Chapter 7 Abdomen and gut problems

7.1 Introduction

History — analysis of abdominal pain

Abdominal pain is the most common presenting symptom of surgical diseases of the gastrointestinal tract. It is usually categorised by its site and mode of onset, for example, chronic epigastric pain or acute right iliac fossa pain. Analysis of abdominal pain lends itself very well to the principles of problem solving. The patient is encouraged to describe the pain in their own terms. Specific questions are interpolated to clarify and elaborate particular points and to detect the most significant symptoms. Abdominal pain is often accompanied by associated symptoms that establish a pattern and assist the clinician in making a diagnosis. Precise localisation of the pain is the most useful step in its characterisation. Although visceral pain is less precisely localised than somatic pain, in most cases the pain can be localised to an abdominal area or region: upper, lower, right, left, central or generalised. Of almost equal importance to site is the mode of onset of the pain — whether acute or chronic. For pain in each abdominal region, a limited and manageable list of common causes exists — some specific to the area and some not. With these causes in mind a careful history is taken and physical examination performed focusing on the identification of the most likely cause. A general systems review is always important in the analysis of abdominal pain, particularly in relation to the gynaecological and urinary systems. Disorders of other systems (such as diabetes) sometimes present solely with abdominal pain or in themselves need attention and may have a bearing upon prognosis.

Location and migration

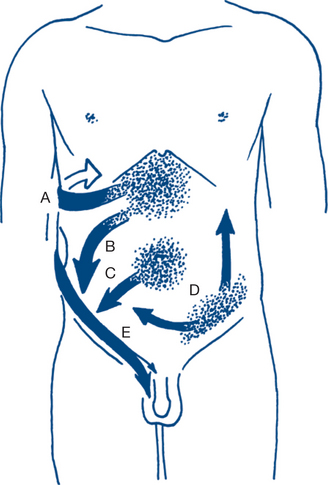

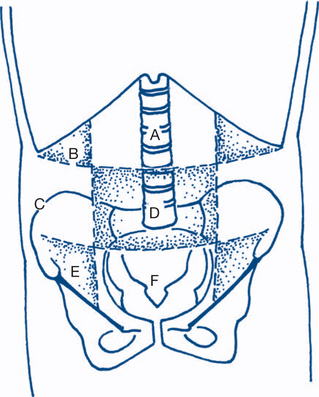

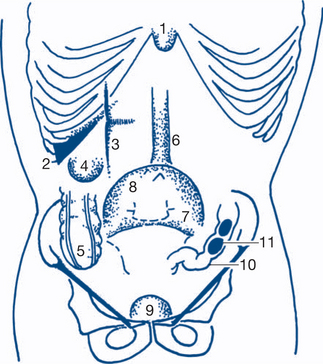

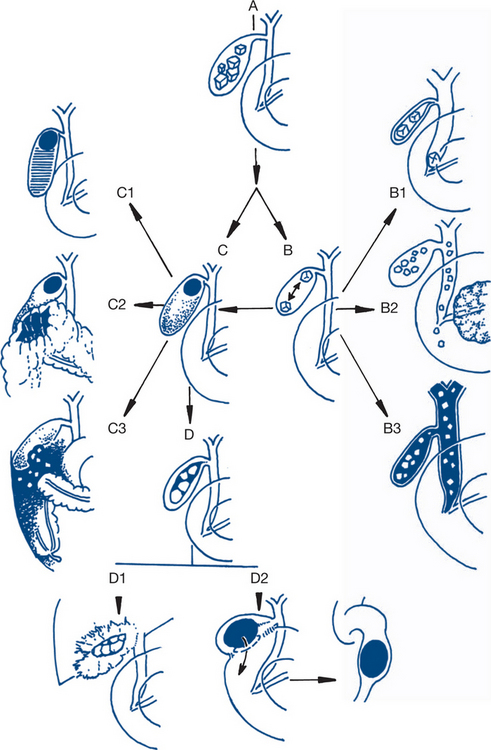

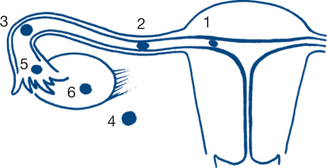

Whether abdominal pain is generalised or localised to an abdominal segment is the most important piece of information to obtain first. Migration of abdominal pain also often assists in diagnosis (Fig 7.1). Central or generalised abdominal pain is a common initial symptom of many diseases (appendicitis, bowel obstruction, visceral perforation). Persisting severe generalised abdominal pain suggests generalised peritonitis. Epigastric or right upper quadrant pain extending in a band around the abdomen suggests a biliary origin (‘colic’). Migration of central pain to the right iliac fossa over the course of several hours indicates appendicitis. This is an example of visceral pain evolving into a somatic pattern as local peritonitis develops with pathological progression of appendicitis. Another example of this phenomenon is migration of pain from the left iliac fossa to the whole abdomen may be associated with initial sigmoid diverticulitis with subsequent perforation and the development of generalised peritonitis.

Onset and duration

The time, pattern and character of onset and the duration of symptoms are elicited. Acute abdominal pain that persists for six or more hours suggests the presence of a surgical abdomen; so does a history of awakening at night with the pain, especially if pain precedes other symptoms such as vomiting or diarrhoea. A sudden and dramatic onset of pain suggests rupture of a previously intact structure (e.g. duodenum, colonic diverticulum, splenic capsule, aortic aneurysm). A gradual onset, progressively worsening over hours or days, correlates with inflammation. The onset after excessive alcohol intake suggests pancreatitis. A history of abdominal injury may be of importance. A latent period can exist between the time of trauma and presentation, as is seen with delayed rupture of the spleen. A latent period can also be seen in other acute abdominal conditions such as perforated peptic ulcer, intussusception, large bowel obstruction, gallstone ileus and intestinal infarction. Sometimes such a latent period gives the illusion of resolution of the problem and can delay or obscure diagnosis.

Associated symptoms

Nausea, vomiting and anorexia often precede pain of non-surgical origin: profuse vomiting as a main feature suggests upper small bowel obstruction; persistent anorexia following pain favours an organic cause; persistent vomiting from any cause can occasionally give haematemesis from a Mallory-Weiss tear in the lower oesophagus.

