36 Urinary tract infections

Pathogenesis

Host

Although many bacteria can readily grow in urine, and Louis Pasteur used urine as a bacterial culture medium in his early experiments, the high urea concentration and extremes of osmolality and pH inhibit growth. Other defence mechanisms include the flushing mechanism of bladder emptying, since small numbers of bacteria finding their way into the bladder are likely to be eliminated when the bladder is emptied. Moreover, the bladder mucosa, by virtue of a surface glycosaminoglycan, is intrinsically resistant to bacterial adherence. Presumably, in sufficient numbers, bacteria with strong adhesive properties can overcome this defence. Finally, when the bladder is infected, white blood cells are mobilised to the bladder surface to ingest and destroy invading bacteria. The role of humoral antibody-mediated immunity in defence against infection of the urinary tract remains unclear. Genetic susceptibility of individual patients to UTI has been reviewed (Lichtenberger and Hooton, 2008).

Investigations

Dipsticks

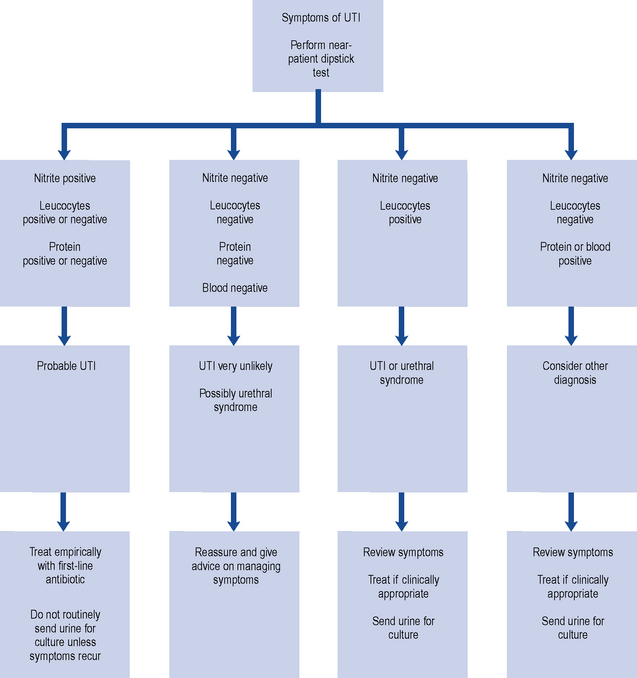

Although a negative dipstick test for leucocytes and nitrites can quite accurately predict absence of infection, their absence does not necessarily predict non-response to antibiotic treatment and further research is needed on this (Richards et al., 2005). Some experts consider that detection of nitrites in a symptomatic patient should prompt initiation of treatment (Gopal Rao and Patel, 2009). An algorithm for the use of dipstick testing in uncomplicated UTI in adult women is set out in Fig. 36.1.

Treatment

Although many, and perhaps most, cases clear spontaneously given time, symptomatic UTI usually merits antibiotic treatment to eradicate both symptoms and pathogen. Asymptomatic bacteriuria may or may not need treatment depending upon the circumstances of the individual case. Bacteriuria in children and in pregnant women requires treatment, as does bacteriuria present when surgical manipulation of the urinary tract is to be undertaken, because of the potential complications. On the other hand, in non-pregnant, asymptomatic bacteriuric adults without any obstructive lesion, screening and treatment are probably unwarranted in most circumstances (Nicolle et al., 2005). Unnecessary treatment will lead to selection of resistant organisms and puts patients at risk of adverse drug effects including bowel infection with Clostridium difficile, which has been particularly associated with the use of cephalosporins and quinolones. A number of common management problems are summarised in Table 36.1.

