116 Urinary Tract Obstruction

Several definitions may be encountered when considering urinary tract obstruction:

Epidemiology

Epidemiology

Urinary tract obstruction is a common disorder. On autopsy, 3.1% of adults have hydronephrosis.1 Data from the Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project’s National Inpatient Sample (based on ICD-9 codes) indicate that 1.75% of all hospital discharges are complicated by either hydronephrosis or obstruction.2 When hydronephrosis is excluded, urinary tract obstruction occurs in approximately 1% of hospital discharges.2 Urinary tract obstruction accounts for approximately 10% of community-acquired acute kidney failure3–5 and is a factor in 2.6% of acute kidney failure cases in the intensive care setting.6

Etiology

Etiology

Congential Causes

Congenital UPJO is usually due to disease intrinsic to the urinary tract. Often an adynamic segment of ureter results in failure of peristalsis at the ureteropelvic junction (UPJ).7 Ureteral kinks or valves are another intrinsic cause of UPJO. Potential extrinsic causes of UPJO include abnormal rotation of the kidney during development, leading to ureteral compression and entrapment of the ureter by blood vessels, although significant controversy exists regarding the latter.7,8

Upper Urinary Tract Obstruction

Intrinsic Causes

Intraluminal Causes

Obstruction at the level of the renal tubules may be due to crystal-induced disease, uric acid nephropathy (as in the tumor lysis syndrome), or cast nephropathy due to multiple myeloma. Crystal-induced nephropathy has been classically described with sulfadiazine, acyclovir, indinavir, triamterene, and methotrexate.9 Newer literature also implicates orlistat10 and ciprofloxacin.11

Nephrolithiasis is a common cause of upper urinary tract obstruction at the level of the ureter, with the size of the stone determining the likelihood of obstruction. Stones ≤2 mm, 3 mm, 4 to 6 mm and larger than 6 mm will pass spontaneously 97%, 86%, 50%, and 1% of the time, respectively.12 Typically the obstruction occurs at one of the three narrowest portions of the ureter: the UPJ, the ureterovesicular junction (UVJ), or at the point where the ureter crosses over the pelvic brim. The obstruction is usually, but not always, acute and symptomatic. Neoplasms, blood clots, and sloughed renal papillae are rarer causes of intrinsic obstruction at the level of the ureter.

The causes of intraluminal obstruction at the level of the bladder are similar to those affecting the ureter, with urolithiasis, blood clots, and neoplasms being most common. Worldwide, infection with Schistosoma hematobium with resulting fibrosis is a common cause of bladder obstruction.13 Although rare in industrialized nations, it should be suspected in patients from endemic areas such as Africa and the Middle East.

Intramural Causes

Obstruction due to intramural causes is most often seen in the lower urinary tract. Disorders affecting the neuromuscular control of bladder emptying, such as cerebrovascular accidents,14 spinal cord injury,15 multiple sclerosis,16 and diabetic neuropathy17 may lead to bladder outlet obstruction. Multiple medications, including anticholinergics, opioid analgesics, nonsteroidal antiinflammatory agents, α-adrenoreceptor antagonists, benzodiazepines, and calcium channel blockers have also been associated with urinary retention.18 Stricture of the urethra may also lead to obstruction.

Extrinsic Compression

Pregnancy is typically associated with right-sided dilation of the renal pelvis, calyx, and ureter. Hormonal mechanisms and mechanical compression from an enlarging uterus and an enlarging ovarian vein plexus have been implicated in these changes.19 Clinically meaningful obstruction from the gravid uterus is extremely rare.

Malignancies may cause obstruction by several different mechanisms. Local ureteric compression may be seen in metastatic cancers of the cervix, bladder and prostate, as well as with expanding retroperitoneal soft-tissue masses. Alternatively, the ureters may be compressed or encased by metastatic retroperitoneal lymphadenopathy from a distant primary.20

Retroperitoneal fibrosis may lead to obstruction of one or both ureters via inflammation. It is an uncommon disorder, with a reported incidence rate of 1.3 case per million population and a male/female ratio of 3.3 : 1.21 Although the majority of these cases are idiopathic (>75%),22 numerous conditions are suspected to cause retroperitoneal fibrosis, including malignancies, medications, infection, trauma, or radiation.23 Treatment of idiopathic retroperitoneal fibrosis is initially with steroids, but recurrences are common. Case reports describe the use of cyclophosphamide, azathioprine, colchicine, mycophenolate, or tamoxifen for treatment relapses or steroid-resistant disease, although conclusive data are absent.22 Abdominal aortic aneurysms (AAA) may also cause obstruction due to compression of the ureter or via inflammation. A recent series evaluated 999 cases of inflammatory AAA and found preoperative hydronephrosis in 7.4%.24

The etiology of urinary tract obstruction is summarized in Box 116-1.

