CHAPTER 9 Urinary Complaints

URINARY TRACT INFECTION

Urinary tract infection (UTI) refers to the presence of microbes anywhere in the urinary tract, ranging from the distal urethra to the kidney. UTI in the kidney is called pyelonephritis; in the bladder, cystitis; and in the urethra, urethritis. Infection is usually caused by bacteria, particularly E. coli, which accounts for 85% to 90% of all UTIs, but also may be caused by other bacteria, viral, and fungal infection. Klebsiella, Proteus, and Pseudomonas are commonly associated with UTI, particularly in recurrent cases. Urine itself is normally sterile, but the moist environment of the periurethral area, the proximity of the urethral orifice to the rectum, and the short length of the urethra provide a conducive environment for the growth and ascension of potential uropathogenic microorganisms into the urinary system. The presence of bacteria in the urine is called bacteriuria. In nonpregnant women bacteriuria in the absence of symptoms is not considered an indication for treatment; however, during pregnancy, bacteriuria is associated with increased risk of pyelonephritis as well as prematurity and possibly other complications; therefore, UTI in pregnancy requires special consideration. 1 2 3

UTI INCIDENCE AND ETIOLOGY

It is estimated that several hundred million women suffer from UTI annually, with costs to health care providers amounting to over $6 billion annually worldwide, a figure that may even be an underestimate.4 Additional costs to society of UTI are tremendous in terms of the personal suffering of millions of women annually, lost work days, and childcare costs. Over 56% of women will experience a UTI in their lifetimes, and among those experiencing uncomplicated acute UTI, as many as 20% will have a recurrence within 6 months. Overall UTI recurrence rate is between 27% and 48%.4 Even with treatment, symptoms typically last for an average of 6 days, with nearly 2.5 days of limited activity. The rates of UTI are slightly higher in young, sexually active women because of mechanical factors affecting the urethra and the presence of uropathogenic organisms. UTI rates increase during pregnancy and with age, the former because of mechanical pressure of the growing uterus on the ureters and bladder preventing complete voiding, and the latter because of declining estrogen levels, declining mucin (a surface coating of the bladder epithelium that prevents bacterial adhesion), inability to void completely, incontinence, inadequate nutrition, and the occurrence of other disease and excessive catheter use as a result of medical procedures.

RISK FACTORS FOR URINARY TRACT INFECTION

A number of common factors appear to increase the risk of developing a UTI. As mentioned, sexual activity is associated with a higher incidence of symptomatic UTI; however, risk only seems to be increased in the presence of uropathogenic microorganisms, either from a woman’s own reservoir of bowel microbes, or passed from a sexual partner. Urinating after sexual activity decreases the rates of infection. Evidence suggests that host genetic factors influence susceptibility to UTI. A maternal history of UTI is more often found among women who have experienced recurrent UTIs than among controls. Susceptible patients may have a genetically increased number of receptors on uroepithelial cells to which bacteria may adhere. Additionally, nonsecretors of specific blood group antigens, which are glycoproteins, are at increased risk of recurrent UTI. Mutations in host genes integral to the immune response (interferon receptors and others) also may affect susceptibility to UTI.3 The use of oral contraceptives doubles the risk of UTI compared with no birth control, and the use of diaphragms and spermicides doubles the rate of UTI compared with OCs. Sexually transmitted infections and vaginitis can cause urethritis. Dehydration can increase bacterial growth leading to UTI. A history of antibiotic use is common in women with a UTI; a possible mechanism that has been suggested is disruption of the vaginal flora and consequently overgrowth of pathogenic organisms. An interesting correlation exists between recurrent UTI and exposure to cold. A case-controlled study demonstrated a higher rate of UTI in women who reported cold hands, feet, or buttocks in women with UTI than controls. In a nonrandomized crossover study, cooling the feet of 29 healthy women with a history of recurrent UTI led to the development of UTI in five participants, compared with no UTI development in the control group.1

SYMPTOMS

Pyelonephritis commonly has a gradual onset, although it can seem sudden if preceded by lower UTI, and is associated with not only urinary symptoms, but generalized symptoms such as fever, chills, nausea, malaise, and mild to extremely severe lower to middle back discomfort. Patients with pyelonephritis may appear quite ill. It is critical to differentiate between the symptoms of cystitis and pyelonephritis, as the latter requires more aggressive treatment and carries greater risks, particularly during pregnancy (Box 9-1). Cystitis may resolve spontaneously; however, effective treatment lessens the duration of symptoms and reduces the incidence of progression to upper UTI. Pyelonephritis is associated with substantial morbidity. Complications include acute papillary necrosis with possible development of urethral obstruction, septic shock, and perinephric abscess. Chronic pyelonephritis may lead to scarring with diminished renal function.

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

Primary differential diagnoses include urethritis, cystitis, and pyelonephritis.2 In women with recurring infection, it is important to differentiate between relapse and reinfection. Additional considerations for acute or chronic UTI include:5

CONVENTIONAL TREATMENT APPROACHES

Oral antibiotics effective against gram-negative aerobic coliform bacteria, particularly E. coli, is the principal treatment in patients with UTI. A 3-day course is typical in patients with an uncomplicated lower UTI or simple cystitis with symptoms for less than 48 hours. A bladder analgesic may be given if the patient has intense dysuria. Increased fluid intake is often recommended to promote dilute urine flow. Pregnant, otherwise healthy women with no evidence of an upper UTI may be treated with a 7- to 10-day course of a cephalosporin, such as cephalexin, even in the absence of upper urinary tract signs. Pregnant women are typically treated for all episodes of bacteriuria, even in the absence of symptoms. Upper UTI requires antibiotic treatment and may require IV therapy and hospitalization. In most cases, pyelonephritis responds to antibiotic treatment in 48 to 72 hours.5 Therapeutic approaches to treatment and prevention of urogenital infections have remained essentially unchanged for many years. Antibiotics and antifungals remain the mainstay of therapy. Several antibiotic therapies have become less effective because of antibiotic resistance, and the use of antibiotics in pregnancy often leads to vaginal yeast infection requiring treatment.6

Lifestyle changes may be recommended, such as teaching the client to void at the first urge to urinate, void after intercourse, drink adequate fluids, and avoid contraceptives associated with high UTI risk. Estrogen cream may be recommended for older women.1,2 Other risk factors may include use of menstrual pads (i.e., rather than tampons), wiping the anogenital region from back to front after a bowel movement (front to back is the proper motion), wearing nonabsorbent underpants or pantyhose, and bubble baths with irritating soaps; however, none of these factors have been found to be significant in clinical trials.1 Increasingly, conventional practitioners are recommending the use of cranberry juice and vitamin C for UTI treatment. These are discussed under Botanical Protocol.

