Venous disorders of the lower limb

Venous thrombosis and the post-thrombotic limb

Anatomy of the lower limb venous system

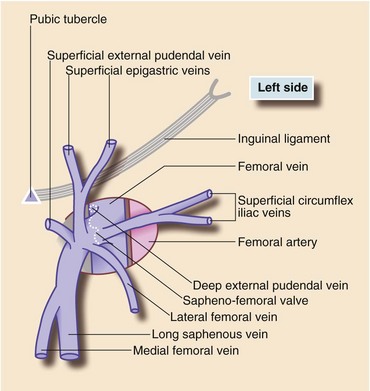

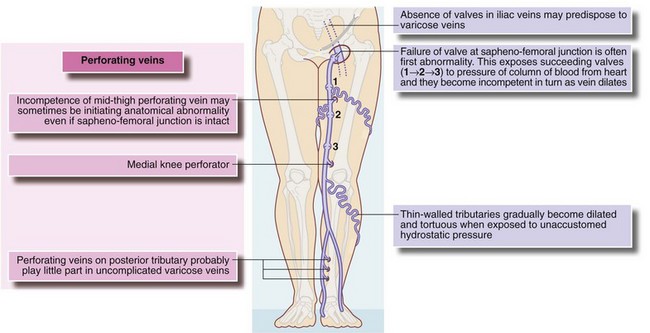

The skin and other tissues superficial to the deep fascia drain into the superficial system with two main vessels, the long (great) saphenous vein and the short (small) saphenous vein. The long saphenous vein receives tributaries from the antero-medial aspect of the limb (and lower anterior abdominal wall), and penetrates the fascia lata in the groin to drain into the (deep) femoral vein (Figs 43.3). The short saphenous vein drains the posterior part of the leg and passes through the deep fascia into the popliteal vein of the deep venous system. There is a network of interconnecting superficial veins that drain blood from the limb if long or short saphenous veins are removed or ablated. The superficial system has no muscle pump to aid venous return but the valves normally prevent retrograde flow, particularly at sapheno-femoral and sapheno-popliteal junctions. Several perforating veins drain superficial blood into the deep system; valves on these normally ensure one-way flow. Most perforators lie medially on the calf above the ankle but there is a fairly constant ‘Hunterian perforator’ in the medial mid-thigh.

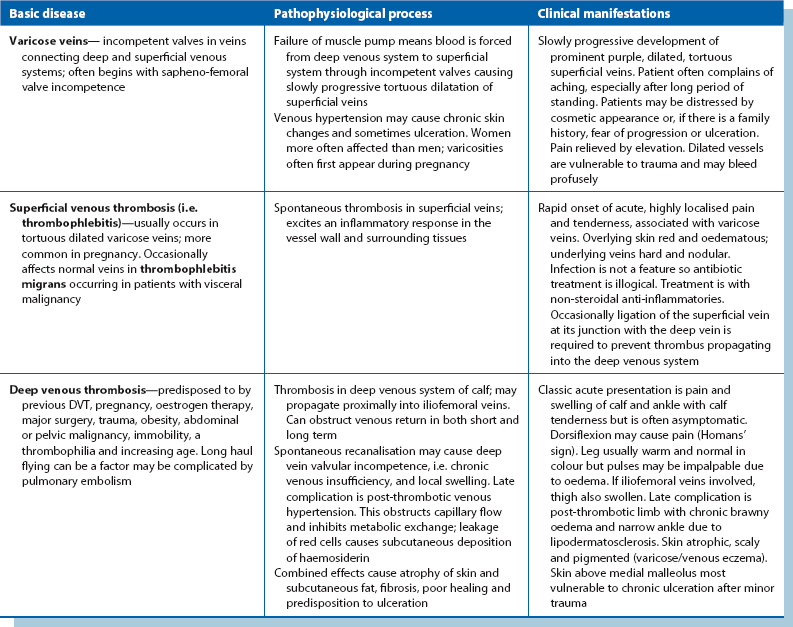

Presentation and consequences of venous thrombosis (Table 43.1)

Thromboembolic disease and its consequences are common and include acute deep vein thrombosis (DVT), pulmonary embolism and superficial thrombophlebitis (‘phlebitis’). Deep venous thrombosis most commonly occurs as a complication of major surgery, lower limb fractures, myocardial infarction or other severe illness. About one-third of DVTs present with no apparent cause, though many of these patients have a detectable prothrombotic state. The risk factors, clinical presentations and management of acute DVT and pulmonary embolism are discussed in Chapter 12, p. 167.

