CHAPTER 51 Urodynamic investigations

Introduction

Evaluation of lower urinary tract dysfunction

Symptoms of lower urinary tract dysfunction are common amongst women of all ages and are the cause of significant impairment of quality of life (QoL). The Leicestershire Medical Research Council study (Perry et al 2000) estimates that up to 26% of community-dwelling adults have clinically significant symptoms, and up to 2.4% have significant bothersome and socially disabling symptoms, which equates to more than 40 patients per general practitioner in the UK. A thorough assessment of the symptoms, their impact and the cause is key to their successful treatment. The current guidelines of the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) suggest that the initial assessment must categorize incontinence based on symptoms, and that all patients should be assessed using a 3-day diary along with a urine dipstick (National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence 2006). Initial treatment should be conservative, with urodynamics reserved for refractory or complicated symptoms.

Normal assessment prior to urodynamics includes clinical history in isolation or the additional use of structured questioning or standardized symptom questionnaires. The utility of an accurate history (primarily categorizing incontinence as stress, urge or mixed incontinence) has been confirmed as part of a health technology assessment in the UK (Martin et al 2006), and was subsequently endorsed by NICE (National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence 2006). These guidelines also highlight the role of disease-specific QoL questionnaires which may allow assessment of bothersomeness of symptoms, and these are increasingly used for the assessment of patients with urinary tract dysfunction in both clinical practice and clinical trials. The International Continence Society’s (ICS) standardization document of 2002 also states that subjective, objective and QoL endpoints should be used as three separate measures of outcome (Abrams et al 2002). Ward and Hilton (2008) demonstrated that cure rates varied from 40% to 90% depending on the definition used, highlighting the importance of defining outcome measures accurately.

Urinary symptoms

Urinary symptoms may not consistently reflect the cause of lower urinary tract dysfunction, and hence there is a need for urodynamic investigations (Cundiff et al 1997). Jarvis et al (1980) compared the results of clinical and urodynamic diagnoses for 100 women referred for investigation of lower urinary tract disorders. There was agreement in 68% of cases of urodynamic stress incontinence, but only 51% of cases of overactive bladder. Although nearly all of the women with urodynamic stress incontinence complained of symptoms of stress incontinence, 46% also complained of urgency. Of the women with overactive bladder, 26% also had symptoms of stress incontinence.

Versi et al (1991), using an analysis of symptoms for the prediction of urodynamic stress incontinence in 252 patients, achieved a correct classification of 81% with a false-positive rate of 16%. Lagro-Jansson et al (1991) showed that symptoms of stress incontinence in the absence of symptoms of urge incontinence had a sensitivity of 78%, specificity of 84% and a positive predictive value of 87%. Where stress incontinence is the only symptom reported, urodynamic stress incontinence is likely to be present in over 90% of cases (Farrar et al 1975, Hastie and Moisey 1989). Even when women who only complain of stress incontinence and who have a normal frequency/volume chart are investigated, 65% have urodynamic stress incontinence and 8% have overactive bladder (James et al 1997).

Quality-of-life assessment

Incontinence research requires that morbidity is measured by endpoints that assess different aspects and are not always independent, such as the number of micturitions and volume voided. The relationship of these endpoints to the lives of women is not well understood. For example, do fewer incontinent episodes or reduced volume of an incontinent episode improve QoL? There are probably individual factors involved which are centred around personal psychology, such as measures of hardiness or personal construct (Toozs-Hobson and Loane 2008). QoL measurement makes an attempt to standardize assessment of many aspects of these, including areas such as social, psychological, occupational, domestic, physical and sexual domains.

Wyman et al (1987) used the Incontinence Impact Questionnaire to show that women with overactive bladder experienced greater psychosocial dysfunction as a result of their urinary symptoms than women with urodynamic stress incontinence, although no relationship was found between the questionnaire score and the urinary diary or pad test results. Kobelt et al (1999) showed that the severity of symptoms of incontinence as expressed as frequency of voids and leakage correlates well with the patient’s QoL and health status, as well as the amount that they are willing to pay for a given percentage reduction in their symptoms.

The King’s Health Questionnaire is a good example of a disease-specific QoL questionnaire which incorporates questions about both bothersomeness of symptoms and QoL (Kelleher et al 1997). It was specifically designed for the assessment of women with urinary symptoms, and has been shown to have good sensitivity to clinically relevant improvement in urinary symptoms in clinical practice and clinical trials (Kobelt et al 1999). In one study, the King’s Health Questionnaire was used to assess the outcome of surgery (colposuspension) for the treatment of urodynamic stress incontinence. There was broad general agreement between objective urodynamic changes demonstrating continence as a result of surgery and symptom and QoL score improvements (Bidmead et al 2001). More recently, there have been attempts to integrate and standardize questionnaires with the International Consultation on Incontinence Modular Questionnaire (http://www.iciq.net/, Avery et al 2004) and the Electronic Personal Assessment Questionnaire (www.epaq-online.co.uk), which have the advantage of being computer based and giving an instant result.

Urodynamic Investigations

Midstream urine specimen

Urodynamic studies are associated with a 1% risk of urinary tract infection (Coptcoat et al 1988), based on the risk of catheterization, so there is no need for women to have routine prophylactic antibiotics. However, women with particular risk factors, such as diabetes, or voiding difficulties should be given prophylactic antibiotics.