Clinical Presentation

Clinical Presentation

Pain

Acute ureteral obstruction often presents with severe flank pain, otherwise known as renal colic. This is usually due to urolithiasis but may be due to other causes of ureteral obstruction (see earlier). Obstruction causes increased intraluminal pressure and spasm of the ureteral muscles, which are responsible for the colicky pain.25 Partial ureteral obstruction may present with a chronic dull pain. Bladder outlet obstruction may lead to distention and subsequent abdominal discomfort.

Lower Urinary Tract Symptoms

Obstruction of the lower urinary tract often presents with some or all of a predictable constellation of symptoms known collectively as lower urinary tract symptoms, or LUTS. LUTS include voiding symptoms (difficulty urinating, incomplete emptying), postmicturition symptoms (post-void dribbling), and storage symptoms (urgency, frequency, hesitancy, incontinence).26 Alternatively, patients with lower urinary tract obstruction may be asymptomatic.

Infection

The urinary retention associated with lower urinary tract obstruction provides an excellent culture medium for bacteria. Patients may present with cystitis, pyelonephritis, or sepsis. An obstructing renal stone may also be a nidus for infection. Recurrent infection should raise suspicion for possible anatomic abnormalities, especially in men. In one study, 25 out of 83 men (30%) with a febrile urinary tract infection (UTI) had anatomic lesions in the lower urinary tract, supporting imaging of the lower tract in men with this presentation.27 More recent data refute this finding in men younger than 45 years old.28

Imaging in Urinary Tract Obstruction

Imaging in Urinary Tract Obstruction

Plain Abdominal Radiography

Abdominal radiography (kidney, ureter, and bladder [KUB]) is often the first imaging modality preformed in patients with acute flank pain. Although most stones are composed of calcium and should in theory be visible, only 59% of stones are detected on plain film.29 Compared to CT scanning, the sensitivity and specificity of abdominal films were 45% to 59% and 77%, respectively.29 Further, plain films may not always be able to differentiate phleboliths from calculi. This limits the utility of plain abdominal films to the diagnosis of recurrent disease in those with known radioopaque stones.

Ultrasound

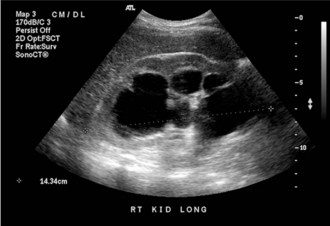

Ultrasound (US) is inexpensive, does not expose the patient to radiation, and is typically readily available. Its accuracy in detecting hydronephrosis makes US a good screening tool for obstruction in the patient with unexplained kidney failure, or the patient with suspected lower urinary tract obstruction (Figure 116-1). US has been largely superseded by noncontrast CT in the detection of nephrolithiasis and stone-related obstruction. When CT is used as a reference, US has a sensitivity of 24% and a specificity of 90% for the detection of kidney stones and is likely to miss those less than 3 mm.30 Another disadvantage of US compared to CT is that bowel gas may obscure visualization of the ureters.31 Thus despite its ability to detect hydronephrosis, US may be limited in its ability to demonstrate the cause or site of an obstruction. Other conditions such as peripelvic cysts and renal artery aneurysms may mimic hydronephrosis on US.31 These conditions are easily distinguished via CT scanning.

Computed Tomography

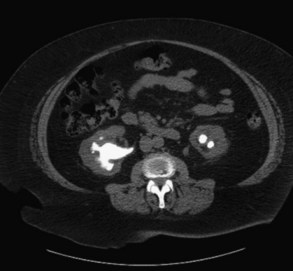

The major utility of CT scanning as it relates to urinary tract obstruction is in the evaluation of acute flank pain and suspected nephrolithiasis (Figure 116-2). In this setting, CT offers a sensitivity of 96% and a specificity of 98% for detection of stones.32 The retroperitoneum is also well visualized, making CT ideal to detect retroperitoneal fibrosis or obstruction due to retroperitoneal lymphadenopathy. In addition to defining the anatomy of the collecting system, CT has the added benefit of visualizing other organ systems, thereby providing information regarding other conditions in the differential diagnosis of acute flank pain.