Pathophysiology of post-thrombotic problems

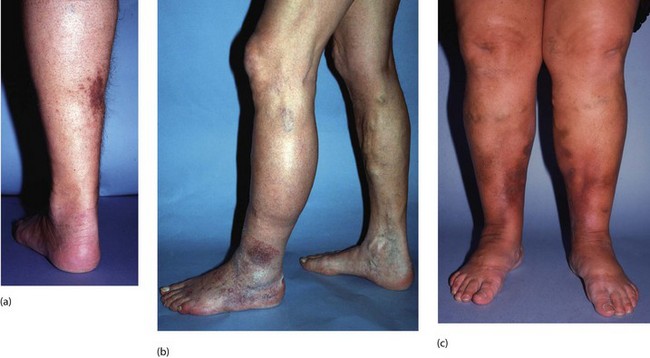

In the normal adult limb, ankle venous pressure while standing is about 125 cm of water. This falls markedly during walking as a result of the calf pump and valve function. In the post-thrombotic limb, where blood refluxes or veins remain occluded, ankle venous pressure remains high during walking. This leads secondarily to valve incompetence in perforating veins. Blood is forced into the superficial system causing local venous hypertension, disrupting normal vascular dynamics in skin and subcutaneous tissues. This may impair skin vitality and healing ability. Characteristic local signs of a gross post-thrombotic limb are listed in Box 43.1 (see also Fig. 43.1).

The following factors contribute to the clinical features:

• Venous stagnation restricts arterial replenishment of capillary blood

• Arteriovenous shunts beneath the affected skin divert blood away from dermal capillaries

• Venous hypertension causes dilatation of local venules and the capillary network, allowing plasma proteins to leak into the interstitial spaces. Fibrin polymerises forming pericapillary cuffs which may interfere with metabolic exchange between blood and tissues

Investigation of venous insufficiency

The diagnostic pathway depends on responses to the following questions:

• Is the condition venous in origin? This is suggested by a history of DVT, prolonged bed rest in the past or lower limb fractures, or a finding of varicose veins or a ‘champagne-bottle’ leg (i.e. proximal limb swelling due to oedema and distal narrowing due to fat atrophy and fibrosis). If the condition is not venous, another cause of ulceration and swelling should be sought

• If it is venous, is there superficial (Fig. 43.2) or deep venous insufficiency, or a combination of both?

• If a combination, how much is due to superficial venous insufficiency and therefore likely to respond to surgery (unlike deep venous reflux)

Patients should undergo a colour-flow duplex Doppler ultrasound investigation, now the ‘gold standard’. This can give detailed information on the presence and severity of reflux in deep and superficial veins as well as determining whether there is venous obstruction. Functional detail will also be gleaned about the superficial system to enable targeted and appropriate treatment.

Management of post-thrombotic problems

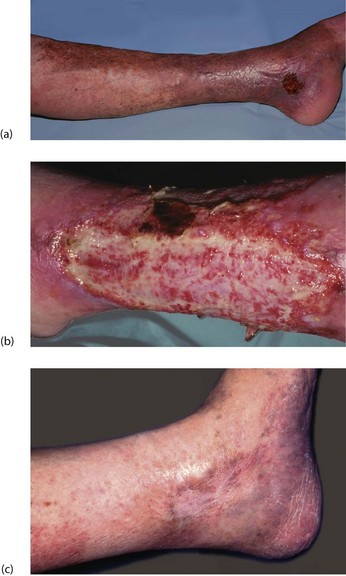

Venous ulcers: Ulcers may develop spontaneously but are more commonly initiated by minor trauma which fails to heal, often complicated by secondary infection. Most venous ulcers can be healed by non-operative methods provided treatment is applied skilfully. Even if operative treatment is needed, conservative measures are used to prepare the limb. These include reducing swelling by multi-layer bandaging, removing necrotic tissue from the ulcer base and controlling cellulitis.