Table 36.1 Common management problems with urinary tract infections (UTI)

| Problem | Comments |

|---|---|

| Asymptomatic infection | Asymptomatic bacteriuria should be treated where there is a risk of serious consequences (e.g. in childhood), where there is renal scarring, and in pregnancy. Otherwise, treatment is not usually required |

| Catheter in situ, patient unwell | Systemic symptoms may result from catheter-associated UTI, and should respond to antibiotics although the catheter is likely to remain colonised. Local symptoms such as urgency are more likely to reflect urethral irritation than infection |

| Catheter in situ, urine cloudy or smelly | Unless the patient is systemically unwell, antibiotics are unlikely to achieve much and may give rise to resistance. Interventions of uncertain benefit include bladder wash-outs or a change of catheter |

| Penicillin allergy | Clarify ‘allergy’: vomiting or diarrhoea are not allergic phenomena and do not contraindicate penicillins. Penicillin-induced rash is a contraindication to amoxicillin, but cephalosporins are likely to be tolerated. Penicillin-induced anaphylaxis suggests that all β-lactams should be avoided |

| Symptoms of UTI but no bacteriuria | Exclude urethritis, candidosis, etc. Otherwise likely to be urethral syndrome, which usually responds to conventional antibiotics |

| Bacteriuria but no pyuria | May suggest contamination. However, pyuria is not invariable in UTI and may be absent particularly in pyelonephritis, pregnancy, neonates, the elderly, and Proteus infections |

| Pyuria but no bacteriuria | Usually, the patient has started antibiotics before taking the specimen. Rarely, a feature of unusual infections (e.g. anaerobes, tuberculosis, etc.) |

| Urine grows Candida | Usually reflects perineal candidosis and contamination. True candiduria is rare, and may reflect renal candidosis or systemic infection with candidaemia |

| Urine grows two or more organisms | Mixed UTI is unusual – mixed cultures are likely to reflect perineal contamination. A repeat should be sent unless this is impractical (e.g. frail elderly patients), in which case best-guess treatment should be instituted if clinically indicated |

| Symptoms recur | May represent relapse or reinfection. A repeat urine culture should be performed shortly after treatment |

Antimicrobial chemotherapy

Antibiotic resistance

ESBL-producing bacteria are clinically important as they produce enzymes that destroy almost all commonly used β-lactams except the carbapenem class, rendering most penicillins and cephalosporins largely useless in clinical practice. Some ESBL enzymes can be inhibited by clavulanic acid, and combinations of an agent containing it, for example, co-amoxiclav, with other oral broad-spectrum β-lactams, for example, cefixime or cefpodoxime, have been used to treat UTIs caused by ESBL-producing E. coli (Livermore et al., 2008). These combinations are unlicensed and their effectiveness is variable.

In addition, many ESBL-producing bacteria are multiresistant to non-β-lactam antibiotics too, such as quinolones, aminoglycosides and trimethoprim, narrowing treatment options. ESBL-E. coli is often pathogenic and a high proportion of infections result in bacteraemia with resultant mortality (Tumbarello et al., 2007). Some strains cause outbreaks both in hospitals and in the community. Empirical treatment strategies may need to be reviewed in settings where ESBL-producing strains are prevalent, and it may be considered appropriate to use a carbapenem in seriously ill patients until an infection has been proved not to involve an ESBL producer.

Recently, even more resistant strains have emerged in India and Pakistan, with subsequent transfer to the UK, that carry a gene for a novel New Delhi metallo-β-lactamase-1 that also confers resistance to carbapenems. This blaNDM-1 gene was mostly found among E. coli and Klebsiella, which were highly resistant to all antibiotics except to colistin and tigecycline, which is not effective for UTI as it is chemically unstable in the urinary tract (Kumarasamy et al., 2010).

Uncomplicated lower UTI

The problem with empirical treatment is that over 10% of the healthy adult female population would receive an antibiotic each year. The use of antibiotics to this extent in the population has implications for antibiotic resistance, a major focus of public health policy worldwide. This highlights the tension between maximising the benefit for individuals and minimising antibiotic resistance at a population level. Strategies have included diagnostic algorithms to predict more precisely who has a UTI, as well as issuing delayed prescriptions (Mangin, 2010).

Therapeutic decisions should be based on accurate, up-to-date antimicrobial susceptibility patterns. Data have been published from a European multicentre survey that examined the prevalence and antimicrobial susceptibility of community-acquired pathogens causing uncomplicated UTI in women (Kahlmeter, 2003). Among almost 2500 E. coli isolates, the resistance rates were 30% for amoxicillin, 15% for trimethoprim, 3.4% for co-amoxiclav, 2.3% for ciprofloxacin, 2.1% for cefadroxil and 1.2% for nitrofurantoin. These figures are lower than most routine laboratory data would suggest, but it should be remembered that the experience of diagnostic laboratories is likely to be biased by the overrepresentation of specimens from patients in whom empirical treatment has already failed. It is important to be aware of local variations in sensitivity pattern and to balance the risk of therapeutic failure against the cost of therapy.

