CHAPTER 52 Urethral sphincter incompetence

stress incontinence

Terminology and Definitions

The symptom of incontinence is the complaint of involuntary loss of urine (Abrams et al 2002). However, there are several types of incontinence symptoms. These have been defined by the International Continence Society’s Standardization of Terminology Committee and are shown in Box 52.1. This chapter will focus on ‘stress’ urinary incontinence.

Box 52.1 International Continence Society’s (ICS) standardization of terminology

Other types of incontinence (not specifically defined by the ICS)

Epidemiology

In the epidemiological assessment of the prevalence of incontinence, it is important to define the population because incontinence has been shown to vary with age and race. The prevalence of incontinence in an institutional elderly care setting is much higher than in a community-dwelling young population. Prevalence estimates for the most inclusive definitions of incontinence (e.g. ‘have you ever experienced urinary incontinence’) vary greatly from 5% (van Oyen and van Oyen 2002) to 69% (Swithinbank et al 1999); however, most studies fall within the range of 25–45% (Thomas et al 1980, Yarnell et al 1981, Holst and Wilson 1988, Rekers et al 1992, Lara and Nacey 1994, Hannestad et al 2000).

Another factor which greatly impacts on the prevalence of urinary incontinence is bothersomeness. Swithinbank et al (1999) demonstrated that although urinary symptoms are common among the female population, they are not always perceived as a problem. Stress incontinence was experienced, at least occasionally, by 60% of the women, but only half of them felt that it was a problem.

There is less variation when studies asked about daily incontinence. Three studies conducted in women under 60 years of age reported a prevalence of 4–7% (Burgio et al 1991, Miller et al 2000, Samuelson et al 2000), whilst the prevalence in women over 65 years of age was 4–14% (median 9%) (Wetle et al 1995, Nakanishi et al 1997, Brown et al 1999).

Most epidemiological studies assess all types of urinary incontinence, and few have attempted to assess the prevalence of stress incontinence. Overall, approximately half of all incontinent women have stress incontinence. Hannestad et al (2000) demonstrated that there is a regular rise in the proportion of cases of urge incontinence compared with stress incontinence from the age of 40 years. Hunskaar et al (2004), in a large epidemiological study of 29,500 women in four European countries, demonstrated a similar change in the prevalence of different types of incontinence with age. The relative prevalence of mixed urinary incontinence increased with age and that of stress incontinence decreased.

Pathophysiology

Possible variations in pathophysiology of incontinence can be made considering each of these components of continence (see Chapter 49).

Aetiology

The possible risk factors for stress incontinence are shown in Box 52.2.

Some studies have demonstrated age as a significant risk factor for stress incontinence (Goldberg et al 2003), whilst others have only shown age to be significant in urge incontinence (Nygaard and Lemke 1996, Hannestad et al 2000, Samuelson et al 2000).

There are factors associated with age which may be responsible for incontinence rather than age alone. Resnick (1996) describes these using the mnemonic ‘DIAPERS’: Delerium, Infection, Atrophic changes, Pharmacological, psychological, Excess urine output, Restricted mobility and Stool impaction. Certainly, pharmacological agents such as α-blockers (e.g. doxazosin, an antihypertensive) can cause stress incontinence, and angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors can cause chronic cough which may aggravate stress incontinence.

There has been controversy about the role of oestrogens in the treatment of stress urinary incontinence, and a meta-analysis concluded that oestrogen did not improve the symptoms of stress incontinence (Ahmed Al-Badr Ross et al 2003).

Pregnancy, regardless of the mode of delivery, is associated with an increase in the prevalence of incontinence, although the majority of cases improve in the puerperium. Burgio et al (2003) found that 60% of women experienced urinary leakage during pregnancy, but this decreased to 11% by 6 weeks post partum. However, women who experience incontinence during pregnancy, even if it resolves in the puerperium, are more likely to experience incontinence in later life than those who have not had incontinence in pregnancy (Viktrup and Lose 2001).

