CHAPTER 8 Vaginal Infections and Sexually Transmitted Diseases

VULVOVAGINITIS AND COMMON VAGINAL INFECTIONS

The normal vaginal environment is a dynamic milieu with a constantly changing balance of Lactobacillus acidophilus and other endogenous flora, glycogen, estrogen, pH, and metabolic byproducts of flora and pathogens.1 L. acidophilus produces hydrogen peroxide that limits the growth of pathogenic bacteria.2 Disturbances in the vaginal environment can allow the proliferation of vaginitis-causing organisms. The term vulvovaginitis actually encompasses a variety of inflammatory lower genital tract disorders that may be secondary to infection, irritation, allergy, or systemic disease.3 Vulvovaginitis is the most common reason for gynecologic visits, with over 10 million office visits for vaginal discharge annually.4 It is usually characterized by vaginal discharge, vulvar itching and irritation, and sometimes vaginal odor.5 Up to 90% of vaginitis is secondary to bacterial vaginosis (BV), vulvovaginal candidiasis (VVC), and trichomoniasis. The actual prevalence and causes of vaginitis, however, are hard to gauge because of the frequency of self-diagnosis and self-treatment.1 In one survey of 105 women with chronic vaginal symptoms, 73% had self-treated with OTC products and 42% had used alternative therapies. On self-assessment, most women thought they had recurrent vulvovaginal candidiasis (RVVC), but upon diagnosis, only 28% were found positive for RVVC. Women with a prior diagnosis of vulvovaginal candidiasis (VVC), however, were able to accurately self-diagnose up to 82% of the time based solely on symptoms.6 This may, however, be an overestimate, as in another study (questionnaire) of 634 women, only 11% were able to accurately recognize the classic symptoms of VVC.6 Another study of women who thought they had VVC also found that self-assessment had limited accuracy, with only 33.7% of women with self-diagnosed yeast infection having microscopically confirmable cases.7

Two-thirds of patients with vaginal discharge have an infectious cause.2 However, the presence of some amount of vaginal secretions can be normal, varying with age, the menstrual cycle, pregnancy, and the use of OCs.

Antibiotics, contraceptives, vaginal intercourse, receptive oral sex, stress, and hormones (e.g., HRT, endogenous hormonal dysregulation) can lead to overgrowth of pathogenic organisms.1 Chemical vulvovaginitis can be caused by colored and perfumed soaps, toilet paper, bubble baths, panty liners, tampons, sanitary pads, and douches. Latex condoms, topical antifungal agents, and preservatives and other agents in lubricants can cause allergic reactions leading to vulvovaginitis.2 In menopausal women, or those on antiestrogen therapies, decreased estrogen levels may lead to atrophic vaginitis, which if asymptomatic generally requires no treatment. Forty percent of postmenopausal women, however, are symptomatic; symptoms are readily treatable with topically applied lubricants, and the use of estrogen replacement therapies by topical or oral administration.

Although vaginal complaints may commonly be treated based on symptoms, studies have demonstrated a poor correlation between symptoms and diagnosis.8,9 Therefore, the most accurate diagnoses and thus the most appropriate treatments, can best be made with testing methods specific for individual organisms. Acute singular episodes of vaginal infections are referred to as uncomplicated, whereas recurrent vaginal infections are considered complicated. Complicated cases are often more severe, resistant to treatment, and may be associated with underlying systemic causes, for example, in VVC, uncontrolled diabetes, or immunosuppression.2

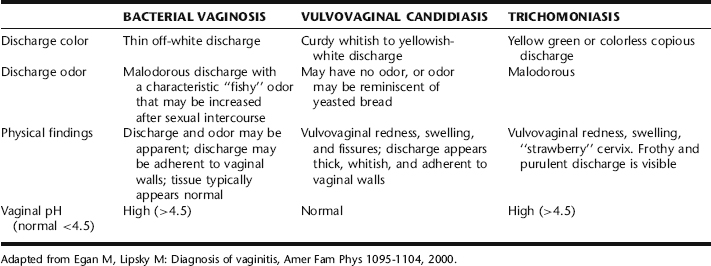

The remainder of this section presents seperate discussions of the most common vaginal infections (Table 8-1) followed by a discussion of the botanical treatment of vaginal infections. Table 8-2 provides a general overview of common causative organisms, agents, and conditions involved in vulvovaginitis. It should be remembered that multiple causes of vaginitis may occur concurrently.2

TABLE 8-2 Common Causative Organisms, Agents, and Conditions Involved in the Etiology of Vulvovaginitis

| ORGANISM/AGENT/CONDITION | EXAMPLES |

|---|---|

| Bacterial vaginosis (BV) | Gardnerella vaginalis, Mycoplasma hominis, other anaerobic microorganisms |

| Vulvovaginal candidiasis (VVC) | Candida albicans, Candida tropicalis, Candida glabrata, other Candida species |

| Trichomoniasis | Trichomoniasis vaginalis |

| Chemical vulvovaginitis | Feminine hygiene products: tampons, sanitary pads, douches, latex condoms, spermicides, colored and perfumed soaps, toilet paper, bubble baths |

| Allergic vulvovaginitis | Latex condoms, topical antifungal agents, and preservatives and other agents in lubricants |

| Atrophic vulvovaginitis | Estrogen deficiency due to menopause, anti-estrogenic therapies, or hormonal dysregulation |

| General causes/factors that might lead to or increase susceptibility to vulvovaginal infection and VVC |

BACTERIAL VAGINOSIS

Bacterial vaginosis (BV) is a common form of infectious vaginitis caused by the polymicrobial proliferation of Gardnerella vaginalis, Mycoplasma hominis, and other anaerobes. It is associated with loss of normal lactobacilli.2 BV accounts for at least 10% and as many as 50% of all cases of infectious vaginitis in women of childbearing age.1,7 Determining the presence of BV can be difficult, however, because as many as 75% of women are asymptomatic.1

Diagnosis

Diagnosis is based on the Amstel criteria, which is considered 90% accurate with three or four of the following findings: the presence of milky, homogenous discharge, vaginal pH greater than 4.5 positive whiff test (“fishy” odor to the vaginal discharge), and the presence of clue cells on light microscopy of vaginal fluid. Odor is a symptom that is frequently associated with BV, due to amines produced from the breakdown products of amino acids produced by Gardnerella vaginalis in the presence of anaerobic bacteria. This also results in a rise in vaginal pH.2

Risks for Developing BV

Numerous factors, described in Table 8-3, are associated with the development of BV. It is uncertain whether BV is a sexually transmitted disease. The prevalence is higher in women with multiple sexual partners and in women seeking the services of STD clinics. Treatment of sexual partners of women with the infection has not definitely proved to be beneficial; however, urethral smears of male partners often show typical BV morphocytes.1,2,5

TABLE 8-3 Factors Associated with the Development and Pathophysiology of Bacterial Vaginosis

| TYPE OF RISK FACTOR | EXAMPLES |

|---|---|

| Personal risk factors |

Risks Associated with BV

BV in pregnancy appears to be a risk factor for second trimester miscarriage, premature rupture of the membrane and premature labor, chorioamnionitis, and post-cesarean and postpartum endometritis.10,11 Women with BV have an increased incidence of abnormal Pap smears, pelvic inflammatory disease (PID), and endometritis. Further, the presence of BV in women undergoing invasive gynecologic procedures may increase the risk of serious infection including vaginal cuff cellulitis, PID, and endometrirtis.1 Eliminating BV appears to decrease the risk of acquiring HIV infection; thus, it is suggested that women with BV be treated regardless of whether they are symptomatic.5

Conventional Treatment of BV

CDC guidelines recommend the treatment of all women with symptomatic BV.5 Conventional treatment of BV is metronidazole (Flagyl) orally or vaginally (Metro-gel), or Clindamycin. Proper treatment typically results in an 80% cure rate at 4 weeks, with recurrence rates of 15% to 50% in 3 months.2 Treatment failure may be caused by lack of successful recolonization of hydrogen peroxide producing strains of lactobacillus, antibiotic resistance, and possibly reinfection by male partners.

