Vascular Conditions

Renovascular Hypertension

Overview: Approximately 5% to 10% of children and adolescents with severe hypertension have an underlying renal vascular lesion. In infants, up to 70% of clinically significant hypertension is due to renovascular disease. Myriad developmental and acquired causes of renovascular hypertension exist (Box 117-1). A complication related to umbilical artery catheterization is the most common cause of renovascular hypertension in neonates. In older children, renal arterial fibromuscular dysplasia is the most common cause.1–4

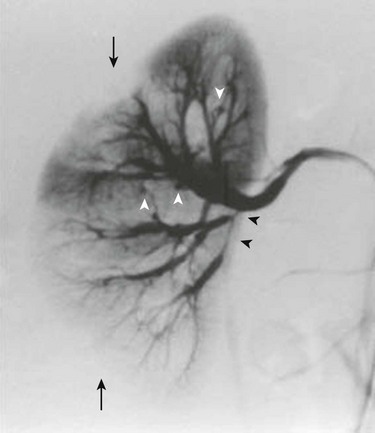

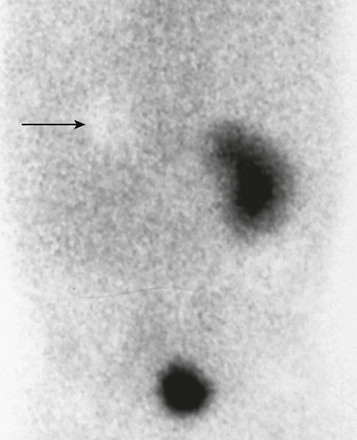

Imaging: Asymmetry of the kidneys on sonography is an important sign of possible renovascular hypertension. The affected kidney often is small and may have manifestations of scarring. Direct visualization of a stenotic renal arterial lesion is uncommon with sonography, however. Evaluation of the aorta also is an important component of the examination. With Doppler evaluation, a renal artery-to-aorta peak systolic velocity ratio of greater than 3.5 carries a strong association with renal arterial stenosis. A peak velocity in the renal artery of greater than 180 cm/s also is suggestive of renal artery stenosis. Distal to the stenotic lesion, the systolic peak of the renal arterial waveform often appears flattened (Fig. 117-1). With severe stenosis, Doppler evaluation of distal arteries shows a tardus-parvus pattern, with slow systolic acceleration and diminished peak systolic velocity. Diastolic flow in the main renal artery sometimes is elevated.5

Figure 117-1 Renal artery stenosis.

Doppler evaluation of the renal artery distal to a severe stenosis in a child with renal fibromuscular dysplasia shows a low-velocity monophasic arterial waveform.

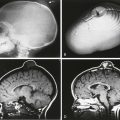

The most useful scintigraphic technique for detection of renovascular hypertension involves the evaluation of renal function without and with the use of an angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor, usually captopril or enalaprilat. MAG3 is the optimal imaging agent for this study. In the presence of renovascular disease, imaging in conjunction with angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor therapy typically shows diminished perfusion, diminished initial uptake, and poor parenchyma clearance of the affected kidney. Comparative imaging in the absence of antihypertensive therapy shows improved function (Fig. 117-2). The sensitivity of this technique for the detection of renovascular hypertension is approximately 85% to 90%. Bilateral renal artery stenosis or markedly compromised renal function can lead to false-negative examinations.6

Figure 117-2 Renovascular hypertension and angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibition scintigraphy.

A, A renogram shows normal uptake and excretion from both kidneys. B, A renogram after administration of an ACE inhibitor shows marked radiopharmaceutical retention in the left kidney, indicating renal artery stenosis. (Courtesy Douglas F. Eggli, MD, Hershey, PA.)