In a large study involving over 15,000 women, Rortveit et al (2003) demonstrated that women who had a vaginal delivery were at greater risk of developing stress incontinence in later life compared with women who delivered by caesarean section (odds ratio 2.4). The evidence regarding the impact of other obstetric factors is less clear; however, there is some evidence that use of forceps increases the risk of urinary incontinence (Farrell et al 2001, Nelson et al 2001).

There is good evidence that obesity has a causal role in the development of stress incontinence. Several studies have demonstrated an association between obesity and stress incontinence (Brown et al 1999, Hannestad et al 2000, Viktrup and Lose 2001, Goldberg et al 2003), which has been confirmed by intervention studies of bariatric surgery (Deitel et al 1988, Bump et al 1992) and weight loss programmes (Auwad et al 2008). In the treatment group, there was a reduction of stress incontinence from 61% to 12% (Deitel et al 1988).

Epidemiological studies have demonstrated that the prevalence of stress incontinence is lower in Black African women (27%) compared with White women (61%) (Bump 1993). Thom et al (2006) found similar differences when comparing Black American women with White American women, and they adjusted for age, parity, hysterectomy, oestrogen use, body mass, menopausal status and diabetes. They suggested the presence of a protective factor in Black women.

Inherent differences in connective tissue may predispose to stress incontinence. Young nulliparous premenopausal women with stress incontinence had a decreased collagen I : III ratio compared with controls (Keane et al 1997).

Assessment

The assessment involves history, examination and investigations.

A detailed history is required using language that the patient understands. The International Continence Society has produced a document which standardizes the terminology of lower urinary tract symptoms (Abrams et al 2002), although these are not terms which patients will necessarily understand. The confusion caused by the term ‘stress incontinence’ has been highlighted. It is preferable to use a standardized validated symptom questionnaire to elicit the patient’s symptoms. Terms which are not well understood are usually removed in the validation process. Such tools can be completed by the physician or the patient. They ensure that symptoms are not missed and may help patients to describe symptoms which they find embarrassing.

It is important to ask about the impact of stress incontinence on sexual function. In one study, 68% of women stated that their sex life was affected by their urinary symptoms (Ward and Hilton 2002).

Several validated symptom questionnaires exist, and the main differences are content. Some only address symptoms of stress incontinence; for example, the Severity of Symptoms Index developed by Black et al (1996). Others, such as the Kings Health Questionnaire (Kelleher et al 1997) and the Bristol Female Lower Urinary Tract Symptom (BFLUTS) Questionnaire (Jackson et al 1996), assess all lower urinary tract symptoms, and some assess all pelvic floor symptoms (Barber et al 2001, Radley et al 2006).

Recently published national guidelines in the UK (National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence 2006) and the USA (Agency for Health Care Policy and Research 1992, 1996) even suggested that patients who only had the symptoms of pure stress incontinence could be treated surgically without the need for twin channel cystometry.

Harvey and Versi (2001) evaluated the symptoms and signs of stress incontinence in predicting the presence of urodynamic stress incontinence, and found that the isolated symptom of stress incontinence had a positive predictive value of only 56% for the diagnosis of pure urodynamic stress incontinence. This implies that history alone is not reliable in establishing a diagnosis. In practice, most urogynaecologists and urologists still perform urodynamics prior to surgery. If a detailed symptom questionnaire is used to elicit the history, few patients have ‘pure’ stress incontinence alone.

Some symptom questionnaires, such as BLFUTS and ePAQ (Electronic Personal Assessment Questionnaire), separately assess the degree of bother that each symptom causes and the severity of the symptom (Jackson et al 1996, Radley et al 2006). Epidemiological studies have shown that although symptoms of leakage are very common, occurring in up to 60% of the population, less than half of women are bothered by them (Swithinbank et al 1999). Hence, an assessment of bother is important. The degree to which a symptom causes bother may be specific to the patient’s lifestyle and personality. Each individual patient will have their own expectations about treatment and goals which they hope to achieve. In clinical practice, it is important to establish whether or not the patient’s goals are attainable.

