30 Schizophrenia

Classification

Two systems for the classification of schizophrenia are widely used: the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th edition (DSM IV; American Psychiatric Association, 1994) and the International Classification of Diseases, 10th edition (ICD 10; World Health Organization, 1992).

Symptoms and diagnosis

Acute psychotic illness

These symptoms are commonly called positive symptoms.

Factors affecting diagnosis and prognosis

Causes of schizophrenia

Although the cause of schizophrenia remains unknown, there are many theories and models.

Drug treatment

Rationale for use of drugs

It is now accepted that antipsychotic drugs can control or modify symptoms such as hallucinations and delusions that are evident in the acute episode of illness. Except for clozapine and the other atypicals, there is little evidence for antipsychotic drugs being of value in the treatment of the negative symptoms, although the matter remains controversial (Chakos et al., 2001). Antipsychotic drugs increase the length of time between breakdowns and shorten the length of the acute episode in most patients.

Drug selection and dose

Side effects

Concerns about the EPSEs and toxicity of typical antipsychotic drugs led to calls over the past 10 years for the ‘atypicals’ to be prescribed more widely. This approach was supported in national guidance which advocated that atypical antipsychotic drugs should be used for the treatment of a first illness. However, increasing concern about the side effects of the atypical antipsychotic drugs, which includes weight gain, diabetes and sexual dysfunction, has led many clinicians to question the benefits of the newer and more expensive atypical antipsychotics. In more recent guidance (National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence, 2009), it has been advocated that:

Information on the advantages and disadvantages of the various antipsychotic drugs can be found in Table 30.1.

Table 30.1 Neuroleptics/antipsychotics and their commonly associated attributes and problems

| Drug group | Drug | Comment |

|---|---|---|

| Butyrophenones | Haloperidol | Regarded as the gold standard reference antipsychotic |

| Extrapyramidal side effects of parkinsonian rigidity, dystonia, akathisia | ||

| Tardive dyskinesia with long-term use | ||

| Drug most associated with neuroleptic malignant syndrome | ||

| Sedation common | ||

| Hormonal effects common | ||

| Wide range of formulations including long-acting injection | ||

| Benperidol | As haloperidol | |

| Claimed to reduce sexual drive, although little evidence to support the claim | ||

| Phenothiazines | ||

| Piperidine | Pericyazine | Marked anticholinergic side effects of dry mouth, blurred vision and constipation |

| Postural hypotension and falls in the elderly | ||

| Lower incidence of extrapyramidal side effects | ||

| Pipotiazine | As pericyazine but only available as depot formulation | |

| Aliphatic | Chlorpromazine | As haloperidol but in addition postural hypotension, low body temperature, rashes and photosensitivity |

| Increased sedative effects | ||

| Promazine | As chlorpromazine but low potency | |

| Considered by some to have weak antipsychotic effect | ||

| Levomepromazine | Very sedative and postural hypotension common | |

| (methotrimeprazine) | Mostly used in terminal illness | |

| Piperazine | Trifluoperazine | As chlorpromazine but greater incidence of extrapyramidal side effects and lower incidence of anticholinergic effects |

| Tardive dyskinesia with long-term use | ||

| Some antiemetic properties | ||

| Fluphenazine | As trifluoperazine but also available as depot formulation | |

| Perphenazine | As trifluoperazine | |

| Thioxanthines | Flupentixol | Similar to fluphenazine but also available as depot formulation |

| Zuclopenthixol | Similar to chlorpromazine but also available as depot formulation | |

| Diphenylbutylpiperidines | Pimozide | As haloperidol but concerns about cardiac effects at high dose limits use |

| Benzamides | Sulpiride | Lower incidence of extrapyramidal effects |

| Few anticholinergic effects | ||

| Useful adjunct to clozapine in refractory illness | ||

| Amisulpride | As sulpiride | |

| Dibenoxazepine tricyclics | Clozapine | Drug of choice for treatment-resistant schizophrenia |

| Low incidence of extrapyramidal side effects or tardive dyskinesia | ||

| Neutropenia in 1–2% of cases | ||

| Enhanced efficacy against both positive and negative symptoms | ||

| Sedation, dribbling, drooling, weight gain and diabetes | ||

| Thienobenzodiazepines | Olanzapine | Sedation, weight gain and diabetes |

| Low incidence of extrapyramidal side effects and low impact on prolactin | ||

| Quetiapine | Low incidence of extrapyramidal side effects and low impact on prolactin | |

| Zotepine | Similar to olanzapine but higher rate of prolactin elevation and higher rate of drug-induced seizures | |

| Serotonin–dopamine antagonists | Risperidone | Extrapyramidal side effects at higher doses. High rate of prolactin elevation |

| Paliperidone | As risperidone | |

| Ziprasidone | As risperidone | |

| Sertindole | Available on named patient basis only due to risk of sudden cardiac events | |

| Partial dopamine agonist | Aripiprazole | Low level of side effects but light-headedness and blurred vision common |

