Chapter 642 Vascular Disorders

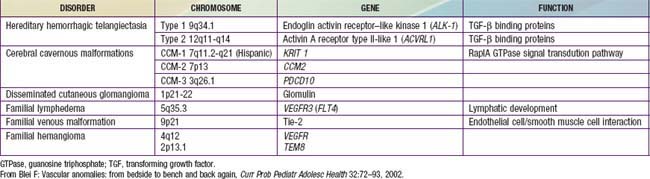

Vascular lesions of childhood may be divided into vascular birthmarks (malformations and tumors), benign acquired disorders, and genetic diseases. Familial disorders may involve arterial, capillary, lymph, or venous malformations (Table 642-1).

Vascular Malformation

Vascular malformations are developmental errors in blood vessel formation. Malformations do not regress but slowly enlarge. They should be named after the predominant blood vessel forming the lesion (Table 642-2). Table 642-3 helps differentiate vascular malformations from true hemangiomas.

| TYPE | EXAMPLE(S) |

|---|---|

| Capillary | Port-wine stain |

| Venous | Venous malformation |

| Angiokeratoma circumscriptum (hyperkeratotic venule) | |

| Cutis marmorata telangiectasia congenita (congenital phlebectasia) | |

| Arterial | Arteriovenous malformation |

| Lymphatic | Superficial lymphatic malformation (lymphangioma circumscriptum) |

| Deep lymphatic malformation with macrocysts and/or microcysts (cystic hygroma) |

Table 642-3 MAJOR DIFFERENCES BETWEEN HEMANGIOMAS AND VASCULAR MALFORMATIONS

| HEMANGIOMAS | VASCULAR MALFORMATIONS (CAPILLARY, VENOUS, LYMPHATIC, ARTERIAL, AND ARTERIOVENOUS, PURE, OR COMPLEX-COMBINED) | |

|---|---|---|

| Clinical | Variably visible at birth | Usually visible at birth (AVMs may be quiescent) |

| Subsequent rapid growth | Growth proportionate to the skin’s growth (or slow progression); present lifelong | |

| Slow, spontaneous involution | ||

| Sex ratio F:M | 3 : 1 to 5 : 1; 7 : 1 in severe cases | 1 : 1 |

| Pathology | Proliferating stage: hyperplasia of endothelial cells and smooth muscle cell actin–positive cells | Flat endothelium |

| Multilaminated basement membrane | Thin basement membrane | |

| Higher mast cell content in involution | Often irregularly attenuated walls (VM, LM) | |

| Radiology | Fast-flow lesion on Doppler sonography | Slow flow (CM, LM, VM) or fast flow (AVM) on Doppler ultrasonography |

| Tumoral mass with flow voids on MRI | MRI: Hyperintense signal on T2-weighted images when slow-flow (LM, VM); flow voids on T1- and T2-weighted images when fast-flow (AVM) | |

| Lobular tumor on arteriogram | Arteriography of AVM demonstrates AV shunting | |

| Bone changes | Rarely mass effect with distortion but no invasion | Slow-flow VM: distortion of bones, thinning, underdevelopment |

| Slow-flow CM: hypertrophy | ||

| Slow-flow LM: distortion, hypertrophy, and invasion of bones | ||

| High-flow AVM: destruction, rarely extensive lytic lesions | ||

| Combined malformations (e.g., slow-flow [capillary lymphatic venous malformation, Klippel-Trenaunay syndrome] or fast-flow [capillary arteriovenous malformation Parkes-Weber syndrome]): overgrowth of limb bones, gigantism | ||

| Immunohistochemistry on tissue samples | Proliferating hemangioma: high expression of PCNA, type IV collagenase, VEGF, urokinase, and bFGF, Glucose transporter-1 |

AVM, Arteriovenous malformation; bFGF, basic fibroblast growth factor; CM, capillary malformation/port-wine stain; LM, lymphatic malformation; LVM, lymphovenous malformation; PCNA, proliferating cell nuclear antigen; VEGF, vascular endothelial growth factor; VM, venous malformation.

