Chapter 161 Vasculitis Syndromes

Childhood vasculitis encompasses a broad spectrum of diseases that share a common denominator, inflammation of the blood vessels. The pathogenesis of the vasculitides is generally idiopathic; some forms of vasculitis are associated with infectious agents and medications, and others may occur in the setting of preexisting autoimmune disease. The pattern of vessel injury provides insight into the form of vasculitis and serves as a framework to delineate the different vasculitic syndromes. The distribution of vascular injury includes small vessels (capillaries, arterioles, and postcapillary venules), medium vessels (renal arteries, mesenteric vasculature, and coronary arteries), and large vessels (the aorta and its proximal branches). Additionally, some forms of small vessel vasculitis are characterized by the presence of antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies (ANCAs), whereas others are associated with immune complex deposition in affected tissues. A combination of clinical features, histologic appearance of involved vessels, and laboratory data is utilized to classify vasculitis (Tables 161-1 to 161-3).

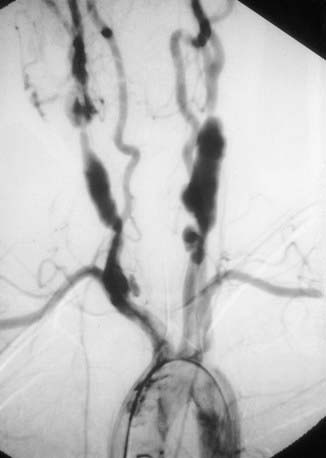

Table 161-1 CLASSIFICATION OF CHILDHOOD VASCULITIS

I. PREDOMINANTLY LARGE VESSEL VASCULITIS

II. PREDOMINANTLY MEDIUM VESSEL VASCULITIS

III. PREDOMINANTLY SMALL VESSEL VASCULITIS

IV. OTHER VASCULITIDES

* Associated with antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody.

Adapted from Ozen S, Ruperto N, Dillon MJ, et al: EULAR/PReS endorsed consensus criteria for the classification of childhood vasculitides, Ann Rheum Dis 65:936–941, 2006.

Table 161-2 FEATURES THAT SUGGEST A VASCULITIC SYNDROME

CLINICAL FEATURES

LABORATORY FEATURES

From Cassidy JT, Petty RE: Textbook of pediatric rheumatology, ed 5, Philadelphia, 2005, Elsevier/Saunders.

Bibliography

Dedeoglu F, Sundel RP: Vasculitis in children, Rheum Dis Clin North Am 33:555–583, 2007.

161.1 Henoch-Schönlein Purpura

Pathology

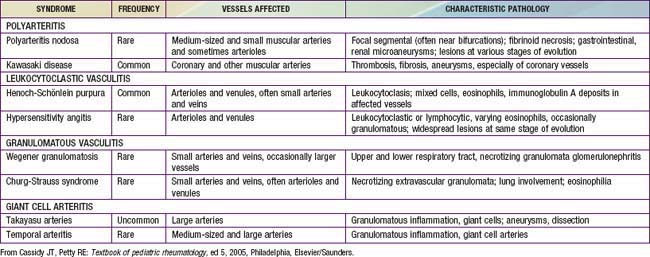

Skin biopsies demonstrate vasculitis of the dermal capillaries and postcapillary venules. The inflammatory infiltrate includes neutrophils and monocytes. Renal histopathology typically shows endocapillary proliferative glomerulonephritis, ranging from a focal segmental process to extensive crescentic involvement. In all tissues, immunofluorescence identifies IgA deposition in walls of small vessels (see Fig. 161-1), accompanied to a lesser extent by deposition of C3, fibrin, and IgM.