THE BOTANICAL PRACTITIONER’S PERSPECTIVE

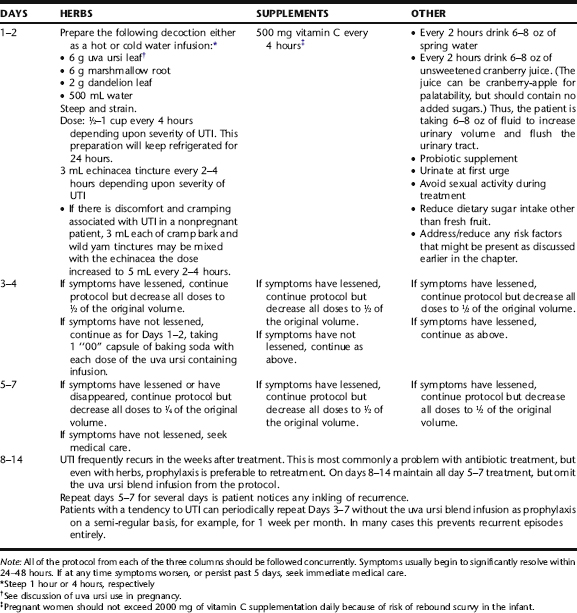

Botanical medicine provides an excellent alternative to antibiotic use for reducing the duration and symptoms of lower UTI, preventing progression to upper UTI, and preventing recurrence. Lower UTI in nonpregnant women is often easily treated with simple protocol. Because of the risks associated with untreated pyelonephritis, it is recommended that patients with upper UTI be referred for medical care, and that botanical interventions be used in the context of complementary care. Care of pregnant women requires specific expertise in midwifery or obstetrics, as well as knowledge of herbs that are contraindicated in pregnancy, and must be done in consultation with an obstetric care provider. This section provides guidelines for the treatment of uncomplicated cystitis (Table 9-1).

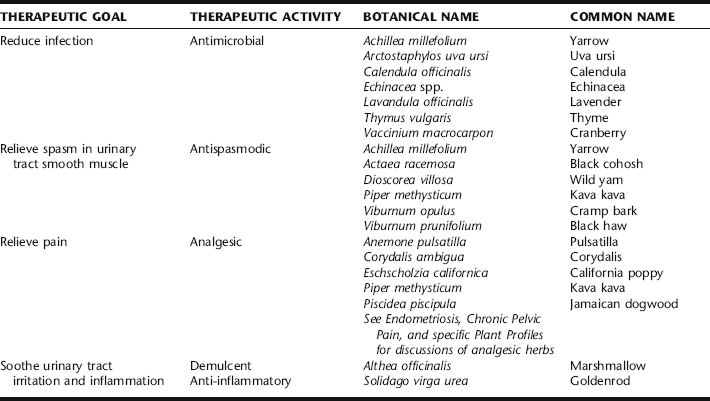

Botanical treatment of lower UTI incorporates the use of urinary antiseptic and antimicrobial herbs with demulcent herbs (Table 9-2). Additionally, a diuretic may be included to assist the body in its attempt to increase the delivery of fluids through the bladder. Herbs for cramping and aching may be included if needed. Herbs are used in the context of an overall protocol to increase fluids and diuresis, and to relieve offending lifestyle causes (e.g., chronic vulvovaginitis, overgrowth of uropathogenic bowel flora, or use of birth control methods or sexual habits that may contribute to the problem). Rarely UTI can lead to vaginal bleeding, sometimes quite copious. If this occurs seek medical care.

Calendula, Thyme, and Lavender

Calendula is typically used as a topical anti-inflammatory rinse with mild antimicrobial activity, either in the form of an infusion or diluted tincture, 1 tbs/125 mL water. Thyme and lavender are used topically for their antimicrobial activity and mild anti-inflammatory activity. in the form of peri-rinses for the treatment of urethritis associated with vulvo-vaginitis, and also for the reduction of rectal to urethral microbial spread. They can be used as infusions or the essential oils can be diluted in tea or warm water. Ingredients for a sample peri-rinse are provided in Table 9-1 (also see Chapter 3). Topical use of these herbs is considered safe during pregnancy.

Cranberry

The use of cranberries (Fig. 9-1) for the treatment of UTI dates back to the mid-nineteenth century when German chemists discovered that consumption of the berries produced a bacteriostatic acid in the urine. By 1900 in the United States, it was postulated that eating cranberries acidified the urine and prevented UTIs.7 This mechanism of action has been questioned as studies have failed to consistently show acidification of the urine with consumption of cranberry juice. There are mixed results regarding the effect of cranberry juice, fruit, and extract on urine pH. It appears that cranberry does not consistently lower urine pH and it is uncertain whether any reduction in urine pH that does occur has an antibacterial effect.8 However, the use of cranberry products continues to be a popular and empirically efficacious means of preventing and treating uncomplicated lower UTI. It is now accepted that the primary mechanism of action of cranberries is caused by two compounds in cranberries that each prevent fimbriated E. coli from adhering to uroepithelial cells in the urinary tract. 9 10 11 These compounds are also found in blueberries, which may also be used as part of the prevention and treatment of UTI.12 Although cranberry has primarily been used against uropathogenic E. coli, recent evidence from in vitro studies suggests that it may have activity against other uropathogenic organisms, and also against H. pylori, responsible for gastric ulcers.13 Cranberry also may prevent the formation of biofilms on epithelial mucosa, reservoirs of bacteria that are difficult to effectively treat with antibiotics.8