From Eichenfield LF, Frieden IJ, Esterly NB: Textbook of neonatal dermatology, Philadelphia, 2001, WB Saunders, p 337.

Capillary Malformation (Port-Wine Stain)

Port-wine stains are present at birth. These vascular malformations consist of mature dilated dermal capillaries. The lesions are macular, sharply circumscribed, pink to purple, and tremendously varied in size (Fig. 642-1). The head and neck region is the most common site of predilection; most lesions are unilateral. The mucous membranes can be involved. As a child matures into adulthood, the port-wine stain may become darker in color and pebbly in consistency; it may occasionally develop elevated areas that bleed spontaneously.

True port-wine stains should be distinguished from the most common vascular malformation, the salmon patch of neonates, which, in contrast, is a relatively transient lesion (Chapter 639). When a port-wine stain is localized to the trigeminal area of the face, specifically around the eyelids, the diagnosis of Sturge-Weber syndrome (glaucoma, leptomeningeal venous angioma, seizures, hemiparesis contralateral to the facial lesion, intracranial calcification) must be considered (Chapter 589.3). Early screening for glaucoma is important to prevent additional damage to the eye. Port-wine stains also occur as a component of Klippel-Trenaunay syndrome and with moderate frequency in other syndromes, including Cobb (spinal arteriovenous malformation, port-wine stain), Proteus, Beckwith-Wiedemann, and Bonnet-Dechaume-Blanc syndromes. In the absence of associated anomalies, morbidity from these lesions may include a poor self-image, hypertrophy of underlying structures, and traumatic bleeding.

Venous Malformation

Malformations consisting of veins only run the gamut from nodules containing a mass of venules (Fig. 642-2) to diffuse large vein abnormalities that may consist of either a superficial component resembling varicose veins, deeper venous malformations, or both. Nodular venous malformations are frequently confused with hemangiomas. Venous malformations may be differentiated by their presence at birth, lack of rapid growth phase, and no tendency toward regression. The treatment of choice for superficial nodular vascular malformations is surgical excision. Treatment of larger vein malformations is at best difficult and often impossible. Percutaneous sclerotherapy with direct injection of polidocanol microfoam, with color Doppler ultrasonographic guidance, is helpful in many patients, including those with Klippel-Trenaunay syndrome.

Cutis Marmorata Telangiectatica Congenita (Congenital Phlebectasia)

Cutis marmorata telangiectatica congenita is benign vascular anomaly that represents dilatation of superficial capillaries and veins and is apparent at birth. Involved areas of skin have a reticulated red or purple hue that resembles physiologic cutis marmorata but is more pronounced and relatively unvarying (Fig. 642-3). The lesions may be restricted to a single limb and a portion of the trunk or may be more widespread. Port-wine stain may also be associated. The lesions become more pronounced during changes in environmental temperature, physical activity, or crying. In some cases, the underlying subcutaneous tissue is underdeveloped, and ulceration may occur within the reticulated bands. Rarely, defective growth of bone and other congenital abnormalities may be present. No specific therapy is indicated. Mild vascular-only cases may show gradual improvement. Adams-Oliver syndrome and cutis marmorata telangiectatica congenita–macrocephaly syndrome are rarely associated disorders.

Arteriovenous Malformation

Arteriovenous malformations (AVMs) are direct connections of artery to vein that bypass the capillary bed (Fig. 642-4). AVMs of the skin are very rare. They are diagnosed from their obvious arterial palpation. Many physicians mistakenly call all vascular malformations AVMs.

