110 Vasculitis Syndromes

• A patient’s combined genetic predisposition and regulatory mechanisms control expression of the immune response to antigens.

• Negative test results for antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies do not exclude disease, nor do positive results indicate a specific syndrome.

• The combination of clinical, laboratory, biopsy, and radiographic findings usually points to a specific vasculitis syndrome.

• Definitive diagnosis of a vasculitic syndrome depends on demonstration of vascular involvement and may be accomplished by biopsy or angiography.

• Differentiation of primary and secondary vasculitis is essential because their pathophysiologic, prognostic, and therapeutic aspects differ.

• The diagnosis of vasculitis should be considered in any patient with febrile illness and organ ischemia without other explanation.

Epidemiology

In 1994, the Chapel Hill Consensus Conference named and defined the 10 most common forms of vasculitis according to vessel size (Box 110.1). This system is based on the fact that different forms of vasculitis attack different vessels.1,2 These criteria were established to differentiate specific types of vasculitis, but they are often used as diagnostic criteria. The vasculitic syndromes feature a great deal of heterogeneity and overlap, which leads to difficulty with regard to categorization.3 In addition, many patients display incomplete manifestations, thereby adding to the confusion. Emergency physicians should keep in mind the fact that nature does not always follow the patterns and artificial boundaries drawn by classification systems.4

Box 110.1

Chapel Hill Consensus Conference Classification of Primary Vasculitides

From Kallenberg CG. Vasculitis: clinical approach, pathophysiology, and treatment. Wien Klin Wochenschr 2000;112:656–9.

Takayasu Arteritis

Takayasu arteritis (also referred to as aortic arch syndrome) is a granulomatous large vessel vasculitis that primarily affects the aorta, its branches, and the pulmonary and coronary arteries.1 This rare disease predominantly affects women in the 20- to 30-year-old age group and is more common in Asian and South American women. Mortality ranges from 10% to 75%.

Polyarteritis Nodosa

Polyarteritis nodosa is a multisystem necrotizing vasculitis of small- and medium-sized muscular arteries. Visceral and renal artery involvement is characteristic.3 The mean age at onset is 50 years, although it can occur at any age. Men, women, and racial groups are all affected equally. This rare disease affects fewer than 10 per 1 million persons worldwide.

Kawasaki Disease

Kawasaki disease, also referred to as mucocutaneous lymph node syndrome, primarily affects children younger than 5 years. This acute systemic vasculitis is a febrile multisystem disease that is the leading cause of acquired heart disease in children in the United States.1 The disease occurs worldwide but predominates in Japan, Asia, and the United States.

Churg-Strauss Syndrome

Churg-Strauss syndrome is a rare small vessel vasculitis manifested by fever, asthma, and hypereosinophilia.1 This disease is also referred to as allergic angiitis and granulomatosis, particularly when it affects the lungs. It is estimated that about 3 million people are affected worldwide, with an equal incidence between sexes. It is seen at all ages with a mean onset at 44 years of age.

Henoch-Schönlein Purpura

Henoch-Schönlein purpura (anaphylactoid purpura) is a small vessel vasculitis that predominantly affects children and is characterized by palpable purpura, arthralgia, glomerulonephritis, and gastrointestinal symptoms.3 Though also seen in adults, 75% of cases occur in children younger than 8 years. It is more common than other vasculitides and affects males more frequently than females in a 2 : 1 ratio. It has a peak incidence in winter and spring and usually follows an upper respiratory tract infection.

Cutaneous Leukocytoclastic Vasculitis

This disorder, also called hypersensitivity vasculitis or predominantly cutaneous vasculitis, involves small vessels of the skin and is the most common vasculitic manifestation seen in clinical practice.1 It has an incidence of 15 per million.4 In about 70% of cases, cutaneous vasculitis occurs along with an underlying process such as infection, malignancy, medication exposure, and connective tissue disease or as a secondary manifestation of a primary systemic vasculitis.

Behçet Syndrome

Behçet syndrome is a multisystem inflammatory disease that affects vessels of all size.1 It is manifested as recurrent aphthous oral and genital ulcerations along with ocular involvement. Behçet syndrome is most prevalent at ages 20 to 35 years, with males suffering more severe disease.