Urinary diary

A urinary diary is a simple paper record of when and how much fluid a woman drinks and voids (Figure 51.1). The diary should be completed for a minimum of 3 days (National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence 2006). Leakage episodes are recorded and (ideally) the precipitating event is also noted. The documented record is more accurate than memory alone, having reasonable test–retest reliability, particularly for incontinence episodes (Wyman et al 1991). The functional capacity of the bladder is obtained and polydipsia, as a cause of polyuria, can be excluded. Unfortunately, the diary does not differentiate between the different urodynamic diagnoses (Larsson et al 1991, Larsson and Victor 1992). The urinary diary can also be used as a baseline for monitoring women undergoing bladder retraining. More recently, an electronic version has been launched commercially which ranks bladder capacity as a centile, matched for age and fluid intake (Amundsen et al 2007). This has the added advantage of an inbuilt character-recognition programme to combine the cheap cost of a paper diary with the rapid and accurate data manipulation of a computer system, and makes possible more quantitative clinical measures than are currently feasible.

Pad test

Pad tests differ according to the length of the test and the volume of fluid within the bladder. The ICS has defined a standard 1-h pad test with a 500 ml oral fluid load (Abrams et al 1988). This involves wearing a weighed towel and drinking 500 ml of water 15 min prior to starting the test. The woman performs 30 min of gentle exercise, such as walking and climbing stairs, followed by 15 min of more provocative exercise, including bending, standing and sitting, coughing, hand washing and running, if possible. The towel is then removed and reweighed. An increase in weight of more than 1 g is considered significant. Limitations of the 1-h pad test and an oral fluid load is that it is not reliable unless a fixed bladder volume is used (Lose et al 1988), with other authors suggesting that it has a poor predictive value (Constanti et al 2008) A 24-h pad test correlates well with symptoms of incontinence, has good reproducibility and is positive if the weight gain is over 4 g (Lose et al 1989, Martin et al 2006). The extended pad test is a more lengthy and objective measurement of leakage, and can be used to confirm or refute leakage in those women complaining of stress incontinence which has not been demonstrated on cystometry.

Uroflowmetry

Measurements

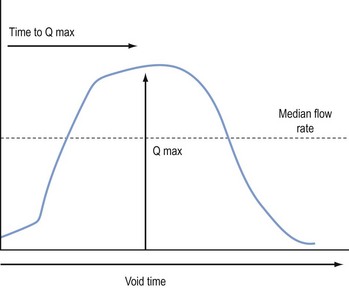

The flow rate is defined as the volume of urine (in ml) expelled from the bladder each second. The flow time is the total duration of the void and includes interruptions in a non-continuous flow. The maximum flow rate is the maximum measured rate of flow, and the average flow is the volume voided divided by the flow time. The total volume voided can be calculated from the area under the flow curve. The two most useful parameters are the maximum flow rate and the voided volume, which should ideally be greater than 150 ml. However, the Liverpool nomograms (Haylen et al 1989) will allow assessment of flow rates at a lower volume. In women with intermittent flow, the same parameters can be used but time intervals between flow episodes must be discounted. Lower volumes at presentation are more likely in the elderly and those of lower parity with a diagnosis of sensory urgency or detrusor overactivity (Haylen et al 2009).

Equipment

There are three main types of flow meter. The gravimetric transducer measures the weight of urine voided over time and this is converted to a flow rate (Figure 51.2). The rotating disc flow meter has a disc spinning at a constant speed. The voided urine slows the rotating disc. The flow rate is calculated from the amount of power needed to maintain the disc spinning at a constant speed. The capacitance flow meter has a metal strip capacitor attached to a plastic dipstick inserted vertically into the jug containing the voided urine. The rate and volume changes are measured by a change in electrical conductance across the capacitor. This is the most expensive type of flow meter, but is robust and very reliable.

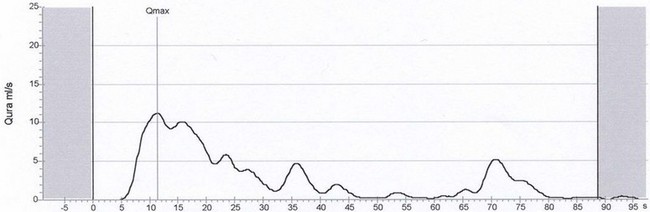

Abnormal flow rates

Nomograms for peak and average urine flow rates in women have been constructed from flow rates of 249 normal women (Haylen et al 1989). These allow comparison of a single value with a standard flow rate. A flow rate below 15 ml/s on more than one occasion is taken as abnormal when the voided volume is above 150 ml as flow rates on smaller volumes are less reliable.

A low peak flow rate and a prolonged voiding time suggest a voiding disorder (Figure 51.3). Straining can give abnormal pressure flow patterns (Figure 51.4) showing a high-pressure, low-flow pattern suggestive of obstruction. The cause of voiding dysfunction may be determined by measuring intravesical pressure simultaneously.

Cystometry

Indications

Cystometry is indicated in patients with symptoms refractory to conservative or simple treatments, or patients with complex symptoms (National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence 2006). However, the validity of the conclusions of NICE have been challenged and management without cystometry may be less accurate (Agur et al 2009).