Based on a comprehensive review of the literature by the Cochrane Collaboration, there is some evidence from two good-quality RCTs that cranberry juice may decrease the number of symptomatic UTIs in women over a 12-month period. Based on the literature, there have been problems with noncompliance over long periods of administration, probably because of the taste of some cranberry products or possibly other side effects; and the optimum dosage and administration methods (e.g., juice or tablets) are unclear, necessitating further properly designed trials.14 However, clinical experience with cranberry juice products in herbal practice suggests that compliance problems can be overcome by using palatable products. In two good-quality RCTs, cranberry products significantly reduced the incidence of UTIs at 12 months compared with placebo/control in women. One trial gave 7.5 g cranberry concentrate daily (in 50 mL); the other

gave 1:30 concentrate given either in 250 mL juice or tablet form. There was no significant difference in the incidence of UTIs between cranberry juice vs. cranberry capsules.14 The safety of cranberries and their general healthful properties, along with combined empiric evidence of numerous practitioners, suggests that it is reasonable for women with no other significant health problems to use cranberry products for the prevention of recurrent UTI.15 A recent review article on cranberry summarizes that “recent, randomized controlled trials demonstrate evidence of cranberry’s utility in urinary tract infection prophylaxis. … Cranberry is a safe, well-tolerated herbal supplement that does not have significant drug interactions.”16 Recommended daily doses of cranberry for the prevention of UTI vary. Based on the available literature, the therapeutic dose of cranberry juice is 30 to 300 mL daily or three 8-oz glasses of unsweetened juice daily, or one tablet (300 to 400 mg) of cranberry extract tablets twice daily.8,16

Uva Ursi

Uva ursi (Fig. 9-2) is one of the most commonly used urinary tract disinfectants in modern herbal medicine.17 The leaves, taken as a cold or hot infusion, decoction, or tincture, are primarily used as an antiseptic in urinary tract infections.7 Uva ursi is commonly combined with urinary demulcents, such as marshmallow root or corn silk, and also may be taken with an herbal diuretic, most commonly dandelion leaf, but goldenrod or birch

leaf may be used as well. Diuretics are contraindicated in pregnancy. Cold infusion reduces the tannin content of the product, making it easier for the digestive system to handle and reducing the nausea sometimes associated with its use; however, cold preparations might be inadvisable for immunocompromised patients because of the potential for microbial contamination from the herbs. Uva ursi is approved by the German Commission E for the treatment of inflammatory conditions of the urinary tract.18 It is widely used in the treatment of uncomplicated acute and recurrent UTI, based on its astringent and antibacterial actions, and when antibiotics are not deemed essential.19 Midwives include the herb as an astringent anti-inflammatory in sitz baths and perineal rinses for postnatal perineal healing and as part of treatment of vaginitis and urethritis. Unfortunately, there are few clinical trials and pharmacodynamic studies of uva ursi. In vitro studies using crude leaf preparations and extracts of uva ursi leaf have demonstrated mild antimicrobial activity against known UTI-causing organisms including C. albicans, E. coli, S. aureus, and Proteus vulgaris, and others.20 Several studies have also demonstrated anti-inflammatory activity of the herb, particularly enhanced when extracts are used in combination with anti-inflammatory pharmaceutical drugs, such as prednisolone, indomethacin, or dexamethazone.21,22 One double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomized study of 57 women utilized a combination extract of hydroalcoholic extract of uva ursi leaves, standardized to an unknown amount of arbutin and methylarbutin uva ursi with dandelion leaf (Taraxacum officinalis) to evaluate the efficacy of this combination for the prevention of recurrent urinary tract infection. Inclusion in the study required that otherwise healthy individuals had suffered at least three episodes of cystitis in the past year and at least one episode in the last 6 months prior to this study. Patients received either the extract (n = 30) or placebo (n = 27) three tablets three times daily for 1 month and were then followed for 12 months. At the end of the 12-month monitoring period, significantly more women in the placebo group experienced recurrent cystitis compared with the treatment group (p < 0.05). No adverse effects were reported.17,23

Some amount of disagreement can be found in the literature regarding the requirement of an alkaline pH environment for the efficacy of this herb. Some authors postulate that a reduced urinary pH inhibits the efficacy of the herb; others argue that increasing the alkalinity of the urinary environment enhances the efficacy of the herb, while still others state that activity is not dependent on urinary pH. Given the reliability of this herb generally, it is prudent to conclude that if uva ursi does not seem to be working, the addition of four “00” capsules of the equivalent of 1 tablespoon sodium or potassium bicarbonate may be taken once or twice daily, divided between uva ursi doses, to alkalinize the urine in such situations before making a final determination about efficacy.15,19,24,25

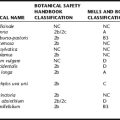

The question of whether this herb is safe for use in pregnancy is difficult to definitely answer based on the available evidence. The Botanical Safety Handbook gives this herb a Class 2b and 2d rating: Not to be used in pregnancy, a caution that is reiterated by many authorities.17,18,26,27 However, the reasons for contraindication are variable and not well supported, ranging from alleged uterotonic and oxytocic activity to “theoretical fetotoxicity.”17,27 The original source of the concern of oxytocic activity appears to stem from Brinker, who reported that there is “empirical” evidence of oxytocic action with no further explanation.28 Low Dog states that the herb has potential fetotoxicity because of its hydroquinone content. Studies using pure hydroquinone (i.e., not the whole herb or whole herb products) have produced microtubulin dysfunction in bone marrow, and exposure of human lymphocytes and cell lines to hydroquinone has been shown to cause genetic damage.15 However, giving pure constituent is not the same as giving a whole herb, a perennial problem in assessing the safety of herbs with conventional pharmaceutical testing models. Although Tyler et al. state that mutagenicity may be associated with this herb, other researchers report on low potential for mutagenicity and negative Ames’ test.17 In animals administered 100 and 400 mg/kg per day of arbutin, no signs of fetal toxicity were observed.17 Uva ursi has been used by midwives as a mainstay treatment of acute symptomatic cystitis in pregnancy for over two decades in the United States with no adverse reports associated with its use.29 Empiric observation demonstrates less recurrence of UTI with uva ursi versus treatment with antibiotics. The transference to infants of arbutin/hydroquinone from uva ursi use during lactation has not been researched and therefore is not recommended by German authorities; however, the risk remains speculative.18 McKenna et al. recommend using only the lowest doses during lactation, observing the infant for side effects, and using under the guidance of a knowledgeable lactation expert.7 It is always prudent to avoid the medical use of herbs during the first trimester unless absolutely necessary. In the case of uva ursi, it is advisable to avoid it entirely during the first trimester, and to use it only if it is the best option for treatment of UTI later in pregnancy, using only at a minimal effective dose and for minimal duration. Further research in this area is clearly needed, particularly given the volume and frequency of UTIs among pregnant women.