The systolic arterial pressure in the leg should be measured relative to the upper limb (i.e. ankle brachial pressure index (ABPI)—see Ch. 41, p. 497). If the ABPI is < 0.8, the arterial circulation may be inadequate; it should be assessed and necessary treatment instigated before compression therapy as (a) poor arterial supply may be part of the reason for non-healing of an ulcer and (b) compression bandaging with low arterial pressure will make ulceration worse.

Long-term care and prevention: As soon as a post-thrombotic limb is recognised, the patient should use graduated compression stockings and take care to avoid even minor trauma, especially to the gaiter area above the medial malleolus. Flaking and dryness of the skin should be treated with a moisturiser.

Varicose veins

Varicose veins are dilated, tortuous and prominent superficial veins in the lower limb (see Fig. 43.5). Varicose veins are common worldwide, being present in about 20% of people aged 20, increasing to 80% at 60 years. Nevertheless, only about 12% have symptoms or develop complications.

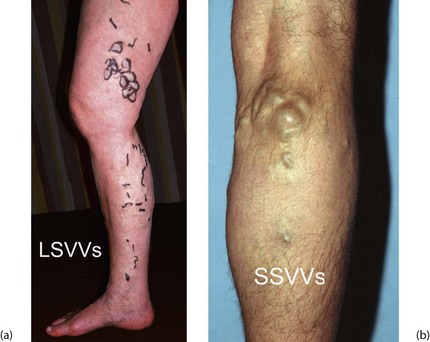

Fig. 43.5 Varicose veins

(a) Typical varicosities in the long saphenous territory (LSVVs) evident both above and below knee and most prominent on the medial side of the limb. The indelible black markings were made immediately prior to surgery by the operating surgeon with the patient standing. (b) Typical short saphenous varicosities (SSVVs), which do not extend above the knee. These veins could not be controlled with an above-knee tourniquet and there was gross reflux evident on hand-held Doppler examination, confirmed on colour duplex Doppler scanning. The sapheno-popliteal junction (SPJ) has a variable position and should be marked before surgery using ultrasound so the surgeon knows where to site the incision

Pathophysiology of varicose veins

Abnormal communication between deep and superficial venous systems is crucial in the development of varicose veins. The process probably begins with failure of the valve at the sapheno-femoral junction, leading to an uninterrupted column of blood from the heart which progressively dilates superficial veins down the limb (see Fig. 43.5a). Varicose veins usually develop slowly over 10–20 years, so surgical treatment is rarely urgent. The long saphenous system is involved in about 90% and the short saphenous in 25% (some have both systems involved).

Hereditary factors appear to play a part in some patients, especially in men and in those who develop varicosities in their teens. Predisposing anatomical factors may include congenital absence of valves in iliac veins or abnormal vein wall elasticity. DVT plays little part in causing varicose veins. Rarely, multiple congenital arteriovenous fistulae (Klippel–Trenaunay and other syndromes) cause gross varicose veins. In these patients, there is gigantism of the lower limb and often venous ulceration (see Ch. 46). A technique of examining varicose veins is shown in Figure 43.6.

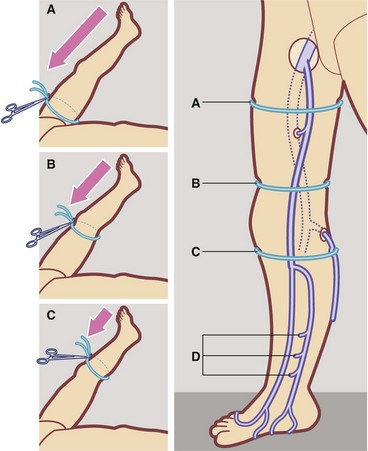

Fig. 43.6 A technique of examining varicose veins

Elevate limb and ensure veins are emptied by massaging distal to proximal. Apply tourniquet tightly around upper thigh A then stand patient up. Does tourniquet prevent veins filling and removing it cause rapid filling from above? If so, main communication is at the sapheno-femoral junction. If veins fill rapidly with tourniquet in place, repeat the test with tourniquet above the knee B. If this controls filling, then main communication is mid-thigh perforator. If this tourniquet fails to control filling, repeat below knee C. If this controls filling, communication is likely to be short saphenous-popliteal or medial knee perforator incompetence. If no tourniquet controls filling, communication is probably by one or more distal perforating veins, often post-thrombotic in origin D. Note that 80% of varicose veins involve the long saphenous system, sometimes with short saphenous incompetence as well.

