chapter 46 Urology

HISTORY AND EXAMINATION

ADULT MALE

History

Current medications and allergies should be noted, as well as past surgical procedures.

Family history of prostate cancer will be potentially relevant to diagnosis and screening.

ADULT FEMALE

History

History will begin with the presenting complaint. Ask about frequency and urgency of micturition, nocturia and urinary incontinence, haematuria, loin pain and vaginal discharge. Ask about a history of past urinary tract infections, gynaecological conditions and procedures, menstruation pattern and bowel function. If appropriate, enquire about recent sexual activity.

UROLITHIASIS

AETIOLOGY

Theories of stone formation are by no means complete, partly due to the difficulties of mimicking in vivo disease with an in vitro model. What is clear, however, is that supersaturated urine is a prerequisite to stone formation. The nucleation theory suggests that stones originate from crystals in supersaturated urine, whereas the crystal inhibition theory suggests that it is an absence of urinary inhibitors that differentiates the stone former from the non-stone former. Some work has gone into examination of potential inhibitors, particularly magnesium and citrate. Types of stones are listed in Table 46.1.

| Type of stone | Incidence (%) |

|---|---|

| Calcium oxalate/calcium phosphate | 80–85 |

| Urate | 5–10 |

| Struvite (magnesium, ammonium, phosphate) | 5–10 |

| Cystine | ≈1–2 |

| Xanthine | ≈1–2 |

Risk factors for stone disease

THERAPEUTICS

PREVENTION

Where possible, avoid medications likely to increase stone risk.

Diet

URINARY TRACT INFECTION

INVESTIGATIONS

THERAPEUTICS

PREVENTION

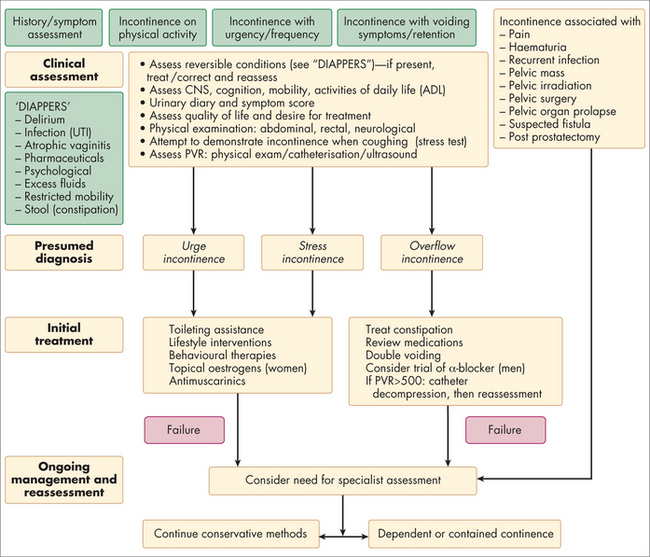

INCONTINENCE

Urinary incontinence may be classified as:

AETIOLOGY

(See Fig 46.1) Stress incontinence is more commonly seen with multiple vaginal deliveries and increasing age. Female continence is dependent on the supports of the bladder neck and urethra as well as the external sphincter located at the mid-urethral level. Tissue laxity and atrophy allow hypermobility with incomplete urethral closure. Male SUI is much less common and is usually due to traumatic sphincteric injury (e.g. prostatectomy for benign or malignant disease or pelvic fracture with urethral rupture).

THERAPEUTICS

Stress incontinence

Conservative treatment involves fluid management, timed voiding and pelvic floor muscle exercises. Smoking cessation, elimination of constipation, oestrogen replacement and correction of obesity are also appropriate. Surgical therapy for female SUI involves bolstering the mid-urethral complex or bladder neck suspension. Colposuspension surgery involves elevation of the tissues surrounding the bladder neck behind the pubis, thus preventing mobility. Colposuspension has been largely replaced by urethral sling procedures. Autologous or synthetic slings are placed via the obturator foramen or retropubic space around the middle or proximal urethra to form a hammock for urethral support. The outcome data for synthetic slings (trans-vaginal tape, transobturator tape, etc) are now quite mature and they seem to remain effective at long-term follow-up.

