Chapter 9 Urogenital problems

9.1 Introduction: urinary tract

History

Urinary disease presents with a relatively small number of defined symptoms as presenting problems. Patients may present with lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS) that are subcategorised as storage or irritative symptoms (urinary frequency, urgency, nocturia, dysuria), voiding or obstructive symptoms (change in strength of the urinary stream) and incontinence. Ongoing obstructive LUTS may eventually present as retention of urine. Haematuria may be due to benign or malignant disease; renal pain (colic) results from obstruction, most often with ureteric calculi. Occasionally there may be recognition of a renal mass. However, the majority of renal masses are now detected as incidental findings on abdominal imaging performed for investigation of often unrelated symptoms. Prostate cancer is increasingly detected in the context of overall health assessments or as a case finding during assessment of LUTS. A careful assessment of the history often suggests the diagnosis, which is usually supported by an imaging modality.

Patients should be assessed for evidence of renal failure (Ch 10.7). Symptoms of chronic renal failure include nocturnal polyuria and a constellation of nonspecific symptoms: anorexia, nausea and vomiting, headache, visual disturbances, lethargy, sallow skin, oedema and general malaise.

Physical examination

A renal swelling has the following characteristics:

Diagnostic tests

9.2 Loin pain

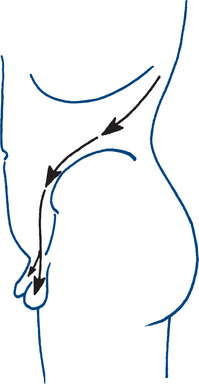

The most common cause of loin pain is acute or chronic renal pain. Acute obstruction with dilatation of the urinary tract above the bladder causes acute renal pain (renal or ureteric ‘colic’) that has a wide distribution. Pain often radiates from the flank on the affected side to the anterior abdomen and groin and may extend into the penis or scrotum, or labia in females, or into the upper thigh (Fig 9.3). It is severe and prostrating in character and although described as ‘colic’ is usually continuously and unremittingly severe until relieved. Renal ‘colic’ is due to ureteric obstruction by stone, crystal, blood clot, necrotic papilla or infective debris, or back pressure due to a neuropathic bladder. Chronic renal pain gives a dull loin ache and can be due to a variety of renal and perirenal causes.

Clinical assessment

4 Less common causes

Renal ‘colic’, without objective evidence of obstruction and requiring repeated narcotic injections without relief, should raise suspicion of narcotic addiction but this should always be a diagnosis of exclusion. Such patients may discolour their urine with blood obtained from finger-prick to make the clinical picture more convincing. Occasionally herpes zoster (shingles) may present with loin pain.

Diagnostic plan

On presentation to hospital, the diagnosis is usually made after clinical history, examination and then urine dipstick with a commercial kit with positive for red blood cells is demonstrated and infection largely excluded by the absence of nitrites. The imaging modality to confirm the diagnosis will then usually be a non-contrast spiral computed tomography (CT) scan of the abdomen and pelvis. An accompanying plain abdominal X-ray is helpful in planning treatment and elucidating if the stone is radio-opaque or radiolucent. The X-ray may demonstrate an opaque calculus (85% of urinary calculi are radio-opaque — Box 9.1), which needs to be distinguished from phleboliths and other opacities. The CT findings consistent with an obstructing stone include perinephric fat stranding, dilatation of the renal pelvis and/or ureter and identification of the stone itself. The presence of the contralateral kidney should be sought and the size and position of other calculi that appear bright white should be noted. Urine should then be sent for formal microscopy and culture to definitively exclude infection and quantitate the haematuria, and to look for crystals (oxalate). At the time of presentation, blood should be drawn for full examination, creatinine, urea and electrolytes to ascertain renal function and screen for metabolic abnormalities and serum uric acid; calcium and phosphate estimations are also useful screening tests for major metabolic abnormalities. Stone analysis is done if the stone is recovered. The patient is instructed to strain the urine to check for stone passage and obtain the stone for analysis.