Clinical Manifestations

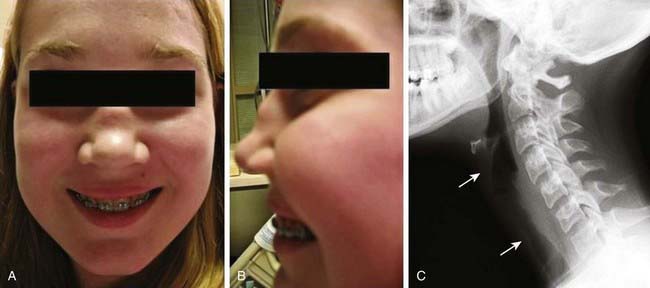

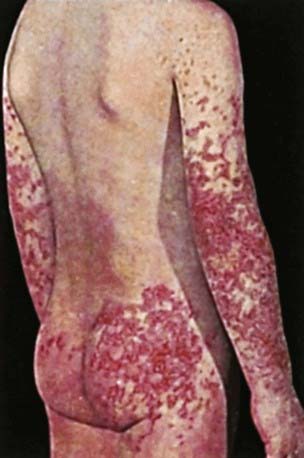

The hallmark of HSP is its rash: palpable purpura starting as pink macules or wheals and developing into petechiae, raised purpura, or larger ecchymoses. Occasionally, bullae and ulcerations develop. The skin lesions are usually symmetric and occur in gravity-dependent areas (lower extremities) or on pressure points (buttocks) (Figs. 161-1 and 161-2). The skin lesions often evolve in groups, typically lasting 3-10 days, and may recur up to 4 mo after initial presentation. Subcutaneous edema localized to the dorsa of hands and feet, periorbital area, lips, scrotum, or scalp is also common.

Figure 161-2 Henoch-Schönlein purpura.

(From Korting GW: Hautkrankheiten bei Kindern und Jungendlichen, ed 3, Stuttgart, 1982, FK Schattaur Verlag.)

Renal involvement occurs in up to 50% of children with HSP, manifesting as hematuria, proteinuria, hypertension, frank nephritis, nephrotic syndrome, and acute or chronic renal failure. Progression to end-stage renal disease is uncommon in children (1-2%) (see Chapter 509 for more detailed discussion of HSP renal disease).

Diagnosis

The diagnosis of HSP is a clinical one and is often straightforward when the typical rash is present. However, in at least 25% of cases, the rash appears after other manifestations, making early diagnosis challenging. Classification criteria for HSP are summarized in Table 161-4. The differential diagnosis for HSP depends on specific organ involvement but usually includes other small vessel vasculitides, infections, coagulopathies, and other acute intra-abdominal processes.

Table 161-4 CLASSIFICATION CRITERIA FOR HENOCH-SCHÖNLEIN PURPURA*

AMERICAN COLLEGE OF RHEUMATOLOGY CLASSIFICATION CRITERIA†

EUROPEAN LEAGUE AGAINST RHEUMATISM/PEDIATRIC RHEUMATOLOGY EUROPEAN SOCIETY CRITERIA‡

* Classification criteria are developed for use in research and not validated for clinical diagnosis.

† Developed for use in adult and pediatric populations. Adapted from Mills JA, Michel BA, Bloch DA, et al: The American College of Rheumatology 1990 criteria for classification of Henoch-Schonlein purpura, Arthritis Rheum 33:1114–1121, 1990.

‡ Developed for use in pediatric populations only.

Adapted from Ozen S, Ruperto N, Dillon MJ et al: EULAR/PReS endorsed consensus criteria for the classification of childhood vasculitides, Ann Rheum Dis 65:936–941, 2006.

Acute hemorrhagic edema (AHE), an isolated cutaneous leukocytoclastic vasculitis that affects infants <2 yr of age, resembles HSP clinically. AHE manifests as fever; tender edema of the face, scrotum, hands, and feet; and ecchymosis (usually larger than the purpura of HSP) on the face and extremities (Fig. 161-3). The trunk is spared, but petechiae may be seen in mucous membranes. The patient usually appears well except for the rash. The platelet count is normal or elevated, and the urinalysis results are normal. The younger age, the nature of the lesions, absence of other organ involvement, and a biopsy may help distinguish AHE from HSP.

Coppo R, Mazzucco G, Cagnoli L, et al. Long term prognosis of Henoch-Schonlein nephritis in adult and children. Italian Group of Renal Collaborative Study on Henoch-Schonlein purpura. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 1997;12:2277-2283.

Davin JC, Weening JJ. Henoch-Schönlein purpura nephritis: an update. Eur J Pediatr. 2001;160:689-695.

Donnithorne KJ, Atkinson P, Hinze CH, et al. Rituximab therapy for severe refractory chronic Henoch-Schönlein purpura. J Pediatr. 2009;155:136-139.

Hoffman GS. Therapeutic interventions for systemic vasculitis. JAMA. 2010;304(21):2413-2414.