Pathophysiology

Vasculitis, also known as the vasculitides or the vasculitis syndromes, is a clinicopathologic process that results in inflammation and damage to blood vessels.3 Cell infiltration with inflammatory modulators causes swelling and changes in function of the vessel walls. This compromises vessel patency and integrity and leads to tissue ischemia, necrosis, and bleeding. Because most forms of vasculitis are not restricted to a certain vessel type or organ, the syndromes are broad and heterogeneous. Vasculitis is a systemic multiorgan disease, so the findings may be dominated by a single or a few clinical organ manifestations.4

Management of patients with the secondary forms of vasculitis needs to be directed toward the underlying disease process. The primary vasculitides, once thought to be uncommon, have proved to be much less rare than previously estimated, and awareness of the incidence and prevalence of all forms of vasculitis has recently increased.5 This chapter focuses on the primary or de novo vasculitides.

The pathophysiology of the vasculitis syndromes remains poorly understood, with variation between disease states contributing to the difficulty. It is also not clear why vasculitis develops in certain patients in response to antigenic stimuli and not in others; however, in each disease state, immunologic mechanisms play an active role in mediating blood vessel inflammation.1 Blood vessels can be damaged by three potential mechanisms (Box 110.2).6

Box 110.2

Three Potential Mechanisms of Blood Vessel Damage in Vasculitis with Corresponding Diseases

From Fauci AS, Sneller MC. Pathogenesis of vasculitis syndromes. Med Clin North Am 1997;81:221–42.

Two main factors are involved in the expression of a vasculitic syndrome: genetic predisposition and regulatory mechanisms associated with the immune response to antigens. Only certain types of immune complexes cause vasculitis, and the process may be selective for only certain vessel types. Other factors are also involved—for example, the reticuloendothelial system’s ability to clear the immune complex, the size and properties of the complex, blood flow turbulence, intravascular hydrostatic pressure, and the preexisting integrity of the vessel endothelium.3

Temporal (Giant Cell) Arteritis

Giant cell arteritis is a panarteritis characterized by inflammatory mononuclear cell infiltrates and giant cell formation in vessel walls. The intima proliferates and the internal elastic lamina fragments. Organ pathology results from ischemia related to the involved vessel derangement.3

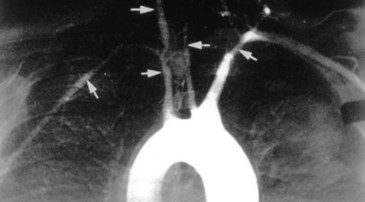

Takayasu Arteritis

The inflammation in Takayasu arteritis involves all vessel wall layers of medium- and large-sized vessels, especially the aorta and its branches. Panarteritis with inflammatory mononuclear cell infiltrates and giant cells predominates. This results in scarring and fibrosis with disruption and degeneration of the elastic lamina. Narrowing of the vessel lumen (Fig. 110.1) follows with frequent thrombosis.3 Vessel dilation and the formation of aneurysms may also occur. Organ pathology results from ischemia.

Polyarteritis Nodosa

The inflammatory lesions associated with polyarteritis nodosa are segmental and involve the bifurcations and branches of arteries. Polymorphonuclear neutrophils infiltrate all layers of the vessel wall. The resultant intimal proliferation and degeneration of the vessel wall lead to vascular necrosis, which in turn results in thrombosis, compromised blood flow, and infarction of the involved tissues and organs. Characteristic aneurysmal dilations of up to 1 cm are common. Multiple organ systems are involved.3

Kawasaki Disease

The etiology of Kawasaki disease is unknown, but increasing evidence supports an infectious cause; however, whether the inflammatory response results from a conventional antigen or a superantigen continues to be debated. Although a strong predilection for the coronary arteries is seen, this vasculitis is systemic and may involve medium-sized arteries with corresponding manifestations. Initially, neutrophils are present in great numbers, but the infiltrate rapidly switches to mononuclear cells, T lymphocytes, and immunoglobulin A (IgA)-producing plasma cells. Inflammation involves all three layers of vessels. As in other vasculitides, there is typical intimal proliferation and infiltration of the vessel wall with mononuclear cells, which leads to beadlike aneurysms and thrombosis. Cardiomegaly, pericarditis, myocarditis, myocardial ischemia, and infarction may result.3