In research or audit, a formal assessment of the impact of incontinence on a patient’s quality of life can be made using a quality-of-life questionnaire. There are a large number of validated quality instruments available. The International Consultation on Incontinence (ICI) has appraised and rated the existing instruments (Donovan and Bosch 2005).

Examination

Physical examination of all patients with stress incontinence is important. Body mass index (BMI; kg/m2) should be recorded because there is good evidence that links incontinence with high BMI (Hannestad et al 2000). General abdominal examination may reveal striae suggestive of underlying collagen disorders. There may also be evidence of benign joint hypermobility with hyperextension of joints. A general assessment of the patient’s mobility and dexterity should be made with a view to considering if they would be capable of performing self-catheterization post operatively if necessary. A general neurological assessment should be performed because the presence of neurological disease may indicate an early need for urodynamics instead of conservative treatment.

Pelvic examination is performed to assess:

The levator ani can be assessed digitally just inside the posterior forchette on the left and right of the midline. The Modified Oxford Scale (Laycock and Jerwood 2001) (Table 52.1) provides a useful grading scale of the muscle, and has been shown to correlate well with surface electromyography and manometry (Haslam 1999).

Table 52.1 The Modified Oxford Scale for pelvic floor muscles (PFM)

| Muscle grade | External observation | Internal examination |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | No indrawing movement of perineal body | No activity detected |

| 1 | A mere flicker of activity | |

| 2 | A weak contraction but no PFM lift | |

| 3 | An indrawing movement of perineal body | A moderate PFM lift but without resistance |

| 4 | A good PFM lift against some resistance | |

| 5 | An ability to lift PFM against more resistance with strong grip of examing finger |

The presence of prolapse should be documented using a standardized assessment such as the pelvic organ quantification system (POP-Q) (Bump et al 1996). The advantage of POP-Q is that it has been shown to be reproducible.

Investigations

Pad tests

The main use of pad tests is to assess the outcome of treatment or to demonstrate urine loss. There are two types of pad test: short (≤2 h in duration) and long (>24 h). Although the only standardized test is the International Continence Society’s 1-h pad test, its use as an outcome measure is limited due to its poor reliability. Simons et al (2001) demonstrated that test–retest reliability of the 1-h pad test over a period of 3–10 days, even when similar bladder volumes were used, was clinically inadequate as the first and second pad test could differ by −44 to +66 g.

The report from the second ICI (Artibani and Cerruto 2005) concluded that 24-, 48- and 72-h pad tests had better reproducibility than the 1-h test. Compliance decreases with increasing duration of the test, and for this reason, extending the test beyond 24 h was not recommended. A pad weight gain of 1.3 g or more was considered a positive test. Attempts have been made to objectively quantify the severity of incontinence using pad tests, but there was poor correlation between the short duration tests and subjective assessments of severity (Reid et al 2007). Correlation with the 24-h pad test was only moderate (Sandvik et al 2006). Pad tests cannot be used to diagnose the type of incontinence.

Pyridium pad test

Pyridium (phenozopyridine hydrochloride) is a compound which, when ingested, causes urine to be dyed a bright yellow/orange colour. This test can be useful to determine if the leakage experienced is urine. The test needs to be performed very carefully due to the high risk of false-positive results from perineal staining after voiding. Nygaard and Zmolek (1995) reported nearly 100% Pyridium staining in asymptomatic women during exercise; however, the mean stained area was only 2.6 mm. Some women who have excessive vaginal discharge perceive this to be urine. A Pyridium test can be useful to distinguish the two conditions.

Urodynamics

Urodynamics are discussed in detail in Chapter 51. It has not yet been proven that preoperative evaluation of women with stress urinary incontinence improves the outcome of surgery. Despite this, urodynamic studies are regularly used to assess women with stress urinary incontinence in an attempt to identify preoperative risk factors for failure or postoperative voiding dysfunction. The presence of detrusor overactivity, ISD and voiding dysfunction are theoretically associated with lower cure rates. However, the ability to measure these parameters reliably using current urodynamic techniques remains debatable, and there is little robust evidence that diagnosis of these factors should alter surgical management. There is no agreed definition of ISD. Two commonly used definitions are a maximum urethral closure pressure (MUCP) of less than 20 cmH2O and Valsalva leak point pressures (VLPP) of less than 60 cmH2O; however, both have limitations. MUCP is a measurement made at rest, not during the dynamic stress phase. Although VLPP is a measure of pressure in the dynamic phase during ‘stress’, there is variation in the pressures recorded depending on catheter size, patient position and bladder volume. Another significant problem with VLPP is that up to 66% of women with stress incontinence experience leakage on coughing but do not leak with Valsalva (Sinha et al 2006).