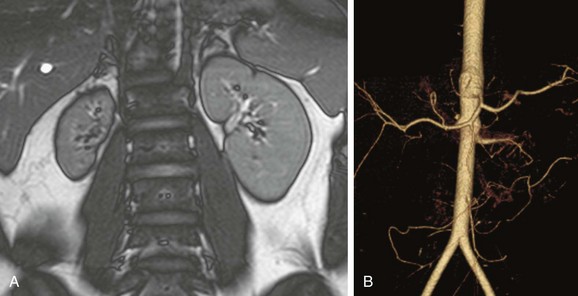

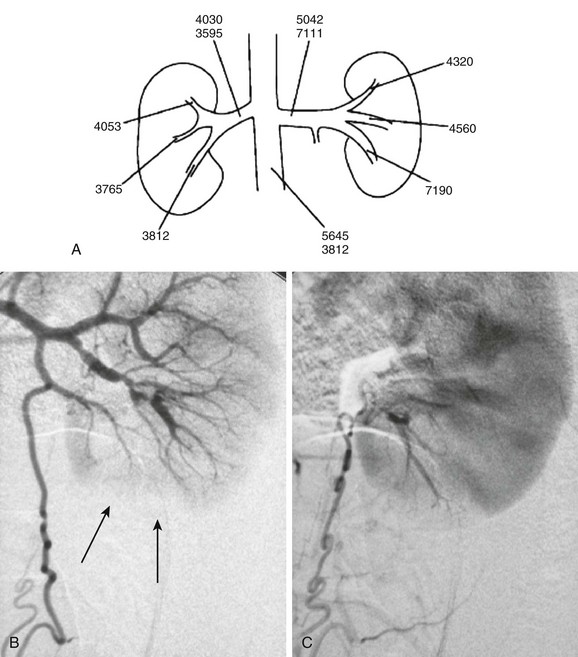

Transcatheter angiography is the most sensitive and specific technique for the detection and identification of small-vessel renal artery disease. Computed tomographic angiography (CTA) and magnetic resonance angiography (MRA) are important noninvasive techniques for visualization of renal vascular anatomy. Upon administration of contrast material, global and regional alterations in kidney perfusion and function also can be assessed with computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). In general, >50% narrowing of the renal arterial diameter is hemodynamically significant. The presence of enlarged collateral pathways is an additional indicator of significant renal artery stenosis. Transcatheter renal vein renin sampling is useful in selected cases of suspected renal hypertension (Fig. 117-3).7,8

Figure 117-3 An 11-year-old girl with hypertension.

A, A map of renal vein renin activity shows that the hypertension is driven by a focus in the left lower pole. B, Arterial phase angiography shows complex segmental stenoses, an area of delayed perfusion owing to a “missing vessel” (arrows), and a prominent collateral ureteric artery. C, Capillary phase angiography shows that the ureteric artery collateral reconstitutes the “missing vessel,” completing the nephrogram. (From Roebuck DJ. Paediatric interventional radiology. Imaging. 2001;13:302-320.)

Renal Fibromuscular Dysplasia

Overview: Renal fibromuscular dysplasia (FMD; arterial fibrous dysplasia) is the most common cause of renal artery stenosis in children. Subcategorization of FMD is based on the layer of the arterial wall that is involved. This classification is important because each type of FMD has distinct histologic and angiographic features and occurs in a different clinical setting.9–11

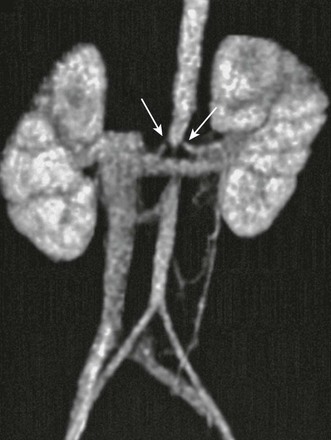

Primary intimal fibroplasia is characterized by circumferential accumulation of collagen subintimally and within the internal elastic membrane. This form of FMD is the most common cause of renal artery stenosis in children. Imaging shows a smooth, bandlike, tubular, or funnel-shaped stenosis that usually involves the distal two thirds of the renal artery or a branch vessel (Fig. 117-4).