Wegener Granulomatosis

The pathology of Wegener granulomatosis involves a necrotizing vasculitis of small vessels with granuloma formation. The typical necrotizing granulomatous vasculitis in the lungs commonly leads to scarring, atelectasis, and obstruction. The upper airways also become inflamed, with necrosis and granuloma formation. Renal involvement takes the form of a focal and segmental glomerulonephritis that may become rapidly progressive. Few or no immune complexes are found on biopsy; the involvement of immunopathology is unclear. c-ANCAs develop in a large number of these patients, but this correlation is not clear.3 Besides the typical sinus, lung, and kidney involvement, other organs may be affected because Wegener granulomatosis is a systemic small vessel vasculitis.

Churg-Strauss Syndrome

The characteristic histopathologic features of Churg-Strauss syndrome include tissue infiltration by eosinophils, necrotizing small vessel vasculitis, and extravascular “allergic” granulomas.1 The process can occur in any organ, but lung involvement predominates, and its association with asthma is strong. The combination of asthma, eosinophilia, granulomas, and vasculitis strongly suggests a hypersensitivity reaction as the triggering factor.3

Henoch-Schönlein Purpura

Henoch-Schönlein purpura is an immune complex disease characterized by deposition of IgA-containing complexes. Suggested but unproved inciting antigens include upper respiratory infections, foods, drugs, insect bites, and vaccinations.3 All aspects of the disease are more serious when an adult is affected.

Cutaneous Leukocytoclastic Vasculitis

The pathology predominantly involves small vessels, especially postcapillary venules. Acutely, neutrophils infiltrate the vessels, cause destruction, and result in nuclear debris—thus the term leukocytoclastic. As the process becomes more chronic, mononuclear cells and eosinophils become involved. Erythrocytes frequently extravasate and cause a classic palpable purpura, which is a hallmark of the disease.3

Presenting Signs and Symptoms

The diagnosis of many vasculitic syndromes is based more on the clinical findings than on laboratory results; therefore, a detailed history plus physical examination is an essential first step in the diagnosis.7 A high index of suspicion is necessary. The diagnosis should be considered in any patient with systemic febrile illness and signs of organ ischemia without a direct explanation. Nonspecific symptoms such as weight loss, night sweats, and malaise are common. The vessels involved may correlate with the specific symptoms displayed.8

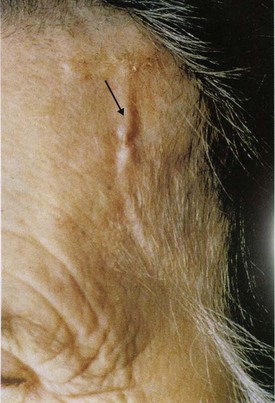

Temporal (Giant Cell) Arteritis

Patients with temporal arteritis have local symptoms related to the arteries involved. Headache, scalp tenderness associated with the inflamed temporal artery (Fig. 110.2), jaw claudication, and visual disturbances are typical. Symptoms associated with polymyalgia rheumatica are frequently displayed. Constitutional symptoms such as fever, malaise, fatigue, anorexia, weight loss, arthralgias, and night sweats are also common. The most serious complication is ocular involvement as a result of ischemic optic neuropathy, which may lead to blindness; however, loss of vision is usually avoided with proper treatment. A later complication may be an aortic aneurysm.9–11

Takayasu Arteritis

Patients with Takayasu arteritis have ischemic symptoms of the involved vessels; such symptoms include visual problems, faint or absent pulses in the upper extremities, and myocardial, abdominal, and lower extremity ischemia. Differences in extremity blood pressure and bruits may also be present. Up to 40% of patients may experience systemic symptoms such as fever, malaise, night sweats, arthralgias, myalgias, weight loss, and anorexia. Death usually occurs from congestive heart failure or stoke. The course may be progressive and unremitting and become fulminant or may stabilize into remission.3