Treatment

Conservative treatment

Patients with stress incontinence may benefit from lifestyle advice. They should be encouraged to maintain a normal BMI. There is evidence that obesity is an independent risk factor for incontinence, and that weight loss in the morbidly (Deitel et al 1988, Bump et al 1992) and moderately (Subak et al 2002, Auwad et al 2008) obese will improve incontinence.

There is some evidence of an association between chronic straining due to constipation and pelvic floor damage which increases the risk of incontinence (Diokno et al 1990, Spence-Jones et al 1994). However, there have been no intervention trials of the treatment of straining and urinary incontinence.

Pelvic floor muscle training

Pelvic floor muscle training (PFMT) was introduced by Kegel in the 1950s to address urinary incontinence in women (Kegel 1951). Patient education is a vital component to PFMT. The strength of pelvic floor muscle contraction should be assessed at the time of pelvic examination. On simple verbal command to squeeze their pelvic floor muscles around the examiner’s fingers, many women are unable to do so, or they inadvertently contract their abdominal or gluteal muscles. Some women will even perform a Valsalva manoeuvre when asked to perform pelvic floor exercises. The pelvic examination provides an opportunity to teach the patient which muscles she needs to strengthen. Bump et al (1991) underscored the importance of education in a study in which women were given only verbal or simple written instructions to perform PFMT; 50% of the subjects were unable to perform a correct pelvic floor contraction despite their perception that they were doing so.

A large randomized controlled trial of PFMT vs no treatment in women with urodynamic stress incontinence demonstrated that self-reported cure is more likely following PFMT than no treatment (relative risk 16.8, 95% confidence interval 2.37–119.04) (Bo et al 1999).

There are very few long-term follow-up studies of PFMT. However, Lagro-Janssen and van Weel (1998) reported 5-year follow-up data on 101 of 110 women. Seven women had undergone surgery, five declined further follow-up and one had become pregnant. The results showed that the proportion of women who were dry (25%) was similar after 5 years, although the number with severe incontinence increased from 3% to 18%. Sixty-seven per cent of women remained satisfied with the outcome of treatment and did not want further treatment. Women with urge or mixed incontinence were less likely to be satisfied than women with stress urinary incontinence. Nearly half of the women (43%) who had received PFMT were no longer training at all. Logistical regression was used at 5 years to determine the relationship between age, parity, anxiety, incontinence severity, adherence to PFMT and treatment success. The only factor significantly associated with better outcome at 5 years was continued PFMT.

A Cochrane review published in 2006 investigated the effects of pelvic floor muscle training for women with urinary incontinence in comparison with no treatment, placebo or sham treatments, or other inactive control treatments (Hay-Smith and Dumoulin 2006). Six trials were included in the review, involving 403 women. The review concluded that there was some support for the widespread recommendation that PFMT be included in first-line conservative management programmes for women with not only stress urinary incontinence but also urge or mixed incontinence.

Biofeedback can be used to maximize rehabilitation in patients who have difficulty in performing pelvic floor contractions. Biofeedback is any signal, auditory or visual, which tells the patient that she is contracting the correct muscles. Simple verbal affirmation of a good pelvic floor muscle contraction at the time of pelvic examination is a form of biofeedback. More sophisticated forms include perineometers that consist of a rectal or vaginal probe, a visual or auditory analogue signal and abdominal electromyography electrodes. When the patient correctly contracts her pelvic floor, an analogue signal through the probe tells her she is utilizing the proper muscles. Similarly, an auditory signal via the electromyogram tells her to what degree, if any, she is recruiting her abdominal muscles. Biofeedback in addition to PFMT has been shown to be no more effective than PFMT on its own (Castleden et al 1984, Burns et al 1993); however, the group sizes were small and no trials specifically addressed the use of biofeedback in patients who could not perform a pelvic floor contraction at initial assessment.

