CHAPTER 112 Vascular Imaging of Renal and Pancreatic Transplantation

The use of kidney transplantation to treat end-stage renal disease in the United States has steadily increased from 43/million in 1996 to 55.5/million in 2005. The most recent data (2006) show that there are now more than 103,000 Americans living with a renal transplant and more than 9,400 with a pancreas or kidney-pancreas transplant, up from 55,000 and 4,000, respectively, in 1996.1 Imaging plays a major role in the surveillance of transplant complications. In this chapter, the vascular complications associated with renal and pancreatic transplantation are discussed.

VASCULAR EVALUATION OF RENAL TRANSPLANT RECIPIENTS

Transplant Renal Artery Stenosis

Prevalence and Epidemiology

TRAS has been reported in 1% to 23% of cases, with most series finding 2% to 10% of renal transplants are complicated by TRAS.2,3 It is usually a relatively late complication, occurring from 3 months to 2 years or more after transplantation.

Etiology and Pathophysiology

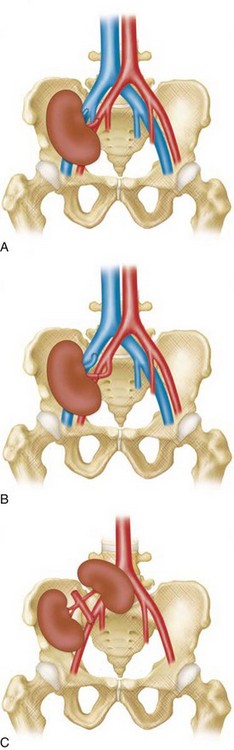

TRAS is most common at the anastomosis or most proximal segment of the donor artery and the risk is directly related to technique. Cadaveric transplants are typically harvested with an aortic patch from which the single or multiple renal arteries arise. The patch can then be anastomosed with its arterial origins end to side on the external iliac artery. Grafts from living donors, who cannot sacrifice an aortic patch, are typically anastomosed end to end to the internal iliac artery. When living donor grafts with multiple renal arteries must be used, the accessory arteries may be reconstructed to flow from the main renal artery, anastomosed separately, or anastomosed to the inferior epigastric artery (Fig. 112-1). End-to-end anastomoses have a threefold greater risk of stenosis.

Contributing causes of stenosis in end to end anastomoses are thought to be abnormal fluid dynamics and abrupt changes in caliber. Other more general causes or precipitants of stenosis include faulty suture technique, clamp injury, and kinking of the artery. In addition, atherosclerosis can occur or progress in the donor artery. An association with stenosis has also been shown among patients who have experienced episodes of acute rejection possibly caused by a component of endothelial injury from rejection of the graft artery. An additional association with cytomegalovirus infection has been reported.4 Finally, a stenosis of the recipient artery, usually the external iliac or common iliac artery, proximal to the anastomosis may have hemodynamic effects on the kidney, similar to stenosis of the graft artery.

