Veins and lymphatics

MANAGING LEG SUPERFICIAL VENOUS DISEASE (VARICOSE VEIN SURGERY)

Appraise

‘Varicose veins’ of the leg are classified according to their size:

1. Trunk (true) varicose veins are large tortuous dilated protruding superficial veins. They result from superficial venous incompetence due to valvular damage.

2. Reticular veins are small (2–3 mm), protrude and do not blanch on pressure.

3. Thread or spider veins are small (<1mm) intradermal subcutaneous veins, which blanch on pressure. Both reticular and thread veins result from alterations in the subcutaneous collagen, probably with local venous incompetence.

Venous complications where varicose vein surgery may help include:

1. bleeding from varicose veins, which may occur as a result of trauma from sports, such as rugby, or at the delicate ankle skin secondary to venous hypertension

2. superficial thrombophlebitis which can be secondary to minor trauma to varicose veins as well as other causes such as malignancy. When the thrombus extends to near the saphenofemoral or popliteal junction urgent intervention is indicated to prevent progression. If not, intervention should be considered once the acute phlebitis has settled.

3. Ankle venous hypertensive skin changes. These include frank ulceration as well as lipodermatosclerotic skin thickening with haemosiderin pigmentation; the term does not apply to the age-related development of thread veins at the ankle. Treating any superficial venous incompetence will reduce the risk of ulcer recurrence, although it does not improve the rate of ulcer healing.

Varicose veins symptoms where surgery may help include:

1. Aching: Varicose veins produce a deep dull heavy aching fullness in the legs, which comes on when standing and is eased by elevating the leg or wearing support stockings. Any other leg discomfort is probably not due to venous disease, and venous treatment will not improve the discomfort.

2. Throbbing: The varicose veins can throb, and some patients refer to a sensation similar to water trickling down the leg.

3. Itching: The enlarged veins can itch, especially in warm conditions. This is worsened when eczematous skin changes develop.

4. Night cramps: These can be associated with varicose veins, although there are several other causes and intervention is not usually considered if this is the sole symptom.

5. Cosmesis: In Western society, especially amongst women, it is common to expose the legs.

6. Ankle oedema: This can also be associated with varicose veins, although there are many other causes and treatment solely for this symptom should generally be avoided.

1. The symptoms match the signs and therefore the indications for treatment (as outlined above).

2. The veins are primary and not secondary and associated with a vascular malformation or more complex aetiology. Hints that the varicose veins may not be simple and primary include a history of leg fracture; repeated DVTs; venous or leg complications from abdominal surgery and pregnancy; abnormally placed varicose veins (such as laterally along the leg, vulval, or abdominal wall varices); erythematous leg birth marks, leg or foot size discrepancy.

Use of the hand held Doppler in the clinic adds little.

Venous flow: An occluded vein suggests the presence of thrombosis.

Venous flow: An occluded vein suggests the presence of thrombosis.

Valve competency: Two-directional Doppler flow on calf compression and release indicates incompetence.

Valve competency: Two-directional Doppler flow on calf compression and release indicates incompetence.

Vein wall compliance: A patent vein that is difficult to compress on direct pressure suggests wall scarring, as occurs following phlebitis or a DVT.

Vein wall compliance: A patent vein that is difficult to compress on direct pressure suggests wall scarring, as occurs following phlebitis or a DVT.

In complex cases the Duplex ultrasound scan will help define the venous anatomy and distinguish between low and high flow arteriovenous malformations.

In complex cases the Duplex ultrasound scan will help define the venous anatomy and distinguish between low and high flow arteriovenous malformations.

3. Magnetic resonance venography (MRV)

Reserved for treating (not investigating) complex malformations and pelvic varices.

There are three surgical steps to superficial venous disease intervention:

1. Dislocation of the superficial venous system from the deep venous system

Preparation

1. Carefully re-examine patients admitted for varicose vein surgery. Confirm or exclude incompetence in the long and short saphenous veins and in the calf perforating veins.

2. Skin mark with an arrow the origin of the saphenous vein incompetence in the groin or popliteal fossa.

3. With the patient standing, mark all prominent varicosities with indelible pen as ‘tram-lines’ on either side of the vein to avoid ‘tattooing’ through the incision.

4. Preoperative marking with Duplex scanning is useful for locating the termination of the short saphenous vein and the sites of incompetent perforating veins.

5. Consent the patient for the planned procedure, warning of the risks of recurrent varicose veins, bleeding, wound infection, scarring and numbness from cutaneous nerve neuropraxia. With recurrent varicose veins warn of the risk of worsening ankle oedema.

6. Ensure that the equipment, including the ultrasound machine, is available and working.

HIGH SAPHENOUS VEIN LIGATION (TRENDELENBURG’S OPERATION) AND STRIPPING OF LONG SAPHENOUS VEIN

Prepare

1. Have the skin of the groin and leg shaved before the operation.

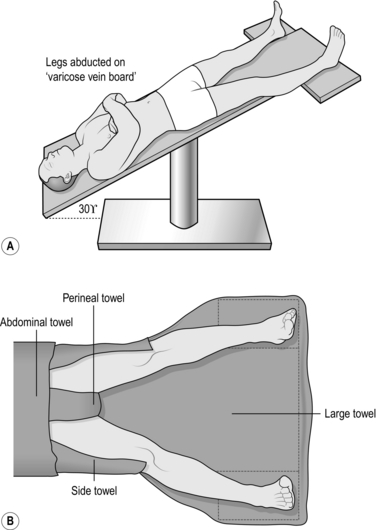

2. Place the patient supine in the Trendelenburg position with approximately 30° of head-down tilt, both legs abducted by 20° from the midline and the ankles lying on a padded board. This allows easy access and reduces intra-operative haemorrhage (Fig. 24.1).