Neurofibromatosis

Overview: The most common vascular pathology in patients with neurofibromatosis type 1 involves stenosis of the aorta or a large branch vessel as a result of proliferation of neural tissue in the arterial wall and perivascular space. Occasionally, an aneurysm occurs. In the kidney, a small-vessel mesodermal dysplasia also can occur. Arterial stenosis usually occurs at the vessel origin or in the proximal third of the main renal artery. Concomitant aortic stenosis is common.12

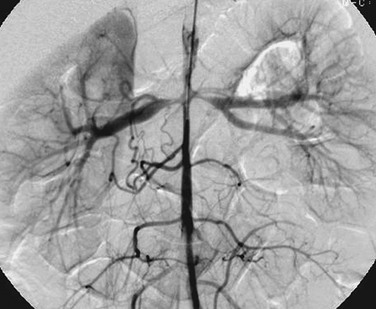

Takayasu Arteritis

Overview: Takayasu arteritis is a rare idiopathic chronic inflammatory arteritis. Hypertension as a result of renal arterial stenosis or abdominal aortic narrowing is common. CT and MRI features of Takayasu arteritis include narrowing, mural thickening, adherent thrombus, and mural calcification of the aorta, pulmonary arteries, and major aortic branch vessels (Fig. 117-5). With active disease, the thickened vascular wall has prominent contrast enhancement.13–15

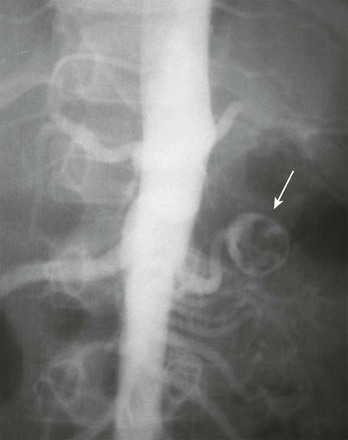

Middle Aortic Syndrome

Overview: Middle aortic syndrome (midaortic dysplastic syndrome) is an acquired, progressive vascular disorder that involves the midthoracic through abdominal segments of the aorta and usually is accompanied by narrowing of major visceral branches, including the renal arteries. Imaging studies show diffuse narrowing of the thoracoabdominal segment of the aorta and the major branch vessels (Figs. 117-6 and 117-7). If renal artery narrowing is severe, collateral flow to the kidneys usually occurs via ureteral, adrenal, and gonadal arteries that fill from lower intercostal vessels.16,17

Renovascular Trauma

Overview: Potential renal arterial injuries include intimal disruption, main renal artery avulsion, branch vessel transection, false aneurysm, and arteriovenous fistula. Most renal injuries in children result from blunt trauma; penetrating injuries are uncommon. The intima is most susceptible to a stretching injury because it is less elastic than the media and the adventitia. An intimal tear can precipitate dissection, luminal occlusion, or thrombosis. Stretching injury also can cause spasm of the renal artery without a tear. With severe, rapid motion of the kidney, vascular avulsion can occur. Penetrating injuries and iatrogenic mechanisms such as a needle biopsy can lead to an intrarenal arteriovenous fistula.18

Imaging: Globally deficient parenchymal contrast enhancement is an important CT indicator of possible disruption, thrombosis, or spasm of the main renal artery. Contrast enhancement in the periphery of an ischemic kidney (the “cortical rim sign”) is a radiographic indicator of acute renal arterial occlusion. The cortical rim sign does not develop until at least 8 hours after the onset of ischemia; in many patients, it is not present until a few days after the injury. This sign generally indicates that renal salvage is not possible because of the prolonged nature of the ischemia.

Aneurysm

Overview: Renal artery aneurysms are rare in childhood. Classifying features include location (extraparenchymal and intraparenchymal) and morphology (saccular, fusiform, dissecting, and false). Some pediatric renal artery aneurysms are idiopathic; others are due to infection (i.e., mycotic aneurysms), renal artery stenosis (often related to neurofibromatosis type 1 or fibromuscular dysplasia), or autoimmune vasculitis (e.g., polyarteritis nodosa). Aneurysms of the renal artery can occur in patients with Kawasaki disease and Ehlers-Danlos syndrome. The most common clinical manifestations of a renal artery aneurysm are hematuria and flank pain.19

Imaging: Renal artery aneurysms can be single or multiple; most are saccular. A clot or calcification occasionally is present within the aneurysm (Fig. 117-8). Aneurysms that occur in patients with polyarteritis nodosa tend to be small, multiple, and intraparenchymal. Most are detectable with sonography, CTA, or MRA. Conventional angiography sometimes is required for the detection and characterization of small lesions.20