Figure 116-2 Bilateral nephrolithiasis on an unenhanced computed tomography (CT) scan. Note the staghorn appearance on the left.

One concern raised with CT scanning is the high radiation dose administered. Each CT scan is equivalent to approximately 10 KUBs.33 Recent work has focused on lower-dose radiation protocols. One study found that lower-dose radiation CT scan (equivalent to that of a plain film) had a sensitivity of 97% and a specificity of 96% for the diagnosis of acute renal colic when compared with standard dose. The lower-dose CT was inferior at detecting stones less than 3 mm in size,34 which may impair its ability to diagnose noncollecting system pathology.

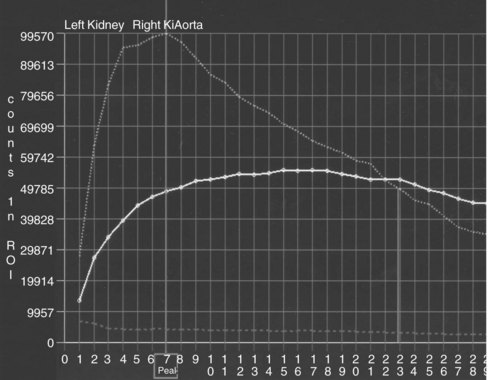

Isotope Renography

In conventional renography, radiographic tracers are injected into the patient’s blood stream, and renal uptake and excretion are measured with a scintillation counter (Figure 116-3). This test provides functional information via demonstration of decreased excretion in the obstructed kidney. The sensitivity of the test may be enhanced by administering a loop diuretic prior to the scan. The increased urine flow may unmask an occult obstruction. Isotope renography may be used if obstruction is suspected clinically but hydronephrosis is absent, or to diagnose a nonobstructive cause of hydronephrosis. In this case, excretion will be normal despite the presence of the hydronephrosis. Isotope renography does not provide anatomic information.

Intravenous Urography

Intravenous urography (IVU), in which the collecting system is imaged after the administration of intravenous (IV) contrast, used to be the study of choice for patients with acute flank pain. The need to administer nephrotoxic IV contrast and the delay in obtaining information render IVU less attractive than a CT scan.32

Retrograde Pyelography

CT scanning and US have largely superseded retrograde pyelography for the diagnosis of obstruction. Retrograde pyelography may be indicated when obstruction is highly suspected on clinical grounds, the US is negative for hydronephrosis, and the patient is unable to receive IV contrast.1

Pathophysiology of Obstruction

Pathophysiology of Obstruction

Changes in Renal Blood Flow and Tubular Hydrostatic Pressure

Over the last 3 decades, various animal models have demonstrated the pattern of renal blood flow and tubular hydrostatic pressure over time with obstruction. The initial renal response to obstruction follows a triphasic pattern.35 During the first 2 hours of obstruction, there is an initial increase in both renal blood flow and ureteral pressure. This is followed by a brief (2-3 hour) period in which renal blood flow declines due to increased afferent arteriolar resistance, yet ureteral pressures continue to rise. Ultimately the decrease in renal blood flow leads to a decrease in ureteral pressure, with the pressure returning to normal levels by 10 to 12 hours after obstruction.35 Unresolved obstruction will lead to persistent afferent arteriolar constriction and a sustained decrease in both renal blood flow and glomerular filtration rate (GFR).

The mediators of the hemodynamic responses are still under investigation. Prostaglandins may be involved in the initial vasodilation and increased blood flow, as this can be prevented with the prostaglandin inhibitor, indomethacin.36 The subsequent vasoconstriction is thought to be due to a decrease in available nitric oxide resulting from decreased nitric oxide synthetase substrate.35 In support of this theory are animal studies showing that the decrease in renal blood flow and GFR after obstruction may be attenuated with the administration of L-arginine, a nitric oxide precursor.37 The renin-angiotensin system, in particular angiotensin II (AT II), has also been implicated as an important mediator of renal vasoconstriction during obstruction.38 Identification of these mediators may result in future treatment strategies for patients with urinary tract obstruction.