Yarrow

In vitro studies of the essential oil and methanol extracts of several species of yarrow found Achillea millefolium to be active against a number of pathogenic organisms including Staphylococcus aureus, Klebsiella pneumoniae, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Salmonella enteritidis, Aspergillus, and Candida albicans, and also to possess antioxidant activity.30,31 Water extracts have also demonstrated antimicrobial activity.32 Two studies, however, while identifying antimicrobial activity in a number of herbs, did not demonstrate antimicrobial activity of yarrow.33,34 The German Commission E lists among its actions antibacterial, astringent, and spasmolytic. No other literature was identified evaluating use of yarrow for UTI. Herbalists typically recommend the tea, 1 cup two to four times daily, for its antimicrobial and mild diuretic effects. Mills and Bone assert that limited use in pregnancy has not been associated with adverse fetal outcomes. Evidence of increased fetal damage in animal studies exists, with unknown relevance to human consumption. Yarrow is generally contraindicated during pregnancy because of its potentially high thujone content and emmenagogic activity.27,35

Demulcent and Anti-inflammatory Herbs

Goldenrod

Goldenrod is an anti-inflammatory, diuretic herb and spasmolytic favored for its beneficial effects in the treatment of UTI, which have been successfully demonstrated in both animal and uncontrolled human trials.19,36 It is described by the German Commission E monographs and ESCOP as used for irrigation therapy for diseases of the lower urinary tract, especially for inflammation, as well as for prevention and treatment of urinary calculi and renal gravel. The flavonoid (including quercetin), saponin, caffeic acid derivatives, and glycosides have been described as the active components.32 Goldenrod is taken as an infusion, 3 to 4 g of dried herb/150 mL water, steeped 10 minutes, taken two to three times daily.19,32 It is suggested to take in conjunction with copious fluids.18,19,32 ESCOP contraindicates the use of European goldenrod in patients with edema because of impaired cardiac or renal function.19 Patients with allergies to plants in the Compositae family should avoid use of this herb. No data are available on use during pregnancy and lactation.

Marshmallow Root

Marshmallow root is soothing and anti-inflammatory to the throat and GI system.19 It is an excellent addition to water extracted uva ursi infusions and decoctions for its demulcent, soothing effects in the treatment of UTI.35 The roots are rich in mucilage, which is composed largely of polysaccharides. Lack of studies on the pharmacodynamics of this herb in the urinary system make it impossible to conclude whether there are direct or indirect effects on the urinary epithelium of the urinary tract, but combination with uva ursi certainly reduces the possible irritation to the GI of the high-tannin content of that herb. Alcohol is not an effective menstruum for extraction of polysaccharides; therefore, only water-based extraction methods are used for this herb.

Antispasmodic Herbs

Discussions of specific antispasmodic herbs are found elsewhere in this book. All of the herbs listed in Table 9-2 as antispasmodics are used specifically for their unique ability to relieve spasms in the pelvic organs, mostly through their action on smooth muscle. Yarrow has mild antimicrobial activity. Kava kava has a reputation for marked action specifically on the bladder, and is especially valued for treatment of neurogenic bladder pain. Yarrow and kava kava are contraindicated in pregnancy and should be used with caution in lactation. See Plant Profiles: Kava kava for specific precautions with its use. Wild yam has been used historically for its ability to ease spasms in the hollow organs, and is considered a valuable herb for the treatment of cramping associated with lower UTI, as are cramp bark and black haw. Black cohosh is specifically indicated for pelvic discomfort and cramping that are also associated with drawing pains in the lower back and legs. See plant profiles: Black Cohosh, for safety consideration. Yarrow may be taken as a tea or infusion, alone or added to other UTI specific herbs, but otherwise these herbs, including yarrow, generally are included in tincture form with other herbs for UTI, typically as 10% to 50% of the formula.

NUTRITIONAL CONSIDERATIONS/ADDITIONAL THERAPIES

Probiotics

There is limited research on the influence of diet on UTI. Midwives and herbalists commonly suggest a reduction in dietary sugar consumption and an increase in fluid intake, with the addition of cranberry juice, as discussed. Because urinary tract infections are often cause by bowel flora, which are pathogenic in the urinary tract, one train of thought is that modification of bowel flora may lead to a reduction in recurrent UTI. 37 38 39 40 The use of probiotics to restore normal vaginal flora, and thus provide a competitive bacterial barrier to uropathogens is emerging as an area of research in the prevention of recurrent UTI.1,13 Proponents of this approach use specific microorganism strains to restore the vaginal lactobacilli microflora such that the indigenous lactobacilli recover, or the patient retains some degree of acidic pH and protection against infection. The basis for use of probiotics emerged from clinical observations in 1973, when a study of healthy women showed an association between lactobacilli presence in the vagina and absence of UTI history. Results from a limited number of studies have demonstrated a significant reduction in recurrence rate of UTI using one or two capsules vaginally per week for 1 year, with no side effects or yeast infections. A two-strain combination is recommended for vaginal use: L. rhamnosus GR-1 is used for its anti-Gram negative activities and resistance to spermicide, and L. fermentum RC-14 is included for anti-Gram positive cocci activities and hydrogen peroxide production. Various protocols have been explored, such as administration postmenses, one or two capsules per week, or one capsule daily for 3 days.37 Studies are needed to determine whether healthy people and those prone to recurrent urogenital infections benefit from daily ingestion of probiotics, such as L. rhamnosus GG, the most clinically documented probiotic strain for gut health. A study using this strain in fermented milk has suggested some reduction in UTI recurrences. The potential for intestinal probiotics to influence bladder and vaginal health through immune modulation has not been fully explored.6 Researchers in one study concluded that dietary habits may be an important risk factor in UTI recurrence. One-hundred thirty-nine women from a health center for university students or from the staff of a university hospital (mean age: 30.5 years) with a diagnosis of an acute UTI were compared with 185 age-matched women with no episodes of UTIs during the past 5 years. Data on the women’s dietary and other lifestyle habits were collected by questionnaire. A risk profile for UTI expressed in the form of adjusted odds ratios (ORs) with 95% CIs was modeled in logistic regression analysis for 107 case control pairs with all relevant information. Frequent consumption of fresh juices, especially berry juices, and fermented milk products containing probiotic bacteria (e.g., yogurt, cultured milk, cheese) was associated with a decreased risk of recurrence of UTI. A preference for berry juice over other juices, and consumption of fermented milk products three times weekly were both associated with a reduction in recurrent UTI.12 The efficacy of probiotics depends on having the proper strains, prepared and stored to maintain their activity. According to Low Dog, a recent analysis of 20 probiotic products claiming to contain specific Lactobacillus species found 30% of products to be contaminated with other organisms, and 20% of products contained no viable species whatsoever.15

