anterior cervical spine surgery. Spine J. 2005;5:508-514.

17. Eskander M.S., Connolly P.J., Eskander J.P., Brooks D.D. Injury of an aberrant vertebral artery during a routine corpectomy: a case report and literature review. Spinal Cord. 2009;47:773-775.

18. Ebraheim N.A., Lu J., Yang H., et al. Vulnerability of the sympathetic trunk during the anterior approach to the lower cervical spine. Spine. 2000;25:1603-1606.

19. Flynn T.B. Neurologic complications of anterior cervical interbody fusion. Spine. 1982;7:536-539.

20. Bose B., Sestokas A.K., Schwartz D.M. Neurophysiological detection of iatrogenic C-5 nerve deficit during anterior cervical spinal surgery. J Neurosurg Spine. 2007;6:381-385.

21. Krieger A.J., Rosomoff H.L. Sleep-induced apnea. 2. Respiratory failure after anterior spinal surgery. J Neurosurg. 1974;40:181-185.

22. Salcman M. Complications of cervical spine surgery. Crit Care Med. 2001;29:2027-2028.

23. Bertalanffy H., Eggert H.R. Complications of anterior cervical discectomy without fusion in 450 consecutive patients. Acta Neurochir (Wien). 1989;99:41-50.

24. Parsons I.M., Kang J.D. Mechanisms of failure after anterior cervical disc surgery. Curr Opin Orthop. 1998;9:2-11.

25. Zaveri G.R., Ford M. Cervical spondylosis: the role of anterior instrumentation after decompression and fusion. J Spinal Disord. 2001;14:10-16.