Metronidazole is also the prescribed treatment during pregnancy; however, it is contraindicated in the first trimester because of theoretic risks of teratogenicity. Thus, many pregnant women prefer to avoid exposure altogether.10,11 Clindamycin is used as an alternative.1 Evidence on the use of antibiotics in pregnancy to reduce the risk of preterm labor and its associated morbidities is somewhat conflicting. A Cochrane review concluded that no evidence supports the screening of all women for BV, and Guidelines of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) also does not recommend screening in asymptomatic patients.12,13 According to a recent (2005) systematic review, no evidence supports the use of antibiotic treatment for either BV or Trichomonas vaginalis (see later in this section) for reducing preterm birth in low- or high-risk women.14 Nonetheless, CDC Guidelines (2002) still recommend treatment of all pregnant women with Metronidazole or Clindamycin.5

VULVOVAGINAL CANDIDIASIS

Vulvovaginal candidiasis (VVC), commonly referred to as yeast infection, is the second most common cause of vaginitis in the United States. Approximately 75% of all women will experience an episode of VVC in their lifetime, with RVVC occurring in 5% of women.1,3 It is most commonly caused by the fungus Candida albicans; however, other Candida species, such as C. tropicalis and C. glabrata are becoming increasingly common, possibly because of increased use of OTC antifungals, and they are also typically more resistant to antifungal treatments.1 OTC antifungal treatments are among the top 10 selling OTC medications in the United States with an estimated $250 in annual sales.6 Establishing Candida as a cause of vaginitis can be difficult, because 50% of all women have Candida organisms as part of their normal vaginal flora.1 Candida is not considered a sexually transmitted disease, and conventional medical practice does not include treatment of male partners unless uncircumcised or presenting with inflammation of the glans penis.1 RVVC is defined as four or more episodes annually.2 Recurrence may be a result of associated factors, intestinal microorganism reservoir, vaginal persistence, or sexual transmission.1 Genital candidiasis is associated with antibiotic use, oral contraceptives and HRT, and other drugs that change the vaginal environment to favor proliferation of Candida. Vaginal yeast infections are also more common during pregnancy and menstruation, and in diabetics. Drugs and diseases that suppress the immune system can facilitate infection.

Causes and Risk Factors for Developing VVC

Reported risk factors include:

Additional factors may include anything that disrupts the normal balance of vaginal flora, which are listed in Table 8-2.

Diagnosis

Definitive diagnosis of Candida can be based on positive microscopic findings.6 Cultures are expensive, but obtaining a positive fungal culture can be important for the diagnosis and effective treatment of RVVC.6 Candida vaginitis is associated with a normal vaginal pH (≤ 4.5). Identifying Candida by culture in the absence of symptoms is not an indication for treatment, because it is a part of the normal endogenous flora.

Conventional Treatment Approaches of VVC

Uncomplicated VVC is intermittent and infrequent, and in 80% to 90% of cases results in resolution of symptoms and negative culture after a short course of topical azole drugs.5 Examples of azole-containing antifungal creams include: clotrimazole, miconazole, ketoconazole, and fluconazole. These are currently available OTC. The duration of treatment with these preparations may be 1, 3, or 7 days. Alternatively, ketoconazole, fluconazole (Diflucan), itraconazole, or Nystatin can be taken orally. Self-medication with OTC preparations should be advised only for women who have been diagnosed previously with vaginal Candida infection and who have a recurrence of the same symptoms. Any woman whose symptoms persist after using an OTC preparation or who has a recurrence of symptoms within 2 months should seek medical care. Treatment with azoles results in relief of symptoms and negative cultures among 80% to 90% of patients who complete therapy. Topical agents usually are free of systemic side effects, although local burning or irritation may occur. A maximum of 7 days of topical therapy is recommended during pregnancy. Oral agents lead to better compliance but have a greater risk for systemic toxicity, and occasionally may cause nausea, abdominal pain, dizziness, rash, or headaches.15 Therapy with the oral azoles occasionally has been associated with abnormal elevations of liver enzymes. Occasionally, women who take oral contraceptives must stop using them for several months during treatment for vaginal candidiasis because they can worsen the infection. Women who are at unavoidable risk of vaginal candidiasis, such as those who have an impaired immune system or who are taking antibiotics for a long period of time, may need an antifungal drug or other preventive therapy. For women with complicated VVC (RVVC), a longer duration of therapy may be recommended, followed by a 6-month period of maintenance therapy.5 Azole drugs may significantly interact with a number of drugs (e.g., astemizole, cisapride, H1-antihistamines interactions have been associated with cardiac dysrhythmia) owing to potent inhibition of cytochrome P3A4, leading to increased bioavailability of the interacting drug.2

TRICHOMONIASIS

Trichomoniasis vaginalis is a motile, flagellate protozoan. It is the third most common cause of vaginitis. Every year, approximately 180 million women worldwide are diagnosed with this infection annually, accounting for 10% to 25% of all vaginal infections.1 Current belief is that T. vaginalis is almost exclusively acquired through sexual contact.2 Male sexual partners are infected in 30% to 80% of cases.1

Symptoms

Symptomatic infection causes a characteristic frothy green malodorous discharge with a high pH (can be as high as 6.0).5 Additionally, there may be soreness and irritation in and around the vulva and vagina, dysuria, dyspareunia, bleeding upon intercourse, inability to tolerate speculum insertion because of pain, or a superficial rash on the upper thighs with a scalded appearance. The cervix may have a characteristic appearance, called petechial strawberry cervix, in up to 25% of cases.1 Chronic asymptomatic infection can exist for decades in women; an infection also may present atypically.2 In men, infection is mostly asymptomatic, or there may be a thin white or yellow purulent discharge with dysuria (nongonococcal urethritis).2,5

Diagnosis

Trichomoniasis can be diagnosed on the basis of simple microscopy, pH evaluation, and amine tests.2 However, in as many as 50% of cases, microscopy yields negative findings in spite of strong evidence of T. vaginalis infection. In this case, PCR can be used to obtain a definitive diagnosis; however, it is more costly.

Risk Factors Associated with the Development of Trichomoniasis

Smoking, IUD use, and multiple sexual partners all increase the risk of contracting T. vaginalis.1 Statistically, black unmarried women who smoke cigarettes, use illicit drugs, less educated teenagers, and those of low socioeconomic groups are more likely to be colonized with this organism, as are women who have had greater than five sexual partners in the past 5 years, have a history of gonorrhea or other STDs, and who have an early age at first intercourse.

Risks Associated with Trichomoniasis Infection

Trichomoniasis is associated with and may act as a vehicle of transmission for other sexually transmitted diseases, including HIV.1,2,7 It is also associated with an increased risk of premature rupture of the membrane, premature birth, and low birth weight.2,5

Conventional Treatment of Trichomoniasis Infection

CDC treatment guidelines for treatment of T. vaginalis infection is oral metronidazole, which has a cure rate of 90% to 95%. Unlike with other vaginal infections, treatment is recommended regardless of whether a woman is symptomatic.7 Treatment success may be increased with treatment of sexual partners. Sex is to be avoided until the patient and any sexual partners are cured. Follow-up is considered unnecessary in patients who are initially asymptomatic or who become asymptomatic after treatment is completed. Oral metronidazole is recommended for treatment of symptoms in pregnant women.5 Treatment during pregnancy has not been shown to reduce the risk of preterm delivery.7 Also, as stated, physicians and pregnant women may be hesitant to use this drug during pregnancy owing to potential risks of teratogenicity. A recent Cochrane review found no benefit from antimicrobial treatment for T. vaginalis during pregnancy, and in fact, implies possible harm from treatment on the basis that the largest trial was stopped early due to increased risk of preterm labor with metronidazole treatment.14 As this is the only medication used to treat T. vaginalis, hypersensitivity and drug resistance are potential obstacles to therapy. Increasing dosage may overcome resistance, and a desensitization protocol is used in cases of hypersensitivity to the drug.7 Additionally, other drugs are available in Europe but have not yet been approved by the FDA for use in the United States.7

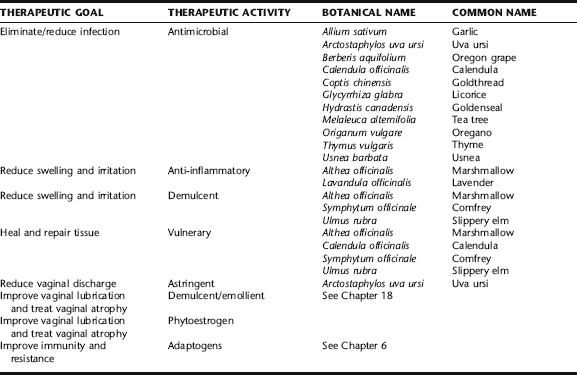

THE BOTANICAL PRACTITIONER’S PERSPECTIVE

Research and clinical experience indicate that women commonly seek OTC and alternative therapies for the treatment of vaginal infections and vulvovaginitis (Table 8-4). In one study, 105 patients, with a mean age of 36 years, and 50% with college degrees, referred by their gynecologists for evaluation of chronic vaginal symptoms, were interviewed about their OTC and alternative medicine use in the preceding year, it was found that 73% of patients had self-treated with OTC antifungal medications or povidone-iodine douching and 42% had tried alternative therapies including acidophilus pills orally (50%) or vaginally (11.4%), yogurt orally (20.5%) or vaginally (18.2%), vinegar douches (13.6%), and boric acid (13.6%).16

Vulvovaginitis may simply be an acute response to a temporary period of imbalance or recent exposure to precipitating factors, such as a period of stress at school or work, excessive consumption of sugar or alcohol at holiday time, or increased sexual activity with condom and spermicide use, affecting proper balance in local flora. In such cases, simple lifestyle modifications combined with topical applications are often adequate treatments. Recurrent vulvovaginitis may be part of a larger picture of chronic lifestyle imbalance, underlying conditions that disrupt the vaginal flora (e.g., bowel dysbiosis or hormonal dysregulation) or exposure to any of the many instigating causes mentioned earlier in this chapter (see Table 8-2). Complicated, recurrent vulvovaginitis can be more difficult to treat but can often be effectively addressed with a combination of local and systemic strategies and removal of underlying causes. Patients with intractable vulvovaginitis should be evaluated for serious underlying conditions such as immunosuppression or diabetes mellitus, and any botanical treatment should occur in conjunction with appropriate medical care. Although there is evidence in the medical literature to suggest that, with the exception of trichomoniasis, it is not necessary to treat sexual partners; empirical evidence from botanical clinical practice suggests that recurrence is less likely when all partners are treated. This should not be surprising, as with most vaginal infections, it has been found that men do harbor organisms in the urethra.