Arteriovenous Malformation and Fistula

Overview and Imaging: About three quarters of renal arteriovenous fistulas are iatrogenic or related to trauma. Congenital arteriovenous malformations of the kidney are rare. Hematuria and a bruit are common clinical findings. A large lesion can cause congestive heart failure. Imaging studies of a renal arteriovenous fistula show a focal abnormal direct communication between an artery and a vein, whereas shunting in an arteriovenous malformation occurs through a nidus of abnormal vessels. Supplying and draining vessels are enlarged. Doppler analysis shows turbulent flow and arterial velocity in the draining veins. Conventional angiography shows rapid flow through the lesion.21,22

Thrombosis, Embolism, and Infarction

Overview: Thromboembolic disease of the renal arteries is uncommon in children. Predisposing conditions include sepsis, prolonged hypotension, severe dehydration, congenital heart disease, trauma, and hypercoagulable disorders. In neonates, the most common cause is an umbilical arterial catheter, particularly when the catheter tip is near the origins of the renal arteries. Infants of diabetic mothers are at increased risk for renal arterial thrombosis. In older children, acute occlusion of a major renal artery causes flank pain, nausea, vomiting, fever, and hematuria. Small emboli or minor thrombosis may be asymptomatic, although hypertension is a common complication.23

Imaging: In the acute phase of renal artery thromboembolism, sonography is normal or shows nonspecific renal enlargement and cortical hyperechogenicity. Doppler evaluation sometimes reveals global, focal, or multifocal perfusion deficits. Flow within the capsule may be increased. Careful evaluation of the main renal artery sometimes demonstrates an echogenic clot, as well as abnormal arterial waveforms. If the main renal artery is patent in a patient with renal infarction, the resistive index often is elevated.

CTA and MRA of patients with renal arterial thromboembolic disease may reveal filling defects or narrowing of the renal artery. With global renal infarction, renal parenchymal enhancement and normal contrast media excretion are lacking. One or more wedge-shaped enhancement defects may occur in the presence of segmental renal infarction. In about 50% of patients with renal infarction, a thin, prominently enhancing rim is visible at the peripheral margin of an infarction (Fig. 117-9).

Diseases of the Intrarenal Arteries

Overview: The kidney is a relatively common site of involvement in various forms of vasculitis. The most widely used classification of vasculitis is based on the size of the predominantly involved vessels. Takayasu arteritis is an example of large-vessel vasculitis. Polyarteritis nodosa and Kawasaki disease predominantly involve medium-sized vessels. The presence or absence of antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies (ANCAs) allows subcategorization of the small-vessel vasculitides. Henoch-Schönlein purpura (HSP) is ANCA negative; ANCA-positive vasculitides that can affect the kidney include Wegener granulomatosis and microscopic polyarteritis. Small-vessel vasculitis also can occur in association with various infectious diseases, such as Rocky Mountain spotted fever, human immunodeficiency virus, hepatitis B, and tuberculosis.24

Polyarteritis Nodosa

Overview: Polyarteritis nodosa is a rare idiopathic focal segmental necrotizing vasculitis. Renal involvement occurs in slightly more than half of affected children. Clinical manifestations of kidney involvement include hematuria, proteinuria, and hypertension. Imaging studies of the kidneys may show manifestations of focal or multifocal renal ischemia. Intraparenchymal or perirenal hemorrhage can occur as the result of aneurysm rupture. Arteriography reveals small aneurysms, typically located at the bifurcations of interlobular or arcuate arteries. Small intrarenal vessels are irregular and tortuous because of vascular and perivascular inflammation (Fig. 117-10).25

Wegener Granulomatosis and Microscopic Polyarteritis

Overview: Wegener granulomatosis is a rare necrotizing vasculitis that predominantly affects the respiratory tract. Up to 80% of patients have evidence of renal involvement, as manifested by hematuria, proteinuria, and (in many patients) diminished glomerular filtration rate. Similar clinical findings occur in patients with microscopic polyarteritis, although respiratory system involvement is lacking with this disorder. Diagnostic imaging findings of kidney involvement with these two vasculitides are nonspecific. Foci of parenchymal scarring may occur as the result of ischemia. Parenchymal or perirenal hemorrhage can occur as a result of rupture of a small-vessel aneurysm. The imaging findings are similar to those of polyarteritis nodosa.26,27