Manifestations of Disease

Imaging Techniques and Findings

Ultrasound

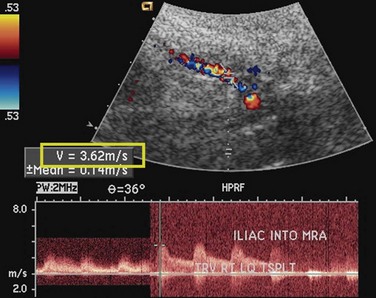

Like native renal artery stenosis, the diagnosis of TRAS is made with ultrasound by demonstrating a focal area of aliasing on color Doppler imaging from turbulence caused by the stenosis and an elevated peak systolic velocity through the stenosis more than 2.5 m/sec on spectral Doppler imaging (Fig. 112-2).5 Because of the proximity of the allograft to the body wall in the anterior pelvis, the main artery can often be visualized in its entirety, aiding the chances of confirming the diagnosis. Power Doppler, with its high sensitivity to flow in all directions, is helpful to localize and map the artery for further evaluation with color Doppler and placement of the spectral Doppler gate. However, transplant arteries are typically much more tortuous than native renal arteries. This makes the setting of accurate angle correction on spectral Doppler more difficult and sometimes almost impossible. Furthermore, a range of elevated velocities has been shown in transplant arteries, even when stenosis is not suspected or proven not to be present, particularly if there is tortuosity.6 When there is no significant curvature, an elevated velocity may reflect elevated velocity in the external iliac artery. In these cases, a ratio of velocities in the main transplant artery and external iliac artery less than 1.8 is unlikely to be stenosis.

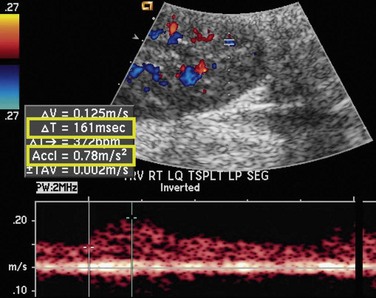

As in native renal stenosis, the characteristic parvus-tardus waveform of the intrarenal arteries downstream from a stenosis can support the diagnosis. This is reflected in spectral broadening of the arterial waveform, retarded acceleration less than 1.5 m/sec2, and increased acceleration time more than 0.08 to 0.10 second (Fig. 112-3) However, these findings have been shown to be less specific than peak systolic velocity and should be used to support the diagnosis based on peak systolic velocity.7 Resistive and pulsatility indices can also be lowered in TRAS but are only nonspecific indicators of graft dysfunction.

Magnetic Resonance Imaging

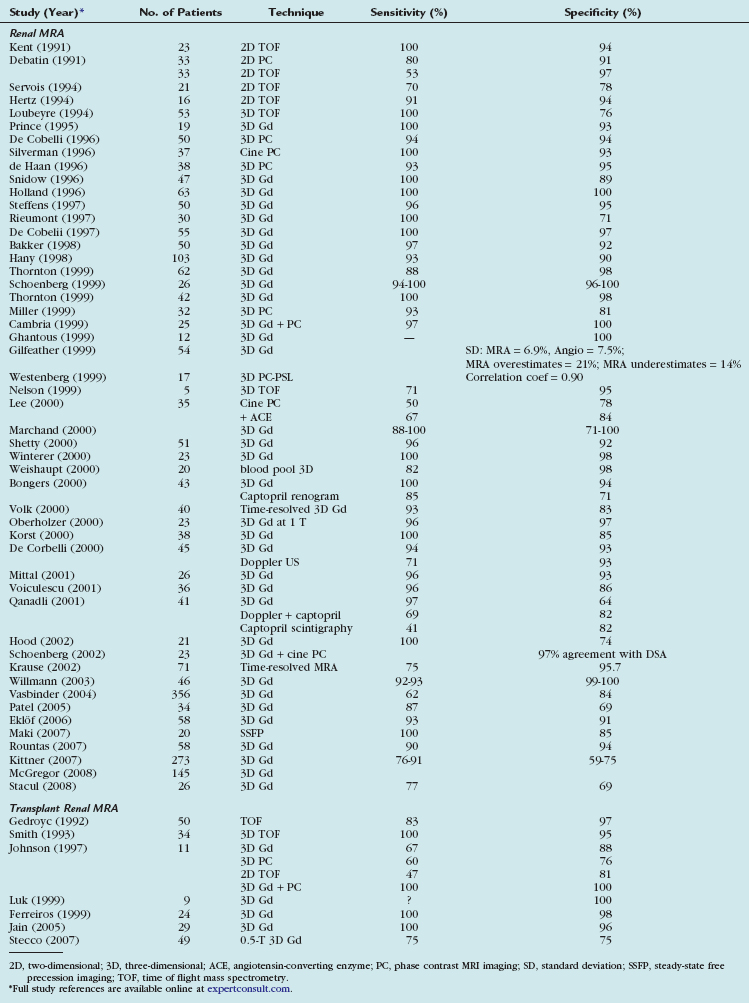

MRI can demonstrate TRAS with a high degree of accuracy. In multiple series, gadolinium (Gd)-enhanced three-dimensional MRA has been shown to have a sensitivity of 67% to100% and a specificity of 75% to 100% for hemodynamically significant stenosis (Table 112-1). Although technically challenging on older scanners, the examinations have become routine with state of the art 1.5-T scanners.