Physical examination

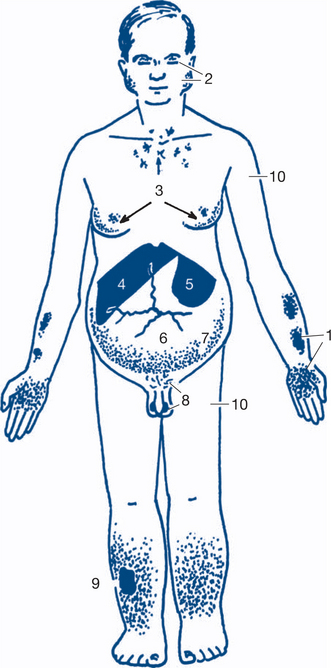

A general inspection of the patient should include a careful assessment of alertness, demeanour and hygiene. This is an ideal opportunity to identify features of chronic liver disease such as the presence of jaundice, pallor, bruising or purpura, pigmentation and loss of body hair (Fig 7.2). A record of the patient’s nutritional state should note whether body habitus is normal, obesity levels (or morbid obesity), whether there is loss of body mass and cachexia or evidence of fluid and electrolyte depletion. The preferred posture of the patient should be noted (e.g. sitting forward in acute pancreatitis, or supine and still in peritonitis.)

Examination of the periphery

The hands are examined. Nail changes include clubbing, which may be found in a number of gastrointestinal conditions, chronic liver disease, inflammatory bowel disease and malabsorption. Other changes such as leuconychia, indicating malnutrition and hypoproteinaemia, or koilonychia, suggesting iron deficiency, may be present. Palmar erythema, spider naevi and Dupuytren’s disease (palmar nodules, bands, contractures, pits and sinuses and knuckle pads) suggest alcoholic liver disease (Fig 7.2). Asterixis is a flapping tremor best seen with the hands in extension and is found in patients with portal systemic encephalopathy.

Abdominal examination

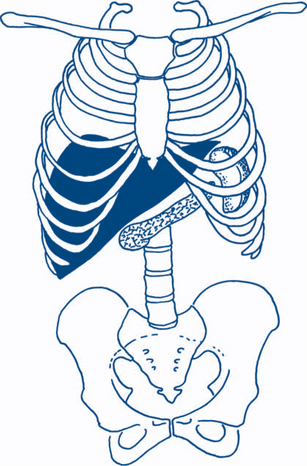

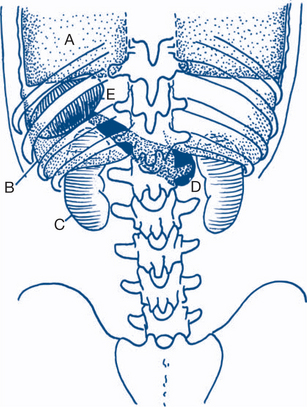

Figures 7.3 and 7.4 depict anterior and posterior surface markings of the abdominal viscera.

After inspection, the patient is asked if there is any tenderness and, if there is, its site. Palpation is started gently with the hand flat, at a site away from the site of maximal tenderness and then in all quadrants (Fig 7.5).

Then the abdomen is palpated more deeply using the flexor surface of the fingers — the use of two hands often helps to define masses (Fig 7.6).

The hernial orifices and genitalia are examined. It is important to distinguish normally palpable structures from abnormal masses (Fig 7.7).

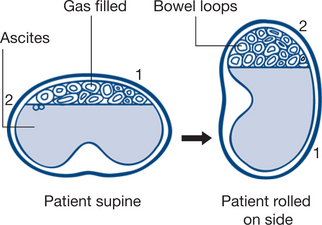

Routine examination for ascites is essential in the distended abdomen, by eliciting shifting dullness or a fluid thrill. Shifting dullness is shown to be present by rotating the patient about the long axis and demonstrating a change in the ‘Plimsoll line’ or transition line of dullness to percussion (Fig 7.8). Fluid thrill is detected by flicking the side of the abdomen and palpating for a transmitted impulse on the other side. Transmission of the impulse via the abdominal wall is blocked by another hand placed on the midabdomen.

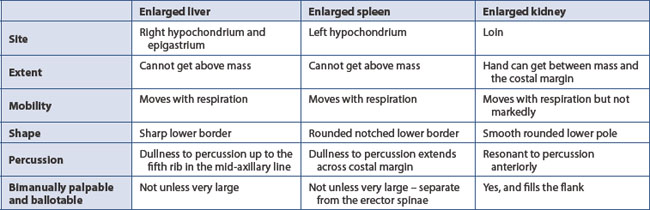

The following physical signs are sought: tenderness or resistance on palpation (voluntary or involuntary guarding); rigidity (extreme guarding); and rebound tenderness (best assessed by gentle percussion). A full description of any detected mass is often most usefully recorded as a simple schematic sketch in the medical record. The edge of a mass may be best delineated by deep palpation during inspiration (liver and spleen) or by percussion (Table 7.1). The site and depth of a mass are very important diagnostic features. Other important features include shape and consistency and whether the mass is mobile or fixed. Faecal masses are indentable.

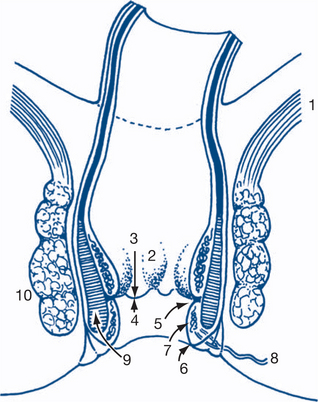

Anorectal examination

Initial inspection may reveal prolapsed haemorrhoids, perianal haematomas, external openings of fistulas and the dry or moist skin changes of pruritus. Examination of the anus during straining will be necessary to reveal prolapsing haemorrhoids or rectal prolapse. Anal fissures are normally not initially obvious on inspection, as they are located above the anal verge. Most fissures are seen in the midline posteriorly. Laterally placed fissures suggest an association with inflammatory bowel disease. Gentle retraction of the anal verge will usually expose the lower edge of a posterior fissure. Rectal examination (Fig 7.10) and proctoscopy may not be possible in such instances because of painful anal spasm. Palpation commences using the pulp of the index finger introduced slowly into the anorectum. The finger will usually reach 10 cm with a little pressure on the perineum or with the assistance of bimanual compression of the lower abdomen. As the finger is withdrawn the whole circumference of the rectum is examined. The indurated, elevated and ulcerated lesion of a carcinoma is characteristic. The capacity of the rectum should be noted. Masses outside the rectum in the pouch of Douglas may be palpable anteriorly. Anteriorly in the male the normal prostate is a firm rubbery bilobed structure about 3 cm in diameter. A shallow central sulcus may be palpated and the mucosa over the prostate should be freely mobile. In the male it is difficult to define anatomical structures above the base of the prostate. The prostate feels larger on examination if performed while the patient has a full bladder. In the female the cervix of the uterus or a vaginal tampon may be palpable anteriorly and should not be mistaken for a mobile extrarectal tumour. Faecal pellets in an intrapelvic sigmoid colon can simulate abnormal extrarectal lumps but faeces are regular and indentable. The glove should be examined for blood after completion of the digital examination.

