Chapter 19 Venous Malformations

While these lesions can have mass effect on adjacent structures, they are not tumors. A clearly organized classification system was presented by Mullikan, Glowacki, and colleagues in 1992, and this classification system was adopted in 1996 by the International Society for the Study of Vascular Anomalies (ISSVA). The classification system clearly separates tumors (e.g., hemangioma) from the vascular spaces that characterize a vascular malformation.1

What are Hemangiomas?

Hemangiomas are childhood masses characterized histologically by high endothelial cell turnover and are characterized by cell markers (GLUT-1, merosin, Lewis Y) that are otherwise found only in human placental tissue and that display phasicity characterized by a rapid proliferative phase, plateau phase, and slow involutional phase. The proper nomenclature for these lesions is infantile hemangioma. Infantile hemangiomas are benign vascular tumors that are not usually present at the time of birth but instead become evident within the first 2 to 3 weeks of life. They are the most common benign tumor of infancy. There is a subgroup of hemangiomas that present fully formed at birth known as congenital hemangiomas. These congenital hemangiomas (as opposed to infantile hemangiomas) do not exhibit the expected accelerated postnatal growth. Some congenital hemangiomas involute rapidly over the first year of life and are called rapidly involuting congenital hemangiomas (RICHs), while some may persist indefinitely without treatment and are called noninvoluting congenital hemangiomas (NICHs).1

The majority of infantile hemangiomas are localized and, although disconcerting to parents and care providers, are nonthreatenting.2 For these lesions, observation and routine monitoring by the pediatrician or dermatologist are acceptable treatment options. A minority of infantile hemangiomas can, however, cause significant morbidity. These require early recognition, timely referral to a specialist, and prompt intervention to minimize complications. Worrisome presentations include multiple hemangiomas and sensitive locations such as beard distribution, periocular, perioral, nasal tip, large regions of the face and neck, and the lumbosacral spine region. In general, larger hemangiomas located on the face are more likely to require treatment. One of the strongest indications for the use of the laser is the presence of ulceration. Other symptoms necessitating therapeutic intervention include congestive heart failure, airway obstruction, dysphagia, infection, failure to thrive, external auditory canal occlusion, visual axis impairment, and severe facial deformity.

Vascular Malformations

Low-Flow Vascular Malformations—Venous Malformations

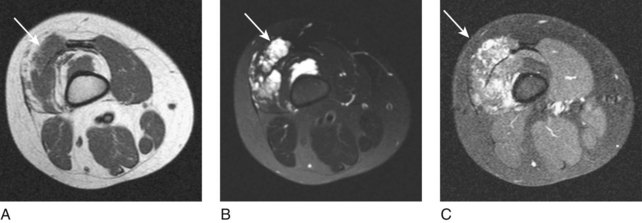

Low-flow venous malformations are the most common form of vascular malformation—simplified, they are a number of tortuous vascular channels. They will be evident at birth and will grow with the child. These are common birthmarks present at birth, although they can be clinically occult if deep in location and usually do not become symptomatic until late childhood/early adolescence. Deep subcutaneous or intramuscular venous malformations often manifest with only local swelling and pain. The diagnosis can be difficult because extremity varicosities may be the only visible sign, especially in deep venous malformations. Superficial venous malformations can be seen with bluish-purple skin discoloration. Venous malformations can be divided into truncal and extratruncal lesions. On physical examination, these lesions are soft and easily compressible and will often demonstrate engorgement, especially when the affected extremity is placed in a dependent position. Extratruncal lesions occur from remnants of primitive vessels early in development and are usually dysplastic and diffusely infiltrative. They commonly involve the deep soft tissue structures but patients may have constant pain. Truncal venous malformations occur in differentiated and later-stage vascular structures and patients may have an impressive cutaneous manifestation with limb swelling and varicosities. Diffuse malformations involve multiple areas or regions and are usually part of a syndrome such as Klippel-Trenaunay syndrome. Diagnosis of a venous malformations can usually be made by clinical examination; however, imaging studies such as magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) are performed to evaluate the extent and guide treatment. On MRI, venous malformations are T1 isointense to muscle and T2 hyperintense and demonstrate late enhancement (Fig. 19-1).

