28 Vasculitis

Etiology and Pathogenesis

Classification

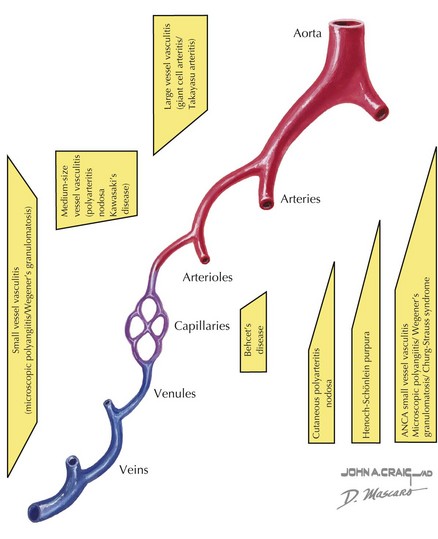

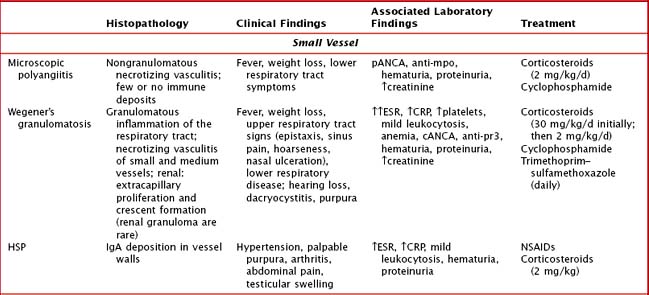

Vasculitis can be classified based on the involvement of primarily large, medium, or small vessels (Figure 28-1). In addition, certain vasculitides have a predilection for arteries, veins, or both. The vasculitides can be further classified as granulomatous or nongranulomatous. The granulomatous diseases include Takayasu arteritis, Wegener’s granulomatosis, and Churg-Strauss syndrome (see Chapter 30). The nongranulomatous vasculitides include PAN, KD, microscopic polyangiitis, HSP, cutaneous leukocytoclastic vasculitis, and essential cryoglobulinemic vasculitis.

Clinical Presentation

Certain patterns of clinical symptoms and organ involvement may be suggestive of a specific vasculitis (Box 28-1). For example, whereas palpable purpura, arthralgias, abdominal pain, and renal disease suggest HSP, persistent fever, conjunctivitis, cervical lymphadenopathy, extremity swelling, mucocutaneous changes, and rash suggest KD (see below). Microscopic polyangiitis is associated with high titers of pANCA (protoplasmic-staining antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies) and affects mainly the pulmonary and renal systems. Hypersensitivity vasculitis is a necrotizing vasculitis that presents with a papular rash that may be red or blistering and is often associated with infection or medication exposure. Hypocomplementemic urticarial vasculitis presents with urticarial skin lesions and low serum complement levels of C4 and C3. Behçet’s disease is a unique systemic vasculitis that affects both arteries and veins. The classic triad of Behçet’s disease includes oral ulcers, uveitis, and genital ulcers; however, any organ system can be affected.

PAN is a necrotizing vasculitis affecting the medium-sized arteries and can present with systemic disease or in a limited form that only involves the skin and joints. It occurs in school-aged children, and there is typically a history of a preceding upper respiratory infection or streptococcal pharyngitis. In unvaccinated children, hepatitis B can be causative. Symptoms include prolonged fevers, malaise, calf pain, testicular pain, and weight loss. Physical examination findings include painful nodules (particularly on the feet), livedo reticularis (see Figure 29-2), myalgias, and arthritis of large joints. In the systemic form, any organ system can be affected; thus, hypertension, renal abnormalities, gastrointestinal involvement, and coronary disease can be seen. Of the large vessel diseases, temporal arteritis is not seen in childhood. Takayasu arteritis, the third most common childhood vasculitis, preferentially affects the large branches of the aorta. Examination may reveal bruits, hypertension, and absent pulses.

Evaluation and Management

Management

Management depends on the specific type of vasculitis and should be done in consultation with a rheumatologist (Table 28-1). Corticosteroids are the cornerstone of treatment for almost all of the vasculitides. In addition, depending on severity of disease, use of immunosuppressive agents such as methotrexate, azathioprine, cyclosporine, and cyclophosphamide may be warranted. In immune complex–mediated disease, plasmapheresis may have a role.

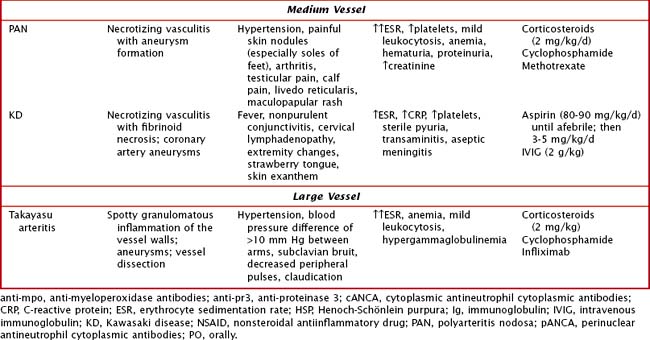

Henoch Schönlein Purpura

HSP is the most common vasculitis in childhood (Figure 28-2). It is a leukocytoclastic vasculitis (leukocytes infiltrate the vessel walls and cause necrosis) predominantly affecting the small blood vessels. The classic triad is described as nonthrombocytopenic palpable purpura, arthritis, and abdominal pain. The most feared long-term morbidity of HSP is chronic renal disease. It affects boys more often than girls and most cases occur in winter and spring. Although HSP can affect adults, the peak age of onset is between 3 and 15 years.