Polyarteritis Nodosa

The most common symptoms of polyarteritis nodosa are fever, hypertension, myalgias, arthralgias, weight loss, malaise, and headache. Renal involvement evolves as flank pain, hematuria, renovascular hypertension, and renal failure. Skin lesions range from subcutaneous nodules to distal ischemia. Gastrointestinal manifestations include pain, malabsorption, bleeding, and perforation. Congestive heart failure secondary to coronary artery vasculitis may occur. A classic symptom is orchitis, which may occur in one third of male patients.4

Kawasaki Disease

The characteristic clinical features of Kawasaki disease are fever for at least 5 days, conjunctivitis, changes in the oral mucosa, a generalized rash, red palms and soles, indurative edema with subsequent skin desquamation, and cervical lymphadenopathy.4 The presence of five of these symptoms confirms the diagnosis. Of course, atypical cases with fewer symptoms occur.

Wegener Granulomatosis

The characteristic manifestation of Wegener granulomatosis involves symptoms in the upper or lower airways (or both) for a prolonged period before the disease becomes systemic. Up to 90% of patients have sought medical attention for sinus or pulmonary problems earlier.1 Upper respiratory symptoms include pain, purulent or bloody drainage, ulcerations, hoarseness, stridor, and deafness. Pulmonary findings are manifested as cough, dyspnea, chest pain, and hemoptysis, which may become severe. Pulmonary nodules, infiltrates, or cavitations may be seen on chest radiographs. Hypoxemia ensues when the lungs become affected.

Other manifestations include ocular inflammation ranging from conjunctivitis, episcleritis, and scleritis to retinal vasculitis and retroorbital masses. Skin lesions may appear as ulcerations, subcutaneous nodules, or purpura with necrosis. Central nervous system symptoms stem from infarction, cranial nerve neuropathy, and mononeuritis multiplex. Bowel perforation and bleeding may be symptoms of gastrointestinal involvement; pericarditis, coronary ischemia, and cardiomegaly may signal cardiac involvement.3 Vague symptoms such as malaise, weakness, arthralgia, fever, and anorexia are common.

Churg-Strauss Syndrome

The disease is best known for its severe and frequent exacerbations of asthma and relapsing vasculitis.1 The asthma associated with Churg-Strauss syndrome is not a classic allergic asthma that begins early in life; rather, it begins later in life around 35 years of age. It is severe, and patients frequently become steroid dependent.4

Henoch-Schönlein Purpura

The classic clinical picture of Henoch-Schönlein purpura includes four cardinal manifestations—palpable purpura, arthralgias, gastrointestinal involvement, and glomerulonephritis. The palpable purpura develops in nearly all cases and occurs most commonly over the buttocks and legs (Fig. 110.3). Polyarthralgia also develops in most patients. Gastrointestinal symptoms include abdominal pain with nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, constipation, and occasional gastrointestinal bleeding.

Fig. 110.3 Palpable purpura in a patient with Henoch-Schönlein purpura.

(From Hoffman R, Benz Jr EJ, Shatttil SJ, et al, editors. Hematology: basic principles and practice. 4th ed. Philadelphia: Saunders; 2005.)

Renal disease is characterized by a mild glomerulonephritis with hematuria and proteinuria. Glomerulonephritis is seen in 20% to 50% of patients, with 2% to 5% progressing to end-stage renal disease.1

Cutaneous Leukocytoclastic Vasculitis

Clinically, besides purpura, patients may exhibit macules, papules, vesicles, bullae, subcutaneous nodules, or urticaria. The skin usually becomes pruritic and painful, and the lesions may progress to ulcers. Although the skin is predominantly involved, patients may exhibit systemic symptoms such as myalgias, fever, anorexia, and malaise.3 The course of the disease ranges from a brief single episode to multiple prolonged recurrences with infrequent progression to systemic vasculitis.