Klippel-Trenaunay and Klippel-Trenaunay-Weber Syndromes

Klippel-Trenaunay syndrome (KT) is a cutaneous vascular malformation that, in combination with bony and soft tissue hypertrophy and venous abnormalities, constitutes the triad of defects of this nonheritable disorder (Fig. 642-5). The anomaly is present at birth and usually involves a lower limb but may involve more than one as well as portions of the trunk or face. Enlargement of the soft tissues may be gradual and may involve the entire extremity, a portion of it, or selected digits. The vascular lesion most often is a capillary malformation, generally localized to the hypertrophied area. The deep venous system may be absent or hypoplastic. Venous blebs and/or vesicular lymphatic lesions may be present on the malformation’s surface. Thick-walled venous varicosities typically become apparent ipsilateral to the vascular malformation after the child begins to ambulate. If there is an associated AVM, the disorder is called Klippel-Trenaunay-Weber syndrome (KTW).

Vascular Tumor

Hemangioma

Hemangiomas are proliferative hamartomas of vascular endothelium that may be present at birth or, more commonly, may become apparent in the 1st 2 mo of life, predictably enlarge, and then spontaneously involute. Hemangiomas are the most common tumor of infancy, occurring in 1-2% of newborns (higher in preterm infants) and 10% of white infants in the 1st year of life. Hemangiomas should be classified as superficial, deep, or mixed. The terms strawberry and cavernous should not be used to describe hemangiomas. The immunohistochemical marker GLUT-1 separates hemangiomas from the other vascular tumors of infancy. Superficial hemangiomas are bright red, protuberant, compressible, sharply demarcated lesions that may occur on any area of the body (Figs. 642-6 and 642-7). Although sometimes present at birth, they more often appear in the 1st two months of life and are heralded by an erythematous or blue mark or an area of pallor, which subsequently develops a fine telangiectatic pattern before the phase of expansion. The presenting sign may occasionally be an ulceration of the perineum or lip. Girls are affected more often than boys. Favored sites are the face, scalp, back, and anterior chest; lesions may be solitary or multiple. Patterns of facial involvement include frontotemporal, maxillary, mandibular, and frontonasal regions. Hemangiomas that are more deeply situated are more diffuse and are less defined than superficial hemangiomas. The lesions are cystic, firm, or compressible, and the overlying skin may appear normal in color or may have a bluish hue (Fig. 642-8).

Most hemangiomas are mixed, having both superficial and deep components. Hemangiomas undergo a phase of rapid expansion, followed by a stationary period and finally by spontaneous involution. Regression may be anticipated when the lesion develops blanched or pale gray areas that indicate fibrosis. The course of a particular lesion is unpredictable, but ≈ 60% of these lesions reach maximal involution by 5 yr of age, and 90-95% by 9 yr. Spontaneous involution cannot be correlated with size or site of involvement, but lip lesions seem to persist most often. Complications include ulceration, secondary infection, and, rarely, hemorrhage (Table 642-4). The location of a lesion may interfere with a vital function (e.g., on eyelid interfering with vision, on urethra with urination, on airway with respiration). Hemangiomas in a “beard” distribution may be associated with upper airway or subglottic involvement. Respiratory symptoms should suggest a tracheobronchial lesion. Large hemangiomas may be complicated by coexistent hypothyroidism due to type 3 iodothyronine deiodinase, and symptoms may be difficult to detect in this age group. Other concerning features are listed in Table 642-5.

| CLINICAL FINDING | RECOMMENDED TREATMENT |

|---|---|

| Severe ulceration/maceration | Encourage twice-daily cleansing regimen |

| Dilute sodium bicarbonate soaks | |

| ± Flashlamp pulsed dye laser | |

| ± Oral corticosteroids or propranolol | |

| ± Culture-directed systemic antibiotics for infection | |

| Bleeding (not KMP) | Gelfoam or Surgifoam or propranolol |

| Compression therapy ± embolization | |

| Hemangioma with ophthalmologic sequelae | Patching therapy as directed by ophthalmologist |

| Intralesional vs oral corticosteroids vs propranolol | |

| Subglottic hemangioma | Oral corticosteroids ± potassium titanyl phosphate (KtP) laser |

| Tracheotomy if required | |

| KMP | Corticosteroids, aminocaproic acid, vincristine, interferon-α ± embolization |

| High-flow hepatic hemangioma | Corticosteroids or interferon ± embolization |

KMP, Kasabach-Merritt phenomenon.