Jauhola O, Ronkainen J, Koskimies O, et al. Clinical course of extrarenal symptoms in Henoch-Schönlein purpura: a 6-month prospective study. Arch Dis Child. 2010;95:871-876.

Jauhola O, Ronkainen J, Koskimies O, et al. Renal manifestations of Henoch-Schönlein purpura in a 6-month prospective study of 223 children. Arch Dis Child. 2010;95:877-882.

Mir S, Yavascan O, Mutlubas F, et al. Clinical outcome in children with Henoch-Schönlein nephritis. Pediatr Nephrol. 2007;22:64-70.

Peru H, Soylemezoglu O, Bakkaloglu SA, et al. Henoch Schönlein purpura in childhood: clinical analysis of 254 cases over a 3-year period. Clin Rheumatol. 2008;27:1087-1092.

Ronkainen J, Koskimies O, Ala-Houhala M, et al. Early prednisone therapy in Henoch-Schonlein purpura: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. J Pediatr. 2006;149:241-247.

Tizard EJ, Hamilton-Ayres MJJ. Henoch-Schönlein purpura. Arch Dis Child Educ Pract Ed. 2008;93:1-8.

Weiss PF, Feinstein JA, Luan X, et al. Effects of corticosteroid on Henoch-Schönlein purpura: a systematic review. Pediatrics. 2007;120:1079-1087.

Weiss PF, Klink AJ, Hexem K, et al. Variation in inpatient therapy and diagnostic evaluation of children with Henoch-Schönlein purpura. J Pediatr. 2009;155:812-818.

161.2 Takayasu Arteritis

Diagnosis

Specific pediatric criteria for TA have been proposed, as summarized in Tables 161-5 and 161-6. Radiographic demonstration of large vessel vasculitis is necessary. A thorough physical examination is required to detect an aortic murmur, diminished or asymmetric pulses, and vascular bruits. Four extremity blood pressures should be measured >10 mm Hg; asymmetry in systolic pressure is indicative of disease.

Table 161-5 PROPOSED CLASSIFICATION CRITERIA FOR PEDIATRIC-ONSET TAKAYASU ARTERITIS

Angiographic abnormalities (conventional, CT, or magnetic resonance angiography) of the aorta or its main branches and at least one of the following criteria:

Adapted from Ozen S, Ruperton N, Dillon MJ, et al: EULAR/PReS endorsed consensus criteria for the classification of childhood vasculitides, Ann Rheum Dis 65:936–941, 2006.

Table 161-6 PATTERNS OF ARTERIAL INVOLVEMENT IN TAKAYASU ARTERITIS

| TYPE | INVOLVED ARTERIES |

|---|---|

| I |

Adapted from Hata A, Noda M, Moriwaki R, et al: Angiographic findings of Takayasu arteritis: new classification, Int J Cardiol 54(Suppl):S155–S163, 1996.

Laboratory Findings

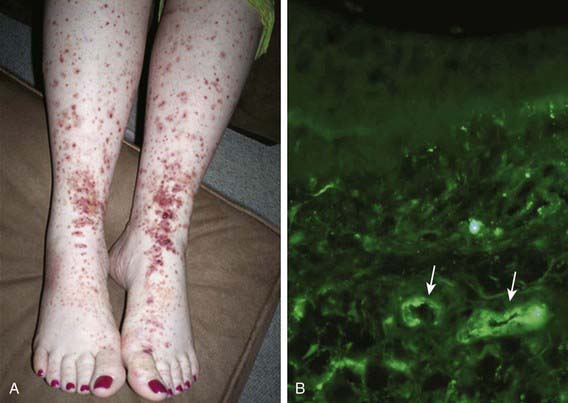

Radiographic assessment is essential to establish large vessel arterial involvement. The gold standard remains conventional arteriography of the aorta and major branches, including carotid, subclavian, pulmonary, renal, and mesenteric branches. Conventional arteriography can identify luminal defects, including dilation, aneurysms, and stenoses, even in smaller vessels such as the mesenteric arteries. Figure 161-4 shows a conventional arteriogram in a child with TA. Although not yet thoroughly validated in TA, magnetic resonance angiography (MRA) and CT angiography (CTA) are gaining acceptance and provide important information about vessel wall thickness and enhancement, although they may not image smaller vessels as well as conventional angiography. Positron emission tomography (PET) may detect vessel wall inflammation but has not been studied extensively. Ultrasound with duplex color-flow Doppler imaging also identifies vessel wall thickening and assesses arterial flow. Echocardiography is recommended to assess for aortic valvular involvement. Serial vascular imaging is usually necessary to assess response to treatment and to detect progressive vascular damage.