7.2 ‘Acute abdomen’ (acute abdominal surgical emergency)

The timing of urgent surgery is also important; there must be adequate resuscitation but no undue delay before surgery. Early evaluation of the patient for signs of hypovolaemia and fluid depletion is therefore essential. The timing of surgery depends upon the response to resuscitation. As resuscitation begins, plans are made for any investigations required prior to surgery.

History and physical examination

A routine for physical examination in assessing the acute abdomen is as follows:

1. Acute appendicitis with perforation (see also acute right iliac fossa pain)

Perforation, with presentation as an acute abdomen, is seen most frequently in the young, the old and in patients with diabetes. In many series, perforation at the time of appendicectomy has occurred in almost half those patients under 10 years and over 50 years. It is unusual for the acutely inflamed appendix to perforate within the first 12 hours. Pain in appendicitis is often initially central and diffuse, followed by a shift to the right iliac fossa within a few hours. Pain is deep-seated, continuous and gradually increases in intensity. Nausea and vomiting are common, but vomiting is rarely pronounced or persistent and is rarely the first symptom. Diarrhoea is also rarely the first symptom (Table 7.2). Its presence suggests pelvic appendicitis. The development of perforation is accompanied by more severe generalised abdominal pain and higher fever.

Table 7.2 Comparison of clinical features of perforated pelvic appendicitis and gastroenteritis

| Perforated pelvic appendicitis | Gastroenteritis | |

|---|---|---|

| Progress | Steady deterioration | Usually nonprogressive |

| Pattern | Insidious onset of pain; later development of diarrhoea and tenesmus | Sudden onset of anorexia, nausea, vomiting and diarrhoea before pain |

| Associated upper respiratory tract infection (URTI) | No | URTI common with myalgia, photophobia and headache |

| Movement | Exacerbates pain | Writhing with spasms of pain |

| Abdominal signs | Often minimal early in the disease | Diffuse tenderness |

| PR examination | Tenderness and fullness in pouch of Douglas | Normal rectal examination |

| WCC | Leucocytosis | No leucocytosis |

2. Severe acute (haemorrhagic) pancreatitis

A small but important proportion of patients with severe acute pancreatitis present with an acute abdomen. The remaining patients with less severe disease present with localised acute upper abdominal pain (Ch 7.3). The most severe haemorrhagic form of the disease is associated with collapse and shock.

The onset of symptoms is occasionally explosive and can mimic a visceral perforation. Usually, however, increasingly severe pain develops over a period of several hours and spreads from the epigastrium throughout the whole abdomen and through to the back. Progressive dyspnoea and prostration (shock) are common. Persistent vomiting is often a feature of the illness (Table 7.3). Change of posture may aggravate or relieve the pain. Fever is variable.

Table 7.3 Comparison of perforated duodenal ulcer with acute pancreatitis

| Perforated ulcer | Acute pancreatitis | |

|---|---|---|

| Age and sex | Middle-aged males | Younger males |

| Pain and peritonitis | Severe pain and board-like ridigity | Severe pain, less marked guarding, marked release tenderness |

| Vomiting | Repeated vomiting uncommon | Vomiting common and persistent |

| Dyspnoea and cyanosis | Uncommon | Common |

| Abdominal distension | Scaphoid abdomen | Mild distension common |

| Mass | Uncommon | Epigastric mass common |

Prostration and shock, dyspnoea, ventilatory insufficiency and cyanosis indicate a severe attack with poorer prognosis. Extraperitoneal fluid and blood extravasation may be indicated by staining in the flanks (Grey-Turner’s sign) or around the umbilicus (Cullen’s sign).These signs are typically delayed in onset and may not be present at the initial presentation. The common predisposing causes of severe pancreatitis are gallstones and alcohol. In alcoholic pancreatitis the patient may be agitated and confused, indicating imminent delirium tremens.

3. Perforated peptic ulcer

Signs. The clinical signs are usually unmistakable. Generalised peritonitis is present, with board-like rigidity in the epigastrium and elsewhere. The term is very appropriate and, once felt, is difficult to confuse with anything else. The abdomen is silent and loss of liver dullness to percussion may be elicited. Pulse, temperature and blood pressure are all likely to be normal. Shock does not develop until a late stage. The delayed ‘stage of reaction’ or of ‘masked’ peritonitis takes several hours to develop. This should not confuse the careful observer, as rigidity and ileus persist. More difficulty is found with a localised duodenal leak when the history is less typical and the abdominal signs are restricted to local tenderness in the upper abdomen (Ch 7.3).

5. Strangulating intestinal obstruction

Signs. Although certain clinical features can create a suspicion that strangulation is present (Box 7.1), no clinical or laboratory findings exist that exclude with certainty the possibility of strangulation. In small bowel obstruction the bowel sounds are hyperactive. Signs of local peritonitis and a palpable mass strongly suggest strangulation. A strangulated external hernia (femoral, inguinal, umbilical or incisional) will be tense, tender, irreducible and will have lost the cough impulse. Always search for a hernia, even in the patient who has had previous abdominal operations. Signs of interstitial fluid and blood volume depletion will be present when bowel obstruction has persisted for one or more days. Early shock or poor response to resuscitation suggests the presence of strangulation.

In large bowel obstruction, distension is particularly marked in the flanks and in the right iliac fossa. Signs of fluid depletion are late. The distension is predominantly gaseous and signs of shock or peritonitis suggest that perforation has occurred. Careful sigmoidoscopy may reveal the cause of the obstruction.

9. Less common causes

The pain of renal infection can mimic an acute abdomen. Associated urinary frequency, dysuria and pyuria usually suggest the diagnosis. Rupture of an inferior epigastric vessel may be associated or follow treatment with oral anticoagulants. Rectus sheath haematoma may be spontaneous or precipitated by minor trauma and can mimic an acute abdomen or appendicitis. Similarly, ‘spontaneous’ retroperitoneal haematoma can occur in anticoagulated patients and present with lateralised abdominal or flank pain.

Diagnostic plan

Imaging techniques

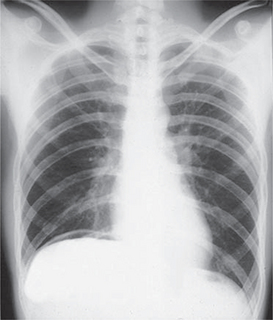

These include plain radiology, ultrasound, contrast and computed tomography (CT scan) and are very often valuable. Erect chest X-ray (Fig 7.11), together with erect and supine films of the abdomen, are indicated in nearly all patients. (For patients too moribund to undergo an erect chest X-ray, a lateral decubitus film may be requested.) These X-rays may show primary chest pathology (pneumonia) or basal changes secondary to a subdiaphragmatic condition such as pancreatitis. Free gas under the diaphragm indicates a perforated viscus, usually a perforated ulcer or perforated diverticulitis. A grossly dilated stomach may be seen in patients in diabetic coma, falsely suggesting the possibility of a surgical condition.