Tubular Atrophy and Fibrosis

As with all long-standing kidney diseases, prolonged obstruction is associated with the development of tubular atrophy and interstitial fibrosis. Fibrosis results from an imbalance between extracellular matrix deposition and degradation. In urinary tract obstruction, there is simultaneous overproduction of profibrotic and underproduction of antifibrotic agents. Prominent among the former is AT II. In addition to its vasoconstrictive properties, AT II also has many profibrotic actions, including up-regulation of several other profibrotic mediators such as transforming growth factor beta-1 (TGF-β1), tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α), and nuclear factor kappa B (NFκB).39 Conversely, the activities of metalloproteinases and plasminogen activating inhibitor-1, both antifibrotic, are decreased during obstruction.38,39

The tubular atrophy and loss of renal mass seen with obstruction are mainly due to apoptosis, which may begin as early as 4 days after obstruction.39 Many mediators are involved including, potentially, AT II.39 Given the importance of the renin-angiotensin system in promoting renal injury after obstruction, antagonizing AT II would appear to be a viable strategy to attenuate injury. Although human data are lacking, animal data show benefit, provided the intervention is done after renal development is complete.38

Sodium Reabsorption

Upon release of a bilateral obstruction, sodium excretion increases five to nine times that of normal.40 Because the GFR is also decreased due to the obstruction, fractional excretion of sodium may be 20 times higher than normal.40 Clinically, this failure of sodium reabsorption may manifest as hypovolemia.

Animal studies have provided some insights as to the mechanisms of the abnormal sodium handling. Sodium reabsorption in the kidney is accomplished by various apical membrane transporters, which are coupled to the basolateral sodium-potassium ATPase. Many of these transporters, including the sodium/proton exchanger, sodium-phosphate cotransporter, sodium-potassium-2 chloride cotransporter, and the thiazide-sensitive cotransporter are down-regulated during and after release of obstruction.41 Recent studies suggest that the amiloride-sensitive epithelial sodium channel may be down-regulated as well.42 In addition to the down-regulation of transporters, up-regulation of atrial natriuretic peptide, a potent stimulus for sodium excretion, has been demonstrated during and after release of bilateral obstruction.43

Renal Water Handling

In addition to the effects of abnormal sodium reabsorption on water metabolism in the postobstructed kidney, animal data have demonstrated a direct role of antidiuretic hormone in the concentrating defect as well. Many studies have shown a down-regulation of aquaporins in the obstructed kidney,44–47 which may persist for weeks, accompanied by a long-term defect in urinary concentration.44 Clinically, this inability to conserve water may manifest as nephrogenic diabetes insipidus and hypernatremia.

Acid-Base and Potassium Balance

Obstruction may be associated with an inability to excrete acid. Acid-base balance is accomplished by reclamation of filtered bicarbonate and excretion of acid, either as titratable acidity (buffering of hydrogen ions by phosphates, sulfates, and other buffers) or by ammonium excretion. Clinically, obstructed or postobstruction patients may have a hyperkalemic, hyperchloremic metabolic acidosis. Although this may be due solely to the decreased GFR, some patients have persistent metabolic abnormalities long after the release of obstruction and stabilization of GFR.48 Human data reveal several pathophysiologic mechanisms. The majority of patients studied had a distal renal tubular acidosis in which systemic acidosis did not lower the urinary pH below 5.5.48 Abnormalities in sodium transport in the distal nephron (see earlier) may render this tubular segment unable to generate the lumen negative transepithelial difference needed for proton excretion—a so-called voltage-dependent defect.49 This voltage defect also leads to potassium retention and clinically apparent hyperkalemia. Other patients were able to acidify their urine to a pH of below 5.5. These patients had low plasma levels of aldosterone with subsequent hyperkalemia—a typical type IV renal tubular acidosis (RTA).48 The underlying mechanism in this case is decreased ammoniagenesis, most likely due to the hyperkalemia, although the hypoaldosteronism may also contribute.49 Patients with a type IV RTA retain the ability to excrete acid (via titratable acidity) and usually have a mild, self-limited acidosis, whereas those with a distal RTA cannot excrete acid, and the resultant acidosis may be severe.