Weighted vaginal cones represent another form of biofeedback (Figure 52.1). In theory, when a weighted cone is inserted into the vagina, the pelvic floor needs to contract to prevent it from slipping out. The patient places the lightest cone in the vagina for 15 min twice daily and goes about her normal activities. She has to contract her pelvic floor muscles to keep the cone from falling out of her vagina. When this weight becomes easy to manage, she exchanges this cone for the next heaviest. The weight of the cone is gradually increased.

A Cochrane review concluded that although limited evidence is available, it suggests that cones benefit women with stress urinary incontinence compared with no active treatment. Meta-analysis of eight trials found cones and PFMT to be no different in terms of subjective cure or improvement, pad test or pelvic muscle strength; however, PFMT was associated with a significantly greater reduction in the number of leakage episodes per day (Herbison et al 2002).

Devices

The use of mechanical devices to control incontinence has been recorded since ancient Egyptian times; various elaborate but cumbersome and uncomfortable devices have been developed (Edwards 1970, Bonnar 1977). Most devices either occlude the urethra, being placed either within the urethra or over the external meatus, or are inserted into the vagina, and provide occlusive pressure against the urethra.

A Cochrane review of mechanical devices reported on six randomized controlled trials. These assessed three intravaginal and three intraurethral devices. Five of the six included studies had a very small sample size and were not large enough to detect a difference reliably. There was a lack of evidence to suggest that the use of mechanical devices is better than no treatment. There was insufficient evidence to favour one device over another, and no evidence to compare mechanical devices with other forms of treatment (Shaikh et al 2006).

Pharmacotherapy

The only pharmacological agent recommended for use in the management of stress urinary incontinence by the ICI in 2005 was duloxetine, a serotonin and noradrenaline reuptake inhibitor. Duloxetine inhibits the presynaptic reuptake of serotonin and noradrenaline in the motor neurones of the pudendal nerve, which increases the amount of these transmitters in the synapse which, in turn, increases pudendal nerve stimulation of the striated urethral sphincter. A systematic review by Mariappan et al (2007) describes the nine randomized controlled trials published comparing duloxetine with placebo. All nine trials were supported by the manufacturer of duloxetine, Eli Lilly. A total of 3066 women were randomized to duloxetine (n = 1712) and placebo (n = 1354). Subjective cure and improvement of incontinence were higher in the duloxetine arms than the placebo arms, but the differences were small and only three additional patients per 100 treated were improved. The withdrawal rate was 17% in the duloxetine group and 4% in the placebo group, and approximately 75% of withdrawals were directly attributable to duloxetine. The most commonly reported side-effects were nausea, fatigue, dry mouth, insomnia, constipation, dizziness and somnolence.

Vella et al (2008) studied a group of 228 women for up to 1 year after they were commenced on duloxetine for moderate stress incontinence. After 4 weeks, only 31% were continuing with duloxetine, 45% had discontinued it due to side-effects, and 24% had discontinued it due to lack of efficacy. At 12 months, only 9% remained on treatment. Another interesting finding of this study was that 5% of women stopped taking duloxetine after 6–12 months and remained dry. This could be due to increased bulk or strength of striated muscle, or spontaneous improvement which may reflect the natural history of incontinence.

Surgical treatment

Importance of evidence-based practice: an historical perspective

Surgical procedures to treat urinary incontinence have been reported for nearly 150 years. Initially, new operations were published as single case reports. These usually included a description of the operation and the surgeon’s opinion of the value of the procedure. If an outcome was assessed, it was frequently prior to discharge, invariably successful and there were no reported complications (Brown 1864, Gilliam 1896).