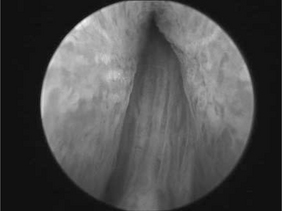

Prior to the popularity of CT for diagnosis, which has the advantages of high sensitivity, speed, lack of contrast administration and ability to detect other intra-abdominal pathologies, intravenous urography (IVP) was used to confirm the diagnosis of urinary obstruction, with demonstration of the causative calculus, either as a radio-opaque shadow in line with the ureter or as a radiolucent filling defect (Figs 9.4a–c), or showing a dilated upper urinary tract as the aftermath of a stone that has passed. IVP is now rarely performed in most emergency departments but is a useful adjunct if the diagnosis is equivocal. Ultrasound can be helpful in excluding other intra-abdominal and pelvic lesions or to demonstrate and serially monitor upper urinary tract dilatation due to obstruction. Ultrasound is thus of particular value in children, in whom repeated X-rays should be avoided. Renal colic with symptoms and signs of pyelonephritis (fever, systemic toxicity) always requires urgent imaging. An obstructed and infected kidney requires urgent relief, whereas obstruction in the absence of infection can be observed over the course of a week or more without likelihood of renal parenchymal damage.

Treatment plan

Renal colic

Parenteral narcotic injection is required for pain relief. Intravenous pethidine or morphine relieves pain within a short time and a protocol of administration is usually followed in the emergency department. In most instances the pain settles after adequate administration of initial narcotic and a period of observation in the emergency or short-stay ward. Adequate antiemetic should be given with the narcotic. Oral nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDS) should be given with the initial narcotic (e.g. indomethcin 100 mg) and these can be given as suppositories if the patient is not tolerating oral medication. Precautions should be taken in those with a history of peptic ulcer disease. NSAIDS are a very effective form of pain relief in renal colic and can be continued as an outpatient. The patient can also be given oral narcotics such as paracetomol.

Management of urinary calculi

Indications for stone removal (Box 9.2). Removal is indicated only when parenchymal damage is a concern, for example, with unresolved urinary infection or the stone seems very unlikely to pass spontaneously, as with large calculi (>1 cm diameter) or persisting pain without progress. It is also mandatory in the case of a solitary kidney, where anuria may ensue.

Methods of stone removal. Stone removal is largely an endoscopic procedure via the upper or lower urinary tract depending on the site of the stone, with or without the use of an energy source to shatter the stone prior to removal (Fig 9.4d). The other key method of removal is extracorporeal shock wave lithotripsy (ESWL, Fig 9.4e). Rarely is open stone removal required (open ureterolithotomy, pyelolithotomy or anatrophic nephrolithotomy). Laparoscopic surgery may now be used for difficult, large, impacted ureteric stones that cannot be manipulated up or down. The following methods are most frequently used in the operative management of urinary tract calculi.

Management of recurrent urinary calculi

Recurrent calculi are prevented by the general measures of maintaining dilute urine of high volume, including fluids at night, and by eliminating obstructions, infections and immobilisation. More specific measures include treatment of hypercalciuria by low-calcium diet and diuretics, of hyperparathyroidism by parathyroidectomy, of renal tubular acidosis by correction of acidosis and by making the alkaline with oral sodium and potassium bicarbonate treatment and of hyperuricosuria by allopurinol, restricting protein and alcohol intake and alkalinising the urine. General measures for those with no specific metabolic abnormality include maintaining a high fluid intake, avoidance of a high intake of animal protein and salt and oral preparations that are usually citrate-based to act as an inhibitor of stone formation.

9.3 Painless haematuria

Clinical assessment and urine microscopy

Normal urine shows fewer than four erythrocytes per high power field in microscopy of fresh centrifuged specimens. Microscopy of a fresh specimen can distinguish between glomerular and urothelial erythrocytes. The former are irregular in outline and haemoglobin content (dysmorphic). The latter are usually undamaged circular cells with normal haemoglobin content or ghost cells of normal shape lacking haemoglobin. Dysmorphic cells are most easily recognised under phase-contrast microscopy. The presence of red cell casts or heavy proteinuria is also indicative of glomerular disease.

Diagnostic and treatment plan

Cases of haematuria require full investigation and the following are suggested.