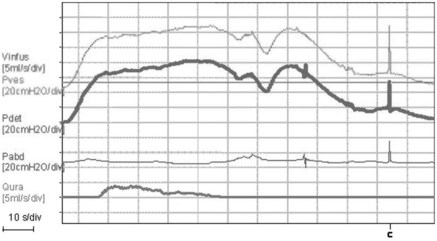

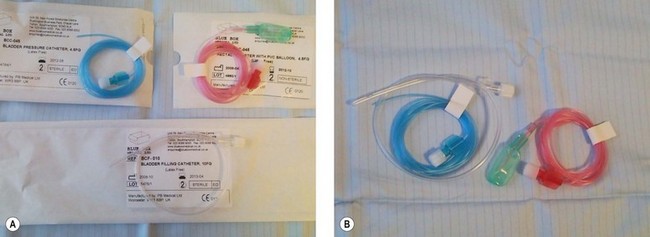

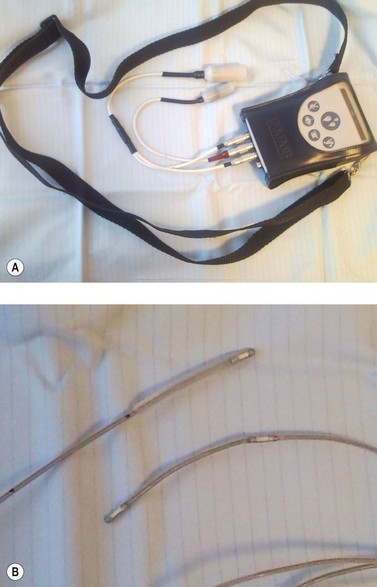

Equipment

Twin-channel cystometry requires two transducers (external or microtip), a recorder and an amplifying unit (Figure 51.5). Bladder pressure is measured using a fluid-filled line attached to an external pressure transducer or a solid-state microtip pressure catheter. A rectal catheter is required to measure abdominal pressure; this is a fluid-filled, 2-mm-diameter catheter covered with a rubber finger cot to prevent blockage with faeces when the catheter is inserted into the rectum (Figure 51.6). The upper edge of the pubic symphysis is the zero reference for all measurements, which are made in centimetres of water (cmH2O). External transducers are cheaper and less fragile, but the microtip transducer does not suffer from movement artefact.

Method

Women attend having completed a bladder diary with a comfortably full bladder. The woman then voids on the flow meter. The woman is then examined and the residual volume is noted on catheterization. During filling, the woman is asked to indicate her first desire to void and the maximal desire to void, and the volumes of these events are noted. There is evidence that women with overactivity may experience different sensations during filling compared with their stress-incontinent comparators (Digesu et al 2009). Systolic detrusor contractions and their association with urgency are noted. Precipitating factors, such as coughing or running water, are also noted. Any symptomatic detrusor pressure rise on standing is again recorded.

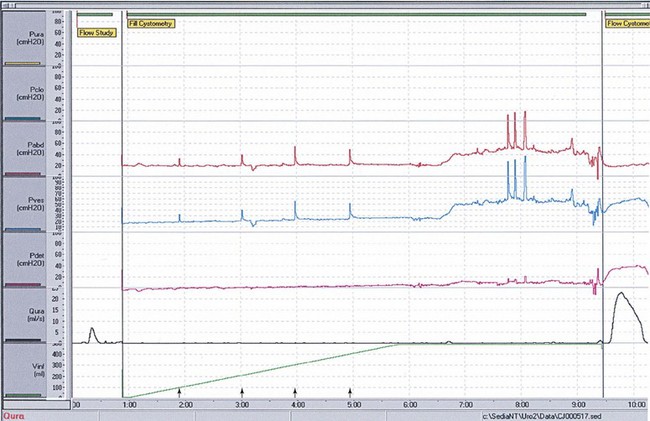

Abnormal cystometry

Urodynamic stress incontinence is defined by the ICS as leakage on coughing in the absence of a rise in detrusor pressure (Figure 51.7). It is therefore a diagnosis of exclusion, as cystometry by itself cannot determine bladder neck or urethral function; radiographic imaging or the addition of urethral function tests is required. Urodynamic detrusor overactivity is diagnosed during the filling phase if spontaneous or provoked detrusor contractions occur while the woman is attempting to inhibit micturition (Figure 51.8). Low compliance is diagnosed when the pressure rise is more than 15 cmH2O on filling the bladder with 500 ml of fluid and does not settle after filling is stopped. These parameters are all given in the ICS good practice document (www.icsoffice.org).

Laboratory urodynamics does not provide a diagnosis in 15–25% of symptomatic women. If a laboratory test fails to answer the framed question, the investigator may feel that there is a need to request a further test. A recent study has reaffirmed the importance of urodynamics in women with symptomatic prolapse where 33% had their management changed as a result of urodynamics, including 7% having their surgery changed (Jha et al 2008).

Ambulatory monitoring

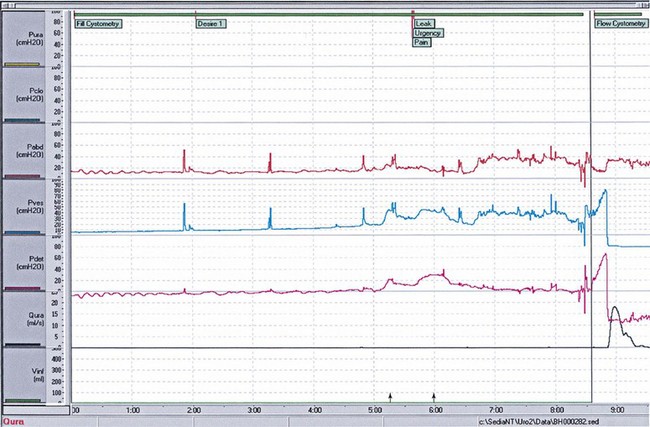

Standard twin-channel cystometry is carried out in an artificial environment over a short time frame with a filling rate that is not physiological. The test also renders the woman immobile, and bladder abnormalities produced by movement may be missed. Ambulatory urodynamic monitoring was introduced to avoid these problems, using portable digital data storage units attached to the woman for periods of several hours (van Waalwijk van Doorn et al 1991, Webb et al 1991, Anders et al 1997).