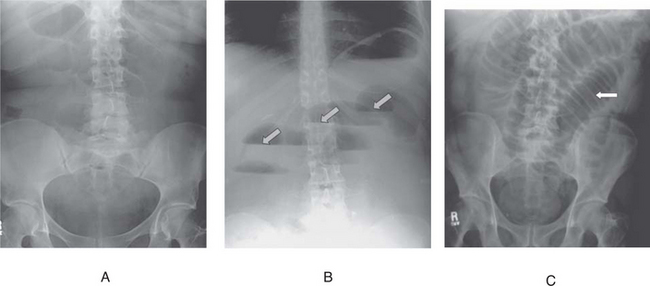

If small bowel obstruction is suspected, erect and supine views show significant distension of the small bowel with gas fluid levels and a ladder pattern (Fig 7.12). In large bowel obstruction, the colon is distended down to the site of obstruction and small bowel dilatation may coexist. If the ileocaecal valve is incompetent specific causes such as sigmoid or caecal volvulus may show localised distended large bowel loops. Gastroenteritis can be associated with small gas–fluid levels with moderate intestinal distension. Air swallowing in association with severe pain and recent injury may cause confusion. The absence of free gas does not exclude perforated viscus, nor does the absence of fluid levels in the bowel exclude strangulation. Free gas is seen in only about two-thirds of cases of perforated peptic ulcer. In appendicitis, distended bowel with fluid levels on plain X-ray often indicates a localised ileus in the right iliac fossa. Pancreatic calcification or lithiasis or a sentinel small bowel loop in the region of the pancreas or a colonic ‘cut-off’ sign may be seen in pancreatitis. More commonly, generalised ileus is present, with evidence of ascites. Distended, gas-filled, small and large bowel loops with fluid levels are present and large bowel gas extends to the rectum. Mesenteric infarction causes a diffuse small bowel ileus. In ruptured aortic aneurysm a rim of calcium may be seen in the aneurysm, particularly in the lateral decubitus films. Radio-opaque gallstones may be seen in cholecystitis (20%); urinary calculi are usually visible (80%).

Catheter angiography is rarely required, apart from the context of mesenteric vascular insufficiency.

Treatment plan

2. Acute severe (haemorrhagic) pancreatitis

Exploratory operation is occasionally unavoidable because another surgical condition (e.g. perforated ulcer, bowel obstruction, appendicitis) cannot be excluded (Box 7.2). Diagnosis is confirmed by finding an inflammatory pancreatic mass with fat necrosis and ascites (‘beef-tea’ fluid). A peritoneal dialysis catheter can be left in situ for subsequent lavage.

Treatment of pancreatitis otherwise is initially conservative:

Table 7.4 Indicators of severity of acute pancreatitis (Glasgow system)

| Factor | Level |

|---|---|

| Age | >55 years |

| Leucocytosis | >15 × 109/ L |

| Blood urea concentration | >16 mmol/L (no response to fluid administration) |

| Blood glucose concentration | >10 mmol/L in the non-diabetic patient |

| Serum albumin concentration | <32 g/L |

| Serum calcium concentration | 20 mmol/L |

| Lactate dehydrogenase | 600 IU/L |

| Aspartate aminotransferase | >100 IU/L |

| Arterial Po2 | <60 mmHg (8.0 kPa) |

3. Perforated peptic ulcer

Nasogastric suction is accompanied by early operation. On most occasions, and particularly in the poor risk case (Box 7.3), the ulcer is covered with an omental plug and peritoneal washout is performed (Fig 7.14). The patient is commenced on H. pylori eradication postoperatively and risk factors addressed. For the unusual combination of perforation with serious bleeding, or for very large ulcers, partial gastrectomy may be necessary. A perforated gastric ulcer may be a carcinoma and should be biopsied and preferably treated by definitive partial gastrectomy.

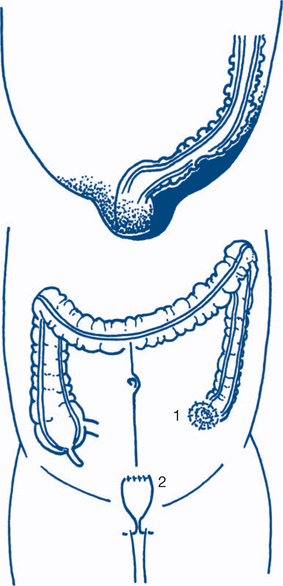

4. Perforated diverticulitis

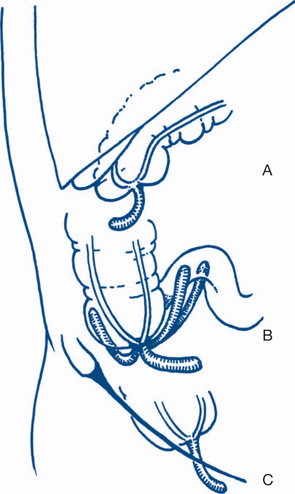

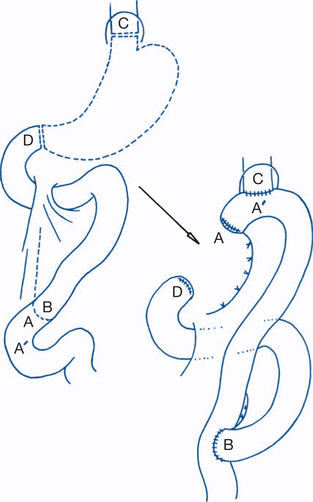

Perioperative antibiotics are given. The effected segment of colon (usually sigmoid) is resected. A restorative anastomosis is usually not performed in the presence of sepsis. The two ends of the bowel may be exteriorised as a double-barrel colostomy (Paul-Mikulicz) or, more commonly, the proximal end is brought out and the distal end is closed and left within the pelvis. This is Hartmann’s procedure (Fig 7.15). It is essential that the septic focus of diverticulitis is excised and not simply drained — drainage alone will not control infection. Later, a rectosigmoid anastomosis is performed electively when the patient is considered fit for the procedure.

6. Vascular catastrophes

For mesenteric vascular occlusion, nonviable bowel is resected at operation. If a large proportion of the small bowel is lost, it is prudent to exteriorise the ends of bowel as enterostomies. Alternatively, a planned second-look laparotomy may be performed after 24 hours to check the viability of the remaining small bowel. Anastomosis is deferred until the patient’s condition improves. If the entire small bowel is infarcted from the duodenojejunal flexure, excision and permanent intravenous feeding can be considered in younger patients without gross associated pathology.

7.3 Acute upper abdominal pain

History

2. Acute exacerbation of duodenal ulcer

The presence of H. pylori should be considered as a causative agent for gastroduodenal ulcer disease, the diagnosis confirmed and eradication therapy instituted.