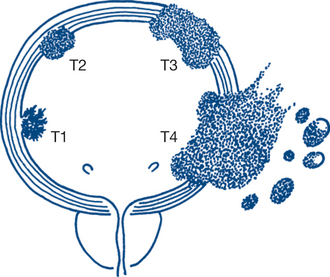

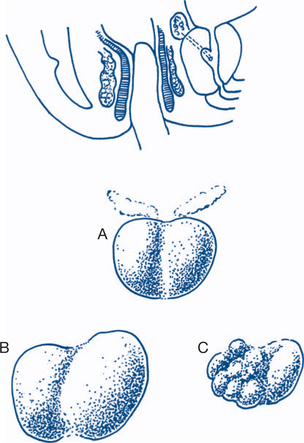

The bladder is the most frequent site but all urothelium is at risk. Tumour malignancy and prognosis exhibit a spectrum from fronded papillary tumours of low grade or medium malignancy that do not invade the lamina propria, to those that are sessile, ulcerated and invasive from the onset. These latter tumours spread by direct invasion, via lymphatics and at a later stage by the bloodstream. Simple staging into superficial disease and muscle-invasive disease is helpful in determining treatment and prognosis (Figs 9.6a and b).

More precise staging is from Ta/T1 to T4, namely:

Deeper tumours extending into the detrusor muscle need surgical resection with radical cystectomy and diversion of ureters to an ileal conduit or in some circumstances to a neobladder created from a bowel segment. Radiotherapy and endoscopic removal may be used as primary therapy in muscle-invasive disease with or without chemotherapy but is more often reserved for those unfit for radical surgery.

The usual treatment is radical nephrectomy if the tumour is locally confined. Small RCCs are often now managed with laparoscopic radical nephrectomy. Where there is a requirement for nephron-sparing surgery, for example, in a single kidney, a partial nephrectomy can be performed. Cancer-specific survival figures for the management of small RCCs of less than or equal to 4 cm with partial nephrectomy are now equivalent to those for radical nephrectomy, making partial removal an alternative. Occasionally, radical nephrectomy can be combined with removal of a locally resectable single-lung metastasis.

9.4 Lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS)

Clinical features and diagnostic plan

Urinary tract infections

Sterile pyuria may also be detected and if it is obstructing, lesions such as papillary necrosis and specific infections such as tuberculosis or schistosomiasis should be excluded. Tuberculosis should also always be considered as a possible cause in the case of infection that does not respond to adequate antibiotic treatment.

Storage LUTS

Symptoms such as frequency, urgency and urge incontinence are common in the ageing patient, especially females, and relate to altered ability to store urine or in the minority, an overproduction of urine. The most common cause of urinary symptoms in elderly males is bladder neck obstruction. Painful frequency is often associated with difficulties with the urinary stream (Ch 9.5). Where infection has been excluded and there is no other suggestion of pathology, such as haematuria, renal injury, drug-induced diuresis, prior pelvic radiotherapy or neurological condition, the diagnosis is usually an overactive bladder (OAB) secondary to idiopathic detrusor overactivity. This is managed initially with bladder drill and assessment of intake and output, optimally in a multidisciplinary environment with the assistance of continence nurse advisors and physiotherapists. Anticholinergic drugs are also used with caution in the elderly; these act by antimuscarinic means and are associated with side effects of dry mouth, reflux oesophagitis, constipation and dry eyes (e.g. propantheline, oxybutnin). Newer selective agents show promise in their improved side effect profile (e.g. tolterodine, solfenacin). More complex surgical treatment is similar to that for the management of urge-related incontinence.

Voiding LUTS

LUTS commonly present in the older male who complains about slowing of urinary stream, hesitancy at starting the stream, intermittency of stream and post-micturition dribble. The ultimate complication of these symptoms is presentation with acute urinary retention. These cases are considered to be voiding LUTS (obstructive) and may coexist with storage (irritative) symptoms, as defined in the previous section. Storage symptoms develop in concert with obstruction as the bladder decompensates due to the ongoing pressure required to expel urine. Females may also experience voiding-related LUTS and atrophic vaginitis can be a potent but curable cause of urethral stenosis. The concept of poor urinary stream and obstruction is discussed in detail in the next section.

9.5 Poor urinary stream

Symptoms and signs

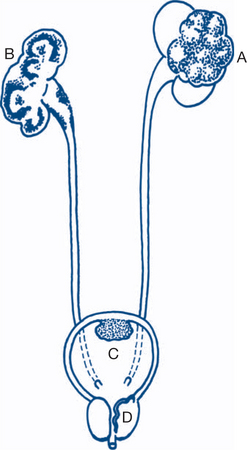

In patients with decreased urinary stream the stream is slow to start (hesitancy), lacks power and pressure, may stop and start (intermittency) and dribbles terminally. This may progress to acute or chronic retention of urine. The storage symptom of painless frequency is a common associated symptom. This is often more troublesome at night, is of small volume and often associated with urgency. Urge incontinence or in longstanding obstruction, overflow incontinence, may occur. Symptoms of the complications of obstruction may also be present (Fig 9.7a). These include: urinary tract infection with frequency, dysuria and haematuria; bladder diverticula predisposing to cystitis and stone formation; prostatitis and epididymo-orchitis; vesical calculus causing haematuria, dysuria and frequency; and, eventually, renal injury.