Recent animal studies have demonstrated down-regulation of key renal acid-base transporters in urinary tract obstruction, including the cortical and medullary sodium hydrogen exchanger and several basolateral sodium-bicarbonate transporters.50

Other Tubular Functions

After release of bilateral obstruction, phosphorus excretion rises proportionally to sodium excretion.40 This may be mediated by a decrease in the number of proximal sodium phosphate cotransporters.41 Magnesium excretion also rises, likely from decreased absorption in the thick ascending loop of Henle, due to a decrease in transepithelial voltage difference created by the decreased sodium-potassium-2 chloride cotransporter activity.40 Calcium handling after obstruction is unclear and differs depending upon species studied.40

Recovery of Kidney Function

Recovery of Kidney Function

Whether or not an obstructed kidney will regain function is of paramount importance to the clinician and may dictate whether aggressive interventions are indicated, or if the affected kidney should be removed. Unfortunately, data addressing this question, particularly human data, are scant. Currently there are no methods available which reliability predict kidney recovery after relief of an obstruction,40 although one recent study found that a GFR of less than 10 mL/min in the obstructed kidney and abnormal renal perfusion (determined via isotope renography) predicted poor recovery in patients with unilateral ureteral occlusion.51

Animal studies demonstrate that the likelihood of renal recovery diminishes with longer duration of obstruction.40 Even with recovery of GFR, there may be ongoing injury and progressive long-term kidney damage after release of obstruction, likely due to interstitial fibrosis associated with prolonged urinary tract obstruction.52 In humans, the cutoff point at which renal function is unlikely to return has not been determined, and partial recovery has been seen even after months of obstruction,53 suggesting that all obstructions be relieved and followed by serial determinations of kidney function. If desired, a kidney biopsy may be done to assess the degree of interstitial fibrosis and provide prognostic information.

Key Points

Shokeir AA. Renal colic: new concepts related to pathophysiology, diagnosis and treatment. Curr Opin Urol. 2002;12:263-269.

Fowler K, Locken J, Duchesne J, Willamson M. US for detecting renal calculi with nonenhanced CT as a reference standard. Radiology. 2002;222:109-113.

Vaughan JED, Marion D, Poppas DP, Felsen D. Pathophysiology of unilateral ureteral obstruction: studies from Charlottesville to New York. J Urol. 2004;172:2563-2569.

Chevalier R, Thornhill B, Forbes M, Kiley S. Mechanisms of renal injury and progression of renal disease in congenital obstructive nephropathy. Pediatr Nephrol. 2010;25:687-697.

Li C, Wang W, Kwon T-H, Knepper MA, Nielsen S, Frokiaer J. Altered expression of major renal Na transporters in rats with bilateral ureteral obstruction and release of obstruction. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2003;285:F889-F901.

1 Tseng TY, Stoller ML. Obstructive Uropathy. Clin in Geriat Med. 2009;25(3):437-443.

2 Healthcare cost and utilization project. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality 2007 http://hcupnet.ahrq.gov/ Accessed January 18, 2010

3 Liano F, Pascual J. Epidemiology of acute renal failure: A prospective, multicenter, community-based study. Kidney Int. 1996;50(3):811-818.

4 Obialo CI, Okonofua EC, Tayade AS, Riley LJ. Epidemiology of De Novo Acute Renal Failure in Hospitalized African Americans: Comparing Community-Acquired vs Hospital-Acquired Disease. Arch Intern Med. May 8, 2000;160(9):1309-1313.

5 Wang Y, Cui Z, Fan M. Hospital-Acquired and Community-Acquired Acute Renal Failure in Hospitalized Chinese: A Ten-Year Review. Renal Failure. 2007;29(2):163-168.

6 Uchino S, Kellum JA, Bellomo R, et al. Acute Renal Failure in Critically Ill Patients: A Multinational, Multicenter Study. JAMA. August 17, 2005;294(7):813-818.

7 Hsu TH, Streem SB, Nakada SY. 9 ed Management of Upper Urinary Tract Obstruction. vol 2. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders Elsevier; 2007. In: Campbell-Walsh Urology

8 Williams B, Tareen B, Resnick M. Pathophysiology and treatment of ureteropelvic junction obstruction. Curr Urol Rep. 2007;8(2):111-117.

9 Yarlagadda SG, Perazella MA. Drug-induced crystal nephropathy: an update. Exp Opin Drug Saf. 2008;7:147-158.

10 Singh A, Sarkar SR, Gaber LW, Perazella MA. Acute Oxalate Nephropathy Associated With Orlistat, a Gastrointestinal Lipase Inhibitor. Am J Kidney Dis. 2007;49(1):153-157.

11 Stratta P, Lazzarich E, Canavese C, Bozzola C, Monga G. Ciprofloxacin Crystal Nephropathy. Am J Kidney Dis. 2007;50(2):330-335.