Technique

The woman wears her normal outdoor clothing and has a digital recording system (Figure 51.9). Intravesical and rectal pressures are recorded using microtip pressure transducers at a rate of 1 Hz. The ambulatory recording device can be used in conjunction with an electronic leakage detection system, and when the woman wishes to void, she connects the recorder to a flow meter and then voids. The test can last up to 6 h in clinical practice. The women are encouraged to mobilize and continue normal daily activities, including gentle exercise. Fluids should be encouraged and a minimum intake of 180 ml every 30 min is requested (Salvatore et al 1999). Antibiotic cover is not given as infection rates are less than 1%. At the end of the test, the woman is requested to attend with a full bladder and various provocative manoeuvres are carried out (similar to a standardized pad test). The woman will also keep a diary of events during the investigation, and the analysis occurs with the patient present referencing events recorded in the diary.

This investigation is available in specialist units and tends to be reserved for women in whom routine cystometry gives conflicting or unexpectedly negative results and where simple treatments have failed. This technique is more sensitive to the detection of abnormal overactive bladder in symptomatic women who had previously not been found to have an abnormality on laboratory urodynamics (Webb et al 1991, van Waalwijk van Doorn et al 1996). High rates of overactive bladder have been reported in asymptomatic controls (van Waalwijk et al 1992, Robertson et al 1994, Heslington and Hilton 1996). However, using a strict protocol for investigation and reporting, the high false-positive detection of overactive bladder in asymptomatic women is corrected (Salvatore et al 1996). There is some evidence that overactive bladder which develops after colposuspension may be occult and can be detected before surgery using ambulatory urodynamics (Khullar et al 1995). Ambulatory monitoring is time consuming and sometimes technically difficult. The equipment is expensive and fragile, which is important when women are being discharged home with the equipment in situ. Discomfort is a problem but is usually mild and more common in male than female patients. However, its utility has recently been reaffirmed (Pannek and Pieper 2008).

Radiology

Videocystourethrography

Videocystourethrography (VCU) is radiological screening of the bladder synchronized with pressure studies of the bladder, recorded with a sound commentary on video (Figure 51.10). Stanton (1988) reviewed 200 cases of urinary incontinence following failed surgery, and concluded that VCU only had an advantage over cystometry in a few selected groups of women. VCU was indicated in women complaining of postmicturition dribble, which may be due to diverticulum (although magnetic resonance imaging is the gold standard for this diagnosis) (Figure 51.11).

Postmicturition urine estimation

This useful technique obviates the need for urethral catheterization with its risk of introducing infection. It is indicated in the investigation of women with voiding difficulties, either idiopathic or before surgery, and also following postoperative catheter removal. The bladder is scanned in two planes and three diameters are measured. As the bladder only approaches a spherical shape when it is full, a correction factor has to be applied. Several different formulae have been devised, and the most common is to multiply the product of three diameters (height × width × depth) by a figure of 0.625 (Hakenberg et al 1983). This has an error rate of 21%, which is acceptable. Ultrasound machines are expensive and not always available in the community setting, in clinics or on the postoperative ward where residual volumes often need to be measured. The bladder scan is a portable ultrasound device designed for the measurement of bladder volume (Figure 51.12). The machine calculates the urine volume using preconfigured settings without the operator needing to perform any mathematical calculations, and results are similar to those obtained with complex ultrasound technology for the assessment of residual urine assessment. These become inaccurate at higher volumes, but this is not of clinical significance as the relevance of a high residual, regardless of the amount, remains. The role of this technique is limited in the immediate postoperative period in a woman with an abdominal wound, and also post partum where lochia can lead to a false-positive result.

Bladder neck position

Ultrasound scanning of the bladder neck has been used as an alternative to radiological screening, and has been reported to give equivalent information to the clinician (Brown et al 1985, Richmond et al 1986).

Ultrasound of the bladder neck has been performed using the transabdominal (White et al 1980), rectal (Shapeero et al 1983), vaginal (Hol et al 1995) and transperineal (Khullar et al 1994a) routes. The transabdominal view of the bladder neck is difficult in obese women, and there is no fixed reference point when assessing bladder neck movement. Transperineal measurement of bladder neck excursion with a specific Valsalva pressure in the antenatal period appears to predict the development of postnatal stress incontinence (King and Freeman 1998).