Cakar N, Yalcinkaya F, Duzova A, et al. Takayasu arteritis in children. J Rheumatol. 2008;35:913-919.

Filocamo G, Buoncompagni A, Viola S, et al. Treatment of Takayasu’s arteritis with tumor necrosis factor antagonists. J Pediatr. 2008;153:432-434.

Kalangos A, Christenson JT, Cikirikcioglu M, et al. Long-term outcome after surgical intervention and interventional procedures for the management of Takayasu’s arteritis in children. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2006;132:656-664.

Maksimowicz-McKinnon K, Clark TM, Hoffman GS. Limitations of therapy and a guarded prognosis in an American cohort of Takayasu arteritis patients. Arthritis Rheum. 2007;56:1000-1009.

Ozen S, Duzova A, Bakkaloglu A, et al. Takayasu arteritis in children: preliminary experience with cyclophosphamide induction and corticosteroids followed by methotrexate. J Pediatr. 2007;150:72-76.

Park MC, Lee SW, Park YB, et al. Clinical characteristics and outcomes of Takayasu’s arteritis: analysis of 108 patients using standardized criteria for diagnosis, activity assessment, and angiographic classification. Scand J Rheumatol. 2005;34:284-292.

Park MC, Lee SW, Park YB, et al. Serum cytokine profiles and their correlations with disease activity in Takayasu’s arteritis. Rheumatology. 2006;45:545-548. (Oxford)

161.3 Polyarteritis Nodosa and Cutaneous Polyarteritis Nodosa

Pathology

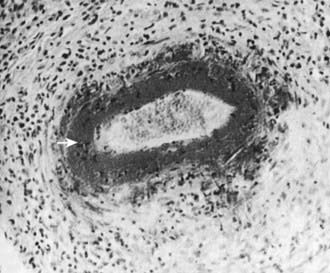

Biopsies show necrotizing vasculitis with granulocytes and monocytes infiltrating the walls of small and medium-sized arteries (Fig. 161-5). Involvement is usually segmental and tends to occur at vessel bifurcations. Granulomatous inflammation is not present, and deposition of complement and immune complexes is rarely observed. Different stages of inflammation are found, ranging from mild inflammatory changes to panmural fibrinoid necrosis associated with aneurysm formation, thrombosis, and vascular occlusion.

Diagnosis

The diagnosis of PAN requires demonstration of vessel involvement on biopsy or angiography. Biopsy of cutaneous lesions shows small or medium vessel vasculitis (see Fig. 161-5). Kidney biopsy in patients with renal manifestations may show necrotizing arteritis. Electromyography in children with peripheral neuropathy identifies affected nerves, and sural nerve biopsy may reveal vasculitis. Conventional arteriography is the gold standard diagnostic imaging study for PAN and reveals areas of aneurysmal dilatation and segmental stenosis, the classic “beads on a string” appearance (Fig. 161-6). MRA and CTA, less invasive imaging alternatives, are gaining acceptance but may not be as effective in identifying small vessel disease or in younger children.

Treatment

Oral (1-2 mg/kg/day) and intravenous pulse (30 mg/kg/day) corticosteroids are typically used, frequently in combination with oral or intravenous cyclophosphamide. If hepatitis B is identified, appropriate antiviral therapy should be initiated (Chapter 350). Most cases of cutaneous PAN can be treated with corticosteroids alone at doses of 1-2 mg/kg/day. If an infectious trigger for PAN is identified, antibiotic prophylaxis should be considered. Efficacy data are limited for the treatment of relapsing or refractory cutaneous disease, but dapsone, methotrexate, azathioprine, thalidomide, cyclosporine, and anti-TNF agents have been used successfully.

Dedeoglu F, Sundel RP. Vasculitis in children. Rheum Dis Clin North Am. 2007;33:555-583.

Jennette JC, Falk RJ, Andrassy K, et al. Nomenclature of systemic vasculitides: proposal of an international consensus conference. Arthritis Rheum. 1994;37:187-192.

Naumann-Bartsch N, Stachel D, Morhart P, et al. Childhood polyarteritis nodosa in autoimmune lymphoproliferative syndrome. Pediatrics. 2010;125:e169-e173.