On examination the signs of upper urinary tract distension, and of renal injury, are sought.

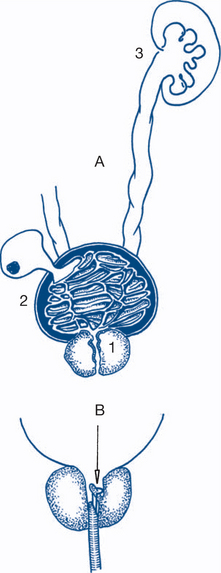

Benign prostatic obstruction

On DRE, the prostate is enlarged, smooth, regular, mobile and soft. Benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH) is normally present in most males aged over 60 years. A variant is a small muscular prostate, which gives similar symptoms of bladder neck obstruction but the prostate feels of normal size and consistency. Hence the size of the prostate on rectal examination will not always correlate with the degree of symptoms reported (Fig 9.7b).

Diagnostic plan

Prostate-specific antigen (PSA). PSA is a serine protease produced by prostate cells and involved in the liquefaction of semen. It is a prostate-specific test that is elevated in conditions that affect the prostate, such as infection, hypertrophy, infarction and malignancy. As a result it is an imperfect test as a screening tool for prostate malignancy. The current recommendations by the Urological Society of Australia and New Zealand as to who should receive a PSA test reads ‘PSA based testing, and subsequent treatment where appropriate, has been shown to reduce prostate cancer mortality in large randomised studies and therefore should be offered to men after informing them of the risks and benefits of such testing. Valuable predictive information can be obtained through even a single PSA test and prognostic information can be obtained by biopsy where indicated. Where possible, over-treatment should be avoided and surveillance with early intervention discussed with carefully selected patients’.[1] Hence the test can be offered to fit men with a good life expectancy, with or without LUTS if they are adequately informed prior to the test of its limitations and the likely ramifications of the test returning positive. As this is an area of controversy the reader is urged to refer to the latest literature on the topic and the guidelines produced and updated by their local professional bodies. The upper-most value of the PSA test as normal is also a point of contention but for most purposes, normal is less than 4 ng/ml. However, in a younger male with a small prostate, lower values may be considered abnormal. If concern exists, the patient should be referred to a urologist.

CT scanning of the pelvis and abdomen helps stage malignant disease in some cases.

Treatment plan

1 Prostatic obstruction

Conservative treatment is appropriate for many men with poor urinary stream due to BPH. Some men will require no intervention and a policy of observation may be adopted. Alternative medicines such as saw palmetto, for which there is some published data to support its use, might be used. For men with more bothersome symptoms wishing to avoid surgery, alpha-blockers such as prazosin or the more selective, tamsulosin, may be prescribed. 5HT reductase inhibitors such as finasteride lead to gland shrinkage by blocking the peripheral conversion of testosterone to dihydrotestosterone and can be used in conjunction with an alpha-blocker. They are not widely used in Australia due to side effect profile and cost. For men who are poor operative candidates, intra-prostatic stents can also be used but these carry the risk of encrustation and migration.

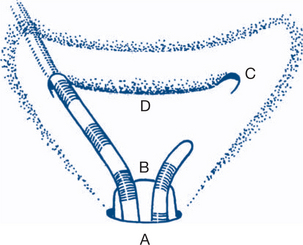

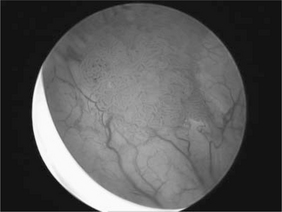

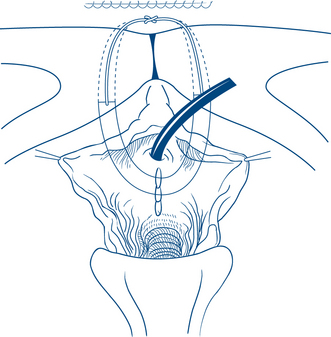

The operative procedure is now almost invariably transurethral resection of the prostate (TURP) using a resectoscope (endoscopic). The method is suitable for BPH, fibrous prostates or malignant prostates causing obstruction (Fig 9.8a and b).