The goal of the botanical practitioner is to reduce or eliminate factors that encourage infection or overgrowth of pathogenic organisms, restore the normal vaginal environment and its flora, and relieve symptoms associated with infection. This chapter does not address hormonal dysregulation that may be associated with vulvovaginitis.

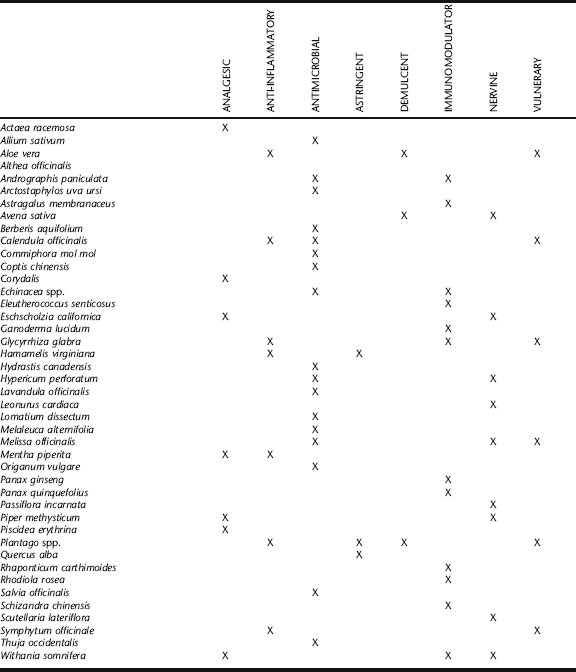

Antimicrobial Therapy

Antimicrobial herbs are used as primary treatments in cases of vulvovaginitis when due to infectious causes. For acute infections, they are generally used solely as topical applications. For recurrent cases, external application is combined with oral use. Internal treatment should focus on immune supporting and antimicrobial botanicals, including echinacea, garlic, goldenseal, Oregon grape root, Pau d’arco, astragalus, and various medicinal mushroom species such as maitake and reishi medicinal mushrooms. Also see Chapter 7 for a discussion on adaptogens and immune support.

Garlic

Garlic is a popular antimicrobial botanical treatment for vaginal infections, effective when applied in fresh whole form. A single clove is carefully peeled and inserted whole at each application, usually at night, and left in during sleep. It is sometimes dipped in a small amount of vegetable oil to ease insertion. It also may be wrapped in a small piece of gauze or with a piece of string with a tail left hanging to ease removal. Otherwise, it can be removed manually. In vitro, garlic has demonstrated antimicrobial effects against a wide range of bacteria and fungi, including E. coli, Proteus, Mycobacterium, and Candida species.17 In a study by Sandhu et al., 61 yeast strains, including 26 strains of C. albicans were isolated from the vaginal, cervix, and oral cavity of patients with vaginitis and were tested against aqueous garlic extracts. Garlic was fungistatic or fungicidal against all but two strains of C. albicans. In another in vitro study, an aqueous garlic extract effective against 22 strains of C. albicans isolated from women with active vaginitis. At body temperature, garlic had mostly fungicidal activity; below body temperature, the action was mostly fungistatic.18,19 Cases of irritation and even chemical burn have been reported after prolonged application of garlic to the skin or mucosa.20

Goldenseal, Goldthread, and Oregon Grape Root

Goldenseal, goldthread, and Oregon grape are all herbs that contain the alkaloid berberine, a major active component possessing antimicrobial activity.21 In vitro studies demonstrate a rational use of the herb for its antibacterial properties.22,23 Berberine has demonstrated specific activity against C. albicans and C. tropicalis as well as to a species of trichomoniasis, T. mentagrophytes, among other pathogens.20,22 These herbs have been used historically and in modern herbal medicine with good reliability for the treatment of a variety of infectious conditions, both internally and topically. Goldenseal is considered by many herbalists to be the most effective of the three herbs. It is commonly included, as is Oregon grape root, as an ingredient in topical preparations for the treatment of vaginitis, added in powder or tincture form to suppositories or powder inserted vaginally in “00” capsules. Internal use of goldenseal, in addition to specific antimicrobial activity, may enhance immune response via stimulation of increased antibody production and may be suggested for oral use in intractable cases.24 Goldthread has demonstrated significant antimicrobial activity against a wide range of Candida species.25

Oral consumption of these herbs is generally contraindicated for use in pregnancy. Goldenseal root is an endangered North American plant. Therefore, only cultivated root should be purchased for use. Oregon grape and goldthread can be substituted with confidence.25

Licorice

Licorice root is one of the most widely used herbs for the treatment of a range of inflammatory conditions. It has demonstrated effectiveness as a demulcent in the treatment of oral, gastric, and respiratory tract conditions, including ulcers and inflammation.20 Although no research was identified on the use of this herb for vulvovaginitis, its effects on other mucosa would seem to substantiate this application. Additionally, licorice alcohol extracts have shown effectiveness against E. coli, and Candida and Trichomoniasis species in vitro. Alcohol extracts can easily be added to suppository blends for topical application.

Oregano and Thyme

The antimicrobial properties of essential oils have been known since antiquity. In vitro testing of essential oils against a wide variety of microorganisms, showed thyme and oregano to possess the strongest antimicrobial properties among many herbs that were tested.26 Thyme essential oil has also found to be specifically effective against Candida spp.27,28 Direct application of undiluted oil (neat oil) is not recommended as it is too caustic to the skin and sensitive mucosa. Rather, a small amount of essential oil can be added to suppository blends, diluted tincture may be added to peri-washes and sitz baths, and tea of these herbs may be used as a base to which other herbs may be added for peri-washes and sitz baths. See sample formulae in this chapter and Chapter 3.

Tea Tree

Tea tree oil (TTO) is derived from the leaves of the tea tree (Fig. 8-1), a native to Australia with a history of use of the leaves for the treatment of colds, coughs, and wounds by indigenous Australians, who spoke of healing lakes in which leaves of the tree had decayed. The medical use of the oil as an antiseptic was first documented in the 1920s, and led to its commercial production, which remained high throughout World War II.29 Legend has it that it was provided to Australian soldiers fighting in World War II for use as an antiseptic and that harvesters were exempt from enlisting.29 Reports of the effectiveness of TTO appeared in the literature from the 1940s through the 1980s, with a significant increasing interest in the medical value of TTO seen in the 1990s to the present, corresponding with interest in CAM generally. Current research, presented in a thorough review by Carson et al., supports its use as an antibacterial and antifungal, as well as an anti-inflammatory.29 Limited studies have been done on TTO’s use as an antiviral, but a few trials have indicated possible activity against enveloped and non-enveloped viruses.29 A broad range of bacteria have demonstrated in vitro susceptibility to TTO, including those known to be associated with BV. A case report in which a woman successfully self-treated with TTO-containing suppositories also supports the use of TTO in BV. 30 31 32 33 34 35 At concentrations lower than 1%, TTO may be bacteriostatic rather than antibacterial.29 Several studies have demonstrated efficacy against C. albicans; however, to date no clinical trials have been done. A rat model of vaginal candidiasis supports the use of TTO for VVC.30 The organisms on which numerous TTO antifungal studies have focused.32, 35 36 37 Two studies demonstrated antiprotozoal activity of TTO, one specifically supporting anecdotal evidence that TTO is effective against T. vaginalis. The mechanisms of antimicrobial action are similar for bacteria and fungi and appear to involve cell membrane disruption with increased permeability to sodium-chloride and loss of intracellular material, inhibition of glucose-dependent respiration, mitochondrial membrane disruption, and inability to maintain homeostasis.33, 38 39 40 Perhaps what has attracted the most interest about this herb is that it has demonstrated activity against antibiotic-resistant bacteria. It has been used in Australia since the 1920s has not led to the development of resistant strains of microorganisms, nor have studies that have attempted to induce resistance with the exception of one case of induced in vitro resistance in Staphylococcus aureus.41,42

Usnea

Usnea lichens (Fig. 8-2) have a history of use that spans centuries and countries from ancient China to modern Turkey, from rural dwellers in South Africa to modern day naturopathic physicians and herbalists in the United States.43,44 The lichen is rich in usnic acid, which has demonstrated in vitro antimicrobial activity against bacteria, viruses, protozoa. Additionally, it exhibits anti-inflammatory and analgesic activity.25 Alcohol extract may be added to a suppository blend or diluted in water or tea (1 tbs tincture/cup of liquid) for use as a peri-wash or in sitz baths.