Clozapine and refractory illness

Clozapine was developed as an antipsychotic drug during the 1960s. Unfortunately, use is associated with a 1–2% incidence of neutropenia and this initially resulted in the withdrawal of the drug from clinical practice. However, it was noted even at an early stage in the drug’s history that it was free of the extrapyramidal side frequently seen with the other antipsychotic drugs. In the 1980s, clozapine was demonstrated to have a greater efficacy than other antipsychotics (Kane et al., 1988; Lieberman et al., 1994) and was subsequently reintroduced into clinical practice but with routine monitoring of blood mandatory.

Clozapine is now established as the drug of choice in treatment-resistant schizophrenia but it is not without problems (Tuunainen et al., 2000). In addition to neutropenia, it is associated with a greater risk of seizures, particularly if doses are above 600 mg daily. Some guidelines recommend the co-prescribing of sodium valproate to reduce this risk. In addition, use is associated with excessive drooling, hypotension and sedation during the early stages of treatment, requiring slow dose increases initially.

A regimen of gradual dose increases starting at 12.5 mg twice daily aiming to reach 300 mg in 2–3 weeks is normally recommended. However, this rate of dose increase is frequently too rapid, with tachycardia being a particular problem. In such cases, it is usual to slow down the rate of dose increase to a half or a quarter of that recommended. Although tachycardia is a common problem with clozapine initiation, if use is associated with fever, chest pain or hypotension this may indicate a high risk of myocarditis and the drug should be stopped (Committee on Safety of Medicines, 2002).

Polypharmacy

Neuroleptic equivalence

Although antipsychotic drugs vary in potency, studies on relative dopamine receptor binding have led to the concept of chlorpromazine equivalents as a useful method of transferring dosage from one product to another. Concern has been expressed about the variation between sources for such values, in particular about the quoted chlorpromazine equivalents of the butyrophenones and the conversion of depot doses to oral doses (Table 30.2). Likewise, there is no agreement on the equivalent doses of the atypicals.

Table 30.2 Equivalence of typical antipsychotic drugs to 100 mg chlorpromazine (from Foster, 1989)

| Drug | Usual dose (mg) equivalent of to 100 mg chlorpromazine | Variations in quoted dosage (mg) equivalent to 100 mg of chlorpromazine |

|---|---|---|

| Oral antipsychotics | ||

| Promazine | 200 | 100–250 |

| Thioridazine | 100 | 50–120 |

| Trifluoperazine | 5 | 3.5–7.5 |

| Haloperidol | 2 | 1.5–5 |

| Sulpiride | 200 | – |

| Depot antipsychotics administered every 2 weeks (all administered as the decanoate) | ||

| Zuclopenthixol | 200 | 80–200 |

| Flupentixol | 40 | 16–40 |

| Fluphenazine | 25 | 10–25 |

| Haloperidol | 20 | – |

Augmentation strategies and polytherapy

In addition to the above, complex prescriptions can arise when treatment with clozapine is perceived to be inadequate or doses are limited due to side effects. The theory behind the addition of a further drug can be either that the plasma concentration of the clozapine will be enhanced by the addition of another drug, or the second drug will enhance a particular receptor blockade which may be considered necessary in a specific patient (Cipriani et al., 2009; Paton et al., 2007). The augmentation strategy with the best evidence to support its use is the addition of sulpiride or amisulpride to clozapine. Other strategies include the addition of risperidone, lamotrigine or Ω3 fatty acids. However, many of the trials that support these augmentation strategies are small scale and a meta-analysis concluded that no single strategy was superior to another (Paton et al., 2007).

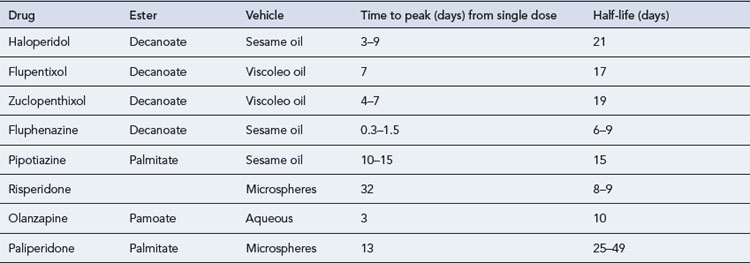

Long-acting formulations of antipsychotic drugs

Although the ideal long-acting antipsychotic formulation should release the drug at a constant rate so that plasma level fluctuations are kept to a minimum, all the available products produce significant variations (Table 30.3). This can result in increased side effects at the time of peak plasma concentrations, usually after 5–7 days, for oil-based depots and increased patient irritability towards the end of the period, as plasma concentrations decline. For many patients though, oil-based long-acting formulations result in a very slow decline in drug availability after a period of chronic administration (Altamura et al., 2003). When transferring a patient from depot formulations to oral administration, it may be many months before the effect of the depot finally wears off.