All radical treatments for prostate cancer carry varying risks to future potency, continence and surrounding structures; for example, rectal toxicity associated with radiotherapy. For this reason, extensive pre-treatment counseling takes place to discuss the various risks and benefits of each approach.

9.6 Urinary retention

Clinical assessment

Retention may be acute or chronic. Acute retention is associated with a painfully distended bladder that can be palpated above the pubis on physical examination as a tense, dull, pear-shaped midline swelling arising out of the pelvis. Suprapubic compression causes an urge to urinate with lesser degrees of distension. By far the most common cause of acute retention in the elderly male is benign or malignant prostatic obstruction; occasionally a lower tract stricture is responsible. It is notable that the obstruction caused by benign prostatic enlargement is dynamic; the prostate can be easily traversed by a large instrument or catheter, it is just that the pressure flow dynamics between the bladder and outlet have progressed to the point where no urine will pass. Drugs often contribute to precipitating an episode of acute retention, particularly in elderly males. Alcohol, anticholinergic agents, sympathomimetic agents, beta-blockers and tricyclic antidepressants are the most common. Acute retention may also be due to neurologic disorders such as multiple sclerosis or spinal injury or may be of psychogenic origin. In women, apart from neurogenic and psychogenic causes, the gravid uterus or fibroids or an ovarian cyst may cause retention by pressing on and obstructing the bladder. Postoperative retention is usually acute and follows operations on the abdomen, pelvis, perineum, anorectum, genitalia and inguinal region and is due to pain inhibiting relaxation of the external sphincter and contraction of abdominal muscles.

Treatment plan

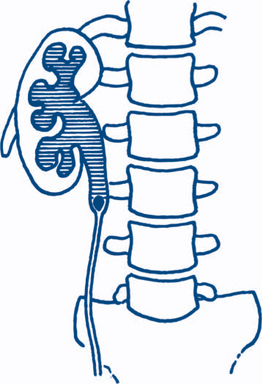

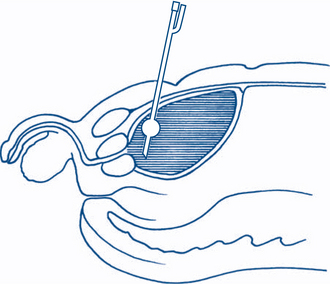

For patients with acute retention requiring continuing drainage, a balloon catheter, preferably made of silicone rubber, is desirable. The catheter should not be so large as to hinder free drainage of urethral secretions and a 12F Foley catheter is satisfactory in an adult in most cases. If a Foley catheter cannot be passed, a thinner (6–8F) plastic Gibbon catheter may succeed in navigating a stricture, but often if stricture is present direct visualisation will be needed or suprapubic drainage. In the instance of a large prostate, it is often easier to pass a larger size 16 or 18F catheter with a little more inherent rigidity than a smaller catheter. It will more easily pass through the curve of the bulbar urethra without coiling up than might a smaller bore catheter. If urethral catheterisation for urinary retention is unsuccessful, the distended bladder can be drained suprapubically by percutaneous insertion of a balloon suprapubic catheter. Again, an experienced operator is required and kits based on Seldinger techniques now exist to ensure safe suprapubic puncture without traversing other organs or vessels. Any patient who has had a prior laparotomy or has a lower midline abdominal incision should have a preplacement ultrasound to mark the site of safe puncture (Fig 9.9).

9.7 Urinary incontinence

Clinical features

These vary with the cause and may also commonly overlap.

1 Stress incontinence

Stress incontinence is very common in women. The normal competence of the female urethra depends on:

2 Urge incontinence

Patients with urge incontinence have frequency of micturition by day and night, cannot put off the desire to void and may be incontinent on the way to the toilet, often with large volume losses. Factors causing local irritation or stimulation of the detrusor muscle, such as urinary infections, stones, tumours, neurological lesions and the urethral syndrome, must be identified, but in many cases the cause is idiopathic detrusor overactivity. Detrusor overactivity (which is an urodynamic diagnosis) or OAB can lead to LUTS or incontinence (OAB wet). Other factors contributing to overactivity or low compliance of the bladder are a small capacity bladder, due to irradiation or chronic infection. Detrusor overactivity may also be caused by neurological disease and a history should be sought in all cases of urge incontinence. Careful neurological assessment to exclude neuropathies includes testing for perineal sensation, anal sphincter tone and for scrotal and anal reflexes.