Uva Ursi

Uva ursi is used by midwives as a topical antiseptic and astringent to relieve vulvar and urethral irritation associated with vulvovaginitis. Leaf preparations have shown antimicrobial activity against C. albicans, S. aureus, E. coli, and other pathogens.20 For vulvovaginitis, it is used topically as a peri-rinse or in sitz baths.

Symptomatic Relief and Tissue Repair

Calendula

Calendula has demonstrated efficacy in the treatment of wounds, promoting tissue regeneration and re-epithelialization, and has also shown some antimicrobial activity (see the preceding). It is soothing as a tea, oil, or diluted tincture (1 tbs tincture to ¼ cup of water), and is an important ingredient in topical vulvovaginitis preparations.45 ESCOP recommends calendula for the treatment of skin and mucosal inflammation and to aid wound healing.46

Comfrey Root

Comfrey root (Fig. 8-3) has a very long history of folk use for healing damaged skin, tissue, and broken bones. It is highly mucilaginous. It is thought that allantoin and rosmarinic acid are the constituents mainly responsible for comfrey’s healing and anti-inflammatory actions.47 Comfrey is indicated for topical use only. Use on broken skin or mucosa should be minimized but is reasonable for short durations (1 to 2 weeks at a time), and should not exceed 100 µg of pyrrolizidine alkaloids with 1,2 unsaturated necine structure daily for a maximum of to 4 to 6 weeks annually.48 Comfrey infusion may be added to a peri-rinse or sitz-bath blend, or comfrey oil or finely powdered herb may be added to a suppository blend.

Lavender

Lavender has a folk tradition of use for topical treatment of mild wounds, for which it is still included by herbalists and midwives in topical preparations for vulvovaginitis.47 Additionally, its fragrance imparts a pleasant scent to herbal preparations. It may be used as a rinse or sitz bath in tea form or using diluted tincture, or several drops of essential oil may be added to rinses, sitz baths, or suppositories.

Marshmallow Root

Marshmallow is demulcent and vulnerary. Marshmallow root contains a mucilage that covers the mucosa, protecting it from local irritation.46 Topical application is soothing in sitz baths and peri-rinses, and the powdered herb, finely ground, helps give herbal suppositories firmness. Slippery elm bark powder can be substituted for marshmallow root powder in suppository blends.

Topical Preparations for Treating Vulvovaginitis

Sitz Baths, Peri-Washes, and Suppositories

The most common forms of topical applications used in the treatment of vulvovaginitis are sitz baths, peri-washes, and suppositories. Instructions for each of these preparations are found in Chapter 3.

Suppositories are applied nightly for 7 to 14 days. It is advisable to wear a light pad and old underwear while sleeping because the suppository will melt at body temperature. The oils and herbs may stain bedding or clothes.

Why Douching Is Not Recommended

Women commonly douche because of the misperception that it “cleans out” the vaginal canal and can thus cure vaginal infections. A systematic review found that although douching may provide some symptomatic relief and initial reduction in infection, it may lead to rebound effects and other complications in the long run. Povidone iodine preparations, a common OTC choice for self-treatment, have been demonstrated to cause a “rebound effect” in which a higher than normal bacterial colonization is seen within weeks of last douching, which could actually increase the risk of bacterial vaginosis. Routine douching for hygiene has been shown to double the risk of acquiring vaginitis. Douching of all types can lead to increased risks of PID, endometritis, salpingitis, and ectopic pregnancy.19

CHRONIC VULVOVAGINITIS AND INTESTINAL PERMEABILITY

Nutritional Considerations: Lactobacillus/Yogurt

The goal of treatment with lactobacillus supplements or yogurt, taken orally or applied vaginally, is recolonization of the vagina (and bowel with oral intake) with adequate numbers of healthy flora capable of controlling and resisting pathogenic infection. The success of this treatment requires products that contain the proper lactobacillus species and that these species be active. Additionally, oral yogurt therapy requires the survival of lactobacilli through the GI system and digestive processes, as it is thought that vaginal recolonization occurs as a result of migration of the microorganisms from the anus to the vaginal introitus.19 Effective oral and topical yogurt therapy also requires that the lactobacilli be able to adhere to the vaginal epithelium. L. acidophilus is poorly adherent to the vaginal walls, and it also is not a major rectovaginal species. Although two clinical trials have demonstrated significant efficacy with oral and/or topical use, the use of other species of lactobacillus, such as L. crispatus, L. jensenii, L. rhamnosus, and L. fermentum, may be more effective.20,49 A randomized crossover study with a washout period by Shalev et al. studied the effects of oral yogurt prophylaxis on a group of women (n = 46) with BV (n = 20) and candidal vaginitis (n = 18) or both (n = 8). The study showed a significant decrease in BV and no significant decrease in candidal infection. Only 28 participants were still enrolled in the study at 4 months and only 7 completed the protocol.51 In an open crossover trial by Hilton et al., a randomized group of women (n = 33) with RVVC were assigned to either a 6-month protocol of daily oral intake of L. acidophilus containing yogurt or a yogurt-free diet. A threefold decrease was seen in candidal infections, substantiated by wet mount and potassium hydroxide. Interestingly, although only 13 women completed the yogurt treatment, 8 women in the yogurt arm refused to switch over to the yogurt-free diet.51 Patients with lactose intolerance may experience GI complaints from oral yogurt intake. Topical treatment of BV with yogurt has been evaluated in several studies. In an unblinded study of 84 pregnant women with BV a program of yogurt douching twice daily for 7 days (n = 32) compared with acetic acid tampons (n = 20) or no treatment (n = 20), it was found after 2 months of treatment 88% of women in the yogurt group and 38% of women in the acetic acid group compared with 5% of women in the no treatment group were BV free. A multicenter, placebo-controlled RCT looking at the effects of lactobacillus vaginal tablets combined with estrogen as a delivery agent on BV demonstrated a 75% cure rate at 2 weeks and an 88% cure rate at 4 weeks compared with a 25% and 22% respective cure rates at corresponding times in the placebo group.19

Empiric evidence from herbal and midwifery practice suggests that live active culture yogurt may be more effective than acidophilus tablets or capsules, although any of the options is potentially effective. It is also provides some immediate relief of burning and itching to inflamed tissue. The easiest way to apply it is in the shower, placing one foot on the edge of the tub and using two fingers to insert the yogurt vaginally and around the vulva. Do not place fingers back in the yogurt after applying; rather place the appropriate amount (2 to 3 tbs) in a small container. The yogurt should be left on for 3 to 5 minutes, and then rinsed off, repeating up to two times daily depending upon the severity of the infection and irritation. Repeat for up to 2 weeks, although treatment is often effective within several days.

Additional Therapies

Boric Acid

Boric acid is a common OTC treatment for VVC and RVVC that is both self-prescribed and recommended by health practitioners.1,19,52 Although it has not been widely studied, four studies have shown positive outcomes, even compared with conventional antifungal therapy, and it is considered an effective therapy for the treatment of vaginal candidiasis.1,18,19,52,53 In one study, 92 women with chronic mycotic vaginal infections were followed with microscopic examination of the vaginal discharge during prolonged therapy with antifungal agents and boric acid. A microscopic picture unique to chronic mycotic vaginitis was observed, representing the cytologic reaction of the mucous membrane to chronic yeast infection. This diagnostic tool proved extremely effective in detecting both symptomatic and residual, subclinical mycotic infection and provided a highly predictive measure of the probability of relapse. The ineffectiveness of conventional antifungal agents appeared to be the main reason for chronic mycotic infections. In contrast, boric acid was effective in curing 98% of the patients who had previously failed to respond to the most commonly used antifungal agents and was clearly indicated as the treatment of choice for prophylaxis.53 In a double-blinded, randomized study, 108 VVC-positive college students used boric acid or Nystatin capsules once daily for 2 weeks. Boric acid cure rates were 92% at 7 to 10 days posttreatment and 72% at 30 days, a statistically significant improvement over the Nystatin capsules, which only had a cure rate of 64% at 7 to 10 days posttreatment, and 50% at 30 days posttreatment.54 In a case series of 40 patients with vulvovaginitis, 95% of patients remained symptom-free at 30 days post–boric acid treatment, and in another study, boric acid was tested against an azole-resistant strain of yeast, more commonly seen in women with recurrent yeast infections and yielded clinical improvement occurred in 81% of cases, with mycological eradication in 77% of the women.19,55,56 The standard recommended dose and application is 600 mg of boric acid placed in a size “0” gelatin capsule and inserted vaginally. For acute treatment, one capsule is inserted nightly for 14 days, followed by a maintenance treatment of twice weekly insertion.19,53 Some women report mild to moderate burning as the capsule dissolves. If intercourse occurs during the treatment period, males may report dyspareunia.19 Serious side effects have not been reported from treatment.53 Boric acid, available in drug stores, can be considered a safe, effective, accessible, and affordable treatment for vaginal candidiasis.