From Blei F: Vascular anomalies: from bedside to bench and back again, Curr Prob Pediatr Adolesc Health 32:72–93, 2002.

Table 642-5 CLINICAL “RED FLAGS” ASSOCIATED WITH HEMANGIOMAS

| CLINICAL FINDING | RECOMMENDED EVALUATION |

|---|---|

| Facial hemangioma involving significant area of face | Evaluate for PHACES (posterior fossa abnormalities, hemangioma, and arterial, cardiac, eye, and sternal abnormalities): MRI for orbital hemangioma ± posterior fossa malformation |

| Cardiac, ophthalmologic evaluation | |

| Evaluate for midline abnormality: supraumbilical raphe, sternal atresia, cleft palate, thyroid abnormality | |

| Cutaneous hemangiomas in beard distribution | Evaluate for airway hemangioma, especially if manifesting with stridor |

| Periocular hemangioma |

From Blei F: Vascular anomalies: from bedside to bench and back again, Curr Prob Pediatr Adolesc Health 32:67–102, 2002.

Diffuse Hemangiomatosis

Diffuse hemangiomatosis is a condition in which numerous hemangiomas are widely distributed. The skin usually has many small red papular hemangiomas (Fig. 642-9). Most affected infants have benign neonatal hemangiomatosis, with widespread cutaneous hemangiomas in the absence of apparent visceral involvement. Diffuse neonatal hemangiomatosis is the association of multiple cutaneous hemangiomas of the skin with similar lesions in internal organs. The internal hemangiomas may involve any of the viscera; the liver, gastrointestinal tract, central nervous system, and lungs are the most common sites. In cases of benign neonatal hemangiomatosis, spontaneous regression of the lesions without complications is probable. Infants with diffuse neonatal hemangiomatosis are usually ill at birth. In these cases, ultrasonography and CT are indicated to determine the extent of visceral or neural involvement. The disorder is often fatal because of high-output cardiac failure, visceral hemorrhage, obstruction of the respiratory tract, or compression of central neural tissue. Treatment consists of systemic corticosteroid therapy alone or in combination with vincristine, IFN-α, surgery, or irradiation and support with blood products for erythrocyte, platelet, and coagulation factor consumption.

Tufted Angioma

Tufted angiomas are defined histologically by discrete “cannonball-like” tufts of dermal blood vessels. Two clinical patterns are seen. The classic, more common type is a slowly expanding dusky reddish-blue plaque with satellite lesions. More than 50% of these lesions occur on the head and neck. Regression is not expected. A less common form manifests as a solitary vascular nodule (Fig. 642-10). Clinical differentiation of tufted angioma from a nodular venous malformation is difficult; spontaneous regression of this type of lesion has been reported.

Kasabach-Merritt Syndrome

Kasabach-Merritt syndrome is a life-threatening combination of a rapidly enlarging tufted angioma or kaposiform hemangioendothelioma, thrombocytopenia, microangiopathic hemolytic anemia, and an acute or chronic consumption coagulopathy. The clinical manifestations are usually evident during early infancy. The vascular lesion is usually cutaneous and is only rarely located in viscera. The associated thrombocytopenia may lead to precipitous hemorrhage accompanied by ecchymoses, petechiae, and a rapid increase in the size of the vascular lesion. Severe anemia due to hemorrhage or microangiopathic hemolysis may ensue. The platelet count is depressed, but the bone marrow contains increased numbers of normal or immature megakaryocytes. The thrombocytopenia has been attributed to sequestration or increased destruction of platelets within the lesion. Hypofibrinogenemia and decreased levels of consumable clotting factors are relatively common (Chapter 478.6).