Systemic Lupus Erythematosus

Overview: Systemic lupus erythematosus is a systemic autoimmune disease. Up to 75% of children with this disorder have clinical manifestations of renal involvement. A clinical spectrum ranges from mild asymptomatic disease to severe forms that lead to end-stage renal disease or death. The major pathologic manifestation is thickening of the basement membrane as a result of focal glomerulonephritis; inflammatory narrowing of interlobular arteries also may be evident. In the absence of renal failure, the kidneys often appear normal on imaging studies. Mild nephromegaly is common. Diffuse or multifocal hyperechogenicity of the renal parenchyma may be present on sonography. Elevation of the resistive index on Doppler ultrasonography may be predictive of worsening renal function.28,29

Hemolytic-Uremic Syndrome

Overview: Hemolytic-uremic syndrome is the most common cause of acute renal failure in early childhood. The pathogenesis involves endothelial cell damage within glomeruli and renal arterioles. The kidney is the main target of this microangiopathy, although the intestines, lung, and brain variably are affected. In most cases of hemolytic-uremic syndrome, fever, vomiting, bloody diarrhea, and abdominal discomfort develop in an otherwise healthy infant. Affected children beyond infancy are usually around 3 years of age. The child may become critically ill, with signs and symptoms that include pallor, irritability, seizures, heart failure, hypertension, gastrointestinal bleeding, and oliguria. Acute renal failure usually lasts for 1 to 4 weeks, with subsequent slow improvement. Clinical recovery is complete in most patients, but some children have permanent neurologic or renal damage.30

Imaging: Early in the disease, sonography is normal or shows minimal nephromegaly. Subsequent abnormally increased parenchymal echogenicity usually is most prominent in the glomerular and subcortical regions. The degree of cortical echogenicity correlates with the severity of the illness. In most patients, the kidney returns to a normal size as the disease resolves, but more severe injury is associated with eventual kidney atrophy; nephrocalcinosis can occur.31,32

Henoch-Schönlein Purpura

Overview: HSP is a hypersensitivity vasculitis that affects small vessels and is an important cause of nephritis in children. The clinical tetrad includes a purpuric rash, arthralgias, abdominal pain, and glomerulonephritis. Between 20% to 30% of patients with HSP have hematuria, and 30% to 70% have proteinuria. In patients with profound proteinuria, nephrotic syndrome and renal insufficiency can occur. Clinical signs of renal involvement may follow or coincide with the appearance of purpura, but they rarely antedate the skin findings. HSP usually is a self-limited disorder, but it can be complicated by hypertension or chronic renal failure.33,34

Imaging: Sonography of patients with HSP may show normal or bilaterally enlarged kidneys. Hyperechogenicity of the renal cortex is usually diffuse, and the medullary pyramids remain hypoechoic. Renal cortical hyperechogenicity diminishes as the acute disease regresses. Occasionally, cross-sectional imaging studies show an intramural hematoma of the bladder wall or ureter. Ureteral fibrosis is a rare complication.

Sickle Cell Disease

Overview: Sludging of red blood cells within the medulla is common in patients with sickle cell disease. Recurrent episodes of medullary ischemia lead to alterations in papillary morphology. Papillary necrosis develops when medullary ischemia is severe. Cortical hypertrophy may occur. Nephropathy of sickle cell disease involves the entire renal parenchyma. Histologic features include dilation and engorgement of cortical capillary tufts, glomerulosclerosis, increased mesangial matrix, and iron deposition in the glomerular epithelium and glomerular basement membrane. Occasionally, glomerular sclerosis progresses to complete obliteration of glomerular tufts.35

Imaging: Intravenous urography and CT may show calyceal blunting and prominent papillae with broad, deep calyces. The collecting system often is distorted because of cortical hypertrophy (Fig. 117-11). In some patients, papillary necrosis is evident. Nephromegaly, usually bilateral, is common. Recurrent infarction and subsequent fibrosis eventually may lead to scarring and atrophy.36

Figure 117-11 Sickle cell disease.

An intravenous urogram of a 13-year-old child with sickle cell disease shows calyceal dilation and collecting system distortion.