Ozen S, Anton J, Arisoy N, et al. Juvenile polyarteritis: results of a multicenter survey of 110 children. J Pediatr. 2004;145:517-522.

Ozen S, Ruperto N, Dillon MJ, et al. EULAR/PReS endorsed consensus criteria for the classification of childhood vasculitides. Ann Rheum Dis. 2006;65:936-941.

Yalcinkaya F, Ozcakar B, Kasapcoupur O, et al. Prevalence of the MEFV gene mutations in childhood polyarteritis nodosa. J Pediatr. 2007;151:675-678.

161.4 ANCA-Associated Vasculitis

Pathology

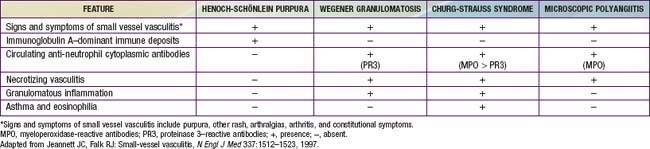

Necrotizing vasculitis is the cardinal histologic feature in WG and MPA. Kidney biopsies typically demonstrate crescentic glomerulonephritis with little or no immune complex deposition (“pauci-immune”), in contrast to biopsies from patients with SLE. Although granulomatous inflammation is common in WG and CSS, it is typically not present in MPA. Biopsies showing perivascular eosinophilic infiltrates distinguish CSS syndrome from both MPA and WG (Table 161-7).

Clinical Manifestations

Early disease course is characterized by nonspecific constitutional symptoms, including fever, malaise, weight loss, myalgias, and arthralgias. In WG, upper airway involvement can manifest as sinusitis, nasal ulceration, epistaxis, otitis media, and hearing loss. Lower respiratory tract symptoms include cough, wheezing, dyspnea, and hemoptysis. Pulmonary hemorrhage can cause rapid respiratory failure. Compared with WG in adults, childhood WG is more frequently complicated by subglottic stenosis (see Fig. 161-5). Inflammation-induced damage to the nasal cartilage can produce a saddle nose deformity (Fig. 161-7). Ophthalmic involvement includes conjunctivitis, scleritis, uveitis, optic neuritis, and invasive orbital pseudotumor (causing proptosis). Perineural vasculitis or direct compression on nerves by granulomatous lesions can cause cranial and peripheral neuropathies. Hematuria, proteinuria, and hypertension signal renal disease. Cutaneous lesions include palpable purpura and ulcers. Venous thromboembolism is a rare but potentially fatal complication of WG. The frequencies of organ system involvement throughout the disease course in WG are: respiratory tract, 84%; kidneys, 88%; joints, 44%; eyes, 60%; skin, 48%; sinuses, 56%; and nervous system, 12%.

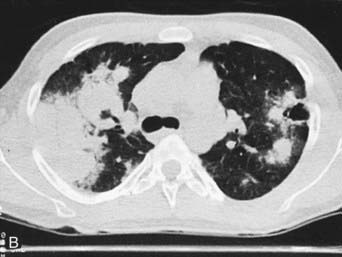

Diagnosis

WG should be considered in children who have recalcitrant sinusitis, pulmonary infiltrates, and evidence of nephritis. Chest radiography often fails to detect pulmonary lesions, and chest CT may show nodules, ground-glass opacities, mediastinal lymphadenopathy, and cavitary lesions (Fig. 161-8). The diagnosis is confirmed by the presence of anti–proteinase 3 (anti-PR3)–specific ANCAs (PR3-ANCAs) and the finding of necrotizing granulomatous vasculitis on pulmonary, sinus, or renal biopsy. The ANCA test result is positive in approximately 90% of children with WG, and the presence of anti-PR3 increases the specificity of the test.

Figure 161-8 Radiographs of lower respiratory tract disease in Wegener granulomatosis. A, A chest radiograph of a 14 yr old girl with Wegener granulomatosis and pulmonary hemorrhage. Extensive bilateral, fluffy infiltrates are visualized. B, CT scan of the chest in a 17 yr old boy with Wegener granulomatosis. Air space consolidation, septal thickening, and a single cavitary lesion are present.

(From Kuhn JP, Slovis TL, Haller JO: Caffey’s pediatric diagnostic imaging, ed 10, vol 1, Philadelphia, 2004, Mosby.)