Benign Acquired Vascular Disorders

Pyogenic Granuloma (Lobular Capillary Hemangioma)

A pyogenic granuloma is a small red, glistening, sessile, or pedunculated papule that often has a discernible epithelial collarette (Fig. 642-11). The surface may be weeping and crusted or completely epithelialized. Pyogenic granulomas initially grow rapidly, may ulcerate, and bleed easily when traumatized because they consist of exuberant granulation tissue. They are relatively common in children, particularly on the face, arms, and hands. Such a lesion located on a finger or hand may appear as a subcutaneous nodule. Pyogenic granulomas may arise at sites of injury, but a history of trauma often cannot be elicited. Clinically, they resemble and are often indistinguishable from small hemangiomas. Microscopically, an early pyogenic lesion resembles an early capillary hemangioma. Collarette formation at the base of the tumor and edema of the stroma may allow differentiation from a capillary hemangioma.

Spider Angioma

A vascular spider (nevus araneus) consists of a central feeder artery with many dilated radiating vessels and a surrounding erythematous flush, varying from a few millimeters to several centimeters in diameter (Fig. 642-12). Pressure over the central vessel causes blanching; pulsations visible in larger nevi are evidence for the arterial source of the lesion. Spider angiomas are associated with conditions in which there are increased levels of circulating estrogens, such as cirrhosis and pregnancy, but they also occur in up to 15% of normal preschool-aged children and 45% of school-aged children. Sites of predilection in children are the dorsum of the hand, forearm, face, and ears. Lesions often regress spontaneously after puberty. If removal is desired, PDL is the mode of choice; resolution is achieved in 90% of cases with a single treatment.

Genetic Disorders

Maffucci Syndrome

The association of numerous vascular and, occasionally, lymphatic malformations with nodular enchondromas in the metaphyseal or diaphyseal portion of long bones is known as Maffucci syndrome. Mutations in the PTH/PTHRP type 1 receptor have been identified in the enchondromatoses. Vascular lesions are typically soft, compressible, asymptomatic blue to purple subcutaneous masses that grow in proportion to a child’s growth and stabilize by adulthood. Mucous membranes or viscera may also be involved. Onset occurs during childhood. Bone lesions may produce limb deformities and pathologic fractures. Malignant transformation of enchondromas (chondrosarcoma, angiosarcoma) or primary malignancies (ovarian, fibrosarcoma, glioma, pancreatic) may be a complication (Chapter 495).

Angiokeratoma Corporis Diffusum (Fabry Disease) (Chapter 80.4)

Additional clinical manifestations include recurrent episodes of fever and agonizing pain, cyanosis and flushing of the acral limb areas, paresthesias of the hands and feet, corneal opacities detectable on slit-lamp examination, and hypohidrosis. Renal involvement and cardiac involvement are the usual causes of death. The biochemical defect is a deficiency of the lysosomal enzyme α-galactosidase, with accumulation of ceramide trihexoside in tissues, particularly vascular endothelium, and excretion in urine (see Chapter 80.4 for therapy). Similar cutaneous lesions have also been described in another lysosomal enzyme disorder, α-L-fucosidase deficiency, and in sialidosis, a storage disease with neuraminidase deficiency.

Browning JC, Metry DW. Rapidly involuting congenital hemangioma: case report and review of the literature. Dermatol Online J. 2008;15:11.

Chang LC, Haggstrom AN, Drolet BA, et al. Growth characteristic of infantile hemangiomas: implication for management. Pediatrics. 2008;122:360-367.

2008 Claesson-Welsh: Healing hemangiomas. Nature Med. 2008;14:1147-1148.

Dadlani C, Kamino H, Walters RF, et al. Unilateral nevoid telangiectasia. Dermatol Online J. 2008;14:3.

Drolet BA, Chamlin SL, Garzon MC, et al. Prospective study of spinal anomalies in children with infantile hemangiomas of the lumbosacral skin. J Pediatr. 2010;157:789-794.