In 1914, Kelly and Dumm reviewed the literature on surgery for urinary incontinence; 14 studies were included in the review. There was no documented evidence of the failure of any of the procedures. Kelly and Dumm described a new operative procedure, stating that it was more successful than any proposed previously (Kelly and Dumm 1914). The study represented a significant advancement in the reporting of the outcome of surgery for incontinence. Not only did it report a greater number of cases, a series of 20, but failures were also reported. Another notable change was the reporting of both short- and long-term outcomes. Follow-up was greater than 1 year in 13 of the 20 cases. The results of this series are shown in Table 52.2 and suggest that the operation’s efficacy decreased with time. Although this trend was not noted in the report, Kelly and Dumm (1914) did criticize the short follow-up period of 5 months in a series of five patients reported by Dudley in 1895, possibly indicating a recognition that failure increases with time after surgery.

| Outcome | At discharge | Follow-up (1–12 years) |

|---|---|---|

| Cured | 15 | 4 |

| Improved | 4 | 6 |

| Failed | 1 | 3 |

| Lost to follow-up | – | 3 |

| Total | 20 | 16 |

Source: Kelly H, Dumm W 1914 Urinary incontinence in women, without manifest injury to the bladder. Surgery, Gynecology and Obstetrics 18:444–450.

Other factors may have influenced the widespread adoption of Kelly and Dumm’s operation; it may have been related to the relative simplicity of the procedure, or due to Kelly’s general credibility, high standing and influence in the field of urology and gynaecology. Possibly, his charismatic championing of the procedure promoted its adoption (Nation 1997).

In 2009, the ICI report stated that there was enough evidence from randomized controlled trials to indicate that anterior colporrhaphy should not be used in the management of stress urinary incontinence alone (Grade A) (Smith et al 2009).

Over the last 10 years, there has been a significant change in the types of operation performed for urodynamic stress incontinence. Midurethral slings have become the most frequently performed procedure. Furthermore, the overall number of continence procedures performed in the UK has increased by 25%, from approximately 8000 per annum in 1994 to 10,000 in 2005 (Hilton 2008). The reason for this is unknown but it may be due to increased awareness among women and healthcare professionals that incontinence can be treated. However, it could be that the relative technical simplicity of midurethral slings has reduced clinicians’ threshold for surgical intervention.

It is important that new procedures are assessed using robust scientific evidence. The 2008 ICI report reviewed surgical intervention for stress incontinence. The categorization of levels of evidence used by the ICI was the International Consultation on Urological Disease (ICUD) modification of the Oxford System summarized in Box 52.3. A summary of the recommendations for each operation is given in Table 52.3.

Box 52.3 Modified Oxford System

Table 52.3 2009 International Consultation on Incontinence recommendations for surgery for stress urinary incontinence

| Procedure | Recommended | Not recommended |

|---|---|---|

| Burch: open | A | |

| Burch: laparoscopic | B | |

| Tension-free vaginal tape | A | |

| Transobturator tapes | A | |

| Bladder neck sling: autologous fascia | A | |

| Bulking agents | B | |

| Anterior colporrhaphy | A | |

| Transvaginal bladder neck sling (needle) | B | |

| Paravaginal | B | |

| MMK | B | |

| Bladder neck sling: other | D | D |

MMK, Marshall–Marchetti–Krantz.

Burch colposuspension

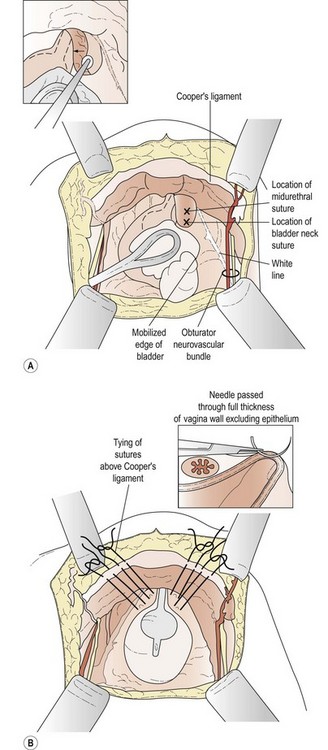

In 1949, Marshall et al reported the empirical observation that suturing the periurethral tissues to the pubic bone alleviated stress urinary incontinence (Marshall et al 1949; Figure 52.2). The Burch procedure was developed as a modification of the Marshall–Marchetti–Krantz (MMK) procedure in 1961 (Burch 1961). The purpose is to return the bladder neck to an intra-abdominal location so that it encounters the same transmural pressure as the bladder during rises in intra-abdominal pressure.