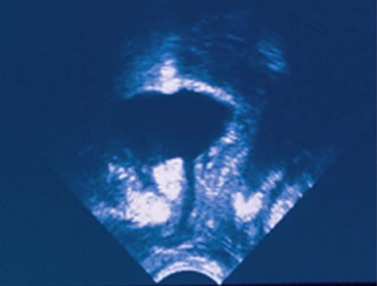

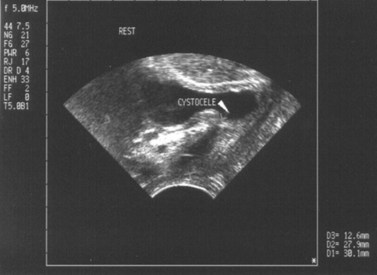

Transvaginal ultrasound

The vaginal probe has been used successfully to image the bladder neck. Descent of the bladder base, together with bladder neck opening, has been demonstrated in a majority of women with stress incontinence but not in controls (Quinn 1990). However, bladder neck opening also occurs with overactive bladder, and this may be difficult to distinguish from stress incontinence unless there is a concomitant bladder pressure recording. The bladder neck can be compressed by the transvaginal ultrasound probe, preventing urinary leakage (Wise et al 1992). The potential for distortion of the bladder neck by the probe has not been fully assessed. Transvaginal ultrasonography has been used to measure bladder wall thickness (Khullar et al 1994b, 1996a) (Figure 51.13). Women with urodynamically diagnosed overactive bladder were found to have significantly thicker bladder walls than women with urodynamic stress incontinence, and this has been proposed as a screening and diagnostic test. However, the role of this has been challenged recently (Lekskuichai and Dietz 2008).

Perineal ultrasound

Perineal scanning is the most readily available and least expensive technique. It is less likely to cause pelvic distortion, is more acceptable to women and is feasible in obese women (Figure 51.14). The technique has been shown to be as accurate as lateral chain urethrocystography in the assessment of women with failed continence surgery. The equipment is accurate, portable and available in most gynaecology departments (Gordon et al 1989). It may be of use in the determination of causes of failed continence surgery (Creighton et al 1994).

Urethral ultrasound

Urethral cysts and diverticula can be examined using ultrasound. The disadvantage of this method is that unless the opening of the diverticulum is seen directly, the two cannot be differentiated. Intraurethral ultrasonography of the urethral sphincter has been described (Schaer et al 1998) and shows an association between decreased sphincter cross-sectional area and urodynamic stress incontinence. This is not used clinically at present.

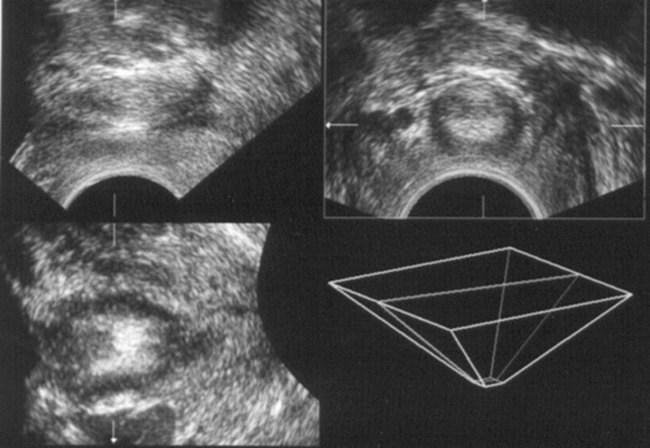

Three-dimensional ultrasound of the urethra and urethral sphincter has been described (Khullar et al 1994c). This uses a perineal probe which records 150 ultrasound ‘slices’ as the probe scans 90° on its axis. A three-dimensional image is reconstructed, giving views of the urethra and rhabdosphincter (Figure 51.15). The volume of the urethral sphincter is larger in continent women compared with women diagnosed with urodynamic stress incontinence (Athanasiou et al 1995, Khullar et al 1996b). Evidence of damage to the rhabdosphincter is present in some women with severe urodynamic stress incontinence.

Investigations of urethral function

Urethral pressure measurement

Technique

The bladder is filled with 250 ml of physiological saline, and the catheter is passed so that both sensors are within the bladder. The catheter is then connected to a catheter withdrawal mechanism set at a standard speed of 5 cm/min and a chart recorder. The static urethral pressure is the urethral intraluminal pressure along its length with the bladder at rest. The dynamic urethral pressure (the urethral closure pressure) is the difference between the maximal urethral pressure and the intravesical pressure while the woman gives a series of coughs. Women with stress incontinence have a lower urethral closure pressure than continent women, and this is directly proportional to the severity of their incontinence (Hilton and Stanton 1983).

Clinical value

Urethral pressure measurements are useful in defining physical properties; however, their value in clinical practice is not certain, with some suggesting that this offers little added value in the prediction of outcome with contemporary sling surgery (Wadie and El-Hefnawy 2009). The static urethral pressure profile is useful to detect a low-pressure urethra where the urethral pressure is less than 20 cmH2O, as these women have a 50% failure rate with conventional continence surgery. It has been suggested that they would benefit from a more obstructive procedure (Sand et al 1987).

The dynamic urethral pressure profile more closely approximates the clinical problem, but there is a large overlap for both the functional urethral length and the urethral closure pressure between normal and stress-incontinent women, and it is not possible to separate the two groups on urethral pressure profile alone. Versi (1990) compared the urethral pressure profile with VCU as the ‘gold standard’ investigation, and found that accurate diagnosis was not possible with the urethral pressure profile alone.

Leak point pressure

Leak point pressures can be detrusor or abdominal. The detrusor leak point pressure is indicated in women who have incontinence and a neuropathic condition, or those who are unable to empty their bladders (McGuire and Brady 1979).

Abdominal leak point pressure is the pressure at which leakage occurs during either a cough or a Valsalva manoeuvre. The pressure can be measured using pressure catheters in the bladder, vagina or rectum. It has been proposed as a measure of urethral resistance of the urethral sphincter to increased intra-abdominal pressure (Robinson and Brocklehurst 1983). It is highly reproducible with a strong correlation with maximum urethral closure pressure. It is not clear whether this test is useful in the evaluation of urinary incontinence.