3. Biliary ‘colic’ and acute cholecystitis

When rapid resolution of symptoms occurs, the patient can be investigated electively with ultrasound for gallstones. Continued pain for more than 12 hours suggests acute cholecystitis. Bacteria can be cultured from the bile in only 70% of patients with established cholecystitis. Admission to hospital is necessary for persistent pain and for associated systemic effects. In 95% of patients, acute cholecystitis results from persistent obstruction of the cystic duct by a gallstone impacted in Hartmann’s pouch. The natural history of acute cholecystitis depends upon whether the obstruction is relieved, whether there is secondary bacterial infection, the age of the patient and the presence of concurrent medical illness (particularly diabetes mellitus). Most attacks will resolve spontaneously in hospital; some progress to abscess formation and occasionally to free perforation with generalised peritonitis (Fig 7.16). Jaundice occurs in only 10% of patients and suggests stone in the bile duct, acalculous cholecystitis or gangrenous cholecystitis. Jaundice with high fever suggests ascending cholangitis.

4. Acute (oedematous) pancreatitis

In about 80% of cases acute pancreatitis is of modest severity and presents as localised acute upper abdominal pain, without systemic effects. The prognosis in these cases is good and a fatal outcome unusual. The remaining 20% of patients present with the more severe acute haemorrhagic pancreatitis with necrosis. Collapse and shock occur and the presentation is that of an acute abdomen (Ch 7.2) — a potentially lethal situation with a mortality rate of 30%.

Examination

Cholecystitis

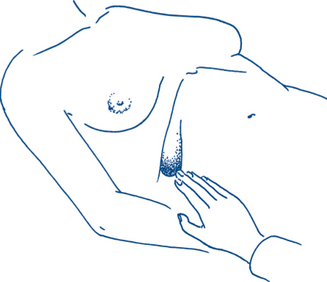

Right upper quadrant tenderness and guarding are present. Tenderness beneath the right costal margin on inspiration is characteristic (Murphy’s sign). In about a third of patients the inflamed gall bladder is palpable. A palpable mass is found more frequently after the first 24 hours; before this, the abdominal tenderness often masks the presence of the gall bladder mass (Fig 7.17). Mild fever is common, as are moderate tachycardia and leucocytosis. In contrast, patients with biliary colic have no significant findings on examination.

High fever and chills are uncommon and suggest either the presence of empyema of the gall bladder, in which case the diagnosis is incorrect, or that common duct stone with cholangitis is a complication.

Acute pancreatitis

The signs found depend upon the severity of the disease. Despite severe pain, examination of the abdomen usually reveals that guarding is not as marked as would be expected in a patient with comparable pain due to perforated ulcer. An epigastric abdominal mass may be found. A mass is due to inflammatory oedema of the pancreas, rather than to the necrotic mass with slough that occurs with more severe forms of acute haemorrhagic pancreatitis. Peripheral circulatory and respiratory failures are uncommon — these, also, are features of the more severe form of acute pancreatitis (Ch 7.2). The temperature is usually normal or slightly elevated; leucocytosis, if present, is of moderate degree. Clinical evidence of secondary basal atelectasis and pleural effusion on the left side of the chest are common. In most cases with mild disease the patient’s clinical condition rapidly settles with treatment, with complete resolution of physical signs.

Diagnostic plan

Ultrasound and CT scanning

Ultrasound is the best method of detecting gallstones in patients with acute upper abdominal pain. It is sometimes difficult to detect gallstones by ultrasound in patients with pancreatitis because the distended bowel gas of ileus makes ultrasound examination more difficult. Ultrasound is also a valuable method of detecting and following a pancreatic mass and the evolution of pseudocysts, especially in the thin patient. Ultrasound can show the increased thickness and oedema of the gall bladder wall that is a feature of acute cholecystitis and thus can be of considerable diagnostic value in patients with acalculous cholecystitis. Ultrasound is less effective in the obese patient with excess gastrointestinal gas. Occasionally in such patients, a CT scan is a better examination — CT imaging of the gall bladder is not as satisfactory as ultrasound, but CT imaging with contrast of the pancreas can be highly discriminatory in patients with acute pancreatitis.

Treatment plan

4. Acute (oedematous) pancreatitis

In gallstone pancreatitis, current opinion favours performing a cholecystectomy during the initial hospital stay so that the risk of another attack is avoided. In aged patients, endoscopic sphincterotomy may be a safer alternative initial form of treatment.

5. Less common causes

Sometimes aortic aneurysm presents with acute epigastric or left hypochondrial pain when rupture is imminent. More commonly the problem presents as an acute abdomen (Ch 7.2). An interval of several hours may exist between the first episode of self-limited bleeding and later retroperitoneal rupture.

7.4 Acute right iliac fossa pain

History and physical examination

1. Acute appendicitis

Acute appendicitis can occur in infants and the old but most cases are found during adolescence and early adult life. Appendicitis at the two extremes of age is more difficult to diagnose. The symptoms usually begin with pain that is central, symmetrical and often colicky. As with many other viscera, the early pain of appendicitis is often referred to the somatic dermatome of the midgut — around the umbilicus. The patient is often awakened in the early morning by vague abdominal discomfort progressing to central or epigastric cramping pain, followed some time later by increasing nausea, anorexia and indigestion. Neither vomiting nor diarrhoea is an early symptom. An illness starting with nausea or diarrhoea, progressing to abdominal pain, suggests that the diagnosis is gastroenteritis, not appendicitis (Table 7.2). Early rigor and high fever are also uncommon and favour another diagnosis, such as urinary tract infection. Absence of fever must not preclude the diagnosis of appendicitis. Fever is absent throughout the course of the disease in a significant number of patients with appendicitis. Within several hours the pain shifts and becomes localised in the right iliac fossa; the patient can often point to the site of tenderness with one finger. Movement and coughing increase the abdominal discomfort.

Most atypical presentations of appendicitis are due to appendicitis in an anomalously positioned appendix (Fig 7.18).

Young children and the aged tend to have a more rapid and severe course with early peritonitis or early abscess formation and poor localisation of infection. A similar natural history is often found in obese patients. Appendicitis is a particularly dangerous condition in psychiatrically disturbed patients and in infancy. One must always be aware of the possibility of appendicitis in an infant who is lethargic, irritable and difficult to examine, especially when vomiting and abdominal distension are present. The younger the patient, the more appendicitis appears to resemble gastroenteritis.

4. Gynaecological disorders

Ectopic pregnancy. Ectopic pregnancy is an important condition that can resemble acute appendicitis, particularly the subacute presentation that follows ampullary implantation. In these patients there may not be a history of missed period. On examination, as well as poorly localised tenderness in the right lower abdomen, the cervix is tender and soft and the uterus is enlarged. An elevated beta HCG is often helpful in the diagnosis.

Diagnostic plan

When doubt about the diagnosis exists, the following investigations can be performed.