Behçet Syndrome

Patients with Behçet syndrome have painful ulcers that occur as one ulcer or multiple ulcers; the ulcers last for 1 to 2 weeks and resolve without scarring. Besides oral ulcers, patients with Behçet syndrome may exhibit two or more of the following signs or symptoms: recurrent genital ulcers, skin lesions, eye lesions, and a positive pathergy test.1

Other symptoms include mild arthritis of the lower extremity joints, gastrointestinal inflammation, and ulcerations. Central nervous system manifestations include meningoencephalitis, benign intracranial hypertension, multiple sclerosis–like symptoms, and psychiatric disturbances. Large venous or arterial thrombi or occlusions occur in 25% to 38% of patients.1,3 Pulmonary emboli are possible.

Differential Diagnosis and Medical Decision Making

Biopsy and Angiography

Angiography is an excellent diagnostic modality when medium and large vessels are involved and visceral organ involvement is likely. This modality is the “gold standard” in the work-up of Takayasu arteritis, for which a full evaluation of the aorta is recommended. Angiography demonstrates luminal patency but provides no information about cellular or tissue status. Early vessel inflammation may still be present in a fully patent vessel. Conversely, vessel narrowing may also be due to fibrosis, not active disease.8 Therefore, clinical correlation is advised with each angiographic finding.

Noninvasive Imaging

Single-photon emission computed tomography (SPECT) uses multiplanar nuclear imaging to investigate abnormalities in perfusion, especially when evaluating central nervous system vasculitis. Clinical correlation is necessary because perfusion defects may not distinguish vasculitis from entities such as vasospasm, thromboembolism, atherosclerosis, and malignant hypertension. SPECT may also be useful in evaluating the coronary arteries in patients with Kawasaki disease.8

Diagnosis of Specific Vasculitic Syndromes

Takayasu Arteritis

Laboratory findings during active disease include an elevated ESR and increased CRP levels.4 Angiography demonstrates stenosis, occlusion, dilation, and aneurysms of the aorta and its branches. The entire aorta should be visualized to fully appreciate the spectrum of this disease.3 Spiral CT angiography and MRA have been shown to be useful.

Wegener Granulomatosis

The diagnosis is made by biopsy demonstrating necrotizing granulomatous vasculitis with an aggregation of neutrophils in nonrenal tissue. Renal biopsy reveals focal, segmental, necrotizing, crescentic glomerulonephritis.4 Biopsy findings coincide with the characteristic clinical findings of sinus, pulmonary, and renal symptoms. Although the use of ANCA testing is only adjunctive, its specificity is 90% for Wegener granulomatosis if active glomerulonephritis is present.

Henoch-Schönlein Purpura

Laboratory studies are nonspecific and may reveal a mild leukocytosis and occasional eosinophilia. Serum IgA levels are elevated in 50% of patients.3 The diagnosis remains a clinical diagnosis based on the characteristic findings. A skin biopsy is occasionally necessary for confirmation and reveals leukocytoclastic vasculitis with IgA immune deposition. Renal biopsy better serves as a prognostic indicator.1

Cutaneous Leukocytoclastic Vasculitis

Laboratory values are usually within normal limits, including ESR and CRP levels. Mild leukocytosis and eosinophilia may be present. Laboratory studies should be used primarily to rule out the presence of systemic vasculitis. Minimal to no signs of inflammation should be found.4 The diagnosis is made by skin biopsy and by carefully ruling out systemic disease or exogenous reasons for the vasculitis.

The clinical and histopathologic appearance of the lesions is indistinguishable from the cutaneous manifestations of the systemic vasculitides; therefore, the diagnosis should be one of exclusion after other causes have been ruled out.2 Only then can the disorder be called true cutaneous leukocytoclastic vasculitis or idiopathic cutaneous vasculitis.