12 Teichman JMH. Acute Renal Colic from Ureteral Calculus. N Engl J Med. February 12, 2004;350(7):684-693.

13 Rashad SB. Schistosomiasis and the kidney. Semin Nephrol. 2003;23(1):34-41.

14 Marinkovic SP, Badlani G. Voiding and Sexual Dysfunction after Cerebrovascular Accidents. J Urol. 2001;165(2):359-370.

15 Gregory S, Diana DC. Neurogenic Bladder in Spinal Cord Injury. Phys Med Rehabil Clin N Am. 2007;18(2):255-274.

16 de Seze M, Ruffion A, Denys P, Joseph P-A, Perrouin-Verbe B. International Francophone Neuro-Urological expert study group The neurogenic bladder in multiple sclerosis: review of the literature and proposal of management guidelines. Multiple Sclerosis. August 1, 2007;13(7):915-928.

17 Sasaki KY, Yoshimura N, Chancellor MB. Implications of diabetes mellitus in urology. Urol Clin N Am. 2003;30(1):1-12.

18 Verhamme KS, Sturkenboom MC, Strickler BH, Bosch R. Drug-induced urinary retention: incidence, management and prevention. Drug Saf. 2008;31(5):373-388.

19 Arundhathi J, Kristine YL. Anatomic and Functional Changes of the Upper Urinary Tract During Pregnancy. Urol Clin North Am. 2007;34(1):1-6.

20 Kouba E, Wallen EM, Pruthi RS. Management of Ureteral Obstruction Due to Advanced Malignancy: Optimizing Therapeutic and Palliative Outcomes. J Urol. 2008;180(2):444-450.

21 van Bommel EF, Jansen I, Hendriksz TR, Aarnoudse AL. Idiopathic retroperitoneal fibrosis: prospective evaluation of incidence and clinicoradiologic presentation. Medicine Baltimore. 2009;88(4):193-201.

22 Swartz RD. Idiopathic Retroperitoneal Fibrosis: A Review of the Pathogenesis and Approaches to Treatment. Am J Kidney Dis. 2009;54(3):546-553.

23 Augusto V, Alessandra P, Domenico C, Carlo S, Carlo B. Retroperitoneal Fibrosis: Evolving Concepts. Rheum Dis Clin North Am. 2007;33(4):803-817.

24 Paravastu SCV, Ghosh J, Murray D, Farquharson FG, Serracino-Inglott F, Walker MG. A Systematic Review of Open Versus Endovascular Repair of Inflammatory Abdominal Aortic Aneurysms. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2009;38(3):291-297.

25 Shokeir AA. Renal colic: new concepts related to pathophysiology, diagnosis and treatment. Curr Opin Urol. 2002;12(4):263-269.

26 Christopher RC, Alan JW, Paul A, et al. Lower Urinary Tract Symptoms Revisited: A Broader Clinical Perspective. Eur Urol. 2008;54(3):563-569.

27 Ulleryd P, Zackrisson B, Aus G, Bergdahl S, Hugosson J, Sandberg T. Selective urological evaluation in men with febrile urinary tract infection. BJU Int. 2001;88(1):15-20.

28 Abarbanel J, Engelstein D, Lask D, Livne PM. Urinary tract infection in men younger than 45 years of age: is there a need for urologic investigation? Urology. 2003;62(1):27-29.

29 Levine J, Neitlich J, Verga M, Dalrymple N, Smith R. Ureteral calculi in patients with flank pain: correlation of plain radiography with unenhanced helical CT. Radiology. 1997;204(1):27-31.

30 Fowler K, Locken J, Duchesne J, Willamson M. US for Detecting Renal Calculi with Nonenhanced CT as a Reference Standard. Radiology. 2002;222(1):109-113.

31 Lin EP, Bhatt S, Dogra VS, Rubens DJ. Sonography of Urolithiasis and Hydronephrosis. Ultrasound Clin. 2007;2(1):1-16.

32 Jindal G, Ramchandani P. Acute Flank Pain Secondary to Urolithiasis: Radiologic Evaluation and Alternate Diagnoses. Radiol Clin North Am. 2007;45(3):395-410.

33 Katz SI, Saluja S, Brink JA, Forman HP. Radiation Dose Associated with Unenhanced CT for Suspected Renal Colic: Impact of Repetitive Studies. Am. J. Roentgenol. April 1, 2006;186(4):1120-1124.