General Suggestions

Reducing exposure to the personal, sexual, chemical, and allergenic factors described in the preceding can be beneficial in preventing and reducing vulvovaginitis and infection. Wearing clean cotton underwear or “breathable” fabrics, changing underwear more often if there is copious vaginal discharge or dampness, sleeping without underwear, wearing loose-fitting pants, and observing hand-washing before and after genital contact may reduce the incidence and frequency of vulvovaginitis.52 Wearing a thong may cause irritation or facilitate the transmission of anorectal organism to the vulvovaginal area. Regular bathing and showering with gentle soap, keeping the vulvar area dry, and regular use of sitz baths also may be helpful, the latter particularly in candidal vulvovaginitis.

TREATMENT SUMMARY FOR VULVOVAGINITIS

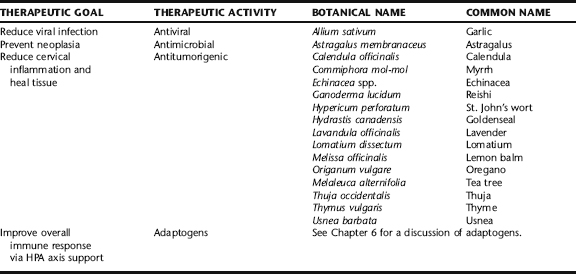

GENITAL WARTS (CONDYLOMA AND HPV)

It is suspected that HPV remains dormant in the body once contracted; therefore, the goal of treatment is to minimize visible lesions and prevent progression to neoplasia, rather than eradicate the virus.52

DIAGNOSIS

Although there are HPV nucleic acid tests available to identify the viral type, these tests are not routinely ordered. There are, in fact, no data that support the use of type-specific HPV nucleic acid tests in the routine diagnosis or management of genital warts.57 The HPV nucleic acid tests are available primarily for research purposes and to determine possible risk for carcinoma in high-risk individuals.

CONVENTIONAL TREATMENT APPROACHES

Determination of the type of treatment is made after evaluation of wart size, location, morphology, patient preference, cost of treatment, adverse effects, and provider preference. Generally, a course of applied treatments is required to remove genital warts. First-line therapy for HPV may consist of the application of 0.5% podophyllotoxin (Podofilox 0.5% solution or gel) one to four times. Podophyllotoxin is an antimitotic agent. This treatment has been shown to be effective in 70% to 90% of men or women with exposed and accessible genital warts.58,59 This treatment is typically well tolerated and self-administered, and produces minimal local irritation. Ten to twenty percent podophyllin resin ethanolic solution has also been used topically. However, podophyllin resin is less effective than podophyllotoxin. In one study, 94% of patients treated with podophyllotoxin were cured versus only 29% of patients treated with podophyllin resin.59 Additionally podophyllin resin is commonly associated with local inflammation, erosion, pain, and burning. Finally, concern exists about the systemic absorption of the podophyllin resin and its systemic toxicity, particularly in pregnant women.

Cryotherapy is another common treatment for exposed genital warts. Cryotherapy with liquid nitrogen or cryoprobe is typically done weekly or biweekly. Cryotherapy causes thermal-induced cytolysis. This therapy can be quite effective if applied properly; however, overtreatment can cause localized pain and blistering. Conversely, undertreatment is ineffective. Typical second-line therapeutic interventions include surgical removal of warts. There are several techniques of surgical removal. All techniques require local anesthesia. Surgical removal is a one-time treatment. However, surgery is more expensive and requires more time than medical treatment options. Surgical treatment of genital warts is usually reserved for patients with a large number of lesions or for patients who have not responded to other treatments. Another second-line therapy is the intralesional injection of interferon. Many trials have confirmed the efficacy of this treatment. It causes the disappearance of all visible warts in approximately 43% of patients and visibly shrinks visible warts in an additional 25%.60 However, interferon therapy is expensive and requires three treatments each week, usually for 4 to 6 weeks.

THE BOTANICAL PRACTITIONER’S PERSPECTIVE

The herbalist’s approach to genital warts may be in conjunction with or in place of conventional treatment. A comprehensive botanical approach supports the body’s inherent abilities to resist infection and uncontrolled cellular proliferation caused by the virus. Herbs with antiviral actions are key components of the botanical protocol. Herbs with immunostimulatory actions, particularly activation of cell-mediated immunity, are of specific importance. Adaptogens (see Chapter 6) are also ideally included in a comprehensive botanical protocol to further support the immune system.

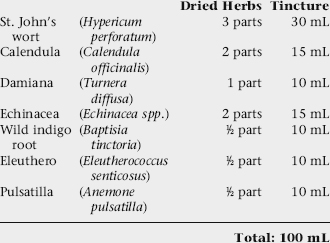

DISCUSSION OF BOTANICAL PROTOCOL

Protocol for the Treatment of HPV

Topical Treatment

| Thyme | (Thymus vulgaris) | 30 mL |

| Goldenseal | (Hydrastis canadensis) | 30 mL |

| Myrrh | (Commiphora mol mol) | 20 mL |

| St. John’s wort | (Hypericum perforatum) | 20 mL |

| Thuja | (Thuja occidentalis) | 10 mL |

| Total: 100 mL | ||

| Tea tree | (Melaleuca alternifolia) | 30 mL |

| Goldenseal | (Hydrastis canadensis) | 30 mL |

| Oregano | (Origanum vulgare) | 20 mL |

| Lemon balm | (Melissa officinalis) | 20 mL |

| Licorice | (Glycyrrhiza glabra) | 10 mL |

| Total: 100 mL | ||

Option 3. For suppositories, use either combination of the above tincture combinations in a suppository recipe. See Chapter 3 for general suppository instructions.

Combine external treatment with:

Antiviral Tincture: Internal Treatment

Combine the following tinctures:

| Astragalus | (Astragalus membranceus) | 25 mL |

| Reishi | (Ganoderma lucidum) | 25 mL |

| Ashwagandha | (Withania somnifera) | 25 mL |

| Echinacea | (Echinacea spp.) | 15 mL |

| Usnea | (Usnea barbata) | 10 mL |

| Total: 100 mL | ||

6 to 12 weeks, as needed. Suppositories can be inserted vaginally or rectally for warts in those areas. They should be inserted nightly five times per week for 6 to 12 weeks. The patient should be re-evaluated periodically for HPV.

Astragalus

Astragalus has been used for centuries in Chinese medicine as a qi tonic, specifically for strengthening what is called the “wei qi” or the protective energy of the body. It has long been used to build energy, increase general immunity, improve digestion and improve longevity. Herbalists and naturopathic doctors commonly use astragalus for its immunostimulatory effects. Oral doses of astragalus have been found to increase IgE, IgA, and IgM antibody levels and lymphocyte levels in humans.61 Of particular relevance to the treatment of genital warts was a randomized, controlled trial involving 531 patients with chronic cervicitis secondary to HPV, CMV, and HSV infections. This trial demonstrated that a liquid extract of astragalus root potentiated recombinant interferon in the treatment of cervicitis, particularly when resulting from HPV infection.62 In addition to the immunostimulatory effect of astragalus, people who take it often experience increased physical stamina, increased mental alertness, and decreased fatigue.

Echinacea

The purified polysaccharide, arabinogalactan from E. purpurea, has been found to increase T-cell proliferation and the production of interferon by macrophages.63 Additionally, unpurified fresh pressed juice of E. purpurea has been shown in vitro to induce macrophages to produce cytokines, which in turn create an antiviral effect against viruses, including the herpes virus. Clinical trials of echinacea are of mixed results. As an example, a yearlong prospective, double-blind, placebo-controlled crossover trial (n = 50) examined the efficacy of a tablet form of Echinacea purpurea (Echinaforce) in the clinical course of genital herpes. The study found no statistically significant benefit in the clinical course of frequently recurrent genital herpes.64 It is possible that this study failed to show benefit because of insufficient dosing and/or the use of a tablet form of echinacea. Certain constituents in echinacea species, namely alkenes and amides, possess potent antiviral activity (including against HSV). Ethanol extracts of these constituents and these extracts of echinacea have been shown to have the most potent antiviral activity.65 Although clinical trials have not yet conclusively demonstrated significant antiviral and immune stimulation, previous and current naturopathic and herbal practice demonstrate these effects and hence many modern herbalists and naturopathic doctors use echinacea as part of their treatment of HPV.