Adults

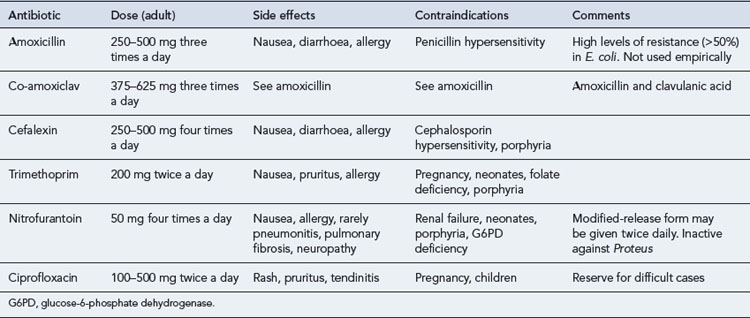

The preference for best-guess therapy would seem to be a choice between trimethoprim, an oral cephalosporin such as cefalexin, co-amoxiclav or nitrofurantoin, with the proviso that therapy can be refined once sensitivities are available. The quinolones are best reserved for treatment failures and more difficult infections, since overuse of these important agents is likely to lead to an increase in resistance, as has been seen in countries such as Spain and Portugal. These recommendations are summarised in Table 36.2.

Other drugs that have been used for the treatment of UTI include co-trimoxazole, pivmecillinam, fosfomycin and earlier quinolones such as nalidixic acid. Co-trimoxazole is now recognised as a cause of bone marrow suppression and other haematological side effects, and in the UK, its use is greatly restricted. Further, despite superior activity in vitro, there is no convincing evidence that it is clinically superior to trimethoprim alone in the treatment of UTI caused by strains susceptible to both. Pivmecillinam is an oral pro-drug that is metabolised to mecillinam, a β-lactam agent with a particularly high affinity for Gram-negative penicillin-binding protein 2 and a low affinity for commonly encountered β-lactamases, and which therefore has theoretical advantages in the treatment of UTI. Pivmecillinam has been extensively used for cystitis in Scandinavian countries, where it does not seem to have led to the development of resistance, and for this reason, there have been calls for wider recognition of its usefulness, particularly for UTI caused by ESBL-producing strains. Fosfomycin is a broad-spectrum antibiotic with pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic properties that favour its use for treatment of cystitis with a single oral dose (Falagas et al., 2010). Finally, older quinolones such as nalidixic acid and cinoxacin were once widely used, but generally these agents have given ground to the more active fluorinated quinolones.