Complicated cases

Complicated cases may require more invasive therapy. Severe sphincteric deficiency such as that seen post prostatectomy or with lower motor neuron disease may be treated with an artificial urinary sphincter. An artificial sphincter involves the placement of a silicone cuff around the urethra, which is connected to a reservoir buried in the retropubic space. Fluid is cycled in and out of the cuff by a pump that is placed in the scrotum or labia. Debilitating UUI may require bladder augmentation surgery or a urinary diversion such as with an ileal conduit.

BENIGN PROSTATIC HYPERPLASIA

INVESTIGATIONS

INTEGRATED THERAPEUTICS

PROSTATITIS

Bacterial prostatitis is usually divided into acute and chronic, depending on the duration of symptoms. The National Institutes of Health classification is frequently used and is outlined in Box 46.1.

BOX 46.1 NIH classification of prostatitis

INVESTIGATIONS

The investigations for chronic prostatitis should include:

URINARY RETENTION

THERAPEUTICS

Simple measures can be tried, to assist voiding. Sitting in a warm bath, pain relief or simply sitting out of bed for the hospitalised patient can be useful manoeuvres. If catheterisation is required, the patient should be catheterised as described above. Some units prefer suprapubic catheterisation as a routine. The ability to carry out a trial of voiding without removing the catheter must be weighed against the additional morbidity associated with suprapubic catheterisation. There is good evidence that the addition of an alpha-blocker (e.g. tamsulosin 400 mcg OD) can improve the percentage of men who void following removal of the catheter. This is normally started on admission and requires at least two doses. Approximately half of men will void following a first episode of retention. In patients who have an obvious precipitant and minimal LUTS prior, this is more likely to succeed. In men who have had worsening symptoms over a long period culminating in an episode of retention, it is less likely and they are best managed with prostate surgery in the first instance.

RENAL DISEASE

Kidney disease is mentioned in a number of other chapters in the context of its association with other illnesses and risk factors. For example, it is discussed in the chapter on diabetes (Ch 26) in the context of complications and monitoring, and in the chapter on cardiovascular disease (Ch 25) due to its role in hypertension. This section of the chapter will therefore focus on kidney failure.

KIDNEY FAILURE

Acute kidney failure

Aetiology

AKF can arise from a variety of causes, including:

Chronic kidney failure

The majority of patients will be managed in general practice.

Aetiology

CKF can arise from diseases that primarily originate in the kidney itself, or from other illnesses that affect the kidney (Box 46.2). Many of these illnesses, such as type 2 diabetes, hypertension and vascular disease, are lifestyle related and are therefore preventable.

Signs and symptoms

The symptoms associated with CKF are largely due to effects on fluids and electrolytes, homeostasis and erythropoietin. Symptoms (e.g. pruritis), signs (e.g. unexplained hypertension, fatigue or anaemia) and laboratory findings (e.g. proteinuria, uraemia) should raise the clinical suspicion of CKF. Box 46.3 outlines the main symptoms and signs of CKF.

Investigations

TABLE 46.2 International Diabetes Federation guidelines8 on albuminuria

| Urinary ACR (mg/mmol) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Women | Men | |

| Normoalbuminuria | < 3.5 | < 2.5 |

| Microalbuminuria | 3.5–35 | 2.5–25 |

| Macroalbuminuria | > 35 | > 25 |

The eGFR varies with age, gender and size, and so what would be considered normal kidney function needs to be interpreted in light of these parameters.

CKF is divided into five stages according to the eGFR:

Patients with moderate levels of kidney failure or above should be referred to a renal specialist (Box 46.4) for advice and co-management.

Integrative management

BLADDER CANCER

INVESTIGATIONS

Endoscopic examination of the lower urinary tract (cystoscopy) is the diagnostic standard for bladder cancer, and is combined with urinary studies and radiological imaging. Urinary cytology has only moderate sensitivity but good specificity for the detection of urothelial cancers, and is more useful in post-therapy surveillance.

RENAL CELL CANCER

THERAPEUTICS

Radical nephrectomy is the standard treatment for RCC. Partial nephrectomy is an option for smaller (< 4 cm) exophytic tumours and may be mandatory where radical nephrectomy will result in renal insufficiency, such as in a solitary kidney. Cancer-specific survival rates for partial nephrectomy are equivalent to radical nephrectomy for treating small renal tumours. Both radical and partial nephrectomy can be accomplished open or laparoscopically. Unfortunately, up to a third of patients present with metastatic disease.