Symptoms and signs of varicose veins

Investigation of varicose veins

Traditional investigation of varicose veins includes clinical examination and tourniquet techniques (Fig. 43.6). As a screening investigation in clinic, hand-held ultrasound Doppler allows assessment of reflux at sapheno-femoral (SFJ) and sapheno-popliteal junctions (SPJ) and within the long and short saphenous veins. The probe is placed over either junction, the calf is pressed and the examiner can hear if there is significant reflux outwards through the junction on release of calf pressure. Formal duplex scanning is now advocated for all cases where intervention is planned. This gives accurate assessment of superficial and deep systems, determining anatomical areas of reflux and allowing appraisal for endovenous therapy.

Management of varicose veins

Indications for surgical treatment of varicose veins

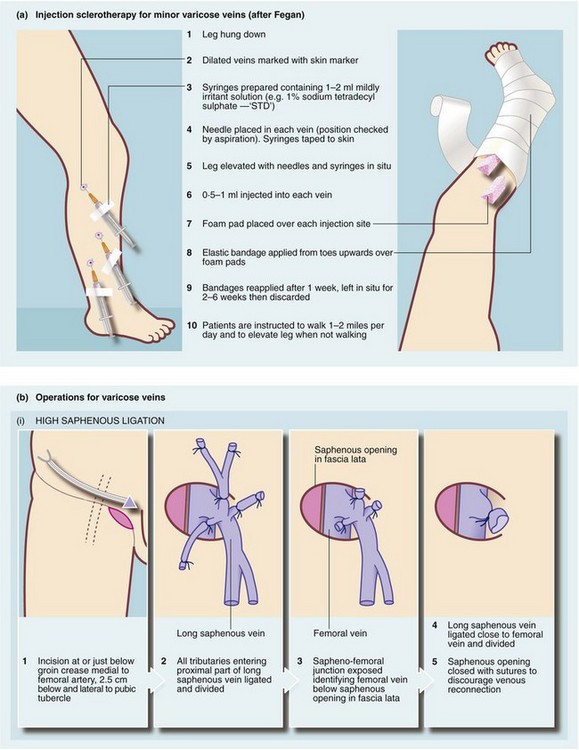

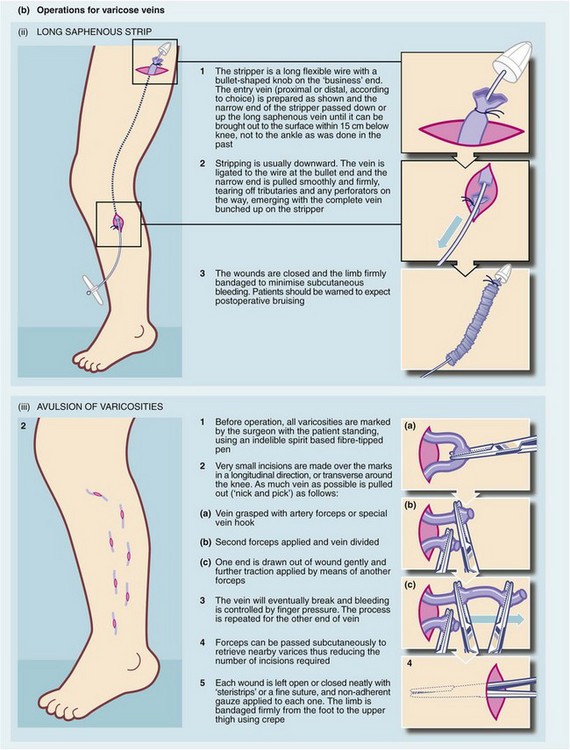

Injection sclerotherapy (e.g. Fegan’s technique) is used for treating small cosmetically unattractive varicose veins below the knee but is unsuitable for major varicosities, particularly in the thigh. This type of injection sclerotherapy and surgery for varicose veins is shown in Figure 43.7.