Treatment plan

Treatment is then primarily aimed at correcting urethral hypermobility or intrinsic sphincter deficiency causing stress incontinence or the OAB. Overlap of the two conditions is common and characterisation of the cause can be helped in difficult instances by urodynamic studies, which are used to demonstrate objective abnormalities. Bladder pressures and flow rate recordings can be combined with radiographic imaging (video or fluoroscopic urodynamics). Parameters measured include flow rate, residual urine, bladder volume, compliance, and voiding pressures and imaging during voiding.

1 Stress incontinence

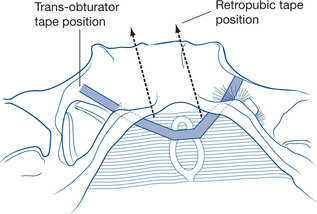

Over 100 operations have been described to correct stress incontinence. Most aim to buttress and support the tissues surrounding the bladder neck and to draw the urethra upwards behind the pubis. Abdominal or vaginal approaches can be used to achieve these aims. The most common procedures now rely on the passage of synthetic, autologous or biomaterial slings or tapes around the mid or proximal urethra and into either the retropubic space or via the obturator canal (Figs 9.10a and b). Retropubic (Burch) colposuspension is another option that can be performed either open or laparoscopically for the treatment of incontinence.

9.8 Penile lesions

The penis has urinary and sexual functions. Disorders can be grouped anatomically and functionally.

Clinical assessment and diagnostic tests

1 Disorders affecting the foreskin

Paraphimosis is inability to replace the prepuce over the glans after its retraction, due to a constricting ring behind the glans. Paraphimosis is a potential danger of forcible retraction of a phimosed prepuce. Paraphimosis is a specific danger after urethral catheterisation if the foreskin is left retracted after catheter insertion. Continuing paraphimosis leads to oedema and congestion of the glans, creating a vicious cycle. On examination the glans is swollen and oedematous. A deep groove is seen just proximal to the glans, created by the tight meatal skin. This constricting band may spontaneously split, ulcerate and weep.

3 Disorders affecting the glans

4 Disorders affecting the shaft

Sebaceous (epidermoid) cysts are most common in the scrotal skin but may occur on the penis.

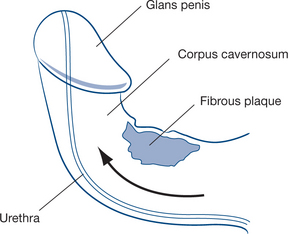

Subcutaneous induration of the shaft with a firm, nontender plaque of fibrous tissue in the fascia surrounding the corpus cavernosum on one or both sides is due to Peyronie’s disease, a condition of unknown cause akin to Dupuytren’s disease and which results in irreversible damage of the tunica albuginea of the corpora cavernosa. Peyronie’s disease is one of the causes of chordee during erection (Fig 9.11). The natural history of the disease is an active and painful phase of plaque development and then a quiescent phase. The active phase is treated symptomatically and no further treatment of the quiescent phase is required unless chordee that limits voiding in the upright position or sexual penetration results from the plaque.

5 Sexual and functional disorders

Priapism is a prolonged erection of greater than six hours and is a urological emergency. It can be considered as high flow (arterial) or low flow (venous) in cause. Low-flow priapism occurs where there is venous stasis that can be due to multiple causes, including persistent spasm of the venous smooth muscle sphincters that maintain erection, after use of intracavernosal injection for impotence, conditions causing hypercoaguable states such as sickle cell anaemia, multiple myeloma or leukaemia, other malignancy and other drugs including anticoagulants, phenothiazine, fluoxzetine and cocaine. High-flow priapism results from an arteriovenous anomaly after pelvic, perineal or penile trauma and unlike low-flow, is generally not painful early on. If prolonged, priapism of either cause will lead to thrombosis of the veins draining erectile tissue. Subsequently, even though priapism is relieved, there may be permanent impotence. The corpora cavernosa are stiff and distended and painful, the corpus spongiosum and glans are flaccid.

Treatment plan

The treatment of carcinoma is by amputation or local excision with a 2 cm margin. Inguinal gland management is usually delayed because of the frequency of infection within the nodes. In many cases the nodes disappear with control of infection. Later excision of inguinal nodes is essential if they are involved. The decision to explore and excise impalpable lymph nodes is based on the assessment of the overall risk of the disease as determined by the clinical stage, histological grade and the presence of vascular invasion on histology.