Adverse effects and antipsychotic medicines

There are a large number of adverse effects associated with antipsychotic medicines. Some of these effects, such as sedation, antilibido effects and weight gain may be considered to be of value with particular patients, but the susceptibility to such adverse effects is often a major factor in determining drug choice. Prescribing guidelines are available (Bazire, 2009; Taylor et al., 2009) which provide details of the relative likelihood of side effects with the various antipsychotic drugs. The major side effects are set out below.

Neuroleptic malignant syndrome (NMS)

Answers

Answers

Answers

Altamura A., Sassella F., Santini A., et al. Intramuscular preparations of antipsychotics uses and relevance in clinical practice. Drugs. 2003;63:493-512.

American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, fourth ed. Washington: American Psychiatric Association; 1994.

Bazire S. Psychotropic Drug Directory: The Professionals’ Pocket Handbook and Aide Memoire. Salisbury: Fivepin Ltd; 2009.

Chakos M., Lieberman J.A., Hoffman E., et al. Effectiveness of second-generation antipsychotics in patients with treatment-resistant schizophrenia: a review and meta-analysis of randomized trials. Am. J. Psychiatry. 2001;158:518-526.

Cipriani A., Boso M., Barbui C. Clozapine combined with different antipsychotic drugs for treatment resistant schizophrenia. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev.. (3):2009. Art. No. CD006324 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD006324.pub2. Available at: http://www2.cochrane.org/reviews/en/ab006324.html

Committee on Safety of Medicines. Clozapine and cardiac safety: updated advice for prescribers. Curr. Probl. Pharmacovigil.. 2002;28:8.

Kane J., Honigfield G., Singer J., et al. Clozapine for the treatment-resistant schizophrenic; a double blind comparison with chlorpromazine (clozaril collaborative study). Arch. Gen. Psychiatry. 1988;45:789-796.

Lieberman J.A., Safferman A.Z., Pollack S., et al. Clinical effects of clozapine in chronic schizophrenia: response to treatment and predictors of outcome. Am. J. Psychiatry. 1994;15:1744-1752.

National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. Schizophrenia: Core Interventions in the Treatment and Management of Schizophrenia in Adults in Primary and Secondary Care. Clinical guideline 82 update http://www.nice.org.uk/nicemedia/live/11786/43608/43608.pdf, 2009.

Paton C., Whittington C., Barnes T. Augmentation with a second antipsychotic in patients with schizophrenia who partially respond to clozapine: a meta-analysis. J. Clin. Psychopharmacol.. 2007;27:198-204.

Royal College of Psychiatrists. Consensus Statement on High-Dose Antipsychotic Medication. London: RCP; 2006. CR138

Taylor D., Paton C., Kapur S. The Maudsley Prescribing Guidelines, 10th ed. London: Informa Healthcare; 2009.

Tuunainen A., Wahlbeck K., Gilbody S. Newer atypical antipsychotic medication versus clozapine for schizophrenia. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev.. (1):2000. Art No. CD000966. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD000966

World Health Organization. International Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, 10th ed. Geneva: World Health Organization; 1992. (ICD 10)

Barbui C., Signoretti A., Mule S., et al. Does the addition of a second antipsychotic drug improve clozapine treatment? Schizophr. Bull.. 2009;35:458-468.

Bobo W.V., Stovall J.A., Knostman M., et al. Converting from brand-name to generic clozapine: a review of effectiveness and tolerability data. Am. J. Health Syst. Pharm.. 2010;67:27-37.

Gao K., Gajwani P., Elhaj O., Calabrese J.R. Typical and atypical antipsychotics in bipolar depression. J. Clin. Psychiatry. 2005;66:1376-1385.

Lang U., Willbring M., von Golitschek R., et al. Clozapine-induced myocarditis after long-term treatment: case presentation and clinical perspectives. J. Psychopharmacol.. 2008;22:576-580.

Leucht S., Komossa K., Rummel-Kluge C., et al. A meta-analysis of head-to-head comparisons of second-generation antipsychotics in the treatment of schizophrenia. Am. J. Psychiatry. 2009;166:152-163.

Lieberman J.A., Stroup T.S., McEvoy J.P., for the Clinical Antipsychotic Trials of Intervention Effectiveness (CATIE) Investigators. Effectiveness of antipsychotic drugs in patients with chronic schizophrenia. N. Engl. J. Med.. 2005;353:1209-1223.

National Collaborating Centre for Mental Health. Schizophrenia: The NICE Guideline on Core Interventions in the Treatment and Management of Schizophrenia in Adults in Primary and Secondary Care. London: British Psychological Society; 2010.