Vitamin C

Vitamin C has is used as a bacteriostatic and acidifying agent in the treatment of urinary tract infections. Studies have shown, however, that it actually does not significantly acidify the urine. It is likely, therefore, that it is having a bacteriostatic action through other mechanisms not yet fully elucidated. It was demonstrated by Carlsson et al. that large amounts of a bacteriostatic gas (NO) are formed in mildly acidified nitrite containing human urine and that NO formation is greatly enhanced by the addition of vitamin C. Moreover, mildly acidified nitrite-containing human urine showed antimicrobial activity against three of the most common urinary pathogens and this inhibitory effect was further increased after addition of ascorbic acid.41

CASE HISTORY 1: TREATMENT OF AN UNCOMPLICATED LOWER UTI IN A NONPREGNANT WOMAN

Her protocol is a standard botanical UTI intervention as follows:

INTERSTITIAL CYSTITIS

The syndrome of chronic urinary bladder inflammation, pelvic pain, and frequent urination was dubbed interstitial cystitis (IC) in the 19th century. There is no uniform or pathognomonic histopathologic lesion; rather, IC represents part of a spectrum of irritative pelvic syndromes not clearly resulting from infection.42 Although some patients have ulcerations of the bladder epithelium, these occur in less than 10% of cases. Interstitial cystitis generally affects women beginning around 40 years of age, and also affects men.43 Generally speaking, IC waxes and wanes but does not tend to spontaneously remit except in a minority of patients. Although anxiety, depression, and psychosocial distress (including inability to work owing to pain and frequency of urination) are common accompanying complications, the condition itself does not progress and has no known life-threatening complications.

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

Interstitial cystitis is a multifactorial disorder with no definitively established etiology.42 Connections to allergy or autoimmunity are suspected based on features of the illness and associations with other allergic or autoimmune diseases. In the past decade, research attention has focused on the deterioration of the glycosaminoglycan layer of the bladder epithelium as well as the role of nitric oxide (NO).44,45

DIAGNOSIS AND DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

IC diagnosis is one of exclusion. Other causes of pelvic pain and urinary frequency, including infectious urethritis or cystitis, bladder polyps, bladder cancer, endometriosis, and vaginitis, must be ruled out. Although diagnosis is often presumed based on the clinical picture, cystoscopic examination can help to confirm the diagnosis.42 The presence of glomerulations or a Hunner’s ulcer strongly correlates with interstitial cystitis. Some also consider pain on bladder distention produced by intravesical instillation of water, saline, or potassium solutions, to be diagnostically significant.

CONVENTIONAL TREATMENT

One definitive review of IC sums up conventional treatments for the condition thus: “Although the symptoms of IC can be controlled with one of a variety of treatments in the overwhelming majority of patients, there is little evidence that treatment accomplishes anything more than influencing the symptomatic expression of the disease, rather than curing the condition.”42 There are three categories of standard therapy available: oral, intravesicular, and surgical.

Oral Treatment

Amitriptyline, a tricyclic antidepressant, is one of the most commonly prescribed oral medications for patients with interstitial cystitis. Although apparently effective in uncontrolled trials, no controlled trials have been reported.42 The most common adverse effect of amitriptyline is sedation, and thus it is usually given at bedtime. It is contraindicated in patients with conduction disorders or arrhythmias, unstable angina, congestive heart failure, or orthostatic hypotension. Hydroxyzine and other H1 receptor antagonist antihistamines also have been used, although they are not supported by controlled clinical trials.46 It can take 3 months to see a benefit from these drugs, and they tend to be most effective in patients with allergies.47 The major adverse effect of these drugs is sedation. Pentosan sodium polysulfate is a synthetic glycosaminoglycan administered orally. It has been repeatedly shown to induce remission in approximately 30% of patients who take it, particularly if they have milder symptoms of shorter duration.42,47 It may taken many months for benefits to appear, and many more for optimal effects. The most common adverse effects are nausea, rash, diarrhea, and reversible alopecia.42 Rarely hemorrhage can occur. The final category of oral medications routinely prescribed for patients with interstitial cystitis are nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and opioid analgesics. Nonspecific NSAIDs and cyclooxygenase (COX)-2–specific NSAIDs appear to be equally effective for relief of pain related to interstitial cystitis, although they have not been proved effective for this condition in controlled trials. COX-2 inhibitors are considered safer than nonspecific NSAIDs, but are also dramatically more expensive. Ceiling effects are noted for both types—no added benefit is achieved above a certain dose.42 Both types can cause gastrointestinal bleeding, although COX-2 inhibitors are less likely to do so. Both also have significant renal toxicity. Opioid analgesics, with the significant problems of sedation, respiratory depression, dependence, addiction, and other problems are generally considered a last resort in patients with chronic pain. Unlike NSAIDs, opioids do not have an efficacy ceiling.

Intravesicular Treatment

There are two major intravesicular therapies available: dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) and heparin. Less common intravesical therapies that will not be discussed here include silver nitrate, Clorpactin, and hyaluronic acid. DMSO was the first FDA-approved treatment for interstitial cystitis—interesting as it is a natural product and because no controlled clinical trial data supported its efficacy. Using a solution of 50% DMSO on an outpatient or self-administration basis, approximately 35% of patients go into remission after one to three cycles of treatment.47 Unfortunately the treatment tends to lose efficacy over time. The main adverse effects are acute symptom flare-up for 24 hours after instillation (sometimes compensated for by prior instillation of a topical anesthetic or systemic opioid analgesic) and intense sulfurous odor of breath and body after use. Intravesical heparin requires long-term use (minimum 2 to 6 months) before benefits begin to be noticed, but they can be significant.42 Benefits do not appear to be sustained unless treatment is continued more or less indefinitely. There is no systemic absorption of heparin administered in this fashion and thus no effect on coagulation or bone density.