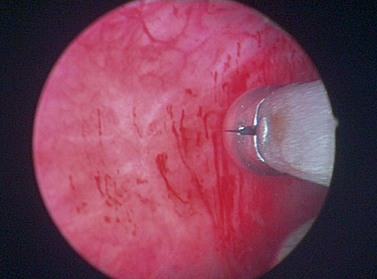

Cystourethroscopy

Technique

Bladder capacity is the volume at which filling usually stops using a 1-l bag of fluid under gravity feed. Using a 30° or 70° cystoscope, the mucosa should be inspected for abnormalities, such as signs of infection or tumour. A note is made on the state of the bladder and urethral mucosa, and the presence of normally situated ureteric orifices. Interstitial cystitis may be suggested by the presence of splits which bleed on decompression and a reduced capacity (Figure 51.16). If diverticula are present, an attempt must be made to see inside to exclude carcinoma and calculi. Bladder calculi may be present, particularly in women with neuropathic bladder and/or indwelling catheters. Abnormal areas must be biopsied.

Electrophysiological tests

Electromyography

Partial denervation has been proposed as the mechanism by which childbirth contributes to the aetiology of stress incontinence. Allen et al (1990) performed transvaginal electromyography on primiparous women before and after delivery, and detected a highly significant increase in mean motor unit potential duration which was positively associated with birth weight and length of the second stage of labour. Smith et al (1989) studied anal sphincter fibre density in women with stress incontinence and/or prolapse, and found an increased fibre density in all groups compared with normal controls.

Electromyography can be performed using surface electrodes, such as anal or vaginal plugs, and ring electrodes mounted on a urethral catheter, or it can be performed using needle electrodes inserted into the external anal sphincter or periurethral muscles. Single-fibre needles give more selective recordings and allow measurement of motor unit fibre density. A single-fibre reading is more difficult to obtain than concentric needle signals as the sampling area of the needle is less (Kreiger et al 1988), but it can be improved using ultrasound (Fischer et al 2000).

Conclusion

Urinary symptoms cause significant morbidity. Evaluation requires detailed symptom, QoL and urodynamic assessment. Whilst understanding the nature of urinary symptoms and their impact on patients’ lives is important, determining their cause requires simple and sometimes complex urodynamic investigations. Only by fully understanding the cause of lower urinary tract pathology can we hope to improve our understanding of lower urinary tract dysfunction and provide appropriate treatment. Future developments may include non-invasive cystometry using techniques such as near-infrared spectrometry to detect contractions (Macnab and Stothers 2008).

KEY POINTS

Abrams P, Blaivas JG, Stanton SL, Andersen JT. The standardisation of terminology of lower urinary tract function. Scandinavian Journal of Nephrology Supplement. 1988;114:5-19.

Abrams P, Cardozo L, Fall M, et al. The standardisation of terminology of lower urinary tract function: report from the Standardisation Sub-Committee of the International Continence Society. Neurourology and Urodynamics. 2002;21:167-178.

Agur W, Housami F, Drake M, Abrams P. Could the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence guidelines on urodynamics in urinary incontinence put some women at risk of bad outcome from stress incontinence surgery? BJU International. 2009;103:635-639.

Allen RE, Hosker GL, Smith AR, Warrell DW. Pelvic floor damage and childbirth: a neurophysiological study. British Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 1990;97:770-779.

Amundsen CL, Parsons M, Tissot B, Cardozo L, Diokno A, Coats AC. Bladder diary measurements in asymptomatic females: functional bladder capacity, frequency and 24 hour volume. Neurourology and Urodynamics. 2007;26:341-349.

Anders K, Khullar V, Cardozo LD, et al. Ambulatory urodynamic monitoring in clinical urogynaecological practice. Neurourology and Urodynamics. 1997;16:510-512.

Athanasiou S, Hill S, Cardozo LD, et al. Three dimensional ultrasound of the urethra, periurethral tissues and pelvic floor. International Urogynaecology Journal. 1995;6:239.

Avery K, Donovan J, Peters TJ, Shaw C, Gotoh M, Abrams P. ICIQ: a brief and robust measure for evaluating the symptoms and impact of urinary incontinence. Neurourology and Urodynamics. 2004;23:322-330.

Bidmead J, Cardozo L, McLellan A, Khullar V, Kelleher CJ. A comparison of the objective and subjective outcomes of colposuspension for stress incontinence in women. BJOG: an International Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 2001;108:408-413.

Brown MC, Suthurst JR, Murray A, Richmond DH. Potential use of ultrasound in place of X-ray fluoroscopy in urodynamics. British Journal of Urology. 1985;57:88-90.

Constanti E, Lazzeri M, Bini V, Gianantoni A, Mearini L, Porena M. Sensitivity and specificity of one hour pad test as a predictive value for female urinary incontinence. Urology International. 2008;81:153-159.

Coptcoat MJ, Reed C, Cumming J, Shah PJR, Worth PHL. Is antibiotic prophylaxis necessary for routine urodynamics? British Journal of Urology. 1988;61:302-303.

Creighton SM, Clark A, Pearce JM, Stanton SL. Perineal bladder neck ultrasound: appearances before and after continence surgery. Ultrasound in Obstetrics and Gynecology. 1994;14:428-433.

Cundiff GW, Harris RL, Coates KW, Bump RC. Clinical predictors of urinary incontinence in women. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 1997;177:262-266.