3. Prepare all exposed surfaces of the limb from the foot to the groin and up to the level of the umbilicus with aqueous 0.5% chlorhexidine acetate solution, while an assistant elevates the leg by lifting the patient’s foot.

Access

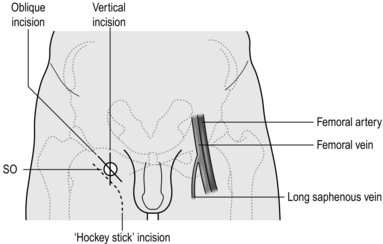

1. Make an oblique incision just below and parallel to the inguinal ligament in the groin crease, over the saphenofemoral junction, which is lateral to the femoral pulse and medial to the adductor tendon/pubic tubercle (Fig. 24.2).

2. Deepen the incision through the subcutaneous fat, which is spread by digital retraction, divide Scarpa’s fascia and hold it apart by the insertion of a self-retaining retractor such as West’s. Modify the length of incision depending on the build of the patient.

Action

1. Dissect the long saphenous vein out of the surrounding fat. Pass a controlling large tie around the vein and trace it upwards and towards the saphenofemoral junction. The perivenous plane is simple to open and is bloodless when entered.

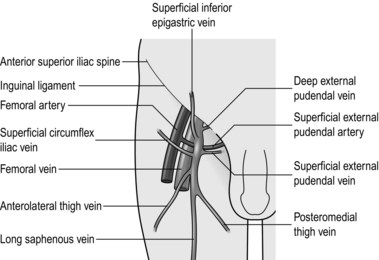

2. Dissect out all tributaries that join the long saphenous vein near its termination, ligating them with 3/0 absorbable suture before dividing them. The superficial inferior epigastric vein, the superficial circumflex iliac vein, and the superficial and deep external pudendal veins all join the saphenous trunk near its termination. In addition, the posteromedial and anterolateral thigh veins terminate close to the saphenofemoral junction (Fig. 24.3). One or more of these veins may join together before emptying into the saphenous trunk.

3. After these tributaries have been divided, approach the saphenofemoral junction. The long saphenous vein dips down through the cribriform fascia over the foramen ovale to join the femoral vein. The femoral vein tends to be a lighter colour. Carefully separate the subcutaneous fat from the vein by blunt dissection to follow its path. Display the femoral vein for approximately 1 cm above the saphenofemoral junction, and clear any small tributaries entering from either side. Dissecting the femoral vein downwards risks damaging the superficial external pudendal artery, which may pass either anterior or posterior to the saphenous vein. If damaged, ligate and divide it with impunity.

4. Ligate the long saphenous vein in continuity with 2/0 absorbable suture, flush with the saphenofemoral junction, and divide it. For greater safety doubly ligate or transfix the saphenous stump. Alternatively, oversew the termination with a 3/0 polypropylene continuous suture.

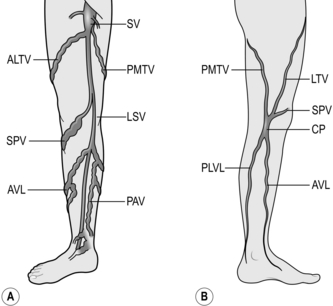

5. Place a strong ligature around the divided distal end of the long saphenous trunk and hold it up to occlude retrograde blood flow, then make a small transverse venotomy below the ligature and introduce a disposable plastic stripper with a blunt tip into the saphenous vein. Gently manipulate the tip of the stripper downwards until it is a hand’s breadth below the knee, where it may remain in the saphenous vein or pass into a tributary (Fig. 24.4). If it will not pass, withdraw the stripper and re-insert it with a rotational action. Tie the ligature at the top end to prevent blood from leaking out of the divided long saphenous trunk.

6. Make a short oblique incision in one of the skin crease tension lines, 1 cm in length, over the palpable tip of the stripper. Ensure that the incision is large enough to allow the head of the stripper to pass. Palpate the vein containing the stripper and dissect it off the saphenous nerve.

7. Make a small side-hole in the vein through which the tip of the stripper can be delivered. Tie the proximal end of the stripper to the long saphenous vein with a strong, long length of suture.

8. Strip the long saphenous vein from the groin to the knee with steady downward traction (invert strip). Ease the stripper and the bunched up vein through the lower incision. Clamp the attached long saphenous vein and any tributaries, divide and ligate it with 2/0 polyglactin.

9. Prevent excessive bleeding from the stripper track by gently rolling a swab along the course of the vein before applying bandages. Some surgeons apply a sterile tourniquet to the leg to prevent excessive haemorrhage.

Postoperative

1. Keep the leg elevated 15° above the horizontal in bed.

2. Encourage early mobilization after applying additional compression bandages over the bandages put on in the theatre. This reduces haematoma formation and provides better support when the patient stands. Thromboembolism prophylaxis stockings do not provide sufficient compression.

3. Advise the patient to walk rather than stand still or sit with the feet down.

4. Discharge fit patients on the day of surgery with advice on compression stockings, exercise and adequate hydration postoperatively.

SAPHENOPOPLITEAL LIGATION AND STRIPPING

Appraise

1. This is indicated if there is gross dilatation and reflux in the short saphenous trunk or its tributaries.

2. The location of the saphenopopliteal junction is very variable and, in a third of cases, the short saphenous vein enters the popliteal vein above or below the middle of the popliteal fossa.

3. Preoperative Duplex scanning and marking of the saphenopopliteal junction provide accurate information about the termination of the short saphenous vein and its proximal tributaries.

4. Carry out short saphenous vein ligation first if you intend to strip the long saphenous vein under the same anaesthetic.