Laparoscopy

In many cases a safe appendicectomy can be performed by laparoscopy. If the appendix is normal many of the other possible surgical conditions can be seen and treated laparoscopically.

Treatment plan

2. Acute mesenteric adenitis and Meckel’s diverticulitis

The diverticulum is removed and bowel continuity restored. The appendix is also removed.

6. Less common causes

These are numerous. Perforated ulcer may present with acute pain in the right iliac fossa due to gastric fluid tracking down the right paracolic gutter. Carcinoma of the right colon or caecum may present acutely, like appendicitis, with a complication such as obstruction or localised perforation. A mass in the right iliac fossa with accompanying anaemia suggests the diagnosis. Crohn’s disease may present with acute right iliac fossa pain. There is usually a history of altered bowel habit and general deterioration in health with weight loss. Occasionally acute regional ileitis (which may be the earliest phase of Crohn’s disease) presents de novo with acute right iliac fossa pain. At operation in these cases, a copious straw-coloured intraperitoneal fluid discharges on opening the peritoneum. The appendix is normal and an acutely inflamed distal ileum is found. Appendicectomy is usually necessary in these cases and, if performed with care, will not lead to a faecal fistula. If the appendix is not removed, the presence of a right iliac fossa incision may delay necessary surgery at a later date. Diverticulitis in a redundant sigmoid colon in the right iliac fossa; an isolated caecal diverticulitis or benign caecal ulcer are occasional causes of acute right iliac fossa pain. Right basal pneumonia may also present with predominantly right-sided abdominal pain and guarding. The diagnosis may be difficult, but the clue to the diagnosis is the presence of respiratory distress even though clinical signs on chest examination may be minimal. Herpes zoster (shingles) can mimic appendicitis but the pain follows the nerve root distribution. Often a heraldic vesicle will be found on careful examination, in which case non-surgical observation and review confirm the diagnosis.

7.5 Acute lower abdominal (pelvic) pain

Acute lower abdominal pain may be suprapubic or felt in one or other iliac fossa or associated with deeper pelvic pain. It is often difficult for the patient to localise or the doctor to interpret whether the site of pain is confined to the lower abdomen or extends into the pelvis. Most patients can separate pelvic and associated lower abdominal pain from anorectal or perineal pain: the latter is considered as a separate problem in Chapter 7.22. Acute right iliac fossa pain usually presents as a separate problem (Ch 7.4)

Pain secondary to spinal disease and referred along the T12 and L1 dermatome and pain from local soft tissue injury or groin hernias may occasionally give somewhat similar pain. Musculoskeletal pain rarely requires hospital admission and most musculoskeletal conditions of the lumbosacral spine and pelvis are easy to distinguish (because of the relation to posture and movement) from visceral conditions causing lower abdominal or pelvic pain. Acute renal colic (Ch 9.2) with its characteristic pattern is usually easily distinguishable. In cystitis, frequency and burning of urination dominate the clinical picture (Ch 9.3).

Conditions causing acute lower abdominal and pelvic pain separate into two main groups:

History and physical examination

1. Diverticulitis

Acute colonic peridiverticulitis results from obstruction, inflammation and sometimes localised rupture of a diverticulum. The pain is of gradual onset, its site depending upon the position of the sigmoid colon (which often lies in the pelvis) and how well localised the inflammatory process is. A history of previous bowel irregularity and lower abdominal discomfort and distension, partially relieved by defaecation, is common. Fresh rectal bleeding is not a feature of diverticular disease and when present indicates that another condition such as haemorrhoids or carcinoma is likely to be present. However, profuse rectal bleeding can occur with diverticular disease — but rarely, if ever, with acute diverticulitis (Fig 7.19). Diverticulitis adjacent to the bladder may produce dysuria. In younger patients a very similar acute clinical picture may be due to spastic colon or functional bowel disease but, more commonly, this condition causes chronic pain in the lower abdomen.

Large bowel obstruction due to diverticular disease (i.e. diverticular stricture) is uncommon. Associated small bowel obstruction, however, may occur due to adhesion of a loop of small bowel to the area of sigmoid diverticulitis.

The localised forms of disease (stage 1 or 2) present as acute lower abdominal or pelvic pain often localised to the left iliac fossa. Patients with stage 3 or 4 disease present with an acute abdomen (Ch 7.2).

2. Carcinoma of the colon

Carcinoma may sometimes mimic diverticular disease. Partial obstruction of the left colon usually develops insidiously and the presenting symptom is usually altered bowel habit rather than pain (Ch 7.20). Sometimes, however, acute deep-seated lower abdominal cramping pain is the predominant initial symptom. The pain of partial obstruction is usually felt in the hypogastrium, often more so on the left side and sometimes in the back. Complete large bowel obstruction may develop soon after the onset of colicky pain. These cases usually reveal a short history of constipation and distension, partially relieved by defaecation. Rectal bleeding may have been noted by the patient.

4. Gynaecological disorders

Acute lower abdominal and pelvic pain in a young woman immediately suggests the possibility of gynaecological disease, especially when the pain is associated with a menstrual disorder. The pain is mainly felt deep in the pelvis or suprapubically. Acute abdominal pain in pregnancy forms a special group. The causes are shown in Table 7.5.

| First trimester | Second trimester | Third trimester |

|---|---|---|

| Ectopic pregnancy | Red degeneration in fibromyoma | Premature labour |

| Abortion | Pyelonephritis and cystitis | Abruptio placentae |

| Ruptured corpus luteum | Cholecystitis | Uterine rupture |

| Liver rupture and haematoma | ||

| Appendicitis | HELP* | |

| Nonulcer dyspepsia and reflux |

* Haemolysis. Elevated liver enzymes. Low platelets. A pre-eclamptic condition presenting with acute epigastric pain.

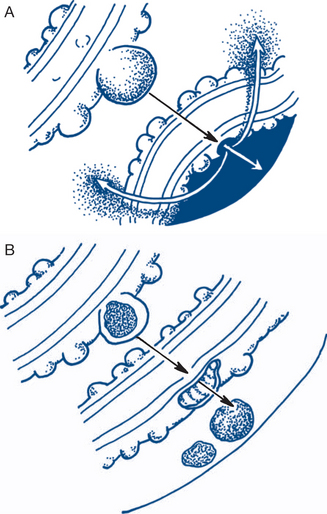

Acute rupture of an ectopic pregnancy. This presents with acute pain, which may be referred to the shoulder from diaphragmatic irritation, progressing to pallor and shock. The cervix is soft and extremely tender to palpation and dark vaginal bleeding of modest amount occurs, usually after two or three months of amenorrhoea. Ectopic pregnancy may be difficult to distinguish from appendicitis. Ectopic pregnancy with ampullary implantation has a more benign course than acute tubular rupture associated with implantation in the isthmus. A more gradual onset of lower abdominal and pelvic pain precedes dark vaginal bleeding after variable amenorrhoea (Fig 7.20). Blood also passes retrogradely into the peritoneum to collect in the pouch of Douglas forming a pelvic haematocele. The temperature may be normal or elevated. On vaginal examination dark blood may be seen escaping from the external os. Extreme tenderness elicited by movement of the soft cervix makes palpation of any tubal swelling difficult — signs that are not found with mittelschmerz.