Lemon Balm

Acutely, lemon balm extract is applied topically for its virostatic action. Lemon balm has demonstrated effects against a number of viruses including HSV and Influenza. Virostatic effects are attributable to the glycoside-bound phenolcarboxylic acid and its polymers. These constituents block cellular receptors responsible for viral adsorption, and thus viral replication.66 Additionally oxidation products of caffeic acid, found in lemon balm, inhibit protein biosynthesis in vitro, which may account for the antiviral activity of topical application.67 These in vitro data have been confirmed in at least three human trials. One of the more recent trials was a prospective, double-blind, randomized trial (n = 66). The treatment group applied a standardized balm cream [1% Lo-701 dried extract from Melissa officinalis L. leaves (70:1)] four times daily to an active Herpes labialis lesion over a 5-day period. All patients suffered from recurrent Herpes labialis. However, there was a significant decrease in the intensity of herpetic symptoms by day 2 of treatment between the active vs. the placebo group (p = 0.042).68 Lemon balm also has anxiolytic and sedative actions.69

Oregano and Thyme

Both oregano and thyme essential oils are regularly included in vaginal suppositories for the treatment of vaginal infections, including HPV infection. One study reports on the efficacy of thyme as an antibacterial, and in another study oregano and clove oils were diluted and examined for their activity against enveloped and nonenveloped RNA and DNA viruses. Olive oil was also included as a control. Viruses were incubated with oil dilutions and enumerated by plaque assay. Antiviral activity of oregano and clove oils was demonstrated on two enveloped viruses of both the DNA and RNA types and the disintegration of virus envelope was visualized by negative staining using transmission electron microscopy.70,71 Care should be taken in the use of essential oils topically; used undiluted (neat) they can be irritating to sensitive tissues such as cervical or vaginal mucosa. Tincture may be applied directly.

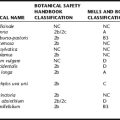

Thuja

Thuja (Fig. 8-4) is used for the treatment of genital and anal warts, and is commonly recommended in the naturopathic treatment of cervical dysplasia for its antiviral activity.72 The main constituent is an essential oil consisting of α-thujone and β-thujone, the content of which varies proportionally with the amount of ethanol used in producing the plant extract. If consumed internally, thujone can be neurotoxic, convulsant, and hallucinogenic. Long-term or excessive use of thujone-rich products can cause restlessness, vomiting, vertigo, tremors, renal damage, and convulsions.73 Internal use of thuja decoctions and even very small doses of thuja oil (e.g., 20 drops per day for 5 days) as an abortifacient has been associated with neurotoxicity, convulsions, and death.72 Additionally, thuja is associated with a substantial risk of inducing fetal malformation, and is absolutely contraindicated for use in pregnancy.72 No research on the short- or long-term topical use of this herb was identified. Ingestion of thuja cannot be recommended because of its significant potential for toxicity.

Usnea

Usnea lichens have a history of use that spans centuries and countries from ancient China to modern Turkey, from rural dwellers in South Africa to modern-day naturopathic physicians and herbalists in the United States.43,44 The lichen is rich in usnic acid, which has demonstrated in vitro antimicrobial activity against bacteria, viruses, and protozoa. Additionally, it exhibits anti-inflammatory and analgesic activity.25 Alcohol extract may be added to a suppository blend or diluted in water or tea (1 tbs tincture/cup of liquid) for use as a peri-wash or in sitz baths.

NUTRITIONAL CONSIDERATIONS

The nutritional supplements recommended in Chapter 7 are appropriate for use when treating HPV infection.

TREATMENT SUMMARY FOR CONDYLOMATA

HERPES

Approximately 75% of individuals in the United States are infected with HSV-1, and about 25% with HSV-2, with an estimated incidence of 500,000 to 1 million new cases annually. 74 75 76 Independent predictors of HSV-2 infection include sex (women are more likely to become infected and have more frequent outbreaks, whereas men are more likely to transmit infection), race (rates are higher among African Americans and Mexican Americans), increased age, less education, poverty, cocaine use, and multiple sexual partners.74 Since the late 1970s, seroprevalence has quintupled among white teenagers and doubled among whites in their twenties. The virus is spread through contact with the lesions and through viral shedding. Sexual contact is the primary method of contamination; however, kissing and other contact with sores or shed virus in an asymptomatic individual can lead to infection. Casual contact, such as sharing of a drinking glass or cigarette has also been known to lead to infection. Ninety percent of affected individuals are unaware they have herpes.77 HSV-2 infection significantly increases susceptibility to HIV infection.

Immunologic changes of pregnancy, particularly depression of T-cell response, appear to make pregnant women more susceptible to a number of viral infections, including HSV.78 Primary herpes outbreaks in pregnancy, especially during the third trimester, pose great danger to a newborn, causing significant morbidity and mortality. Antibodies to HSV-2 have been detected in about 20% of pregnant women, with only about 5% aware they have herpes (see Herpes Simplex Virus in Pregnancy).

Prevention is always the best treatment. Practicing safe sex on all occasions regardless of whether lesions are visible, and avoiding contact with active lesions is essential. HSV may be shed in the saliva and genital secretions of asymptomatic individuals. Active lesions shed between 100 and 1000 times the amount of virus. Minor injury, for example, irritation from vaginal Candida infection, may increase the likelihood of viral transmission. Condoms do not guarantee protection, but do significantly reduce HSV-2 transmission, especially to women.79 The virus is commonly passed from a person who does not know they have the virus because they have never had any symptoms.

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

HSV travels along the peripheral nerve axons to the nerve cell bodies in the dorsal root ganglia and can exist in the paraspinous ganglia indefinitely, sometimes in a completely inactive state. The virus can be reactivated and begin replicating in response to such factors as stress, depression, and anxiety, trauma to mucosa, fever, exposure to ultraviolet light (sun exposure), menstruation, poor sleep, spicy food, immunodeficiency, and other unknown factors. Migration to mucosal surfaces by way of the peripheral sensory nerves can lead to a cutaneous outbreak of lesions, which are often painful. Although the virus usually becomes dormant after an outbreak and before the next outbreak, if it occurs, an infected person, even if asymptomatic, can still pass the virus to another person. Asymptomatic viral “shedding” is common and occurs in cycles. Therefore, transmission of infection is possible at any time regardless of the presence of active lesions. The possibility of transmission between an infected and uninfected person in a monogamous relationship increases at the rate of about 10% a year. Women who have regular herpes outbreaks, or who have a sexual partner who has active outbreaks, should have routine Pap smears because herpes may predispose women to cervical cancer. Recent research suggests possible long-term consequences of harboring chronic HSV infection, such as development of rheumatoid arthritis.80

SYMPTOMS

The first episode of herpes after initial infection is known as the primary outbreak, characteristically appearing with flu-like symptoms such as fever, headache, and swollen lymph glands in the groin (Table 8-6). Primary outbreaks can last 2 to 3 weeks and can be severe enough in rare cases to require hospitalization. Recurrent herpes outbreaks are commonly heralded by a prodromal stage with characteristic feelings of tingling or itching in the genital area or around the mouth, pain and tingling in the groin, and possibly in the buttocks and backs of the thighs. Virus is already present on the skin in the prodromal phase, so this is considered a contagious phase although blisters are not yet visible. The prodromal phase typically lasts 1 to 3 days followed by vesicles, lesions, and scabbing lasting for up to 10 days before complete healing has occurred. Recurrent outbreaks are often mild and may present with pruritus, local tingling or pain, slight vaginal discharge but present with no generalized systemic symptoms. Small sores or vesicles can occur anywhere on the skin or mucous membranes of the mouth anogenital region, and are most common around the mouth and genital area. The vesicles break and become wet, finally crusting over. Healing is complete when new skin is formed under the scab, which falls off. Rarely, focal necrosis, ballooning degeneration of skin cells, and other histopathologic changes can result.

Adapted from Roe V: Living with genital herpes: how effective is antiviral therapy? J Perinat Neonat Nurs 18(3):206-215, 2004.

Most patients are mistakenly thought to be silent carriers. At least 90% of HSV-2 carriers are ignorant of their conditions with up to 60% to 75% having unrecognized signs and symptoms of genital herpes. Commonly, symptoms are falsely attributed to other more casual urogenital problems. Because herpes is a self-healing condition, with symptoms easily controlled with topical nonspecific agents, the diagnosis is not frequently made. The following are examples of the conditions to which female patients attribute what are actually symptoms of genital herpes outbreaks:81

DIAGNOSIS

When a patient presents with clusters of painful vesicles and inflammation of the surrounding area, herpes should be considered. The standard test for HSV infections is viral culture of vesicular fluid. Direct immunofluorescent staining with conjugated monoclonal antibodies to HSV is faster, more expensive, and only about 80% to 90% as accurate as viral culture. Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) is the most accurate and most expensive test.82

Diagnosis in the neonate can be difficult at first because symptoms are sometimes nonspecific (e.g., fever, lethargy), with no other outward signs of infection. Less than 50% of newborns with disseminated disease or encephalitis have skin lesions.83 If diagnosis is delayed, damage to the CNS or internal organs can be significant.