Prepare

1. Place the patient prone, with pillows under the chest, midriff and pelvis. This demands careful supervision from the anaesthetist to ensure that ventilation is maintained and the patient is safely placed on the operating table with adequate pressure area support.

2. If under general anaesthetic, place the operating table in 30° of head-down tilt and slightly abduct the legs to ease access.

Action

1. Find the short saphenous vein in the popliteal fossa and dissect it from the surrounding fat and accompanying sural nerve, which is usually laterally placed.

2. Follow the short saphenous vein cranially as it dips down to the popliteal vein. Dissecting onto the popliteal vein can be difficult and risks damaging neighbouring structures. It is therefore wise to ligate the saphenous vein with an absorbable 2/0 suture as it dips down, and not at the popliteal vein junction. Ligate the saphenous vein more caudally and divide between the ligatures. Doubly ligate the stump of the short saphenous vein with 2/0 absorbable sutures.

3. In 2.5–10% of patients there is a tributary joining the short saphenous vein from above, known as the vein of Giacomini; carefully divide it between ligatures.

4. Stripping the short saphenous vein is not always undertaken:

If it is, place a strong ligature around the divided end of the short saphenous trunk and hold it up to occlude retrograde blood flow, make a small transverse venotomy and introduce a disposable plastic stripper into the saphenous vein.

If it is, place a strong ligature around the divided end of the short saphenous trunk and hold it up to occlude retrograde blood flow, make a small transverse venotomy and introduce a disposable plastic stripper into the saphenous vein.

Gently manipulate the tip of the stripper downwards until it is a hand’s breadth above the lateral maleolus. Make a 1-cm vertical incision in a skin crease tension lines over the palpable stripper tip. Dissect the sural nerve off the vein containing the stripper. Deliver the stripper through the vein.

Gently manipulate the tip of the stripper downwards until it is a hand’s breadth above the lateral maleolus. Make a 1-cm vertical incision in a skin crease tension lines over the palpable stripper tip. Dissect the sural nerve off the vein containing the stripper. Deliver the stripper through the vein.

Tie the proximal end of the stripper to the short saphenous vein with a strong, long length of suture and strip the saphenous vein with steady downward traction.

Tie the proximal end of the stripper to the short saphenous vein with a strong, long length of suture and strip the saphenous vein with steady downward traction.

Ease the stripper and the bunched up vein through the lower incision.

Ease the stripper and the bunched up vein through the lower incision.

Clamp the attached saphenous vein and any tributaries, divide and ligate it with 2/0 polyglactin.

Clamp the attached saphenous vein and any tributaries, divide and ligate it with 2/0 polyglactin.

Complications

1. These are similar to those of long saphenous vein surgery but with an additional risk of damage to the popliteal artery, vein and nerve during popliteal dissection. This is particularly likely if there has been previous knee surgery, such as a total knee replacement, as the anatomy may be distorted.

2. The sural nerve is easily damaged unless you gently dissect it free from the vein at the ankle. For this reason, some surgeons never strip the short saphenous vein. There is no controlled trial to settle this controversy and the subject remains a matter of opinion.

ENDOVENOUS THERMAL ABLATION OF THE LONG SAPHENOUS VEIN

Appraise

1. Endoluminal radiofrequency ablation (VNUS closure system) and endovascular laser treatment have been introduced as minimally invasive alternatives to ligation and stripping of the saphenofemoral or saphenopopliteal veins.

2. Both techniques aim to thermally damage the vessel intima, causing fibrosis and ultimately obliteration of the long saphenous vein trunk.

3. Under ultrasound guidance a catheter is percutaneously passed up the long saphenous vein from just below the knee to within 2 cm of the saphenofemoral junction. To dissipate heat produced by the laser or radio waves, local anaesthetic and saline solution is infiltrated around the long saphenous vein. The heated catheter is slowly withdrawn, closing the vein behind it.

4. The procedure needs to be undertaken under aseptic conditions, but is often performed in a treatment room rather than main operating theatre, especially if under local anaesthetic.

Prepare

1. Be happy with the layout of the theatre, in particular the positioning of the ultrasound machine and radiofrequency/laser equipment. Often it is easiest to sit on the side opposite the leg being treated, facing the machinery, which is on the same side as the affected leg. It is helpful to have the scrub nurse and trays on the same side as you at the foot end, ready to help feed guide-wires.

2. Check all equipment is available, working and compliant. Ensure the staff understand the procedure.

3. With the patient supine in a negative Trendelenburg position with approximately 30° of head-up tilt, prepare all exposed surfaces of the limb from the foot to the groin and up to the level of the umbilicus with aqueous 0.5% chlorhexidine acetate solution, while an assistant elevates the leg by lifting the patient’s foot.

Action

1. The long saphenous vein is cannulated at the level of the knee. The ultrasound probe (Linear 38 mm Transducer) is placed in a sterile sleeve with sterile ultrasound jelly on the leg (use lots of it). At a depth of less than 4 cm the long saphenous vein is identified as a black hole in transverse section. The patency and size of the vein along its length from the saphenofemoral junction to below the knee is confirmed.

2. A one-part hollow needle is then inserted into the vein under ultrasound guidance. Initially attempt to cannulate the vein distally towards the foot, because if this fails and the vein goes into spasm, a more proximal part of the vein can still be used. Before attempting a second pass, flush the needle with normal saline. You will know you are in the vein because blood flows freely from the needle.

3. Pass the guide-wire through the needle up into the saphenous vein. Occasionally, veins are small and a hydrophilic guide-wire is needed.

4. Confirm the guide-wire is in the vein by seeing the white dot in the black hole of the vein on ultrasound.

5. Pass the sheath over the guide-wire into the vein. Occasionally, a small nick in the skin is necessary to get the sheath through. Once the sheath introducer is removed, check there is good back-bleeding and flush the sheath.