Treatment of Venous Malformations

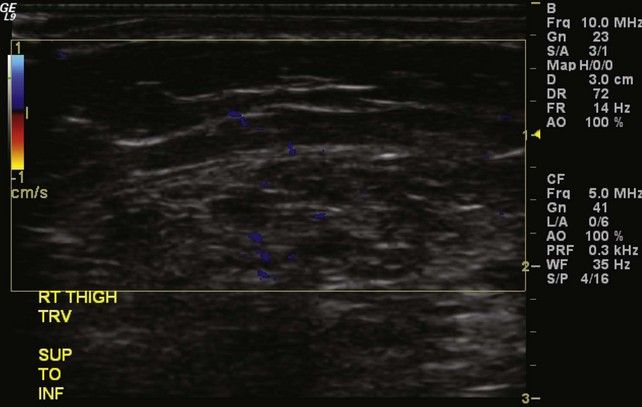

Preprocedure evaluation of a malformation with either ultrasound or MRI is helpful not only in defining the extent of the abnormality but also in aiding to determine possible direct access into the lesion (Figs. 19-2 and 19-3). Access into the malformation is usually performed with ultrasound and fluoroscopic guidance (Fig. 19-4). Biplane fluoroscopy can be used if the location of the lesion allows. Direct comparison with the MR images can also be very helpful. Proper positioning on the angiographic table is critical to successfully access the malformation and to allow proper anesthesia monitoring. All alcohol embolization procedures are performed with the patient under general anesthesia to allow for proper sedation and pain management as well as to prepare should complications of treatment (such as cardiovascular collapse) occur. Additionally, a tourniquet for control with a calibrated cuff can be used if the location of the lesions allows. When using a tourniquet, we do not exceed diastolic blood pressure and often only use minimal pressures in the 20 to 40 mm Hg range.

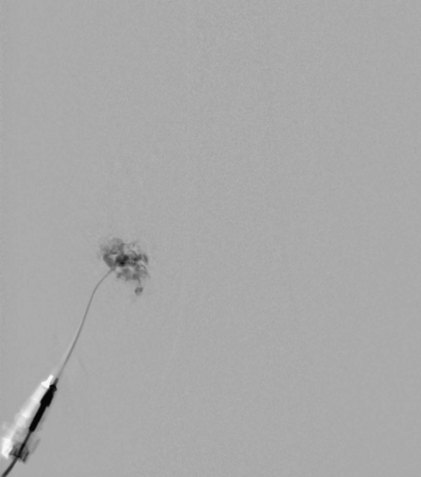

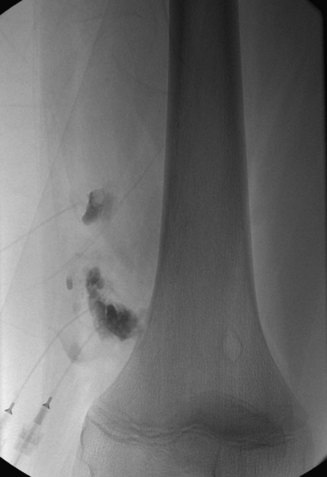

The technique for the alcohol administration has evolved over the past 10 years. Previously, dehydrated ethanol was opacified with a small amount of ethiodized oil (Ethiodol) to increase the visualization of the administered alcohol under fluoroscopic control. Currently, we use a negative contrast technique. This consists of opacification of the malformation with contrast followed by administration of the ethyl alcohol that replaces the contrast on live fluoroscopic evaluation (Fig. 19-5). Once we have either treated the entire lesion or reached our sclerosant limits, the procedure is concluded (Fig. 19-6). The absolute maximum for ethyl alcohol is 1 mL/kg. In our practice, we rarely exceed 0.5 mL/kg in one procedure. A good working dose limit for ethyl alcohol is 0.25 mg/kg for the entire case. We also limit our total injected volume to 0.1 mL/kg/injection and allow at least 5 minutes between alcohol administrations. By adhering to these recommendations, we have completed safe treatment for many patients without the use of pulmonary arterial catheter monitoring.

1 Mulliken JB, Young AE. Vascular birthmarks: hemangiomas and malformations. Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 1988.

2 Bittles MA, Sidhu MK, Sze RW, et al. Multidetector CT angiography of pediatric vascular malformations and hemangiomas: utility of 3-D reformatting in differential diagnosis. Pediatr Radiol. 2005;35:1100-1106.

Al-Adnani M, Williams S, Rampling D, et al. Histopathological reporting of paediatric cutaneous vascular anomalies in relation to proposed multidisciplinary classification system. J Clin Pathol. 2006;59:1278-1282.

Bauman NM, Burke DK, Smith RJ. Treatment of massive or life-threatening hemangiomas with recombinant alpha (2a)-interferon. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1997;117:99-110.

Cho SK, Do YS, Kim DI, et al. Peripheral arteriovenous malformations with a dominant outflow vein: results of ethanol embolization. Korean J Radiol. 2008;9:258-267.

Rosenblatt M. Endovascular management of venous malformations. Phlebology. 2007;22:264-275.

van der Linden E, Pattynama PMT, Heeres BC, et al. Long-term patient satisfaction after percutaneous treatment of peripheral vascular malformations. Radiology. 2009;251:926-932.

van Rijswijk CSP, van der Linden E, van der Woude H-J, et al. Value of dynamic contrast-enhanced MR imaging in diagnosing and classifying peripheral vascular malformations. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2002;178:1181-1187.