Surgical Treatment

Hydrodistention is the most common surgical procedure for treatment of people with interstitial cystitis. It consists of anesthetizing the patient, and then distending the bladder with water and holding it in the enlarged state for a period of 15 or more minutes.42 Symptoms are usually immediately relieved after hydrodistention and remain in remission for up to 24 months. However, they almost always return. Repeat treatments can be effective. Controlled clinical trials have not been published. This procedure can help in the diagnosis of interstitial cystitis as it often makes glomerulations or Hunner’s ulcers obvious. Perhaps surprisingly, there is no indication that this treatment results in long-term bladder dysfunction, although there is a significant risk of bladder rupture. For the fewer than 10% of patients who have severe symptoms not relieved by these therapies, more invasive surgery is contemplated.42 These procedures include resection of Hunner’s ulcers, neurotomies, cystectomies, augmentation cystoplasties, and neobladder construction. Results vary considerably and there are many possible adverse effects, necessitating a careful, thorough decision-making process before choosing this method of treatment.

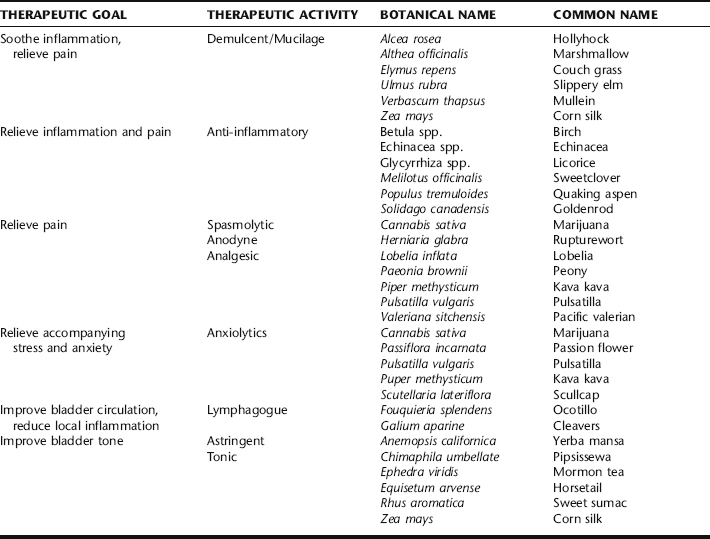

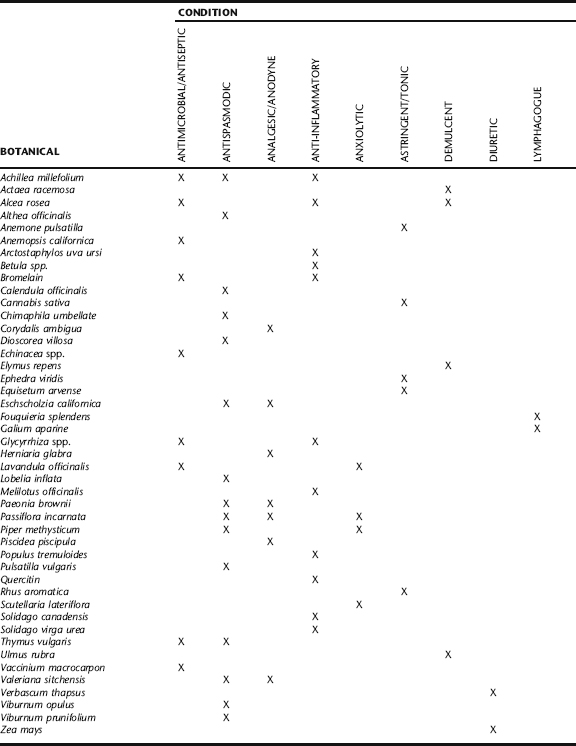

BOTANICAL TREATMENT OF INTERSTITIAL CYSTITIS

A large number of medicinal plants are utilized clinically in patients with IC based on observed botanical actions (Table 9-3). There is a general absence of clinical trials for botanicals for the treatment of this condition. This parallels the fact that many of the pharmaceuticals prescribed for IC patients also have not been subjected to controlled clinical trials. The most important categories of herbs for treatment are mucilaginous or reflex demulcent herbs, anti-inflammatories, anodynes, pelvic lymphagogues, spasmolytics, astringents, anxiolytics, and bladder tonics. Herbs with these actions are aimed at treating underlying causes and pathophysiologic processes as well as alleviating symptoms. Immunologic support (e.g., via use of adaptogens; see Chapter 7) is a potentially important means to successful treatment in patients exhibiting this condition in conjunction with a history of allergies or atopy.

Demulcent Herbs

Herbs rich in complex polysaccharides are believed to induce mucus secretion in the urinary tract after oral administration, possibly through neurological pathways.48 Marshmallow leaf and root, hollyhock leaf and root, couch grass rhizome, slippery elm bark, and cornsilk stigmata are among the many herbs commonly used for this purpose. Many herbal practitioners believe that reflex demulcent herbs such as these may help restore or support the glycosaminoglycan layer and/or epithelium of the bladder, although restoration of the GAG layer is not a definitive treatment.49,50 It is unknown if this action is truly operational in patients with interstitial cystitis, although many patients report at least some symptomatic relief while taking demulcent herbs. The demulcent herbs cited here have no known adverse effects. The usual preparation and dose of each is to stir approximately 1 tbs powder into 4 to 8 oz water, and drink this two to three times daily. This amount of powder also can be taken as capsules. Optionally, 5 to 10 mL of a glycerite can be administered three times daily. These herbs do not work well as tinctures because the polysaccharides are not very soluble in ethanol. These herbs should not be administered simultaneously with other herbs or drugs, because the polysaccharides may alter absorption of many agents.51