6. Next insert the radiofrequency/laser catheter up the vein to within 2 cm of the saphenofemoral junction. This is ensured by measuring the distance on the patient and the catheter (in some cases the catheter has a light on its tip which can be seen through the skin) and by ultrasound identification of junction and catheter tip.

7. To dissipate the heat produced by the radiofrequency/laser catheter tip, local anaesthetic and saline solution is infiltrated around the long saphenous vein. Place the patient in Trendelenburg position with approximately 20° of head-down tilt. Under ultrasound guidance, starting at the knee and working towards the groin, inject saline around the vein. Adequate tumescence is achieved when on ultrasound the vein with the contained catheter is sitting free of surrounding tissues in a sea of saline. Some systems have a temperature probe at the tip, which falls to room temperature as tip tumescence is achieved. In total about 500 ml of saline is used.

8. The machine is then armed and the heat delivered at the catheter tip. Appropriate eye protection is worn by staff and patient before activating the laser. The catheter is slowly withdrawn, closing the vein behind it. Whether this is a continuous withdrawal or pulsed depends on the system used. Digital pressure is applied along the length of the vein treated to ensure good contact with the catheter, which is confirmed with ultrasound.

9. Following the procedure it is the surgeon’s preference as to whether multiple avulsions are also undertaken. The lower limb is dressed with compression bandaging or hosiery.

ULTRASOUND-GUIDED FOAM SCLEROTHERAPY

Appraise

1. The foam causes an inflammatory reaction in the vein wall, destroying the vein lumen and blocking the vein.

2. When consenting the patient, ensure they are aware of the risks of superficial thrombophlebitis (sometimes treated subsequently by stab incisions over the vein and removing the clot), brown pigmentation, deep vein thrombosis, skin ulceration, allergic reaction to sclerosant and visual disturbances. Stroke has been reported in only two cases, due to high volume injection and a patent foramen ovale.

3. It is usually best to use foam sclerotherapy for patients with moderate-sized incompetent saphenous veins. It is therefore best suited to residual incompetent saphenous vein branches.

4. The procedure is undertaken in a clinic treatment room and not in theatre.

5. Rigorous compliance with compression for several days is vital for success.

Action

1. With the patient supine in negative Trendelenburg position, under aseptic conditions, the incompetent long saphenous vein is identified using ultrasound and cannulated in the calf as described above.

2. The sclerosant is foamed by passing 5 ml of sclerosant (Fibrovein 1%) back and forth between two 20-ml syringes, each containing 10 ml of carbon dioxide plus oxygen, via a three-way tap.

3. The leg is elevated and all blood removed from the collapsed long saphenous vein by milking the vessel from knee to groin.

4. The sclerosant is then injected slowly via the cannula into the saphenous vein. Its course along the vein is monitored by ultrasound. During this the patient is asked to bend their ankles up and down to increase the blood flow in the deep veins.

5. When the foam has filled the entire saphenous vein, the top end of the vein is compressed with the ultrasound probe to keep the foam in the superficial veins.

6. Once enough foam has been injected, the needle(s) are removed and pieces of sponge applied to the leg along the course of the long saphenous vein, followed by a bandage to compress the treated veins (such as Panalast or Colband). A full thigh-length elastic compression stocking is then put on top of this, with a waist attachment to ensure it stays in place.

7. The sponge, bandage and stocking are kept on continuously for 5 days. After this the sponges and bandage are removed and the stocking worn for a further 7 days.

AVULSION OF SUPERFICIAL VARICOSITIES

Appraise

1. Excise large branch veins that are not in close proximity to the saphenous or perforator systems to prevent unsightly local recurrences and provide a satisfactory cosmetic result.

2. Carefully mark out the superficial varicose veins preoperatively in the standing patient, as varicosities are not visible when the patient is anaesthetized and the legs are elevated.

Action

1. Make minute stab incisions over the course of tributaries in the direction of skin tension lines. Draw out a loop of vein by gentle blunt dissection, using specially designed hooks or mosquito artery forceps.

2. Divide the loop between mosquito forceps and tease out the vein in either direction by exerting steady traction and gentle blunt dissection under the skin with fine mosquito forceps.

3. Employ a gentle circular motion on the forceps to help separate the tethering fibrous tissue from the vein.

4. Release traction when the vein starts to stretch, and at this point ligate both ends. Alternatively, continue the traction until the vein breaks, controlling bleeding by local pressure until traumatic venospasm develops.

5. Place incisions 5 cm apart along the course of each tributary. This technique can be used to remove a long segment of varicose vein through 3–5 small incisions.

SURGICAL MANAGEMENT OF RECURRENT VARICOSE VEINS

Appraise

1. Recurrent varicose veins are veins that have become varicose after the original treatment. In contrast, residual varicose veins refer to those that were not treated at the original procedure (Fig. 24.5).

2. The causes of recurrent veins include:

Disease progression, with the development of new venous incompetence between the deep and superficial venous system

Disease progression, with the development of new venous incompetence between the deep and superficial venous system

Inadequate primary procedure, if the tributaries are left unligated, especially in the presence of a dual saphenous system that was not recognized or removed

Inadequate primary procedure, if the tributaries are left unligated, especially in the presence of a dual saphenous system that was not recognized or removed

Development of new bridging channels (neovascularization): collaterals may develop following simple ligation, reconnecting the deep veins to the saphenous vein.

Development of new bridging channels (neovascularization): collaterals may develop following simple ligation, reconnecting the deep veins to the saphenous vein.

3. The indications to treat recurrent varicose veins are similar to those for primary varicose veins, but the risk of complications is higher.