Review of source images, as well as review of three-dimensional postprocessed projectional views, is necessary to make the appropriate diagnosis. MIPs and multiplanar reformations using variable thicknesses allow for direct visualization through the lumen of the transplant renal artery, the anastomosis, the iliac arteries, and usually the first-order branch arteries (Fig. 112-4). It is the ability to manipulate the volumetric data of MRA that makes it so effective. This is especially true in tortuous vessels, which are typical in renal transplants. Shaded surface volume renderings can be especially helpful to visualize the anatomy in the case of tortuous vessels.

An effective complement to Gd-enhanced MRA is three-dimensional phase contrast MRA. This sequence achieves the MR signal, and therefore contrast, from protons moving across flow-encoding gradients. The signal is velocity-encoded at a certain upper threshold so that superfast flow at severe stenoses nulls the signal. Although the sequence acquisition time is long (typically 5 to 8 minutes), phase contrast MRA can be performed on a small field of view, either in the area of the transplant renal artery or any area of suspicion during imaging. Confirming suspected stenoses by demonstrating loss of signal on phase contrast helps eliminate false-positives. The combination of Gd-enhanced MRA and phase contrast MRA has been shown to increase specificity from 88% to 100%.8

The limit of MRA resolution for stenosis is typically at the level of the segmental first-order branch vessels. DSA is superior in its ability to detect segmental artery stenosis. Furthermore, intrarenal arteries are typically obscured by enhancement of the renal parenchyma with MRA. However, because MRA is an anatomic image that directly displays the vessels, similar to digital subtraction angiography (DSA), it offers many advantages over the detection of secondary findings of TRAS with Doppler ultrasound (US). For example, kinked or tortuous arteries that are technically challenging or impossible with Doppler US can be evaluated with the volumetric data sets of MRA. Iliac artery stenosis proximal to the transplant artery anastomosis is an uncommon cause of TRAS (pseudo-TRAS) that is much more easily identified with MRA (Fig. 112-5). Because of the shortage of grafts, en bloc transplantation of two kidneys of limited function such as from the cadavers of older patients or two small kidneys from pediatric cadavers, has gained acceptance (see Fig. 112-1C). In these cases, not only is the anatomy more complicated, but secondary findings of velocity or ratios of velocities have not been proven to be reliable indicators of TRAS. Direct anatomic imaging also allows for the detection of other pathologies that may be the cause of patient symptoms, such as infarctions, artery or vein thrombosis, urinary collecting system complications, or a perinephric collection. It can also be helpful for preoperative planning, even when DSA is already indicated.

Nuclear Medicine and Positron Emission Tomography

Although a decline in renal function after the administration of an ACE inhibitor can indicate TRAS, an ACE inhibitor challenge during scintigraphy is relatively contraindicated because of reports of ACE inhibitor–induced acute renal failure, in some cases irreversible. Additionally, the specificity is less than in US, MRA, and DSA.9

Treatment Options

Surgical and Interventional Management

The treatment of choice is percutaneous transluminal angioplasty (PTA), with stenting reserved for PTA failures. A postangioplasty pressure measurement is used to document successful repair of a stenosis. Placement of a metallic stent after angioplasty reduces the risk of restenosis.10 In one retrospective study, 94% of PTAs were technically successful and 82% were clinically successful, with a significant reduction in mean diastolic pressure and significant improvement in renal function.11

Arteriovenous Fistula and Pseudoaneurysm

Prevalence and Epidemiology

AVFs are common, occurring in approximately 17% of biopsies in a prospective trial. Of these, 50% will spontaneously occlude within 48 hours and another 25% within 4 weeks.12 The remaining 25% may persist for at least 1 year and often longer. Postbiopsy PSAs have an incidence of approximately 5% and are found in the vicinity of AVFs in most cases.