Renal sonography of patients with sickle cell disease typically shows mild diffuse enlargement, hyperechogenicity, and loss of corticomedullary differentiation (Fig. 117-12). A perirenal hematoma can occur as a complication of renal infarction. Doppler sonography serves to detect renovascular disease. MRI shows decreased cortical signal relative to the medulla on T1-weighted and T2-weighted images as a result of iron deposition in the renal cortex.37,38

Renal Vein Thrombosis

Overview: Renal vein thrombosis (RVT) is the most common renal vascular abnormality of neonates. Most affected infants have a predisposing systemic abnormality such as dehydration, sepsis, polycythemia, or maternal diabetes mellitus. Small intrarenal vessels are the initial or only site of thrombosis in many cases of RVT. Propagation of a central venous catheter–related inferior vena cava clot is an additional potential mechanism. Renal vein thrombosis in older patients can occur as the result of nephrotic syndrome, glomerulonephritis, a hypercoagulable state, trauma, or a retroperitoneal tumor. Typical clinical manifestations of RVT include nephromegaly, signs of renal insufficiency, hematuria, and hypertension.39

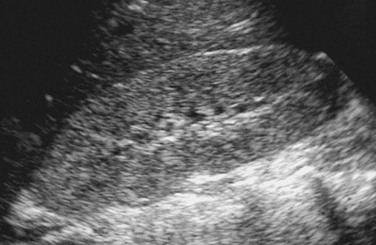

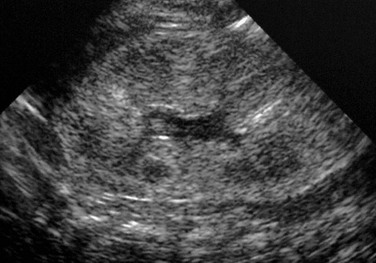

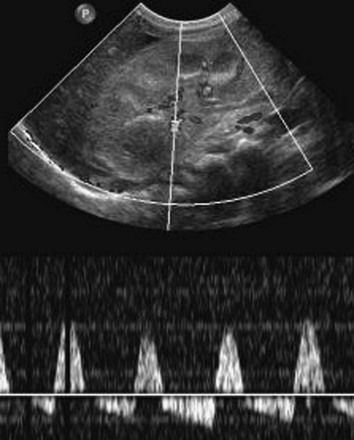

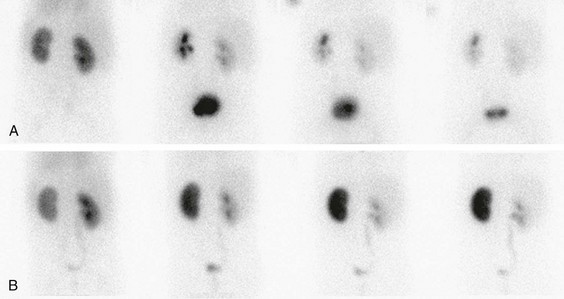

Imaging: The typical sonographic features of RVT are abnormal parenchymal echogenicity and loss of corticomedullary differentiation; in some cases, interlobular echogenic streaks are present (Fig. 117-13). Interstitial hemorrhage occasionally leads to parenchymal hyperechogenicity. Elevation of the arterial resistive index occurs as a result of venous outflow obstruction (Fig. 117-14). Narrowing of the systolic peak also is common. Careful sonographic evaluation of the renal veins sometimes reveals an echogenic clot; however, the absence of a clot within the major renal veins does not exclude the diagnosis of small vessel renal vein thrombosis. With severe involvement, Doppler evaluation may show an absence of flow within the main renal vein. In other patients, renal vein flow is monophasic.40–42

Treatment and Follow-up: Therapy of RVT is supportive and directed toward treatment of the underlying cause. Renal scintigraphy during the acute phase provides prognostic information; mild compromise of uptake and excretion indicates a good prognosis (Fig. 117-15). Within a few weeks of onset of RVT, the affected kidney decreases in size. In some patients, progression to global atrophy occurs. Follow-up imaging occasionally demonstrates a reticular pattern of calcification within the intrarenal veins; this finding is essentially pathognomonic of previous renal vein thrombosis.

Cakar, N, Ozcakar, ZB, Soy, D, et al. Renal involvement in childhood vasculitis. Nephron Clin Pract. 2008;108(3):c202–c206.