4. Diligently examine the varicosities, looking carefully for the scars of a previous operation.

5. Duplex ultrasound is essential to detect reflux in the saphenous veins and in large calf perforators.

6. The same techniques are available for removing incompetent veins as are employed for primary veins (described above). However, open surgical re-exploration, although technically more complete, can be difficult and lead to complications. Recurrent varicose veins are often thin-walled, multiple and easily damaged. Haemorrhage from torn veins can be severe. Persistent lymph leak can occur and damage to local structures such as nerves and vessels is a risk. For this reason, if possible, an endovenous ablation or sclerotherapy occlusion is the treatment of choice.

OPEN SURGERY FOR GROIN RECURRENCES

Action

1. Make an adequate incision to ensure good operative access. Incise in the groin crease centred on the saphenofemoral junction, 5 cm in length, extending laterally over the femoral pulse.

2. To reduce the risk of bleeding employ an approach through previously undissected tissue planes, which enables anatomical landmarks and vascular control to be established before tackling the recurrent varices. Expose the anterior surface of the femoral artery to facilitate access to the femoral vein.

3. Approach the saphenofemoral junction from the lateral side through relatively normal tissues. Open the femoral sheath to expose the anterior surface of the femoral artery.

4. Carefully dissect medially and expose the anterior surface of the femoral vein. Dissect it clean and locate the saphenofemoral junction.

5. Clear the saphenous stump on all sites close to the femoral vein until you can pass a Lahey forceps around it. Ligate it with 2/0 absorbable suture before dividing it. For added safety, transfix the stump.

6. Ligate all tributaries individually with 2/0 absorbable suture and divide them.

7. Strip the long saphenous vein if it is still present and avulse all superficial varicose veins in the usual manner.

Complications

1. Second operations are always more difficult than the primary procedure. If you do not fully display the anatomy it is easy to damage the major vessels.

2. Take care not to damage the femoral nerve during the lateral approach.

3. Lymphocele or lymph fistula may develop postoperatively, but usually resolves spontaneously.

SAPHENOPOPLITEAL RECURRENCES

Action

1. Deepen the incision through the subcutaneous tissues.

2. Identify the popliteal artery and vein well above the previous scar tissue and trace them down until you are able to identify the stump of the short saphenous vein.

3. Divide and ligate all the tributaries entering the popliteal vein, and especially the stump of the short saphenous vein.

4. Strip out any residual short saphenous vein or perform multiple avulsions.

OPERATIONS FOR DEEP VEIN THROMBOSIS

Appraise

1. There are very few indications for open deep vein surgery. Anticoagulant treatment is commonly used for the treatment of deep vein thrombosis (DVT).

2. There are two forms of deep vein intervention:

Venous thrombectomy is usually performed to remove a fresh (less than 5 days old), loose and non-adherent thrombus.

Venous thrombectomy is usually performed to remove a fresh (less than 5 days old), loose and non-adherent thrombus.

Insertion of filters to ‘lock in’ thrombus and prevent pulmonary embolism.

Insertion of filters to ‘lock in’ thrombus and prevent pulmonary embolism.

3. Operations are not indicated when the thrombus is more than 5 days old, fixed or totally occlusive. Surgery is also inappropriate when the thrombus is confined to the calf. These patients are best treated with anticoagulants.

4. Treat the uncommon complication of venous pregangrene (phlegmasia caerulen dolens) and gangrene by catheter-directed thrombolysis or venous thrombectomy.

5. Procedures to lock in the thrombus are indicated if anticoagulation is an unacceptable risk, e.g. prior to major abdominal surgery, or ineffective, especially when repeated pulmonary emboli occur despite adequate anticoagulant treatment.

6. Procedures to lock in the thrombus are thought to lower the mortality from pulmonary embolism in patients with loose propagated thrombus extending into the femoral or abdominal veins, although this has never been tested in a prospective randomized trial.

ILIOFEMORAL VENOUS THROMBECTOMY

Prepare

1. Be warned this can be a significant operation for surgeon and patient.

2. Commence treatment dose intravenous heparin before going to theatre.

3. Have a radiographically-placed IVC filter in situ (see below)

4. Patients are usually unwell and general anaesthetic is preferred, using endotracheal intubation and positive-pressure ventilation to stop any loose thrombi being propagated to the lungs, thus preventing intra-operative embolism.

5. Position the patient supine with the legs abducted on a radiolucent operating table.

6. Insert an indwelling urinary catheter to prevent phlebography from being obscured by the accumulation of dye in the bladder.

Access

1. Make a vertical incision over the femoral vein, extending from the midinguinal point to the centre of the thigh for 15–20 cm.

2. Divide the subcutaneous fat down to the deep fascia. The long saphenous vein lies medially, and can be traced up to the saphenofemoral junction.

3. Incise the deep fascia over the femoral vein in a vertical direction and gently dissect the femoral vein from the femoral artery on its lateral border. Use sharp dissection and avoid handling the vein if it contains loose thrombus.

4. Gently pass Silastic slings around the femoral vein above and below the profunda femoris vein, which is also snared.

Action

If thrombus is present in the iliac vein

1. Tip the operating feet down (30°) to ensure caudal blood flow in the vein and minimize the risk of pulmonary embolism.

2. Administer 5000 units of heparin and make a short transverse venotomy. When the loose thrombus has been flushed out of the venotomy by retrograde flow, pass a large Fogarty venous thrombectomy catheter (size 6–8 F) into the inferior vena cava. Inflate the balloon with contrast medium and withdraw it under fluoroscopic control while reducing the balloon diameter until it lies against the orifice of the common iliac vein. Beware of inadvertent insertion into a lumbar vein. Tighten the Silastic tubing around the catheter to prevent troublesome back-bleeding.