Diagnostic plan

Laparoscopy

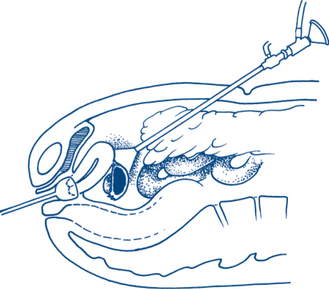

This is indicated in patients where a gynaecological disorder is suspected and will help to exclude appendicitis and diverticulitis in difficult cases (Fig 7.21).

Laparotomy is necessary for diagnosis and treatment in patients with clinical deterioration, with peritonitis or with a pelvic mass.

Treatment plan

1. Diverticulitis

Elective surgery. The indications for elective resection are:

3. Pelvic appendicitis

Early appendicectomy should be performed laparoscopically or through an iliac fossa or midline incision. The peritonium is washed out and perioperative antibiotics are given. An associated pelvic abscess will require formal drainage as well. The drainage tube is preferably brought out through a separate stab incision.

7.6 Chronic epigastric pain

Chronic epigastric pain is attended by a limited and manageable list of common causes (Table 7.6). A wide spectrum of less common causes exists.

Table 7.6 Features of the common causes of chronic epigastric pain

| Cause | Feature |

|---|---|

| Nonulcer dyspepsia | Atypical patterns |

| Gallstones | Episodic pain |

| Duodenal ulcer | Periodic or cyclical pain |

| Carcinoma of stomach | Onset of dyspepsia in a patient over 40 years |

History

2. Gallstones and chronic cholecystitis

Patients with gallstones frequently present with episodic upper abdominal pain. Biliary pain (‘colic’) begins abruptly and subsides gradually over a period of hours and is usually felt in the epigastrium or right hypochondrium. It can be postprandial or nocturnal and commonly radiates around the costal margin to the back with a sometimes severe and usually constant nature. Patients have often had a number of similar attacks requiring narcotic analgesics or admission to hospital. The pain may occasionally be felt in the left hypochondrium or precordially, making it difficult to distinguish from oesophageal pain or angina. The acute upper abdominal pain of acute cholecystitis usually leads to hospital admission (Ch 7.3) and early cholecystectomy and is related to persistent rather than transitory obstruction of the cystic duct by stone.

3. Duodenal ulcer

The Zollinger-Ellison syndrome (gastrinoma of the pancreas) should be considered when a severe and resistant ulcer diathesis is present. Features suggesting the diagnosis include ulcers situated more distally, multiple and recurrent ulcers, severe diarrhoea (found in 30% of cases) and the combination of severe upper and lower abdominal symptoms (Box 7.4).

4. Gastric ulcer

The history of patients with gastric ulcer is very similar to that of duodenal ulcer (Table 7.7). Pain, however, tends to be more severe, more loss of work occurs and relapse is more frequently triggered by analgesic agents. Relapses last longer, generally from one to two months. Food and alcohol appear to worsen the pain, which generally occurs within 30 minutes of a meal. Anorexia and weight loss are also more common. Associated gastritis is a feature of gastric ulcer and contributes to weight loss. Vomiting is more common and more likely to relieve the pain.

Table 7.7 Comparison of the clinical features of duodenal and gastric ulcers

| Features | Gastric ulcer | Duodenal ulcer |

|---|---|---|

| Onset of pain | Occurs within 30 minutes of a meal | Occurs 2–3 hours after meals — ‘hunger pain’ |

| Wakes patient at night | ||

| Relieving factors | Vomiting | Food and milk, antacids |

| Precipitating factors | Eating (may lose weight) | Smoking and other risk factors |

| Analgesics | ||

| Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs | ||

| Periodicity | 2–3-month cycle | 4–6-month cycle |

5. Carcinoma of the stomach

Complications may cause additional symptoms, depending on the site of the tumour. Nausea and vomiting can result from pyloric obstruction (10–20% of patients) or there may be dysphagia due to oesophageal obstruction (10% of patients). Haematemesis and melaena is unusual, but iron deficiency anaemia from chronic blood loss is found on investigation in almost half the patients. Anaemia may be the sole form of presentation (Ch 7.18) in a small proportion of patients.

Diagnostic plan

Contrast radiology

Distinguishing benign from malignant gastric ulcers is often difficult; endoscopy is usually necessary to obtain a definitive diagnosis. Barium swallow is the preferred initial investigation for gastrointestinal symptoms only if dysphagia is the major presenting problem and an oesophageal or pharyngeal lesion is suspected (Ch 7.12). Endoscopy will usually be required subsequently to confirm the radiological findings. Contrast study of the small bowel (small bowel enema) is indicated in the occasional patient where chronic small bowel obstruction is suspected to be the cause of epigastric pain. Abdominal CT examination with contrast is most useful when a pancreatic lesion is suspected and for the diagnosis and the definition of focal lesions in the liver. For the latter lesions, a triple phase CT angiography study can delineate lesions very clearly

Treatment plan

1. Nonulcer dyspepsia

There are two main avenues of treatment for nonulcer dyspepsia. Attention should first be given to control of gastric risk factors, particularly alcohol intake, smoking and dietary irregularity. Written instructions can be given to the patient as set down in Box 7.5. Drug treatment may also be required. Proton-pump inhibitors are superior to H2-receptor antagonists in relieving symptoms. Helicobacter pylori eradication should occur if biopsies are positive.

2. Gallstones and chronic cholecystitis

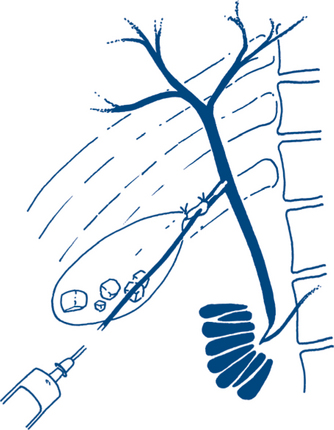

There is no satisfactory medical treatment for gallstones. Bile salts have limited usefulness and limited ability to dissolve gallstones in the long term. Shock wave lithotripsy is contraindicated. The treatment is by elective cholecystectomy after control of any concurrent disease. In about 5% of cases unsuspected stones are found in the bile duct, so operative cholangiography should be a routine (Fig 7.22). Percutaneous laparoscopic cholecystectomy is the operation of choice but open operation may be necessary if the gall bladder is very thickened or contracted or not properly visible because of chronic adhesions.