Etiology and Pathophysiology

Although no large trial has been undertaken, the risks for the development of AVFs and PSAs are thought to be hypertension, renal medullary disease, multiple needle passes, and deep or central biopsies.13 Deep or central biopsies (i.e., more than 1 to 2 cm from the surface of the kidney), are probably more likely to injure larger vessels, leading to larger, higher flow AVFs, which are more likely to be clinically significant.

Manifestations of Disease

Imaging Technique and Findings

Ultrasound

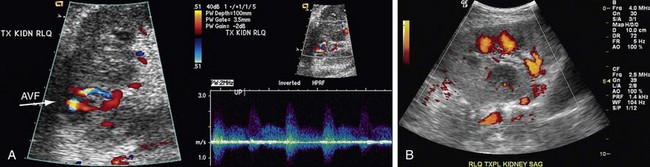

Color-flow Doppler and point spectral Doppler imaging are the mainstays of diagnosing AVF and PSA with ultrasound. Although real-time ultrasound may show an anechoic focus corresponding to an enlarged vein or a PSA sac, this is usually only the case with large or extrarenal lesions. The most common finding is a focal area of increased color saturation caused by tissue vibration around the AVF.14 Once this area has been localized, spectral Doppler investigation of the feeding artery usually shows increased velocity, with increased diastolic flow and spectral broadening (Fig. 112-6). The draining vein almost always shows increased pulsatility because of arterialization, but this finding by itself can be seen in other problems, such as right heart failure. The arterial and venous spectral findings should be compared with branch vessels in other segments of the transplant kidney to increase specificity. PSAs appear as an area of swirling, turbulent flow on color Doppler. There is biphasic to and fro flow through the neck of the cavity on spectral Doppler.

Magnetic Resonance Angiography

Contrast-enhanced three-dimensional MRA can demonstrate an AVF or PSA anatomically. The hallmark of an AVF is an early draining vein on the arterial phase of imaging. With the use and manipulation of MIPs, the actual fistulous connection can often be visualized. Similarly, a PSA can be demonstrated, including the size and dimensions of the neck and any thrombosed portions of the lesion (Fig. 112-7). Time-resolved three-dimensional MRA provides multiple sequential data sets that can provide visualization of early arterial filling of these vascular lesions.

Treatment Options

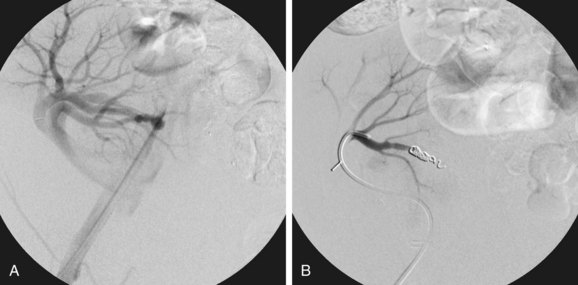

Most AVFs and PSAs spontaneously resolve or are of no clinical consequence. In the subset requiring therapy, AVFs and PSAs are usually treated with microcoil embolization after superselective catheter placement to allow for maximal sparing of the renal parenchyma (Fig. 112-8). Treatment with coil embolization has been recommended if bleeding, hematuria, or continued enlargement persists after 72 hours, if an AVF has not resolved after 30 days to prevent loss of transplant function, or if there are significant cardiovascular effects.

In a retrospective study of short- and long-term outcomes, technical relief (imaging findings of PSA or AVF) and symptomatic relief were achieved in 12 of 12 patients with superselective coil embolization.13 Estimated loss of renal parenchyma was less than 10% for nine patients and less than 20% for three patients. Chronic ischemia caused by AVF, leading to loss of most function, is treated with transplant nephrectomy.