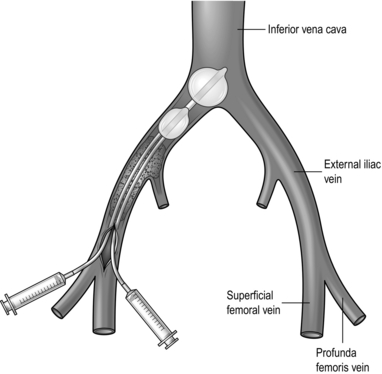

3. Pass a second large Fogarty catheter past the iliac thrombus, inflate the balloon and withdraw it to extract the thrombus. Repeat this until no further thrombus is obtained (Fig. 24.6).

Fig. 24.6 Iliac venous thrombectomy.

4. When all the thrombus appears to have been removed, deflate the caval balloon slightly and withdraw it to remove any loose thrombus that it has trapped.

5. Infuse heparinized saline into the iliac vein and ensure that all the thrombus has been removed. Confirm this using completion phlebography.

6. Residual thrombus may be compressed against the vein wall by deploying a stent.

7. Remove any distal thrombus by the technique described above and close the venotomy with a continuous 6/0 polypropylene suture.

8. Close the wound in layers. Continue systemic anticoagulation postoperatively.

If thrombus is present in the femoral vein

1. Give 5000 units of heparin.

2. Apply bulldog clamps on the proximal femoral and superficial femoral veins. Pass a suitable Fogarty venous thrombectomy catheter (4–5F) through a transverse venotomy as far distally as competent valves allow. The catheter rarely passes far down the leg.

3. Pull up the Silastic sling to prevent back-bleeding while the catheter is passed and withdrawn.

4. Inflate the catheter balloon and withdraw it slowly, pulling out the loose thrombus.

5. Thrombus must also be removed by manual compression applied along the line of the veins of the calf and thigh muscle or by applying a sterile Esmarch bandage around the limb. Distal thrombus can theoretically be removed using a Fogarty venous thrombectomy catheter passed through a tibial vein.

6. When no more thrombus can be obtained, close the venotomy with a 6/0 polypropylene suture and the wound in layers.

Postoperative care

1. Keep the patient on subcutaneous, low-molecular-weight heparin and allow mobilization while wearing a compression stocking on the day after surgery.

2. Start an oral anticoagulant until therapeutic range is achieved. The required duration of oral anticoagulation is variable and will be determined by the pathology identified.

3. Advise the patient to wear graduated compression stockings to prevent the development of post-thrombotic syndrome.

INSERTION OF VENA CAVAL FILTERS

Appraise

1. There is no indication for open caval clipping. However, it is helpful to remember in times of uncontrollable caval bleeding secondary to trauma that the IVC can be ligated with only a 30% incidence of lower limb oedema.

2. The insertion of a vena caval filter should only be considered when there is a contraindication to anticoagulation (for example imminent surgery, intolerance of or side-effects to warfarin or pulmonary embolus despite adequate anticoagulation).

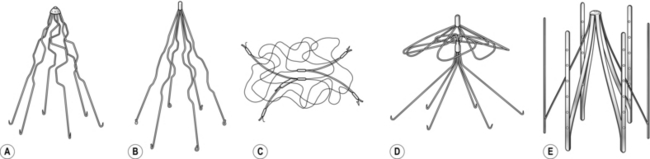

3. Vena cava filters (Fig. 24.7) are inserted percutaneously into the inferior vena cava, via the groin or internal jugular vein over a guide-wire under local anaesthesia, rather than by open surgical insertion.

4. Some filters are temporary and consideration should be given to when they should be removed.

Access

1. As when inserting a central line, with the patient in a head down position and under ultrasound guidance, percutaneously cannulate the right internal jugular vein using a hollow needle through a small incision placed over the sternomastoid muscle, 2 cm above the clavicle. Pass a guide wire through the needle into the vein and with fluoroscopy confirm its position into the superior vena cava, atrium and inferior vena cava.

2. Pass a dilating sheath over the guide wire if necessary.

3. Insert the catheter containing the filter over the wire through the sheath, and screen it into the inferior vena cava using an image intensifier.

4. Prevent blood loss by placing a finger over the sheath, but keep the patient head down to prevent air entry.

5. When the catheter lies in the vena cava below the renal veins, deploy the filter, which attaches to the side-wall of the cava by a series of tiny barbs around its periphery. These barbs are designed to prevent the filter from migrating, which is the major complication of the procedure. Incorrect siting of the filter may also be a problem. The mode of filter deployment depends on the filter used: many are re-deployable if positioning is not perfect.

Postoperative

1. Maintain intravenous heparinization for a minimum of 48 hours after the procedure unless there is a strong contraindication.

2. All patients who have had a severe deep vein thrombosis need to wear graduated compression elastic stockings to prevent the development of post-thrombotic syndrome and venous ulceration in the future.

OPERATIONS FOR VENOUS ULCER AND POST-THROMBOTIC SYNDROME

Appraise

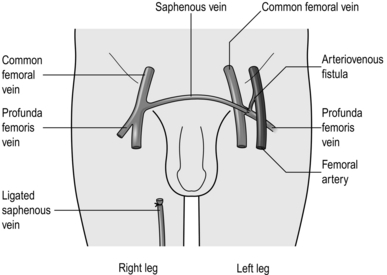

Saphenous transposition (Palma operation) (Fig. 24.8)

Fig. 24.8 Saphenous transposition.

1. This is valuable for symptomatic venous claudication but use it only:

When the femoral venous pressure rises on exercise

When the femoral venous pressure rises on exercise

In the absence of naturally developed suprapubic collateral channels, which are often massive.

In the absence of naturally developed suprapubic collateral channels, which are often massive.