There are proposed classification criteria to guide the diagnosis of pediatric HSP (Box 28-1). The purpuric rash has raised, nontender, nonpruritic, deep red to purple lesions that are most often found in dependent areas such as the buttocks and lower extremities (with most crops at the feet and ankle area). However, they can also be on the face, trunk, and upper extremities. Abdominal pain occurs in approximately two-thirds of patients. More severe gastrointestinal symptoms include gastrointestinal hemorrhage and intussusception. Rare gastrointestinal complications include pancreatitis and ulcerative colitis. Up to 25% of children may have abdominal symptoms of HSP before the onset of rash, making the diagnosis a challenge. Arthritis affects 50% to 80% of children with HSP. It usually affects large joints, such as the knee or ankle, but small joints can also be involved. It is often painful but not usually erosive. Fortunately, the arthritis of HSP is usually transient, lasting a few days to 1 week. Renal manifestations are seen in about one-third of patients with HSP. Symptoms range from microscopic hematuria or proteinuria to acute renal failure. Of the children who develop renal involvement, most do so within the first 3 months of disease.

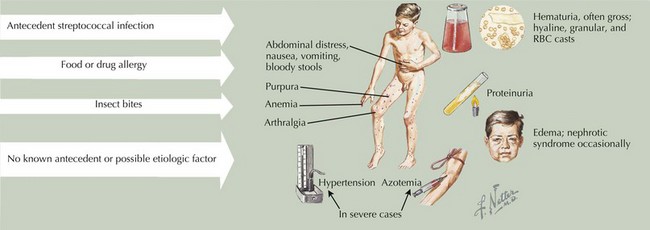

Kawasaki Disease

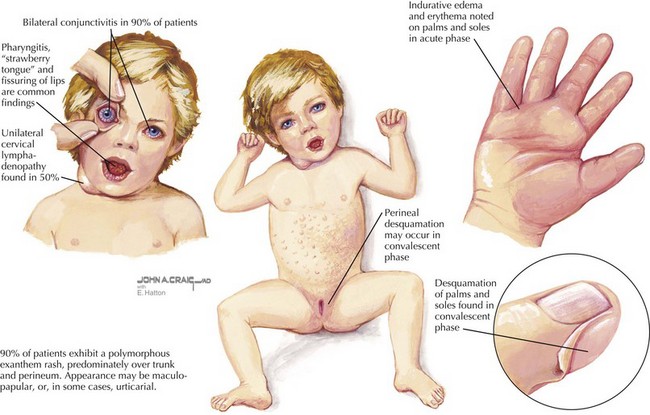

KD is the second most common vasculitis seen in children (Figure 28-3). It is considered an acute vasculitis of medium-sized arteries. The peak age of onset is 2 years old, with 80% to 90% of cases occurring in children younger than 5 years old. Unlike most vasculitides, it is more common in boys than girls (about 1.5 : 1), and it has a higher incidence in the Japanese and Korean populations. Although the cause of KD is unknown, studies have suggested a transmissible agent causing a dysfunctional immune response; however, a specific agent has yet to be discovered.

Diagnosis is based on clinical criteria (Table 28-2). The fever, which is usually greater than 38.5°C, must be present for more than 5 days. It is typically minimally responsive to antipyretic medications. The conjunctivitis is nonexudative and limbic sparing. In some cases, patients can develop anterior uveitis, so a slit-lamp examination may be helpful if the diagnosis is unclear. Oral mucous membrane changes occur with continued inflammation and may include dry, red, cracked lips, a “strawberry” tongue; and pharyngitis. Swelling or erythema of the hands and feet usually occurs late in the acute phase. During the convalescent phase, desquamation of the tips of the toes and fingers may be noticeable. A transient arthritis is noted in about one-third of patients and can involve large or small joints. The rash of KD is nonspecific and ranges from erythema at the perineal area or a morbilliform exanthem on the trunk or extremities. Vesicular or pustular lesions are not typical. The final criterion is lymphadenopathy, which is usually the least common finding of KD.

| Fever greater than or equal to 5 days duration with at least four of the following clinical signs | |

|---|---|

| Sign | Children with Kawasaki Disease (%) |

| 1. Bilateral conjunctival injection with limbic sparing | 80-90 |

| 2. Oral mucosal membrane changes (e.g., injected or fissured lips, strawberry tongue, injected pharynx) | 80-90 |

| 3. Peripheral extremity changes (e.g., erythema or edema of hands and feet in the acute phase or desquamation in the convalescent phase) | 80 |

| 4. Polymorphous, nonvesicular exanthema, usually on the trunk | >90 |

| 5. Cervical lymphadenopathy with anterior cervical lymph node ≥1.5 cm in diameter | 50 |

Cabral D, Morishita K. Approach to evaluating childhood vasculitis. UpToDate. November 12, 2008.

Dedeoglu F, Sundel RP. Vasculitis in children. Rheum Dis Clin North Am. 2007;33:555-583.

Ozen S, Ruperto N, Dillon MJ, et al. EULAR/PreS endorsed consensus criteria for the classification of childhood vasculitides. Ann Rheum Dis. 2006;65:936-941.

Woo P, Laxer RM, Sherry DD. Vasculitis. In Pediatric Rheumatology in Clinical Practice, ed 1. London: Springer-Verlag; 2007. pp 97-117