ADRENAL DISEASES

Paired adrenal glands lie adjacent to the upper aspect of each kidney. These glands are composed of an outer cortex (mesodermal origin) and inner medulla (neuroectodermal origin). Adrenal cortical function involves the production of aldosterone, cortisol and adrenal androgens as part of normal homeostasis. The adrenal medulla is composed of chromaffin cells, which produce the catecholamines epinephrine and norepinephrine.

The adrenal gland may be the site of a variety of benign and malignant diseases (Table 46.3).

| Non-neoplastic | Neoplastic |

|---|---|

| Adrenal cyst | Adrenal adenoma |

| Adrenocortical hyperplasia | Adrenal carcinoma |

| Haematoma/abscess | Phaeochromocytoma |

| Myelolipoma | Metastatic deposit |

PENILE DISORDERS

Penile disorders may be classified anatomically and functionally as:

DISORDERS OF THE PREPUCE

Phimosis is stenosis of the preputial orifice that prevents retraction of the foreskin over the glans. This may be considered primary (childhood) or secondary (previously retractible). Congenital adhesions between the glans and prepuce are present at birth and tend to loosen with age; about 90% of boys have a retractible foreskin by the age of 3 years. Inability to retract the foreskin persists in 1% of pubertal males. Pathological phimosis occurs from trauma or infection, with a resultant fibrotic ring. Recurrent infections of the glans and preputial sac (balanoposthitis) may cause and result from phimosis. Infections may result from poor foreskin hygiene (failure to retract the foreskin and clean underlying smegma daily) and are more common in diabetics.

DISORDERS AFFECTING THE GLANS

Penile carcinoma is an uncommon condition that is largely preventable with adequate penile hygiene.

SEXUAL AND FUNCTIONAL DISORDERS

Many drugs (alcohol, opiates, hypotensives, phenothiazines and sedatives) are thought to be contributory, although the association is often poorly understood. Functional causes associated with psychogenic factors are not as common as a primary cause; these are usually diagnoses of exclusion once organic causes have been excluded.

emedicine, urology articles (an online resource for patients and doctors). http://emedicine.medscape.com/urology.

European Association of Urology, urological guidelines (authoritative and much used). http://www.uroweb.org/guidelines/online-guidelines/.

Kidney Health Australia, Chronic kidney disease management in general practice. http://www.kidney.org.au/LinkClick.aspx?fileticket=dSUlcQgPd6o%3d&tabid=635&mid=1584.

Society for Chronic Pelvic Pain and Interstitial Cystitis. http://ucpps.org/.

1 Goldfarb DS, Coe FL. Prevention of recurrent nephrolithiasis. American Family Physician 2009; 15 November. Online. Available: http://www.aafp.org/afp/991115ap/2269.html.

2 Sea J, Poon KS, McVary KT. Review of exercise and the risk of benign prostatic hyperplasia. Phys Sportsmed. 2009;37(4):75-83.

3 Wilt TJ, MacDonald R, Ishani A. Beta-sitosterol for the treatment of benign prostatic hyperplasia: a systematic review. BJU Int. 1999;83(9):976-983.

4 Kaplan SA, Volpe MA, Te AE. A prospective, 1-year trial using saw palmetto versus finasteride in the treatment of category III prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome. J Urol. 2004;171:284-288.

5 Wilt T, Ishani A, MacDonald R, et al. Pygeum africanum for benign prostatic hyperplasia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2002;1:CD001044.

6 Konrad L, Müller HH, Lenz C, et al. Antiproliferative effect on human prostate cancer cells by a stinging nettle root (Urtica dioica) extract. Planta Med. 2000;66(1):44-47.

7 Shoskes DA, Kannan Manickam AE. Herbal and complementary medicine in chronic prostatitis. World J Urol. 2003;21:109-113.

8 Elist J. Effects of pollen extract preparation Prostat/Poltit on lower urinary tract symptoms in patients with chronic nonbacterial prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Urology. 2006;67:60-63.

9 International Diabetes Federation. Clinical Guidelines Task Force. Global guideline for type 2 diabetes. Brussels: IDF, 2005.