CONVENTIONAL TREATMENT APPROACHES

Antiviral therapy with drugs that selectively inhibit viral replication including acyclovir, famciclovir (Famvir), and valacyclovir (Valtrex) is the standard treatment. Acyclovir has been on the market for over 20 years, and has a reasonable safety profile, even when given during pregnancy. Teratogenicity has not been demonstrated, even during the first trimester. Famciclovir and valacyclovir are more absorbable and higher blood levels can be sustained, although their safety, especially during pregnancy, has not been as thoroughly tested as acyclovir.76 Studies suggest that prophylactic administration of acyclovir during pregnancy can reduce shedding, shorten the duration of shedding, and reduce the cesarean rate, although these were small and not conclusive. The usual dose of acyclovir is 60 mg per kg of body weight per day in three doses intravenously for 14 days for localized skin disease, and 21 days for more severe infections.84 Acyclovir has been associated with numerous side effects in its various dosage forms, including nausea and vomiting, diarrhea, headache, dizziness, fatigue, skin rash, edema, inguinal lymphadenopathy, anorexia, leg pain, medication taste, and sore throat from short-term oral administration, and nausea and vomiting, diarrhea, headache, dizziness, insomnia, irritability, depression, rash, acne, hair loss, arthralgia, fever, palpitations, sore throat, muscle cramps, menstrual abnormalities, and lymphadenopathy with long-term use.

HERPES SIMPLEX VIRUS IN PREGNANCY

Primary herpes infection in pregnancy is associated with miscarriage, premature labor, intrauterine growth retardation, and neonatal infection. Neonatal infection most frequently occurs during labor and is associated with increased neonatal death, brain damage, seizures, cerebral palsy, blindness, and deafness.85 Neonatal herpes affects about 1 in 15,000 newborns and the prognosis for disseminated disease with encephalitis is poor.86 Because 90% of cases of neonatal herpes are a result of direct contact with lesions in the birth canal, cesarean section is routinely performed as the mode of delivery in active herpes outbreaks at the time of labor. Neonates are treated acyclovir or vidarabine, but this treatment is less effective once the infection has spread to the brain and internal organs.87

More recently, experiments have looked at using acyclovir for herpes prophylaxis in late pregnancy. Treatment has been shown to reduce recurrences after a primary infection, and reduce asymptomatic viral shedding as well as need for cesarean delivery; however, prophylaxis only partly prevents neonatal herpes infection, because it is not applicable to patients with no known clinical history but may excrete the virus.86,88

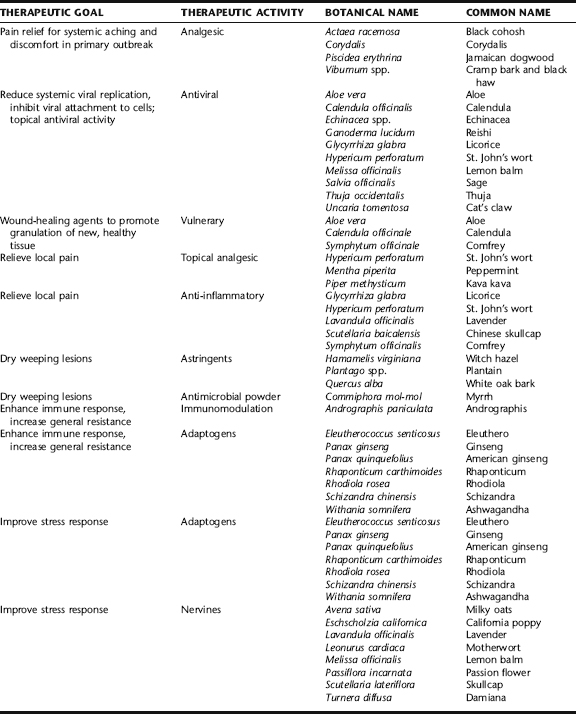

THE BOTANICAL PRACTITIONER’S PERSPECTIVE

HSV infection is a major global health problem, and its association with HIV infection makes it imperative to develop effective prevention and treatment strategies. The efficacy of many topical pharmaceutical agents in treating herpes has been somewhat disappointing and inconsistent, and additionally, are costly.89,90 Patients are often looking for safe and effective alternative measures to reduce the frequency of outbreaks and shorten their duration. It is also important to look for agents that will be effective at preventing the virus from inculcating into nerve cell bodies, proliferating, and taking up host residence. Botanicals represent a promising area for research.16 Unfortunately, at present there are few well-designed human clinical trials looking at the effects of herbs on HSV. However a number of botanicals have demonstrated antiherpetic activity in vitro, offering some validation of the traditional use of herbs for infection. Several herbs have been shown to be topically healing for wounds, and as discussed in Chapter 7, have demonstrated efficacy in improving immune response and reducing stress. These latter categories are listed in Table 8-7 with brief descriptions of their applications to HSV treatment, but discussions of these herbs are found elsewhere throughout this book.

Clinically, patients using a combination of botanical and nutritional therapies report reduced frequency, severity, and length of outbreaks. Herbalists have found botanical medicines effective at relieving symptoms associated with outbreaks, preventing outbreaks, and reducing the frequency of outbreaks (Table 8-7). Some patients have reported going 10 years or more without an outbreak, even with a history or regularly recurrent outbreaks. Similarly, pregnant women have been shown to cease to have recurrent outbreaks during gestation, even with a history of regular recurrence in prior pregnancies (see Case History: Herpes Genitalis). It is unknown how botanicals affect asymptomatic shedding.

Symptomatic relief can be directed at systemic manifestations during a primary outbreak, mostly via analgesics to relieve discomfort and antivirals to control the degree of infection, and can be used topically to speed the healing of lesions and relieve discomfort associated with both primary and recurrent episodes. A number of herbs have been shown to have beneficial effects in supporting and enhancing immunity. Because host immune response plays a role in the outcome of herpes infection, with the immune system modulating infection both in the nervous system and the periphery, prevention focuses on supporting optimal immune response using adaptogens and the use of antivirals to reduce viral attachment and proliferation.91 Additionally, herbs that improve the stress response (adaptogens) and relieve stress (nervines) are important, because stress is both a known precipitating factor for outbreaks and suppressive of immune function (see Chapter 6).

Analgesics

Analgesic herbs are used internally, typically as tinctures, either singly or in combination, for the symptomatic relief of generalized discomfort and aches in uncomplicated primary herpes outbreaks and for aching discomfort in the prodromal phase of recurrent outbreaks. Black cohosh, an antispasmodic and mild analgesic, was historically used specifically for aching, drawing discomfort in the buttocks and the backs of the thighs.92 Cramp bark and black haw are reliable antispasmodic herbs with analgesic effects. Corydalis and Jamaican dogwood have strong analgesic and sedating effects. See Plant Profiles: Black cohosh, for safety considerations.

Antiviral Botanicals

Aloe

Aloe has long been used by herbalists as a topical healing agent for wounds, burns, irritated skin, and sores. Two studies were conducted by Syed et al. examining the efficacy of topical aloe vera treatments on men experiencing primary outbreaks of genital herpes. In the first study, 120 men were randomized into three parallel groups receiving either 0.5% in hydrophilic cream, aloe vera gel, or placebo three times daily for 2 weeks. The shortest mean duration of healing occurred with aloe vera cream, followed by gel and then placebo with healing times of 4.8 days, 7.0 days, and 14.0 days, respectively. Percentages of cured patients were 70%, 45%, and 7.5%, respectively.93 In the second study, 60 men were randomized into two groups receiving 0.5% aloe vera extract in a hydrophilic cream base or placebo. The trial had comparable favorable results to the previously discussed trial.94 Additionally, in vitro testing has demonstrated virucidal effects of anthraquinones and anthraquinone derivatives such as emodin, a component of aloe.