Drolet BA, Swanson EA, Frieden IJ. Infantile hemangiomas: an emerging health issue linked to an increased rate of low birth weight infants. J Pediatr. 2008;153:712-715.

Fay A, Nguyen J, Waner M. Conceptual approach to the management of infantile hemangiomas. J Pediatr. 2010;157(6):881-888.

Garzon MC, Huang JT, Enjolras O, et al. Vascular malformations: part 1. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;56:353-370.

Garzon MC, Huang JT, Enjolras O, et al. Vascular malformations: part 2. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;56:541-564.

Guo S, Ni N. Topical treatment for capillary hemangioma of the eyelid using β-blocker solution. Arch Opthalmol. 2010;128(2):255-256.

Huikeshoven M, Koster PHL, de Borgie CAJM, et al. Redarkening of port-wine stains 10 years after pulsed-dye-laser treatment. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:1235-1240.

Iacobas I, Burrows PE, Frieden IJ, et al. LUMBAR: association between cutaneous infantile hemangiomas of the lower body and regional congenital anomalies. J Pediatr. 2010;157:795-801.

Jinnin M, Medici D, Park L, et al. Suppressed NFAT-dependent VEGFR1 expression and constitutive VEGFR2 signaling in infantile hemangioma. Nature Med. 2008;14:1236-1246.

Karen JK, Mengden SJ, Kamino H, Shupack JL. Generalized essential telangiectasia. Dermatol Online J. 2008;14:9.

Kelly KM, Choi B, McFarlane S, et al. Description and analysis of treatments for port-wine stains. Arch Facial Plast Surg. 2005;7:287-294.

Leaute-Labreze C, Dumas de la Roque E, Hubiche T, et al. Propranolol for sever hemangiomas of infancy. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:2649-2651.

Limaye N, Wouters V, Uebelhoer M, et al. Somatic mutations in angiopoietin receptor gene TEK cause solitary and multiple sporadic venous malformations. Nat Genet. 2009;41:118-124.

Maguiness SM, Hoffman WY, McCalmont TH, et al. Early white discoloration of infantile hemangioma. Arch Dermatol. 2010;14(11):1235-1239.

Mendonca DA, McCafferty I, Nishikawa H, et al. Venous malformations of the limbs: the Birmingham experience, comparisons and classification in children. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2010;63:383-389.

Metry DW, Haggstrom AN, Drolet BA, et al. A prospective study of PHACE syndrome in infantile hemangiomas: demographic features, clinical findings, and complications. Am J Med Genet. 2006;140:975-986.

Metry D, Heyer G, Hess C, et al. Consensus statement on diagnostic criteria for PHACE syndrome. Pediatrics. 2009;124(5):1447-1456.

North PE, Waner M, Buckmiller L, et al. Vascular tumors of infancy and childhood: beyond capillary hemangioma. Cardiovasc Pathol. 2006;15:303-317.

Pavlaković H, Kietz S, Lauerer P, et al. Hyperkalemia complicating propranolol treatment of an infantile hemangioma. Pediatrics. 2010;126(6):e1589-e1593.

Pope E, Krafchik BR, Macarthur C, et al. Oral versus high-dose pulse corticosteroids for problematic infantile hemangiomas: a randomized, controlled trial. Pediatrics. 2007;119:e1239-e1247.

Saint-Jean M, Léauté-Labreze C, Mazereeuw-Hautier J, et al. Propranolol for treatment of ulcerated infantile hemangiomas. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;64(5):827-832.

Siegfried EC, Keenan WJ, Al-Jureidini S. More on propranolol for hemangiomas of infancy. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:2846-2847.

Tan ST, Itinteang T, Leadbitter P. Low-dose propranolol for multiple hepatic and cutaneous hemangiomas with deranged liver function. Pediatrics. 2011;127:e772-e776.