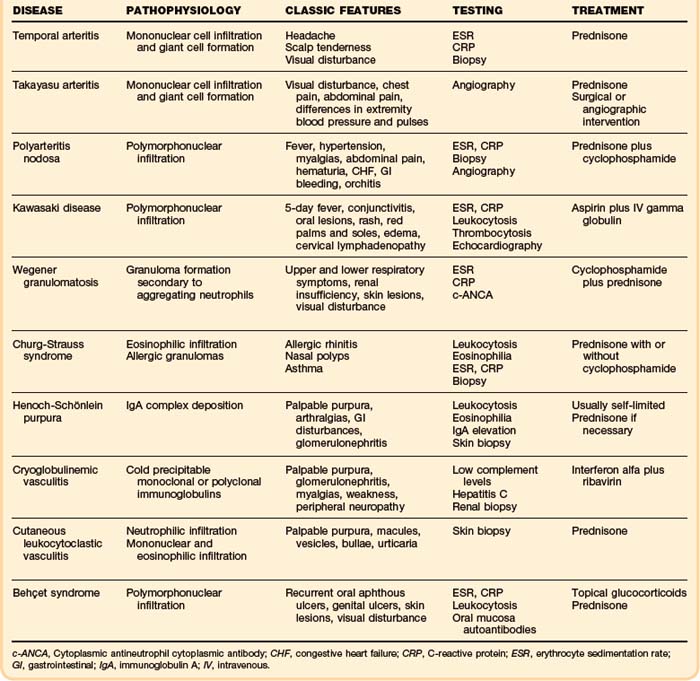

Treatment

The combination of clinical, laboratory, biopsy, and radiographic findings usually points to a specific syndrome (Table 110.1). Therapy should then be initiated as appropriate. If the vasculitis is associated with a specific disease such as neoplasm, infection, or connective tissue disease, the underlying disease should be treated. If the syndrome resolves, no further treatment is needed. If the syndrome persists, treatment of vasculitis should be initiated. Likewise, if an offending antigen is recognized, it should be removed if possible. No further treatment is needed if the syndrome resolves; however, if the syndrome continues, treatment must be initiated. Treatment initiated for a primary vasculitis syndrome should focus on using the most effective and least toxic options based on published experience.12

Temporal (Giant Cell) Arteritis

Treatment should commence immediately and not be delayed by diagnostic procedures. Administration of 40 to 60 mg of prednisone daily for 1 month is followed by a taper to 7.5 to 10 mg daily. This should be continued for 1 to 2 years to prevent relapse. Aspirin, 81 mg daily, has been shown to reduce cranial ischemic complications and should be given to patients without contraindications.13 Clinical symptoms and the ESR are used to monitor disease activity.

Takayasu Arteritis

Treatment consists of the combination of 40 to 60 mg/day of prednisone and aggressive surgical or angiographic procedures directed toward stenotic vessels. This approach corrects hypertension caused by renal artery stenosis, improves blood flow in ischemic vessels, and decreases risk for stroke,3 thereby resulting in decreased morbidity and improved survival.

Wegener Granulomatosis

Administration of cyclophosphamide (2 mg/kg/day) combined with prednisone (1 mg/kg/day) has proved to be the most successful therapy. Reported results are complete remission in 75%, a survival rate of 80%, and marked improvement in 91%.1 Though very effective, cyclophosphamide may be associated with severe bone marrow toxicity. Leukocytes must be monitored closely and kept at a level above 3000 mcg.

Full-dose cyclophosphamide therapy should be continued for 1 year after remission and then tapered off. Prednisone therapy may be changed to alternate-day administration after 1 month and then tapered off by 6 months.3 Methotrexate has shown some success in patients who cannot tolerate cyclophosphamide.

Churg-Strauss Syndrome

The most effective therapy is prednisone (1 mg/kg/day). The vasculitis usually remits more readily than the asthma, which may remain moderate to severe and thus make discontinuation of prednisone therapy difficult.1 Cyclophosphamide at 2 mg/kg/day may be added to the prednisone in patients not responsive to prednisone alone.