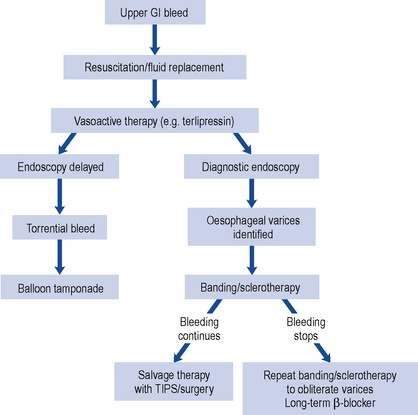

Acute pyelonephritis

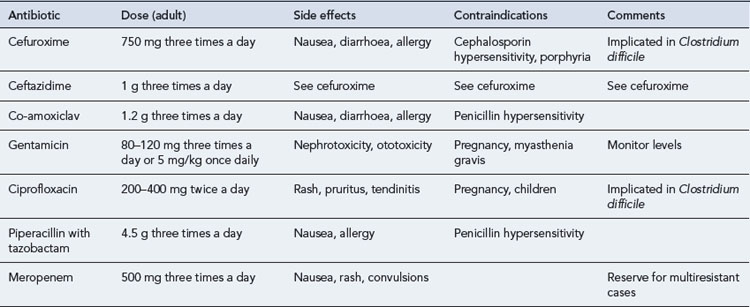

Patients with pyelonephritis may be severely ill and, if so, will require admission to hospital and initial treatment with a parenteral antibiotic. Suitable agents with good activity against E. coli and other Gram-negative bacilli include cephalosporins such as cefuroxime and ceftazidime, some penicillins such as co-amoxiclav, quinolones, and aminoglycosides such as gentamicin (Table 36.3). A first-choice agent would be parenteral cefuroxime, gentamicin or ciprofloxacin. When the patient is improving, the route of administration may be switched to oral therapy, typically using a quinolone. Conventionally, treatment is continued for 10–14 days.

Patients who are less severely ill at the outset may be treated with an oral antibiotic, and possibly with a shorter course of treatment. The safety of this approach has been demonstrated in a study of adult women with acute uncomplicated pyelonephritis (Talan et al., 2000). Among 113 patients treated with oral ciprofloxacin 500 mg twice daily for 7 days (± an initial intravenous dose), the cure rate was 96%.

Bacteriuria of pregnancy

The prevalence of asymptomatic bacteriuria of pregnancy is about 5%, and about a third of these women proceed to develop acute pyelonephritis, with its attendant consequences for the health of both mother and pregnancy. Further, there is evidence that asymptomatic bacteriuria is associated with low birth weight, prematurity, hypertension and pre-eclampsia. For these reasons, it is recommended that screening be carried out, preferably by culture of a properly taken MSU, which should be repeated if positive for confirmation (National Collaborating Centre for Women’s and Children’s Health, 2003).

Prevention and prophylaxis

Cranberry juice

Cranberry juice (Vaccinium macrocarpon) has long been thought to be beneficial in preventing UTI, and this has been studied in a number of clinical trials. Cranberry is thought to inhibit adhesion of bacteria to urinary tract cells on the surface of the bladder. In sexually active women, a daily intake of 750 mL cranberry juice was associated with a 40% reduction in the risk of symptomatic UTI in a double-blinded 12-month trial. Many studies have been criticised for methodological flaws, and currently there is only limited evidence that cranberry juice is effective at preventing recurrent UTI (McMurdo et al., 2009). There have been no randomised controlled trials of the use of cranberry products (juice, tablets or capsules) in the treatment of established infection, or comparing it with established therapies such as antibiotics for preventing infection.

Children

In children, recurrence of UTI is common and the complications potentially hazardous, so many clinicians recommend antimicrobial prophylaxis following documented infection. The evidence in favour of this practice is not strong (Le Saux et al., 2000), and although it has been shown to reduce the incidence of bacteriuria, there is no good-quality evidence that prophylactic antibiotics are effective in preventing further symptomatic UTIs and they have not been shown to reduce the incidence of renal scarring complications, which are the most important outcomes for the patient (Mori et al., 2009). Further, important variables remain to be clarified, such as when to begin prophylaxis, which agent to use and when to stop. Recent guidelines have abandoned the time-honoured recommendation for routine antibiotic prophylaxis following a first infection, although it may be considered when there is recurrent UTI (NICE, 2007).

Answer

In post-menopausal women, there have been trials assessing the merits of topical oestrogen creams. Topical intravaginal oestriol cream has significant benefits in reducing the number of UTIs in those suffering recurrent infections. In a placebo-controlled trial, the rate of UTI was 12-fold less in the group receiving active oestrogen cream. This effect is not seen with oral oestrogens (Perrotta et al., 2008).

Falagas M.E., Vouloumanou E.K., Togias A.G., et al. Fosfomycin versus other antibiotics for the treatment of cystitis: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J. Antimicrob. Chemother.. 2010;65:1862-1877.

Gopal Rao G., Patel M. Urinary tract infection in hospitalized elderly patients in the United Kingdom: the importance of making an accurate diagnosis in the post broad-spectrum antibiotic era. J. Antimicrob. Chemother.. 2009;63:5-6.

Kahlmeter G. An international survey of the antimicrobial susceptibility of pathogens from uncomplicated urinary tract infections: the ECO•SENS Project. J. Antimicrob. Chemother.. 2003;51:59-76.