2. Dissect the contralateral saphenous vein down and mobilize it until it can be taken through a suprapubic tunnel to anastomose it to the common femoral or profunda femoris vein of the opposite limb, thus providing a collateral channel for a single blocked iliac segment.

3. Patency of the bypass may be improved with an arteriovenous fistula.

SPLIT SKIN GRAFT FOR VENOUS ULCERATION

Prepare

1. The ulcer base should be optimized by bed rest and intensive antiseptic cleaning.

2. The procedure is performed under local anaesthesia. Ensure that the ulcer is clear of infection by microscopy and culture before attempting grafting. Prepare the ulcer by excising the basal tissues with a Humby or Braithwaite knife, using tangential excision, until healthy tissue is reached.

3. Meshed split skin grafts (2:1 ratio) should be applied to the dry base using staples. ‘Postage stamp’ or pinch grafts can be used as an alternative.

4. Reapply compression dressings in theatre. Failure to do so will result in graft loss. If the leg is very oedematous despite pre-grafting compression, a negative-vacuum pump dressing can be applied over the graft, under the compression bandage.

LYMPHATIC SURGERY

Appraise

1. The majority of patients with primary and secondary lymphoedema respond readily to active conservative treatment. Regular leg elevation, elastic support and massage are all that are needed to maintain an acceptable level of swelling.

2. If, despite adequate conservative management, the patient develops severe limb swelling that interferes with mobility, consider operative treatment.

3. Such surgery should only be performed by lymphoedema specialists as part of a multidisciplinary team.

4. Perform bilateral isotope or contrast lymphography in patients considered for lymphatic surgery. This displays anatomical information about the site and cause of the lymphatic impairment and may help to select the appropriate surgical procedure. Most patients with primary lymphoedema have slowly progressive distal lymphatic hypoplasia. A smaller number suffer progressive fibrosis of the proximal lymph nodes, leading to obstruction. The distal lymphatics also slowly disappear in these patients. A few have obstruction of the thoracic duct, and a few have megalymphatics with valvular incompetence.

5. Surgery for lymphoedema can be divided into two broad approaches:

Reduction operations. The lymphoedematous subcutaneous tissue and skin are excised; these procedures can be used to treat all forms of lymphoedema.

Reduction operations. The lymphoedematous subcutaneous tissue and skin are excised; these procedures can be used to treat all forms of lymphoedema.

Bypass operations. These procedures have not found widespread acceptance in clinical practice. They bypass sites of localized lymphatic obstruction, and are suitable for patients with a proximal occlusion and normal distal lymphatics. The mesenteric bridge operation may be applicable for patients with obstruction of the femoral or pelvic lymph nodes. Lymphovenous anastomosis has also been proposed as a means of bypassing lymphatic obstruction. These will not be considered further.

Bypass operations. These procedures have not found widespread acceptance in clinical practice. They bypass sites of localized lymphatic obstruction, and are suitable for patients with a proximal occlusion and normal distal lymphatics. The mesenteric bridge operation may be applicable for patients with obstruction of the femoral or pelvic lymph nodes. Lymphovenous anastomosis has also been proposed as a means of bypassing lymphatic obstruction. These will not be considered further.

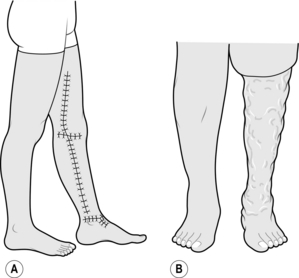

6. Fully inform the patients about the surgery that is proposed for them. They should have a realistic appreciation of the expected functional and cosmetic results (Fig. 24.9). Patients must understand that lymphatic surgery is palliative, and further surgery may be necessary at a later date.

REDUCTION OPERATIONS

Prepare

1. Minimize swelling prior to surgery with a period of bed rest and limb elevation and by compression bandaging.

2. Eradicate sepsis prior to surgery. Swab possible sites of infection on admission and send for microscopy and culture. Antibiotics are prescribed selectively. Clean the limb twice daily in an antiseptic bath, paying special attention to the skin creases. Tinea pedis commonly develops between swollen lymphoedematous toes. Take a skin scraping if the diagnosis is suspected and prescribe a suitable antifungal treatment such as terbinafine.

3. Perform reduction operations under general anaesthesia with the patient in a supine position.

4. Position the limb to facilitate operative access. For procedures on the medial side of the leg, elevate the limb to about 30–45° and widely abduct it. This is best achieved by inserting a Kirschner wire through the calcaneum and connecting a metal stirrup to the wire on each side of the foot before elevating the leg with a pulley system. Lower the foot of the operating table and flex the contralateral knee. Stand on the medial side of the leg, between the limb and the operating table.

5. To reduce blood loss, place a tourniquet around the upper thigh and inflate it to 350 mmHg after the limb has been exsanguinated with an Esmarch bandage. Note the time of tourniquet application.

CHARLES’ OPERATION

Action

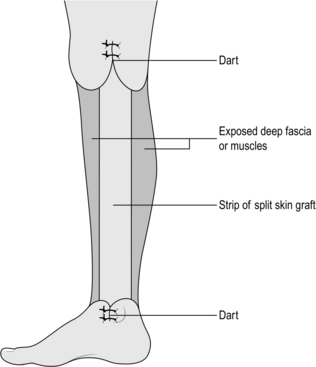

1. Described by the English surgeon R.H. Charles in 1912, it aims to excise the lymphoedematous skin and subcutaneous tissue between the knee and the ankle, including the dorsum of the foot. This is the procedure of choice when the skin is greatly thickened and abnormal. Preserve skin cover over the knee and the ankle in order to retain the mobility of these joints (Fig. 24.10).