Cat’s Claw

The use of cat’s claw, una de gato, by traditional healers of tropical South America extends back in history for an unknown length of time as part of oral tradition, where it was used to treat gastric ulcers, as an anti-inflammatory, antitumor, and antirheumatic, among other uses ranging from fevers and diarrhea to contraception and female genitourinary cancers. It is also used in the treatment of disharmony between body and spirit, or what we might call anxiety.20 Inhibition of HSV-1 and -2 was demonstrated in vitro by a standardized extract of cat’s claw. H. genitalis was significantly more susceptible to inactivation by the extract than H. labialis.20 Cat’s claw appears to selectively modulate ovarian hormone function and therefore should be used with care in women with hormonal dysregulation, particularly progesterone insufficiency. It is completely contraindicated in pregnancy.20 The herb has demonstrated significant in vitro and in vivo immunostimulatory, immunoregulatory, and immunosuppressive, and anti-inflammatory effects, specifically, enhanced lymphocyte production and inhibition of tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α) in a dose-dependent manner.20 Therefore, it is cautioned any patients on immunomodulating therapies (e.g., immunosuppressant, hyperimmunoglobulin therapy, receiving vaccinations) avoid the use of cat’s claw and caution be exercised in patients with autoimmune conditions. Use of cat’s claw containing products is entirely contraindicated during pregnancy and lactation; however, it has been used traditionally in the immediate postpartum period for recovery after childbirth, and may facilitate milk supply through estrogen modulation.20

Echinacea

Echinacea is a popular herb used to prevent and mitigate viral infections, and also to prevent recurrent infection. It is commonly used as a tincture or decoction as part of a protocol for HSV infection. Midwives rely on it in pregnancy as one of the antivirals considered safe to use during that time. In a 5-month uncontrolled clinical study of 4598 patients, a salve prepared from the juice of the aerial portion of Echinacea purpurea was reported to have an 85% success rate in the treatment of a number of inflammatory skin conditions, among them Herpes simplex eruptions.20 Echinacea is used by herbalists during pregnancy for the prevention of herpes outbreaks. Longitudinal use of echinacea in pregnancy was evaluated for safety and outcomes by Gallo et al. In a prospective study, 206 Canadian women, already taking echinacea-containing products, were compared with a matched cohort not taking echinacea. The products mostly contained E. angustifolia and E. purpurea, although one respondent took E. pallida. Thirty-eight percent took the tincture at a dose of up to 30 drops daily and 58% took tablets or capsules at a dose of 250 to 1000 mg/day. Echinacea use was primarily in the first trimester (54%); 8% used echinacea during all three trimesters. There were no statistical differences between pregnancy outcomes in the two groups nor were there statistically significant differences in the neonates.95

Lemon Balm

Lemon balm (Fig. 8-5) has classically been used as an uplifting herb for the treatment of stress and anxiety. Rich in volatile oils, in vitro and clinical research conducted over the past decade has demonstrated impressive results using lemon balm ointment as a local therapy in the treatment and prevention of herpes outbreaks.46,96,98 In one study, four different concentrations of volatile oils extracted from lemon balm were examined for the effects against HSV-2. At concentrations of 200 µg/mL, replication of HSV-2 was inhibited, indicating that the M. officinalis L. extract contains an anti-HSV-2 substance.96 Another study, a double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomized trial, was carried out with the aim of proving efficacy of standardized and highly concentrated lemon balm cream for the therapy of herpes simplex labialis. Sixty-six patients with a history of recurrent herpes labialis (at least four episodes per year) in one center were treated topically; 34 of them with lemon balm cream and 32 with placebo. The cream had to be smeared on the affected area four times daily over 5 days. A combined symptom score of the values for complaints, size of affected area, and blisters at day 2 of therapy was formed as the primary target parameter. A significant difference seen in the combined symptom score on the second day of treatment is of particular importance because symptoms are usually worst at that time. In addition to reducing the duration of the healing period, the treatment led to prevention of spreading of the infection and had a rapid effect on common herpes symptoms including itching, tingling, burning, stabbing, swelling, tautness, and erythema. Some indication exists that the intervals between the periods with herpes might be prolonged with balm mint cream treatment. There is little reason to expect the development of resistance to treatment.98 Commercial lemon balm extract concentrated creams for topical use are available over the counter and in herbal pharmacies.

Licorice

Numerous in vitro and in vivo studies have shown licorice preparations to have antiviral, antiherpetic, anti-inflammatory, antiulcer, anticarcinogenic, and a wide variety of immunomodulating effects.99,100 Licorice root (Fig. 8-6) is taken singly or in combination as a tea, tincture, or powdered extract in capsules or tablets. It is also applied topically for local relief of swelling and irritation. The herb is indispensable for its inhibitory effects on the virus, its anti-inflammatory effects to reduce pain and swelling of lesions, and its immunomodulatory effects to enhance host resistance and reduce episodes of active lesions.101 Glycyrrhizic acid has demonstrated lipoxygenase, cyclooxygenase, and protein kinase C inhibition. Active fractions include triterpenoids like glycyrrhizin and its aglycone glycyrrhizic acid, polyphenols, and immunomodulating heteropolysaccharides.102,103 Licorice extract inhibited the growth and cytopathology of herpes, as well as inactivating herpes simplex virus particles irreversibly. In vivo, glycyrrhizin (GR), administered intraperitoneally could increase the survival rate of mice by 2.5 times (37.5%–39.0% to 81.8%–83.3%) that were infected by HSV-1 with herpetic encephalitis. GR also reduced HSV-1 replication in vivo.104 Glycyrrhizic acid inhibits the growth of several DNA and RNA viruses in cell cultures and inactivates Herpes simplex 1 virus irreversibly.101 A recent study shows that treatment of cells latently infected with Kaposi’s sarcoma–associated herpes virus (KSHV), a member of the herpes family, with glycyrrhizic acid, a component of licorice, reduces synthesis of a viral latency protein and induces apoptosis of infected cells, suggesting a novel way to interrupt latency.105

Reishi

Considered an adaptogenic and immunomodulating herb, a number of studies have demonstrated activity of Reishi against HSV. One study, looking at the mechanisms of action of Reishi against HSV-1 and -2 found that the Ganoderma lucidum proteoglycan (GLPG), obtained by liquid fermentation of the mycelia, works by inhibiting viral replication by interfering with the early events of viral adsorption and entry into target cells.106 Two protein-bound polysaccharides, a neutral protein-bound polysaccharide (NPBP) and an acidic protein-bound polysaccharide (APBP), isolated from water soluble substances of Reishi were also found to be effective against HSV-1 and -2. APBP was found to have a direct virucidal effect on HSV-1 and -2. APBP did not induce interferon (IFN) or IFN-like materials in vitro and is not expected to induce a change from a normal state to an antiviral state. APBP in concentrations of 100 and 90 µg/mL inhibited up to 50% of the attachment of HSV-1 and -2 to cells and was also found to prevent penetration of both types of HSV into cells. These results show that the antiherpetic activity of APBP seems to be related to its binding with HSV-specific glycoproteins responsible for attachment and penetration, and APBP impedes the complex interactions of viruses with cell plasma membranes.107 Virucidal effects of Reishi extracts have also been identified by other researchers.108,109 A study by Oh et al. demonstrated potent synergistic antiviral effects against HSV-1 and -2 showed when combining APBP and acyclovir, suggesting the development of APBP as a new antiherpetic agent.110 Reishi has also demonstrated beneficial effects in the treatment of herpes zoster, reducing postherpetic neuralgia.111 Reishi is usually taken as a decoction or tablet. Although tinctures are also available, the polysaccharides are likely more bioavailable in whole or water-extracted forms.

Sage and Rhubarb Combination

Essential oil (EO) rich herbs, for example, thyme (Thymus vulgaris), tea tree, and lemon balm, and anthraquinone-rich herbs such as aloe and St. John’s wort all contain antimicrobial activity, some specifically against HSV. A combination ointment containing sage (Fig. 8-7) and rhubarb extracts, the former EO rich and the latter anthraquinone-rich, and a product containing sage alone, were evaluated for their efficacy against HSV. A total of 149 patients participated: 145 (111 female, 34 male) of whom 64 received the rhubarb-sage cream, 40 the sage cream, and 41 Zovirax cream. They could be evaluated by intention-to-treat analysis. The dried rhubarb extract used was a standardized aqueous-ethanolic extract according to the German Pharmacopoeia and the dried sage extract an aqueous extract. The reference product was Zovirax cream with the active ingredient acyclovir. The mean time to healing in all cured patients was 7.6 days with the sage cream, 6.7 days with the rhubarb-sage cream, and 6.5 days with Zovirax cream. There were statistically significant differences in the course of the symptoms. For the parameter swelling, at the first follow-up visit there was a significant advantage for Zovirax cream compared with sage cream, and for the parameter pain, at the second follow-up visit there was a significant difference in favor of the rhubarb-sage cream compared to the sage cream. The combined topical sage-rhubarb preparation proved to be as effective as topical acyclovir cream and tended to be more active than the sage cream.89

St. John’s Wort

Hypericin and related compounds have been shown to have selective activity against viruses, both in vitro and in vivo, including HSV-1 and -2.112,113 A prospective double-blind placebo-controlled study of St. John’s wort extract compared with placebo was conducted on 110 patients with herpes genitalis. Patients were given a 90-day treatment protocol of 300 mg tid, and 600 mg tid on the days of herpes outbreaks. Symptoms were significantly and equally reduced compared with placebo, including severity of episodes, size of affected area, and numbers of vesicles.20 Similar trials conducted by Koytchev et al. and Mannel et al. have yielded similar positive results.20,114 Herbalists include St. John’s wort in protocol for both internal and topical use for its positive effects on the nervous system, antiviral activity, and topically in tincture or salve, for its mild vulnerary and anti-inflammatory actions.

Tea Tree