Anti-Inflammatory Herbs

Anti-inflammatory herbs are also likely to be important in any botanical approach for patients with IC. The botanical constituent quercetin is the best example supporting the potential benefit of anti-inflammatory herbs. The only botanical medicine that appears to have been studied in a modern clinical trial is the ubiquitous, anti-inflammatory, antioxidant flavonoid, quercetin. In an open trial, 1 g twice daily for 4 weeks brought symptomatic relief to 20 of 22 male and female volunteers with interstitial cystitis.52 There were no adverse effects, although two people dropped out of the study. For acute symptoms, as much as 1 g five times a day of quercetin may be necessary. Often quercetin is combined with bromelain, a plant enzyme complex, on the theory that bromelain enhances absorption of quercetin and because bromelain itself has systemic anti-inflammatory activity that clearly affects the lower urinary tract.53 A typical dose of bromelain is 500 to 1000 mg three times daily between meals. Taking bromelain with food causes it to act as a protease in the digestive tract and may reduce systemic absorption and activity. Many herbs influence multiple inflammatory pathways and also often have other effects on immune cells, as has been well established for echinacea.54 Salicylate-containing herbs are commonly used in countering inflammation, with birch leaf and quaking aspen bark having some specific affinity for the genitourinary tract.55 These herbs have an additional benefit in that they are analgesic. Any of these anti-inflammatory herbs may cause mild digestive upset. Birch and quaking aspen may theoretically inhibit platelet aggregation, although there is no clinical evidence of bleeding with these herbs or interaction with other antiplatelet or anticoagulant agents. Clinical research with the related herb willow cortex shows no significant effect on platelet aggregation in humans.56 Two anti-inflammatory herbs hold a special place in the treatment of people with interstitial cystitis—Glycyrrhiza glabra (licorice) and Glycyrrhiza uralensis (gan cao) root. These plants have been studied in depth and found to have several actions that should have a beneficial effect on interstitial cystitis patients. Licorice and gan cao contain compounds that are anti-inflammatory, immunomodulating, antioxidant, and inhibit abnormal complement. 57 58 59 60 This coupled with the historical use of these herbs to treat inflammatory diseases and inflammatory autoimmune conditions makes them well suited as treatment for interstitial cystitis.

Spasmolytic and Anxiolytic Herbs

One herb that seems to be among the most commonly prescribed for people with interstitial cystitis is Kava kava (Piper methysticum) root. This herb has repeatedly been shown to be an effective anxiolytic in double-blind, placebo-controlled trials.61 Safety concerns regarding kava kava are discussed in Plant Profiles: Kava kava.

Interstitial cystitis, like so many chronic conditions with an inflammatory component, involves the inseparably linked mind and body. To this end, an anxiolytic herb such as kava might be helpful in a psychoneuroimmunologic way. Indeed, a neurogenic hypothesis of the etiology and pathogenesis of interstitial cystitis has recently gained ground.62 Many practitioners ascribe kava’s benefits to the spasmolytic properties of the herb, a theory that correlates with the fact that the bladder of the interstitial cystitis patient often contracts when it reaches a certain, abnormally low point of fullness.62

A typical adult dose of kava tincture for IC treatment is 3 to 5 mL tid. Standardized extracts of this herb are not recommended for use because some use acetone as a solvent, and such concentrated extracts differ sufficiently from the natural state of the herb that cannot be ruled out as a possible cause of the handful of reports of hepatotoxicity. Kava is nonaddictive and nonsedating in small doses. It actually improved mental function compared with diazepam in a clinical trial.63 Because of lack of information it should be avoided in pregnancy and lactation. Pending further study, it should be avoided in patients with pre-existing liver disease or those concomitantly taking hepatotoxic drugs.

Several other spasmolytic botanicals may also help reduce symptoms in patients with interstitial cystitis. These include rupturewort herb, lobelia herb and seed, and peony root. Rupturewort is a safe spasmolytic for use in milder cases but must be used fresh.64 The dose of a fresh-plant tincture is 5 mL tid. If fresh material is available for cold infusion, steep 1 tbs in a cup of water and drink three cups per day. Lobelia is the next strongest spasmolytic and, in the proper dose, is also without adverse effects. Overdose will cause nausea or sometimes even vomiting in most people. The typical dose of tincture is 0.5 to 1 mL tid. Peony or its Asian cousins Paeonia lactiflora (Chinese peony) and P. suffruticosa (tree peony) are in a similar class with lobelia in terms of strength and potential for toxicity. Peony root tends to be helpful for mood disturbances as well as being spasmolytic.65 The same dose as lobelia is used with the same consequences occur with overdose (e.g., nausea).

Lymphagogue and Astringent Activity

Ocotillo is an unusual plant native to the southwestern United States and northern Mexico. There is no modern research on this plant, which clinically acts as the most specific pelvic lymphagogue the author has encountered. It seems to be helpful in all instances of chronic pelvic conditions characterized in traditional herbalism as being “congested,” including interstitial cystitis. Owing primarily to habitat loss and the fact that it is a slow-growing desert plant, ocotillo is potentially threatened in the wild. Therefore, it is important to find a source of sustainably harvested herb. The usual dose of tincture is 3 to 5 mL tid, or smaller doses when combined with other herbs in formulas. Sweet sumach bark of root belongs to the Anacardiaceae family along with its greatly feared cousin, Rhus toxicodendron (poison ivy). Sweet sumach does not contain urushiol and does not cause dermatitis. It is high in tannins and has an astringent effect that appears to be specific to the urinary tract.66 Astringent herbs may be anti-inflammatory and may help tonify the bladder tissue in a way that has not yet been scientifically investigated. Sweet sumach does have a history of use in treating symptoms of interstitial cystitis. The usual dose of tincture is 1 to 2 mL tid. It may cause nausea, in which case it should be taken with food. Mormon tea stem and related native American species in the genus are also used as urinary tract astringents. These species, unlike their Asian cousins (particularly Ephedra sinica or ma huang), do not contain ephedrine or pseudoephedrine.49 They are rich in tannins. Because Mormon tea is also diuretic, it may be irritating to some patients and should not be taken as a tea in most cases. In cases of acute pain episodes, a sitz bath made by adding a handful of Mormon tea herb to the bath water may help relieve symptoms. Mormon tea may cause nausea when taken internally; taking it with food usually eliminates this problem. Yerba mansa root grows exclusively in the desert southwest of the United States and northern Mexico. It also contains tannins and has a strong reputation in Southwestern herbal traditions as a mucus membrane tonic, mild antimicrobial, and as a mild diuretic.49 It also has moderate anodyne effects. Although unrelated to goldenseal, it acts similarly to this useful plant.49 Yerba mansa is considered specific for chronic inflammatory bladder conditions, although it has not been the subject of research.49 The usual dose of tincture is 3 to 5 mL tid. It may cause nausea; taking it with food eliminates this problem. Owing to the limited distribution of this plant in the wild, care should be taken in obtaining it from a sustainable source. All astringent herbs should not be combined with alkaloid-rich herbs or most drugs, as tannins interfere with the absorption of these agents.51

Bladder Tonics

Several nonastringent herbs traditionally have been considered bladder tonics, meaning that they support the urinary bladder in a very general way. They have not been the subject of modern research to determine the mechanisms involved. Pipsissewa herb, horsetail herb, cleavers herb, and mullein root are four such herbs. All four are completely benign, even at large doses. Because they can be diuretic,67 high doses may aggravate some patients with interstitial cystitis. Generally, they are used in lower doses for long periods of time combined with other herbs to promote general healing. Investigation of these widely used, gentle herbs is warranted to determine the degree of efficacy and their actions. A typical dose of tincture of any of these is 2 to 4 mL tid or less when combined with other herbs in formulas. Although these humble herbs do not conform well to the dominant pharmacologic model, their utilities cannot be overstated.