34 Poletti P-A, Platon A, Rutschmann OT, Schmidlin FR, Iselin CE, Becker CD. Low-Dose Versus Standard-Dose CT Protocol in Patients with Clinically Suspected Renal Colic. Am J Roentgenol. April 1, 2007;188(4):927-933.

35 Vaughan JED, Marion D, Poppas DP, Felsen D. Pathophysiology of unilateral ureteral obstruction: studies from Charlottesville to New York. J Urol. 2004;172(6, Part 2):2563-2569.

36 Allen J, Vaughan JE, Gillenwater J. The effect of indomethacin on renal blood flow and uretral pressure in unilateral ureteral obstruction in a awake dogs. Invest Urol. 1978;15(4):324-327.

37 Ito K, Chen JIE, Vaughan JED, Seshan SV, Poppas DP, Felsen D. Dietary L-Arginine Supplementation Improves the Glomerular Filtration Rate and Renal Blood Flow After 24 Hours of Unilateral Ureteral Obstruction in Rats. J Urol. 2004;171(2, Part 1):926-930.

38 Chevalier R, Thornhill B, Forbes M, Kiley S. Mechanisms of renal injury and progression of renal disease in congenital obstructive nephropathy. Pediatr Nephrol. 2010;25(4):687-697.

39 Misseri R, Meldrum K. Mediators of fibrosis and apoptosis in obstructive uropathies. Curr Urol Rep. 2005;6(2):140-145.

40 Frokiaer J, Zeidel M. Urinary Tract Obstruction. Brenner and Rector’s The Kidney. vol 1. Philadelphia: W.B. Saunders Co; 2007. p. 1239-64

41 Li C, Wang W, Kwon T-H, Knepper MA, Nielsen S, Frokiaer J. Altered expression of major renal Na transporters in rats with bilateral ureteral obstruction and release of obstruction. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. November 1, 2003;285(5):F889-F901.

42 Li C, Wang W, Norregaard R, Knepper MA, Nielsen S, Frokiaer J. Altered expression of epithelial sodium channel in rats with bilateral or unilateral ureteral obstruction. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. July 1, 2007;293(1):F333-F341.

43 Kim SW, Lee J, Park JW, et al. Increased expression of atrial natriuretic peptide in the kidney of rats with bilateral ureteral obstruction. Kidney Int. 2001;59(4):1274-1282.

44 Li C, Wang W, Kwon T-H, et al. Downregulation of AQP1, -2, and -3 after ureteral obstruction is associated with a long-term urine-concentrating defect. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. July 1, 2001;281(1):F163-F171.

45 Kim SW, Cho SH, Oh BS, et al. Diminished Renal Expression of Aquaporin Water Channels in Rats with Experimental Bilateral Ureteral Obstruction. J Am Soc Nephrol. October 1, 2001;12(10):2019-2028.

46 Li C, Wang W, Knepper MA, Nielsen S, Frokiar J. Downregulation of renal aquaporins in response to unilateral ureteral obstruction. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. May 1, 2003;284(5):F1066-F1079.

47 Shi Y, Li C, Thomsen K, et al. Neonatal ureteral obstruction alters expression of renal sodium transporters and aquaporin water channels. Kidney Int. 2004;66(1):203-215.

48 Battle DC, Arruda JA, Kurtzman NA. Hyperkalemic distal renal tubular acidosis associated with obstructive uropathy. N Engl J Med. 1981;304(7):373-380.

49 Rodriguez Soriano J. Renal Tubular Acidosis: The Clinical Entity. J Am Soc Nephrol. August 1, 2002;13(8):2160-2170.

50 Wang G, Li C, Kim SW, et al. Ureter obstruction alters expression of renal acid-base transport proteins in rat kidney. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. August 1, 2008;295(2):F497-F506.

51 Khalaf IM, Shokeir AA, El-Gyoushi FI, Amr HS, Amin MM. Recoverability of renal function after treatment of adult patients with unilateral obstructive uropathy and normal contralateral kidney: A prospective study. Urology. 2004;64(4):664-668.

52 Ito K, Chen J, El Chaar M, et al. Renal damage progresses despite improvement of renal function after relief of unilateral ureteral obstruction in adult rats. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. December 1, 2004;287(6):F1283-F1293.

53 Kazutoshi O, Yuji S, Satoshi I, Yoichi A. Recovery of Renal Function after 153 Days of Complete Unilateral Ureteral Obstruction. J Urol. 1998;160(4):1422-1423.