Fig. 24.10 Charles’ leg reduction operation.

2. Cover the exposed deep fascia of the leg with split skin grafts taken from the trunk or from the contralateral limb.

3. Take darts of redundant skin and subcutaneous tissue from the medial and lateral sides of the leg at the knee and ankle to prevent a marked ‘step’ effect and an ugly appearance similar to pantaloons.

4. Staple the skin grafts to the deep fascia and cover them with non-adherent dressings and thick cotton wool held in place with crepe bandages.

5. Plan to maintain elevation of the limb for 1 week, before removing the bandages and inspecting the limb.

Complications

1. Delayed healing may be a problem if the split skin graft fails to take.

2. Hypertrophic and keloid scars sometimes develop in the grafted skin. Hypertrophic scarring is often associated with chronic infection: treat it by regular cleansing and antibiotics. Prominent tissue can be shaved off with a skin-graft knife. Keloid scars may need to be excised and re-grafted.

3. The Charles’ operation is very effective at reducing the excessive bulk of lymphoedematous tissues around the leg and improving mobility. The final appearance is, however, often bizarre, with swollen feet and thighs joined by a narrow calf.

HOMANS’ OPERATION

Appraise

1. John Homans (1877–1954) was Professor of Surgery at Harvard, Boston. Lymphoedematous swelling of moderate severity in limbs with relatively normal skin is best treated by the operation he described.

2. The operation is usually first performed on the medial side of the limb, but the tissues on the lateral side can also be reduced. If you intend to operate on both sides, stage the procedures over 3 months, otherwise skin viability is compromised if the excision extends beyond half the circumference of the limb.

3. Aim to excise lymphoedematous subcutaneous tissues and redundant skin from one side of the limb. When the limb is viewed in cross-section the excised tissues appeared wedge-shaped (Fig. 24.11A).

4. Raise the skin flaps first, then excise the underlying fat. Overlap the skin flaps to decide how much redundant skin needs to be excised.

Action

1. Make a longitudinal incision from a hand’s breadth below the knee to a similar distance above the ankle, beginning just behind the posterior border of the tibia, ending anterior to the medial malleolus. Transverse incisions may also be necessary at each of the longitudinal incisions (Fig. 24.11B).

2. Raise skin flaps in an anterior and posterior direction, increasing in thickness towards the base of the flap. Extend the flaps for 10–12 cm around the leg or as far as the midline in each direction.

3. Excise all the underlying subcutaneous tissue not included in the skin flaps down to the deep fascia. Excise any superficial veins and cutaneous nerves with this block of tissue.

4. Overlap the flaps and mark the redundant skin to be excised, allowing for primary closure of the incision. Having excised the skin, if necessary, trim the skin flaps in a longitudinal direction. Excise darts at the ankle and knee to avoid dog-ears. The darts should meet the transverse incision at a different point from the longitudinal incision to reduce the chance of wound breakdown. The upper dart may be extended a considerable distance up the limb towards the groin to allow a simple wedge excision of the skin and subcutaneous tissues of the thigh, as shown in Figure 24.11.

5. Close the skin with interrupted sutures or staples over suction drains.

6. Apply a non-adherent dressing to the suture lines and dress the whole limb from the base of the toes with cotton wool and crepe bandages.

Complications

1. Although the early results appear good, many patients develop recurrent limb swelling, eventually approaching preoperative dimensions.

2. Repeated reduction surgery may be necessary. Combined with good elastic stocking support, this often produces an acceptable limb, although its size is rarely normal.

3. Skin necrosis, infection and haematoma formation are all recognized problems.

Adam, D.J., Bello, M., Hartshorne, T., et al. Role of superficial venous surgery in patients with combined superficial and segmental deep venous reflex. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2003; 25:469–472.

Amarigi, S.V., Lees, T.A. Elastic compression stockings for prevention of deep vein thrombosis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. (3):2000. [CD001484].

Barwell, J.R., Davies, C.E., Deacon, J., et al. Comparison of surgery and compression with compression alone in chronic venous ulceration (ESCHAR study): randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2004; 363:1854–1859.

Browse, N. Diseases of the Veins, 2nd ed. London: Arnold; 1999.

Burnand, K. The New Aird’s Companion in Surgical Studies, 2nd ed. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone; 1998.

Campisi, C., Boccardo, F., Zilli, A., et al. Long-term results after lymphatic-venous anastomoses for the treatment of obstructive lymphedema. Microsurgery. 2001; 21:135–139.

Corrales, N.E., Irvine, A., McGuiness, C.L., et al. Incidence and pattern of long saphenous vein duplication and its possible implications for recurrence after varicose vein surgery. Br J Surg. 2002; 89:323–326.

Dwerryhouse, S., Davies, B., Harradine, K., et al. Stripping the long saphenous vein reduces the rate of reoperation for recurrent varicose veins: five-year results of a randomized trial. J Vasc Surg. 1999; 29:589–592.

Elias, M., Frasier, K.L. Minimally invasive vein surgery: its role in the treatment of venous stasis ulceration. Am J Surg. 2004; 188:26–30.

Kalra, M., Gloviczki, P. Surgical treatment of venous ulcers: role of subfascial endoscopic perforator vein ligation. Surg Clin North Am. 2003; 83:671–705.

Serror, P. Sural nerve lesions: a report of 20 cases. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2002; 81:876–880.

Zamboni, P., Cisno, C., Marchetti, F., et al. Minimally invasive surgical management of primary venous ulcers vs. compression treatment: a randomized clinical trial. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2003; 25:313–318.

Zierau, U.T., Kullmer, A., Kunkel, H.P. Stripping the Giacomini vein: pathophysiologic necessity or phlebosurgical games? Vasa. 1996; 25:142–147.