Lau, KK, Stoffman, JM, Williams, S, et al. Neonatal renal vein thrombosis: review of the English-language literature between 1992 and 2006. Pediatrics. 2007;120(5):e1278–e1284.

Olin, JW, Sealove, BA. Diagnosis, management, and future developments of fibromuscular dysplasia. J Vasc Surg. 2011;53(3):826–836. e821

Tullus, K, Brennan, E, Hamilton, G, et al. Renovascular hypertension in children. Lancet. 2008;371(9622):1453–1463.

References

1. Tullus, K, Brennan, E, Hamilton, G, et al. Renovascular hypertension in children. Lancet. 2008;371(9622):1453–1463.

2. Estepa, R, Gallego, N, Orte, L, et al. Renovascular hypertension in children. Scand J Urol Nephrol. 2001;35(5):388–392.

3. Mentser, M, Mahan, J, Koff, S. Contemporary approaches to renovascular hypertension in children. Pediatr Nephrol. 1995;9(3):386–388.

4. Hiner, LB, Falkner, B. Renovascular hypertension in children. Pediatr Clin North Am. 1993;40(1):123–140.

5. Radermacher, J, Chavan, A, Schaffer, J, et al. Detection of significant renal artery stenosis with color Doppler sonography: combining extrarenal and intrarenal approaches to minimize technical failure. Clin Nephrol. 2000;53(5):333–343.

6. Abdulsamea, S, Anderson, P, Biassoni, L, et al. Pre- and postcaptopril renal scintigraphy as a screening test for renovascular hypertension in children. Pediatr Nephrol. 2010;25(2):317–322.

7. Visrutaratna, P, Srisuwan, T, Sirivanichai, C. Pediatric renovascular hypertension in Thailand: CT angiographic findings. Pediatr Radiol. 2009;39(12):1321–1326.

8. Vo, NJ, Hammelman, BD, Racadio, JM, et al. Anatomic distribution of renal artery stenosis in children: implications for imaging. Pediatr Radiol. 2006;36(10):1032–1036.

9. Olin, JW, Sealove, BA. Diagnosis, management, and future developments of fibromuscular dysplasia. J Vasc Surg. 2011;53(3):826–836. [e821].

10. Sabharwal, R, Vladica, P, Coleman, P. Multidetector spiral CT renal angiography in the diagnosis of renal artery fibromuscular dysplasia. Eur J Radiol. 2007;61(3):520–527.

11. Willoteaux, S, Faivre-Pierret, M, Moranne, O, et al. Fibromuscular dysplasia of the main renal arteries: comparison of contrast-enhanced MR angiography with digital subtraction angiography. Radiology. 2006;241(3):922–929.

12. Booth, C, Preston, R, Clark, G, et al. Management of renal vascular disease in neurofibromatosis type 1 and the role of percutaneous transluminal angioplasty. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2002;17(7):1235–1240.

13. Cakar, N, Yalcinkaya, F, Duzova, A, et al. Takayasu arteritis in children. J Rheumatol. 2008;35(5):913–919.

14. McCulloch, M, Andronikou, S, Goddard, E, et al. Angiographic features of 26 children with Takayasu’s arteritis. Pediatr Radiol. 2003;33(4):230–235.

15. Nastri, MV, Baptista, LP, Baroni, RH, et al. Gadolinium-enhanced three-dimensional MR angiography of Takayasu arteritis. Radiographics. 2004;24(3):773–786.

16. Sethna, CB, Kaplan, BS, Cahill, AM, et al. Idiopathic mid-aortic syndrome in children. Pediatr Nephrol. 2008;23(7):1135–1142.

17. Adams, WM, John, PR. US demonstration and diagnosis of the midaortic syndrome. Pediatr Radiol. 1998;28(6):461–463.

18. Knudson, MM, Harrison, PB, Hoyt, DB, et al. Outcome after major renovascular injuries: a Western trauma association multicenter report. J Trauma. 2000;49(6):1116–1122.

19. Callicutt, CS, Rush, B, Eubanks, T, et al. Idiopathic renal artery and infrarenal aortic aneurysms in a 6-year-old child: case report and literature review. J Vasc Surg. 2005;41(5):893–896.