Transplant Renal Artery and Vein Thrombosis

Primary renal artery or venous thrombosis is a known complication of transplantation. Thrombosis usually results in graft loss, except in rare cases when it is treated with timely emergent thrombectomy.15

Prevalence and Epidemiology

Renal graft thrombosis is usually seen in the postoperative period, occurring within 2 days in 62% of cases and within 10 days in 90% of cases in a survey of 134 consecutive cases.16 The overall incidence is 0.2% to 3.5% for arterial thrombosis and 0.3% to 3% for venous thrombosis.17

Manifestations of Disease

Imaging Indications and Algorithm

Cases of suspected graft thrombosis are usually first evaluated with ultrasound, which can be done rapidly, often in the recovery area. MRI with MRA is more sensitive and specific for differentiating graft thrombosis from rejection. It is essential to avoid delays in treatment. But there are cases of successfully treated thrombosis after the diagnosis was made on MRI following a nondiagnostic ultrasound.15

Vascular Evaluation of Living Renal Donors

Prevalence and Epidemiology

The overall prevalence of multiple renal vessels has been reported to be from 30% to 49% of patients, with bilaterally occurring multiple vessels in 17%.18,19

Manifestations of Disease

Imaging Indications and Algorithm

Previously, work-up of living renal donors included DSA for mapping of the vasculature prior to harvesting. More recently, noninvasive modalities have become accurate enough to make this assessment. Furthermore, other aspects of the work-up, such as screening for parenchymal or urothelial disease, can be accomplished with a single test. Multidetector CT angiography and CE-MRA have both been shown to be highly sensitive for the detection of main renal arteries and veins, with 100% sensitivity on CT angiography (CTA) and 97% to 100% sensitivity on MRA. CTA has been more sensitive in delineating small accessory renal vessels, such as 1- to 2-mm arteries, with a sensitivity of 100% compared with 20% to 66% for MRA on older MR scanners.20,21 More recently, state of the art MR scanners using parallel imaging for higher resolution and fluoroscopic triggering to ensure accurate bolus timing have shown comparable accuracy to CTA.22 CTA, however, is more sensitive to calculi and urothelial lesions. This must be weighed against the much smaller risks of Gd chelate contrast agent use for CE-MRA versus the risks associated with iodinated contrast use and ionizing radiation exposure associated with CTA.

VASCULAR EVALUATION OF PANCREAS TRANSPLANT RECIPIENTS

Prevalence and Epidemiology

SPK is the most common, accounting for approximately 85% of cases, and PAK and PTA account for approximately 10% and 5% of cases, respectively.23 Improving techniques and therapies have led to increasing viability of pancreas transplants with half-lives of 143, 77, and 90 months for the pancreas portion of SPK, PAK, and PTA transplantations, respectively, performed in 1998 and 1999.

Etiology and Pathophysiology

Vascular complications are more common in pancreatic transplants than in any other solid organ and are the most common cause of early failure.24 Venous thrombosis is the most common vascular dysfunction. Other vascular complications include arterial thrombosis, pseudoaneurysm, arteriovenous fistula, and stenosis.

Manifestations of Disease

Imaging Techniques and Findings

Ultrasound

Color and spectral Doppler ultrasound can usually identify the iliac vessels, donor Y graft, and main graft vessels when the pancreas transplant is visualized.25 However, because of its intraperitoneal location, the graft may be obscured by bowel. As in renal transplants, power Doppler is useful to identify vessels, but diagnosis of venous or arterial thrombosis requires demonstration of a lack of flow on spectral Doppler. A lack of venous flow in combination with reversed or severely dampened diastolic arterial flow has been shown to be highly accurate for venous thrombosis.26 Similarly, arteriovenous fistulas and pseudoaneurysms appear on color Doppler as tissue vibration surrounding a high-flow artery and draining vein or swirling flow within a saccular outpouching from the artery, respectively, but should be confirmed with typical spectral Doppler waveforms.