(From Cassidy JT, Petty RE: Granulomatous vasculitis, giant cell arteritis and sarcoidosis. In Textbook of pediatric rheumatology, ed 3, Philadelphia, 1995, WB Saunders.)

Laboratory Findings

Elevated ESR and CRP values, leukocytosis, and thrombocytosis are present in most patients with an ANCA-associated vasculitis but are nonspecific. Anemia may be due to chronic inflammation or pulmonary hemorrhage. ANCA antibodies show two distinct immunofluorescence patterns: perinuclear (p-ANCAs) and cytoplasmic (c-ANCAs). In addition, ANCAs can also be defined by their specificity for PR3 or MPO antigen. As summarized in Table 161-4, WG is strongly associated with c-ANCAs/anti-PR3 antibodies.

Akikusa JD, Schneider R, Harvey EA, et al. Clinical features and outcome of pediatric Wegener’s granulomatosis. Arthritis Rheum. 2007;57:837-844.

Bosch X, Guilabert A, Espinosa G, et al. Treatment of antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody-associated vasculitis. JAMA. 2007;298:655-668.

Finkielman JD, Merkel PA, Schroeder D, et al. Antiproteinase 3 antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies and disease activity in Wegener granulomatosis. Ann Intern Med. 2007;147:611-619.

Frosch M, Foell D. Wegener granulomatosis in childhood and adolescence. Eur J Pediatr. 2004;163:425-434.

Kallenberg CG. Pathogenesis of PR3-ANCA associated vasculitis. J Autoimmun. 2008;30:29-36.

Levine D, Akikusa J, Manson D, et al. Chest CT findings in pediatric Wegener’s granulomatosis. Pediatr Radiol. 2007;37:57-62.

Pagnoux C, Mahr A, Hamidou MA, et al. Azathioprine or methotrexate maintenance for ANCA-associated vasculitis. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:2790-2802.

Wung PK, Stone JH. Therapeutics of Wegener’s granulomatosis. Nat Clin Pract Rheumatol. 2006;2:192-200.

161.5 Other Vasculitis Syndromes

In addition to the more common vasculitides discussed earlier in this chapter, other vasculitic conditions can occur in childhood, the most common of which is Kawasaki disease (discussed in Chapter 160). Hypersensitivity vasculitis is a cutaneous vasculitis triggered by medication or toxin exposure. The rash consists of palpable purpura or other nonspecific rash. Skin biopsies reveal characteristic changes of leukocytoclastic vasculitis (small vessels with neutrophilic perivascular or extravascular neutrophilic infiltration). Hypocomplementemic urticarial vasculitis involves small vessels and manifests as recurrent urticaria that resolves over several days but leaves residual hyperpigmentation. This condition is associated with low levels of complement component C1q and systemic findings that include fever, gastrointestinal symptoms, arthritis, and glomerulonephritis. Cryoglobulinemic vasculitis can complicate mixed essential cryoglobulinemia and is a small vessel vasculitis affecting skin, joints, kidneys, and lungs. Primary angiitis of the central nervous system (PACNS) represents vasculitis confined to the CNS and requires exclusion of other systemic vasculitides. Benign angiitis of the central nervous system (BACNS), also known as transient CNS angiopathy, represents a self-limited variant. Cogan syndrome is rare in children; its potential clinical manifestations include constitutional symptoms, inflammatory eye disease, vestibuloauditory dysfunction, arthritis, and aortitis.

Identification of these vasculitis syndromes requires a comprehensive history and physical exam. Other diagnostic considerations are outlined in Table 161-8. Although treatment is tailored to disease severity, treatment generally includes prednisone (up to 2 mg/kg/day) plus steroid-sparing immunosuppressive medications if necessary. For hypersensitivity vasculitis, withdrawal of the triggering medication or toxin is indicated if possible.

Table 161-8 DIAGNOSTIC CONSIDERATIONS FOR OTHER VASCULITIS SYNDROMES

| VASCULITIS SYNDROME | APPROACH TO DIAGNOSIS |

|---|---|

| Hypersensitivity vasculitis | Skin biopsy demonstrating leukocytoclastic vasculitis |

| Hypocomplementemic urticarial vasculitis |

CNS, central nervous system; CT, computed tomography; MR, magnetic resonance.