Digesu GA, Basra R, Khullar V, Hendricken C, Camarata M, Kelleher C. Bladder sensations during filling cystometry are different according to urodynamic diagnosis. Neurourology and Urodynamics. 2009;28:191-196.

Farrar DJ, Whiteside CG, Osborne JL, Turner-Warwick RT. A urodynamic analysis of micturition symptoms in the female. Surgery in Gynecology and Obstetrics. 1975;141:875-881.

Fischer JR, Heit MH, Clark MH, Benson JT. Correlation of intraurethral ultrasonography and needle electromyography of the urethra. Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2000;95:156-159.

Gordon D, Pearce M, Norton P, Stanton SL. Comparison of ultrasound and lateral chain urethrocystography in the determination of bladder neck descent. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 1989;160:182-185.

Hakenberg OW, Ryall RL, Langlois SL, Marshal VR. The estimation of bladder volume by sonocystography. Journal of Urology. 1983;130:249-251.

Hastie KJ, Moisey CU. Are urodynamics necessary in female patients presenting with stress incontinence. British Journal of Urology. 1989;63:155-156.

Haylen BT, Ashby D, Sutherst JR, Frazer MI, West CR. Maximum and average flow rates in normal male and female populations — the Liverpool nomograms. British Journal of Urology. 1989;64:30-38.

Haylen BT, Yang V, Logan V, Husselbee S, Law M, Zhou J. Does the presenting bladder volume at urodynamics have any diagnostic relevance? International Urogynecology Journal and Pelvic Floor Dysfunction. 2009;20:319-324.

Heslington K, Hilton P. Ambulatory monitoring and conventional cystometry in asymptomatic female volunteers. British Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 1996;103:434-441.

Hilton P, Stanton SL. Urethral pressure measurement by microtransducer: the results in symptom-free women and in those with genuine stress incontinence. British Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 1983;90:919-933.

Hol M, van Bolhuis C, Vierhout ME. Vaginal ultrasound studies of bladder neck mobility. British Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 1995;102:47-53.

James MC, Jackson SL, Shepherd AM, et al. Can overactive bladder really be discounted with a history of pure stress urinary incontinence. International Urogynecology Journal. 1997;8:S53.

Jarvis GJ, Hall S, Stamp S, Millar DR, Johnson A. An assessment of urodynamic examination in incontinent women. British Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 1980;87:893-896.

Jha S, Toozs-Hobson P, Parsons M, Gull F. Does preoperative urodynamics change the management of prolapse? Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2008;28:320-322.

Kelleher CJ, Cardozo LD, Khullar V, Salvatore S. A new questionnaire to assess the quality of life of urinary incontinent women. British Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 1997;104:1374-1379.

Khullar V, Abbott D, Cardozo LD, et al. Perineal ultrasound measurement of the urethral sphincter in women with urinary incontinence: an aid to diagnosis. British Journal of Radiology. 1994;54:134-135.

Khullar V, Salvatore S, Cardozo LD, Kelleher CJ, Bourne TH. A novel technique for measuring bladder wall thickness in women using transvaginal ultrasound. Ultrasound in Obstetrics and Gynecology. 1994;14:220-223.

Khullar V, Salvatore S, Cardozo LD, et al. Three dimensional ultrasound of the urethra and urethral pressure profiles. International Urogynaecology Journal. 1994;5:319.

Khullar V, Salvatore S, Cardozo L, Yip A, Kelleher CJ, Hill S. Prediction of the development of overactive bladder after colposuspension. Neurourology and Urodynamics. 1995;14:486.

Khullar V, Cardozo L, Salvatore S, Hill S. Ultrasound: a noninvasive screening test for overactive bladder. British Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 1996;103:904-908.

Khullar V, Athanasiou S, Cardozo L, Salvatore S, Kelleher CJ. Urinary sphincter volume and urodynamic diagnosis. Neurourology and Urodynamics. 1996;15:334-336.

King JK, Freeman RM. Is antenatal bladder neck mobility a risk factor for postpartum stress incontinence? British Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 1998;105:1300-1307.

Kobelt G, Kirchberger I, Malone-Lee J. Review. Quality-of-life aspects of the overactive bladder and the effect of treatment with tolterodine. British Journal of Urology. 1999;83:583-590.

Krieger MS, Gordon D, Stanton SL. Single fibre EMG — a sensitive tool for evaluation of the urethral sphincter. Neurourology and Urodynamics. 1988;7:239-240.

Lagro-Jansson AL, Debruyne FM, van Weel C. Value of patient’s case history in diagnosing urinary incontinence in general practice. British Journal of Urology. 1991;67:569-572.

Larsson G, Abrams P, Victor A. The frequency/volume chart in overactive bladder. Neurourology and Urodynamics. 1991;10:533-543.

Larsson G, Victor A. The frequency/volume chart in genuine stress incontinent women. Neurourology and Urodynamics. 1992;11:23-31.

Lekskulchai O, Dietz H. Detrusor wall thickness as a test for detrusor overactivity in women. Ultrasound in Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2008;32:535-539.

Lose G, Rosenkilde P, Gammelgaard J, Schroeder T. Pad-weighing test performed with standardised bladder volume. Urology. 1988;32:78-80.

Lose G, Jorgensen L, Thunedborg P. 24 hour home pad weighing test versus 1 hour ward test in the assessment of mild stress incontinence. Acta Obstetrica et Gynecologica Scandinavica. 1989;68:211-215.

Macnab AJ, Stothers L. Development of near-infrared spectroscopy instrument for applications in urology. Canadian Journal of Urology. 2008;15:4233-4240.