Magnetic Resonance Angiography

Because of the complex vascular anatomy, CE-MRA, with three-dimensional volumetric data sets, is the modality of choice to evaluate the vascular complications of pancreas transplantation. In a recent study using state of the art high-resolution three-dimensional CE-MRA, all surgically or angiographically proven vascular complications, including venous and arterial thrombosis, arteriovenous fistula, pseudoaneurysm, and stenoses, were diagnosed.27 Occasional false-positives, especially overgrading stenoses, still occur. Direct anatomic visualization of lesions, as in renal transplants, is accomplished with manipulation of MIPs and correlation with the source images. All main vessels and 85% of first-order branches can be visualized. Additional MRI sequences, including parenchymal enhancement, can be used to rule out other causes of graft dysfunction, such as enzymatic leak or peritransplant collections and to assess for possible infarction or infection of the graft.

Bruno S, Giuseppe R, Ruggenenti P. Transplant renal artery stenosis. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2004;15:134-141.

Dobos N, Roberts DA, Insko EK, et al. Contrast-enhanced MR angiography for evaluation of vascular complications of the pancreatic transplant. Radiographics. 2005;25:687-695.

Hernandez D, Rufino M, Armas S, et al. Retrospective analysis of surgical complications following cadaveric kidney transplantation in the modern transplant era. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2006;21:2908-2915.

Hussain SM, Kock MCJM, Ijzermans JNM, et al. MR imaging: a “one-stop shop” modality for preoperative evaluation of potential living kidney donors. Radiographics. 2003;23:505-520.

Kawamoto S, Montgomery RA, Lawler LP, et al. Multi-detector row CT evaluation of living renal donors prior to laparoscopic nephrectomy. Radiographics. 2004;24:453-466.

Nikolaidis P, Amin RS, Hwang CM, et al. Role of sonography in pancreatic transplantation. Radiographics. 2003;23:939-949.

1 2008 Annual Report of the U.S. Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network and the Scientific Registry of Transplant Recipients: Transplant Data 1998-2006. Rockville, Md, Health Resources and Services Administration, Healthcare Systems Bureau, Division of Transplantation, 2008.

2 Tarzamni MK, Argani H, Nurifar M, Nezami N. Vascular complication and Doppler ultrasonographic finding after renal transplantation. Transplant Proc. 2007;39:1096-1102.

3 Fernández-Nájera JE, Beltrán S, Aparicio M, et al. Transplant renal artery stenosis: association with acute vascular rejection. Transplant Proc. 2006;38:2404-2405.

4 Audard V, Matignon M, Hemery F, et al. Risk factors and long-term outcome of transplant renal artery stenosis in adult recipients after treatment by percutaneous transluminal angioplasty. Am J Transplant. 2006;6:95-99.

5 Baxter GM, Ireland H, Moss JG, et al. Colour Doppler ultrasound in renal transplant stenosis: which Doppler index? Clin Radiol. 1995;50:618-622.

6 Loubeyre P, Abidi H, Cahen R, Minh VAT. Transplanted renal artery: detection of stenosis with color Doppler US. Radiology. 1997;203:661-665.

7 Williams GJ, Macaskill P, Chan SF, et al. Comparative accuracy of renal duplex sonographic parameters in the diagnosis of renal artery stenosis: paired and unpaired analysis. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2007;188:798-811.

8 Stafford Johnson DB, Lerner CA, Prince MR, et al. Gadolinium-enhanced magnetic resonance angiography of renal transplants. MRI. 1997;15:13-20.

9 Glicklich D, Tellis VA, Quinn T. Comparison of captopril scan and Doppler ultrasonography as screening tests for transplant renal artery stenosis. Transplantation. 1990;49:217-219.

10 Da Silva RG, Lima VC, Amorim JE, et al. Angioplasty with stent is the preferred therapy for posttransplant renal artery stenosis. Transplant Proceed. 2002;34:514-515.