Anodyne/Analgesic Activity

A wide range of herbs are available to reduce pain associated with interstitial cystitis. Of course, the underlying causative aspects of this condition must be treated foremost to help eliminate the cause of pain, but sometimes it is necessary to suppress pain to make a person’s life bearable. The simplest and safest botanical anodynes are herbs normally thought of for relieving insomnia and anxiety—the nervines. These include Pacific valerian root, passionflower leaf, and skullcap leaf and flower. All three are central-acting anodynes and are safe for regular use. There is little research on the analgesic mechanism of these herbs, although preliminary animal studies do support that they are active.68 A typical dose of tincture of these herbs is 3 to 5 mL tid, although higher doses more frequently (up to 10 mL five times a day) are indicated for more serious pain. If sleep problems are a distinct element of a patient’s case, nervines should be taken at bedtime. Some people may become drowsy when taking nervines during the day, but often there is no problem. Some studies show these herbs actually increase daytime alertness by improving sleep quality at night.69 These same studies showed no signs of addiction and no interaction with alcohol, facts that are strongly supported by clinical experience. A much more potent, central-acting analgesic is pulsatilla leaf and flower. Although generally active orally, suggesting possible activity in the central nervous system, the widespread use of topical pulsatilla by native peoples for arthritis and related conditions suggests it also may have local anodyne effects.70 Pulsatilla contains glycosides that although more toxic when fresh are also more active. This author feels that fresh pulsatilla is superior to dried, and simply recommends a lower dose to avoid adverse effects. A typical dose of fresh-plant tincture is three to five drops tid, or more frequently (up to every 2 hours) until the pain is alleviated. Signs of overdose include nausea, weakness, bradycardia, hypotension, mydriasis, paralysis, seizure, or coma. Pulsatilla is contraindicated in pregnancy and lactation.

A more controversial but effective analgesic is marijuana leaf and seed. Clearly, this herb is illegal in most jurisdictions for political reasons, but some patients still consider using it on their own volition, making it important to understand it. Cannabinoids from marijuana have long been known to have central analgesic effects, probably mediated through cannabinoid receptors.71,72 Tetrahydrocannabinol is not the most potent cannabinoid in many animal studies, suggesting the whole herb may be more effective or possibly broader in its activity.73 This concept is supported by other evidence suggesting the whole plant is safer than its constituents in isolation.74 Substantial evidence also shows that cannabinoids and flavonoid compounds in marijuana are anti-inflammatory.75 Marijuana has not been specifically reported to alleviate pain or other symptoms in people with interstitial cystitis.

Relief of Inflammation with Edema

The final category of herbs sometimes used in patients with interstitial cystitis is those that have historically been used to relieve local inflammation with edema. Deer’s tongue leaf and sweet clover herb are two examples. Deer’s tongue has not been researched but has a strong history as a topical, local anti-edema herb. It is recommended as an addition to a sitz bath (approximately half a cup of leaves per bath) for relief of acute symptoms.49 Sweet clover can be used similarly, although it is also safe for internal use with a typical tincture dose being 3 to 5 mL tid. Sweet clover and deer’s tongue both contain coumarin, the non-anticoagulant antiedema compound which, when fermented, gives rise to the vitamin K antagonist compound dicoumarol. An ample body of literature supports the antiedema, anti-inflammatory, and other effects of coumarin.48

NUTRITIONAL CONSIDERATIONS

L-Arginine has been advocated as a potential therapy for interstitial cystitis patients because of the possible role of nitric oxide in the disease. An initial open trial found that 1.5 g daily was helpful at reducing voiding discomfort and pain over 6 months.76 A subsequent open study using 3 to 10 g daily found no effect on symptoms or nitric oxide production over 5 weeks.77 A double-blind trial involving 53 patients who took 1.5 g for 3 months found that it decreased pain intensity significantly compared with placebo, and just barely missed statistical significance in reducing pain frequency and urgency.78 More research is needed by a trial of 1.5 g arginine daily is worth considering in most interstitial patients.

ADDITIONAL THERAPIES

Bladder Retraining

Bladder retraining is an important element of any treatment approach because treatment often does not significantly improve bladder capacity after long-term low-volume voiding.47 It consists simply of determining the average time between urinations, then gradually having the patient increase the interval by small increments each month, usually by 10 to 15 minutes per month. This approach has resulted in more than doubling of voiding intervals in some patients. It should be noted, however, that it will probably only succeed if pain symptoms have first been alleviated.

Stress Reduction

Stress reduction methods of all varieties including regular light exercise, meditation, self-hypnosis, visualization, or regular have been recommended, although their efficacy has not been assessed.79

Sitz Baths, Perineal Massage, and Trigger Point Therapy

Warm sitz baths have also been advocated for pain relief without support from clinical trials. Perineal muscle massage and trigger point therapy have been advocated to relieve pain. In one case series involving 52 women and men (10 with interstitial cystitis and the rest with urgency-frequency syndrome), a series of manual trigger release techniques performed per anus and per vagina weekly or biweekly for 8 to 12 weeks resulted in moderate-to-marked improvement in 70% of participants with interstitial cystitis.80 A similar set of techniques also has been reported to be helpful in a smaller series of four patients with interstitial cystitis.81

Acupuncture and TENS

Acupuncture and transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS) are methods of pain reduction with preliminary support from clinical trials. Needling the spleen 6 point was associated with reduction in frequency, urgency, and dysuria in one case series.82 A case series found that high or low frequency suprapubic TENS applied daily for 30 to 120 minutes was associated with good pain relief or remission of symptoms in 23% of patients with nonulcerative interstitial cystitis and 54% with ulcerative disease.83 A combination of acupuncture and TENS resulted in only minor pain relief in an open trial.84

TREATMENT SUMMARY FOR INTERSTITIAL CYSTITIS

Eclectic Specific Condition Review: Interstitial Cystitis, a Historical Perspective David Winston*