Martin JL, Williams KS, Abrams KR, et al. Systematic review and evaluation of methods of assessing urinary incontinence. Health Technology Assessment. 2006;10:1-132. iii–iv

McGuire EJ, Brady S. Detrusor sphincter dyssynergia. Journal of Urology. 1979;21:774-777.

National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. Urinary Incontinence: the Management of Urinary Incontinence in Women. Clinical Guideline 40. NICE, London, 2006.

Pannek J, Pieper P. Clinical usefulness of ambulatory urodynamics in the diagnosis and treatment of lower urinary tract dysfunction. Scandinavian Journal of Urology and Nephrology. 2008;42:428-432.

Perry S, Shaw C, Assassa P, et al. An epidemiological study to establish the prevalence of urinary symptoms and felt need in the community: the Leicestershire MRC Incontinence Study. Leicestershire MRC Incontinence Study Team. Journal of Public Health Medicine. 2000;22:427-434.

Quinn MJ. Vaginal ultrasound and urinary stress incontinence. Contemporary Reviews in Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 1990;2:104-110.

Richmond DH, Sutherst JR, Brown MC. Screening of the bladder base and urethra using linear array transrectal ultrasound scanning. Journal of Clinical Ultrasound. 1986;14:647-651.

Robertson AS, Griffiths CJ, Ramsden PD, Neal DE. Bladder function in healthy volunteers: ambulatory monitoring and conventional urodynamic studies. British Journal of Urology. 1994;73:242-249.

Robinson JM, Brocklehurst JC. Emepronium bromide and flavoxate hydrochloride in the treatment of urinary incontinence associated with overactive bladder in elderly women. British Journal of Urology. 1983;55:371.

Salvatore S, Khullar V, Cardozo L, et al. Controlling for artefacts on ambulatory urodynamics. Neurourology and Urodynamics. 1996;15:272-273.

Salvatore S, Khullar V, Cardozo L, Anders K, Digesu GA, Bidmead J. Ambulatory urodynamics: do we need it? Neurourology and Urodynamics. 1999;18:257-258.

Sand PK, Bowen LW, Panganiban R, Ostergard DR. The low pressure urethra as a factor in failed retropubic urethropexy. Obstetrics and Gynecology. 1987;69:399-402.

Schaer GN, Schmid T, Peschers U, Delancey JO. Intraurethral ultrasound correlated with urethral histology. Obstetrics and Gynecology. 1998;91:60-64.

Shapeero LG, Friedland GW, Perkash I. Transrectal sonographic voiding cystourethrography: studies in neuromuscular bladder dysfunction. American Journal of Roentgenology. 1983;141:83-90.

Smith AR, Hosker GL, Warrell DW. The role of partial denervation of the pelvic floor in the aetiology of genitourinary prolapse and stress incontinence of urine. A neurophysiological study. British Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 1989;96:24-28.

Stanton SL. Videocystourethrography: its role in the assessment of incontinence in the female. Neurourology and Urodynamics. 1988;7:172-173.

Toozs-Hobson P, Loane K. Why successful treatments fail. Journal of the Association of Chartered Physiotherapists in Women’s Health. 2008;102:4-7.

van Waalwijk van Doorn ES, Remmers A, Janknegt RA. Extramural ambulatory urodynamic monitoring during natural filling and normal daily activities: evaluation of 100 patients. Journal of Urology. 1991;146:124-131.

van Waalwijk van Doorn ES, Remmers A, Janknegt RA. Conventional and extramural ambulatory urodynamic testing of the lower urinary tract in female volunteers. Journal of Urology. 1992;47:1319-1326.

van Waalwijk van Doorn ES, Meier AH, Ambergen AW, Janknegt RA. Ambulatory urodynamics: extramural testing of the lower and upper urinary tract by Holter monitoring of cystometrogram, uroflowmetry, and renal pelvic pressures. Urologic Clinics of North America. 1996;23:345-371.

Versi E. Discriminant analysis of urethral pressure profilometry data for the diagnosis of genuine stress incontinence. British Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecolology. 1990;97:251-259.

Versi E, Cardozo L, Anand D, Cooper D. Symptoms analysis for the diagnosis of genuine stress incontinence. British Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 1991;98:815-819.

Wadie BS, El-Hefnawy AS. Urethral pressure measurement in stress incontinence: does it help? International Urology and Nephrology. 2009;41:491-495.

Ward KL, Hilton P. Tension-free vaginal tape versus colposuspension for primary urodynamic stress incontinence: 5-year follow up. BJOG: an International Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 2008;115:226-233.

Webb RJ, Ramsden PD, Neal DE. Ambulatory monitoring and electronic measurement of urinary leakage in the diagnosis of overactive bladder and incontinence. British Journal of Urology. 1991;68:148-152.

White RD, McQuown D, McCarthy TA, Ostergard DR. Real-time ultrasonography in the evaluation of urinary stress incontinence. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 1980;138:235-237.

Wise BG, Burton G, Cutner A, Cardozo LD. Effect of vaginal ultrasound probe on lower urinary tract function. British Journal of Urology. 1992;70:12-16.

Wyman JF, Harkins SW, Choi SC, Taylor JR, Fantl JA. Psychosocial impact of urinary incontinence in women. Obstetrics and Gynecology. 1987;70:378-381.

Wyman JF, Elswick RK, Wilson MS, Fantl JA. Relationship of fluid intake to voluntary micturitions and urinary incontinence in women. Neurourology and Urodynamics. 1991;10:132-143.