11 Patel NH, Jindal RM, Wilkin T, et al. Renal arterial stenosis in renal allografts: retrospective study of predisposing factors and outcome after percutaneous transluminal angioplasty. Radiol. 2001;219:663-667.

12 Brandenburg VM, Frank RD, Riehl J. Color-coded duplex sonography study of arteriovenous fistulae and pseudoaneurysms complicating renal allograft biopsy. Clin Nephrol. 2002;58:398-404.

13 Loffroy R, Guiu B, Lambert A, et al. Management of post-biopsy renal allograft arteriovenous fistulas with selective arterial embolization: immediate and long-term outcomes. Clin Radiol. 2008;63:657-665.

14 Renowden SA, Blethyn J, Cochlin DL. Duplex and colour flow sonography in the diagnosis of post-biopsy arteriovenous fistulae in the transplant kidney. Clin Radiol. 1992;45:233-237.

15 Kim HS, Fine DM, Atta MG. Catheter-directed thrombectomy and thrombolysis for acute renal vein thrombosis. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2006;17:815-822.

16 Penny MJ, Nankivell BJ, Disney APS, et al. Renal graft thrombosis, a survey of 134 consecutive cases. Transplant. 1994;58:565-569.

17 Bakir N, Sluiter WJ, Ploeg RJ, et al. Primary renal graft thrombosis. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 1996;11:140-147.

18 Geissing M, Kroencke TJ, Taupitz M, et al. Gadolinium-enhanced three-dimensional magnetic resonance angiography versus conventional digital subtraction angiography: which modality is superior in evaluating living kidney donors? Transplantation. 2003;76:1000-1006.

19 Halpern EJ, Mitchell DG, Wechsler RJ, et al. Preoperative evaluation of living renal donors: comparison of CT angiography and MR angiography. Radiology. 2000;216:434-439.

20 Kim T, Murakami T, Takahashi S, et al. Evaluation of renal arteries in living renal donors: comparison between MDCT angiography and gadolinium-enhanced 3D MR angiography. Radiat Med. 2006;24:617-624.

21 Bhatti AA, Chugtai A, Haslam P, et al. Prospective study comparing three-dimensional computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging for evaluating the renal vascular anatomy in potential living renal donors. BJU Int. 2005;96:1105-1108.

22 Gluecker TM, Mayr M, Schwarz J, et al. Comparison of CT angiography with MR angiography in the preoperative assessment of living kidney donors. Transplantation. 2008;86:1249-1256.

23 Gruessner AC, Sutherland DEC. Long-term results after pancreas transplantation. Transplant Proceed. 2007;39:2323-2325.

24 Benedetti E, Sileri P, Gruessner AC, Cicalese L. Surgical complications of pancreas transplantation. In: Hakim N, Stratta R, Gray D, editors. Pancreas and Islet Transplantation. New York: Oxford University Press; 2002:155-165.

25 Snider JF, Hunter DW, Kuni CC, et al. Pancreatic transplantation: radiologic evaluation of vascular complications. Radiology. 1991;178:749-753.

26 Foshager MC, Hedlund LJ, Troppmann C, et al. Venous thrombosis of pancreatic transplants: diagnosis by duplex sonography. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1997;169:1269-1273.

27 Hagspiel KD, Nandular K, Pruett TL, et al. Evaluation of vascular complications of pancreas transplantation with high-spatial-resolution contrast-enhanced MR angiography. Radiology. 2007;242:590-599.

FIGURE 112-1

FIGURE 112-1

FIGURE 112-2

FIGURE 112-2

FIGURE 112-3

FIGURE 112-3

FIGURE 112-4

FIGURE 112-4

FIGURE 112-5

FIGURE 112-5

FIGURE 112-6

FIGURE 112-6

FIGURE 112-7

FIGURE 112-7

FIGURE 112-8

FIGURE 112-8