3. Duodenal ulcer

Most duodenal ulcers have a chronic, fluctuating, periodic natural history. The key decision in patients with significant and disabling symptoms is between long-term drug therapy and surgery. Medical management consists of attention to risk factors — particularly smoking, dietary irregularity, stress, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory agents, coffee ingestion and alcohol. The treatment of H. pylori involves the use of a proton pump inhibitor and two antibiotics (e.g. clarithromycin plus metronidazole). Modern medical treatments heal most ulcers.

5. Carcinoma of the stomach

Local control of the disease is best obtained by surgery (Box 7.6). Surgery should, if possible, completely excise the gastric lesion so that recurrence does not occur at this site during the life of the patient (Fig 7.23). Symptoms due to anastomotic recurrence represent a surgical failure.

Box 7.6

Management of carcinoma of the stomach

Excision of all macroscopic disease (with potential for cure) is possible in about 25% of patients.

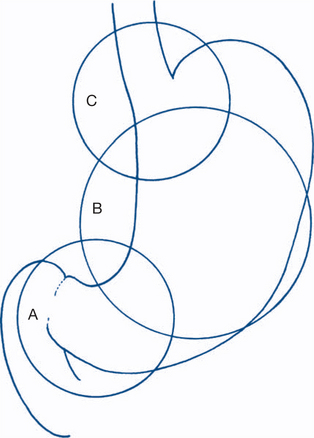

The decision as to whether the tumour is resectable usually requires laparotomy. The major reason for inability to resect the lesion is posterior fixation. Laparotomy is superior to CT scanning in deciding whether resection is feasible, especially in wasted patients where loss of fat planes makes the extent of the tumour difficult to determine on scan. Total gastrectomy (Fig 7.24) is preferred in patients who have satisfactory general health. Total gastrectomy is also indicated with diffuse or desmoplastic tumours at any site and in tumours with associated atrophic gastritis. Ivor Lewis oesophagogastrectomy is indicated in resectable carcinoma of the cardia. About half those coming to operation can have the tumour resected. Half the resections can be considered potentially curable, there being no apparent macroscopic spread beyond resected tissue. Adjuvant chemotherapy may further improve survival after resection. The total five-year survival rate in Western countries remains poor and is about 15%.

6. Less common causes

Gastrointestinal causes

Reflux oesophagitis. These patients are usually identified by the dominant presenting symptom of postural heartburn and regurgitation. Retrosternal oesophageal pain is characteristically related to swallowing. The pain may be precordial and difficult to distinguish from angina (Ch 7.11). When felt lower down — behind the xiphoid process or in the epigastrium — reflux oesophagitis can be difficult to differentiate from other causes of chronic epigastric pain. Associated symptoms of fluid regurgitation suggest that reflux oesophagitis is the primary cause of the problem. Surgery is indicated for failed medical management, especially when there are complications such as aspiration pneumonitis.

Chronic pancreatitis. Epigastric pain is often vague, deep-seated and nauseating, and may radiate through to the back. The patient characteristically assumes a sitting position with spinal flexion in an attempt to relieve pain. Weight loss is likely to be more profound if carcinoma is present. Chronic pancreatitis affects a different set of patients from acute pancreatitis, the latter presenting with acute upper abdominal pain (Ch 7.3). There is considerable overlap between acute and chronic pancreatitis, particular where the aetiological factor is alcohol. Both conditions are associated with heavy alcohol consumption. In about half the patients with chronic pancreatitis the disease presents with recurrent episodes of epigastric pain and the complications of malabsorption and diabetes should be considered.

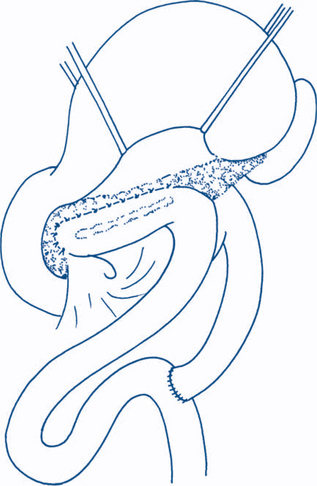

The principles of medical treatment of chronic pancreatitis include abstinence from alcohol (which is rarely effective for late disease with continuous pain), narcotic analgesics, splanchnic nerve block, nutritional support, pancreatic enzymes plus antacids and the control of diabetes (which is found in about a third of cases). Surgical treatment is indicated for intractable pain. Alcoholism should not necessarily influence the decision but indicates the need for careful preoperative preparation. Most surgeons would in fact stipulate abstinence as a prerequisite for surgery. Duodenal ulcer is often associated with chronic pancreatitis and should be excluded by endoscopy. Duct dilatation is found on ERCP in 30–40% of cases. In these patients a Roux-en-Y pancreaticojejunostomy (often combined with resection of the pancreatic head) is the surgical treatment of choice (Fig 7.25).

Carcinoma of the body of the pancreas. Management is unsatisfactory. The disease usually presents late with locally advanced disease or metastases. Careful preoperative planning, with percutaneous fine needle aspiration biopsy to establish the diagnosis and CT scanning to determine the extent of disease, is desirable. Resection is restricted to the occasional case with potentially curable disease.

Post-cholecystectomy syndrome. This term is applied to patients who complain of biliary pain, dyspepsia, flatulence and fatty food intolerance after cholecystectomy (Box 7.7). Retained common duct stone should be excluded by CT cholangiogram or MRCP. If stones are found, they are extracted with a basket after ERCP sphincterotomy. Other causes of pain, such as peptic ulcer and bile reflux gastritis, may be seen on endoscopy. Occasionally post-cholecystectomy pain may be due to stones in a cystic duct remnant. In patients who have had a cholecystectomy for biliary dyskinesia — that is, no stones were found at the original operation — the diagnosis usually proves to be functional bowel disease. Spasm of the sphincter of Oddi can produce a dilated bile duct and episodes of pain, but the results of sphincterotomy are unpredictable in these cases.

Post-gastrectomy syndromes can in most cases be treated conservatively (Table 7.8).

| Syndrome | Medical treatment | Surgical treatment |

|---|---|---|

| Dumping | Beta-blocker | Roux-en-Y bile diversion |

| Early | Small, frequent dry meals, low sugar intake, rest after meals | |

| Late | Sugar at two hours after meals | |

| Bile reflux and vomiting, with epigastric pain | Exclude recurrent ulcer | Roux-en-Y diversion plus vagotomy or stomal reconstruction |

| H2 receptor antagonist | ||

| Bile salt binding agents | ||

| High-fibre diet | ||

| Avoid risk factors | ||

| Diarrhoea | As for irritable colon | Reversal of pyloroplasty or reversed ileal loop |