Kumarasamy K.K., Toleman M.A., Walsh T.R., et al. Emergence of a new antibiotic resistance mechanism in India, Pakistan, and the UK: a molecular, biological, and epidemiological study. Lancet Infect. Dis.. 2010;10:597-602.

Le Saux N., Pham B., Moher D. Evaluating the benefits of antimicrobial prophylaxis to prevent urinary tract infections in children: a systematic review. Can. Med. Assoc. J.. 2000;163:523-529.

Lichtenberger P., Hooton T.M. Complicated urinary tract infections. Curr. Infect. Dis. Rep.. 2008;10:499-504.

Livermore D.M., Hope R., Mushtaq S., et al. Orthodox and unorthodox clavulanate combinations against extended-spectrum β-lactamase-producers. Clin. Microbiol. Infect.. 2008;14(Suppl. 1):198-202.

Mangin D. Urinary tract infection in primary care. Br. Med. J.. 2010;340:373-374.

McMurdo M.E.T., Argo I., Phillips G., et al. Cranberry or trimethoprim for the prevention of recurrent urinary tract infections? A randomized controlled trial in older women. J. Antimicrob. Chemother.. 2009;63:389-395.

Mori R., Fitzgerald A., Williams C., et al. Antibiotic prophylaxis for children at risk of developing a urinary tract infection: a systematic review. Acta Paediatr.. 2009;98:1781-1786.

National Collaborating Centre for Women’s and Children’s Health. Antenatal Care: Routine Care for the Healthy Pregnant Woman. London: Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists Press. 2003:79-81.

National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. Urinary Tract Infection in Children: Diagnosis, Treatment and Long-Term Management. London: NICE; 2007. Available at http://www.nice.org.uk/nicemedia/pdf/CG54fullguideline.pdf (1 October 2010, date last accessed)

Nicolle L.E., Bradley S., Colgan R., et al. Infectious Diseases Society of America guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of asymptomatic bacteriuria in adults. Clin. Infect. Dis.. 2005;40:643-654.

Perrotta C., Aznar M., Mejia R., et al. Oestrogens for preventing recurrent urinary tract infection in postmenopausal women. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2008. Issue 2 Art No. CD 005131 doi:10.1002/14651858.CD005131.pub2

Richards D., Toop L., Chambers S., et al. Response to antibiotics of women with symptoms of urinary tract infection but negative dipstick urine test results: double blind randomised controlled trial. Br. Med. J.. 2005;331:143-146.

Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network. Management of Suspected Bacterial Urinary Tract Infection in Adults. Edinburgh: SIGN; 2006. Available at http://www.sign.ac.uk/guidelines/fulltext/88/index.html (1 October 2010, date last accessed)

Talan D.A., Stamm W.E., Hooton T.M. Comparison of ciprofloxacin (7 days) and trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (14 days) for acute uncomplicated pyelonephritis in women: a randomized trial. J. Am. Med. Assoc.. 2000;283:1583-1590.

Tumbarello M., Sanguinetti M., Montuori E., et al. Predictors of mortality in patients with bloodstream infections caused by extended-spectrum β-lactamase-producing Enterobacteriaceae: importance of inadequate initial antimicrobial treatment. J. Antimicrob. Chemother.. 2007;51:1987-1994.

Anonymous. Cranberry and urinary tract infection. Drug Ther. Bull.. 2005;43:17-19.

Hooton T.M. Nosocomial urinary tract infections. In: Mandell G.L., Bennett J.E., Dolin R., editors. Principles and Practice of Infectious Diseases. London: Elsevier; 2010:3725-3737.

Pallett A., Hand K. Complicated urinary tract infections: practical solutions for the treatment of multiresistant Gram-negative bacteria. J. Antimicrob. Chemother.. 2010;65(Suppl. 3):iii25-iii33.

Sobel J.D., Kaye D. Urinary tract infections. In: Mandell G.L., Bennett J.E., Dolin R., editors. Principles and Practice of Infectious Diseases. London: Elsevier; 2010:957-985.

Stamm W.E. Urinary tract infections and pyelonephritis. In: Kasper, D.L., Braunwald E., Fauci A.S., et al, editors. Harrison’s Principles of Internal Medicine. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2005:1715-1721.