20. Sarkar, R, Coran, AG, Cilley, RE, et al. Arterial aneurysms in children: clinicopathologic classification. J Vasc Surg. 1991;13(1):47–56. [discussion 56-57].

21. Renowden, SA, Blethyn, J, Cochlin, DL. Duplex and colour flow sonography in the diagnosis of post-biopsy arteriovenous fistulae in the transplant kidney. Clin Radiol. 1992;45(4):233–237.

22. Riccabona, M, Schwinger, W, Ring, E. Arteriovenous fistula after renal biopsy in children. J Ultrasound Med. 1998;17(8):505–508.

23. Kavaler, E, Hensle, TW. Renal artery thrombosis in the newborn infant. Urology. 1997;50(2):282–284.

24. Cakar, N, Ozcakar, ZB, Soy, D, et al. Renal involvement in childhood vasculitis. Nephron Clin Pract. 2008;108(3):c202–c206.

25. Brogan, PA, Davies, R, Gordon, I, et al. Renal angiography in children with polyarteritis nodosa. Pediatr Nephrol. 2002;17(4):277–283.

26. Bansal, PJ, Tobin, MC. Neonatal microscopic polyangiitis secondary to transfer of maternal myeloperoxidase-antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody resulting in neonatal pulmonary hemorrhage and renal involvement. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2004;93(4):398–401.

27. Aasarod, K, Iversen, BM, Hammerstrom, J, et al. Wegener’s granulomatosis: clinical course in 108 patients with renal involvement. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2000;15(12):2069.

28. Stanley, JH, Cornella, R, Loevinger, E, et al. Sonography of systemic lupus nephritis. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1984;142(6):1165–1168.

29. Kirby, JM, Jhaveri, KS, Maizlin, ZV, et al. Abdominal manifestations of systemic lupus erythematosus: spectrum of imaging findings. Can Assoc Radiol J. 2009;60(3):121–132.

30. Siegler, R, Oakes, R. Hemolytic uremic syndrome; pathogenesis, treatment, and outcome. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2005;17(2):200–204.

31. Kraus, RA, Gaisie, G, Young, LW. Increased renal parenchymal echogenicity: causes in pediatric patients. Radiographics. 1990;10(6):1009–1018.

32. Choyke, PL, Grant, EG, Hoffer, FA, et al. Cortical echogenicity in the hemolytic uremic syndrome: clinical correlation. J Ultrasound Med. 1988;7(8):439–442.

33. Davin, JC. Henoch-Schonlein purpura nephritis: pathophysiology, treatment, and future strategy. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2011;6(3):679–689.

34. Trapani, S, Micheli, A, Grisolia, F, et al. Henoch Schonlein purpura in childhood: epidemiological and clinical analysis of 150 cases over a 5-year period and review of literature. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2005;35(3):143–153.

35. Scheinman, JI. Sickle cell disease and the kidney. Nat Clin Pract Nephrol. 2009;5(2):78–88.

36. Dyer, RB, Chen, MYM, Zagoria, RJ. Intravenous urography: technique and interpretation. Radiographics. 2001;21(4):799–824.

37. Taori, KB, Chaudhary, RS, Attarde, V, et al. Renal Doppler indices in sickle cell disease: early radiologic predictors of renovascular changes. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2008;191(1):239–242.

38. Lande, IM, Glazer, GM, Sarnaik, S, et al. Sickle-cell nephropathy: MR imaging. Radiology. 1986;158(2):379–383.

39. Lau, KK, Stoffman, JM, Williams, S, et al. Neonatal renal vein thrombosis: review of the English-language literature between 1992 and 2006. Pediatrics. 2007;120(5):e1278–e1284.

40. Elsaify, WM. Neonatal renal vein thrombosis: grey-scale and Doppler ultrasonic features. Abdom Imaging. 2009;34(3):413–418.

41. Hibbert, J, Howlett, DC, Greenwood, KL, et al. The ultrasound appearances of neonatal renal vein thrombosis. Br J Radiol. 1997;70(839):1191–1194.

42. Alexander, AA, Merton, DA, Mitchell, DG, et al. Rapid diagnosis of neonatal renal vein thrombosis using color Doppler imaging. J Clin Ultrasound. 1993;21(7):468–471.