Henoch-Schönlein Purpura

However, when required, prednisone at 1 mg/kg/day is effective in lessening tissue edema, arthralgias, and abdominal pain. The dose should be tapered as the symptoms abate. Glucocorticoids have no proven benefit on skin and renal involvement and have not been shown to shorten the course of the disease or prevent relapse.3

Cutaneous Leukocytoclastic Vasculitis

If an underlying process is discovered to be the cause of the cutaneous symptoms, treatment should be aimed at the underlying process. If an exogenous agent is the culprit, removal of it usually results in remission of the skin process. If true cutaneous leukocytoclastic vasculitis is determined to be the etiology, glucocorticoids administered at a dosage of 1 mg/kg/day have proved effective.3

Behçet Syndrome

Treatment is based on disease manifestations. Oral and skin lesions respond well to topical glucocorticoids, dapsone, or colchicine. Thrombophlebitis is treated with aspirin. Ocular and central nervous system manifestations require aggressive treatment with immunosuppressive agents such as glucocorticoids, azathioprine, or cyclosporine.1

Follow-Up, Next Steps in Care, and Patient Education

Polyarteritis Nodosa

Discharge home with follow-up is appropriate except in patients with evidence of end-organ failure.

Kawasaki Disease

Except for rare fatal cardiac complications, the prognosis is good, typically with full recovery.3 Children in whom aneurysms develop require close follow-up after discharge, and some patients with severe disease may need long-term anticoagulation.

Wegener Granulomatosis

Outpatient management is appropriate except in patients with advanced end-organ involvement. On achievement of remission, long-term follow-up is essential. Up to 50% of patients have one or more relapses. With close follow-up and immediate reinstitution of therapy, induction of remission is almost always a success. In many patients, especially those with multiple relapses, some degree of long-term morbidity develops, such as renal insufficiency, tracheal stenosis, hearing loss, or sinus impairment.3 Aggressive prompt therapy during the initial manifestation of the disease, as well as during relapses, helps diminish the degree of chronic morbidity.

Churg-Strauss Syndrome

Outpatient management is appropriate except in patients with advanced end-organ involvement. The prognosis of untreated patients is a 25% 5-year survival rate, which improves to 50% with proper treatment.1

Behçet Syndrome

Tips and Tricks

Although antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies (ANCAs) are quite common in patients with vasculitis, their role is not clear. ANCA testing may actually confuse the diagnostic picture when results are negative in a patient with clinical vasculitis, when there is a lack of quantitative correlation with disease activity, and when high titers are found in patients whose disease has fallen into remission.

Vision loss associated with temporal arteritis may be prevented with immediate and proper treatment. In patients with any signs of this complication, treatment must not be delayed because permanent vision loss may ensue.

Patients with Wegener granulomatosis often have prolonged signs and symptoms of upper or lower airway dysfunction, or both. Ninety percent of these patients have previously been evaluated for sinus problems that became chronic. A high index of suspicion is required.

The asthma associated with Churg-Strauss syndrome is a severe condition that usually begins when the patient is about 35 years of age. With treatment, the vasculitis commonly subsides much more readily than the asthma.

1 Langford CA, Fauci AS. The vasculitis syndromes. In: Kasper DL, Braunwald E, Fauci AS, et al, editors. Harrison’s principles of internal medicine, 17th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2008.

2 Stegeman CA, Kallenberg CG. Clinical aspects of primary vasculitis. Springer Semin Immunopathol. 2001;23:231–251.

3 Luqmani RA, Robinson H. Introduction to, and classification of, the systemic vasculitides. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2001;15:187–202.

4 Langford CA. Vasculitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2003;111(2 Suppl):S602–S612.

5 Savage OS. The evolving pathogenesis of systemic vasculitis. Clin Med. 2002;2:458–464.

6 Kallenberg CG. Vasculitis: clinical approach, pathophysiology and treatment. Wien Klin Wochenschr. 2000;112:656–659.

7 Fauci AS, Sneller MC. Pathogenesis of vasculitis syndromes. Med Clin North Am. 1997;81:221–242.

8 McLaren JS, McRorie ER, Luqmani RA. Diagnosis and assessment of systemic vasculitis. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2002;20:854–862.

9 Langford CA. Management of systemic vasculitis. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2001;15:281–297.

10 Seo P, Stone JH. Large-vessel vasculitis. Arthritis Rheum. 2004;51:128–139.

11 Younger DS. Headaches and vasculitis. Neurol Clin. 2004;22:207–228.

12 Mohan N, Kerr GS. Diagnosis of vasculitis. Best Res Pract. Clin Rheumatol. 2001;15:203–223.

13 Langford CA. Vasculitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2010;125:S216–S225.