Source: Karram MM, Baggish MS (eds) 2001 Atlas of Pelvic Anatomy and Gynecologic Surgery. Harcourt, New York.

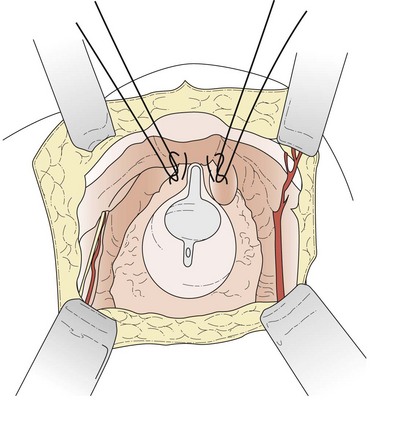

The patient is placed in the dorsal lithotomy position to permit access to the vagina. A transverse suprapubic incision is made and the rectus abdominis is divided along its midline raphe. The surgeon’s hand is then passed beneath the rectus muscles above the peritoneum in the direction of the pubic symphysis; blunt dissection in this fashion opens the retropubic space. The operation can be performed with the peritoneum opened or closed. Once the retropubic space is exposed, the bladder neck is identified with the operator’s non-dominant hand in the vagina using a Foley balloon as a guide. A swab on a stick is then used to sweep the fatty and vascular tissue off the periurethral fascia, while the vaginal fingers elevate the anterior vagina (Figure 52.3A). Keeping the vaginal fingers elevated, the surgeon is then able to take a full-thickness bite of tissue, excluding the vaginal mucosa if possible. At least two sutures are placed on both sides of the bladder neck, one 2 cm lateral to the urethrovesical junction and the other 2 cm lateral to the proximal urethra. Each suture is then passed through the ipsilateral iliopectineal ligament (Cooper’s ligament) on the posterolateral surface of the pubic bone (Figure 52.3B). Care should be taken not to overelevate the urethrovesical junction.

Source: Karram MM, Baggish MS (eds) 2001 Atlas of Pelvic Anatomy and Gynecologic Surgery. Harcourt, New York.

Evidence of the effectiveness of laparoscopic colposuspension

In 1991, Vancaillie described a laparoscopic approach for Burch colposuspension (Vancaillie and Schuessler 1991). Laparoscopic colposuspension is comparable with open colposuspension when performed by experienced laparoscopic surgeons (EL 1/2). Studies demonstrate equal or higher cure rates with the TVT procedure (EL 1/2), and the operation time for the TVT procedure is shorter and the recovery is faster (EL 1/2). The 2008 ICI report recommended that laparoscopic colposuspension was an option for the treatment of stress incontinence (Grade B), but added the caveat that it should only be performed by experienced laparoscopic surgeons (Grade D).

Tension-free vaginal tape procedure

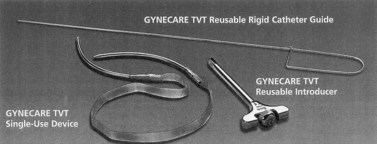

The TVT procedure was developed by Petros and Ulmstem (1993) and Ulmstem et al (1996) (Figure 52.4). The TVT was designed to place the sling around the midurethra, where the pubourethral ligaments are assumed to insert, rather than at the bladder neck where previous slings (e.g. Aldridge slings) were placed.

Ulmstem et al (1996) described insertion under sedation, with a premedication of 5 mg ketobemidone i.m., 0.05 mg fentanyl i.m. at the start of surgery and then prior to insertion of the sling. Up to 5 mg of midazolam i.v. was used during the operation. The bladder was emptied with a Foley catheter. Close to the superior rim of the pubic bone, two 1-cm-long transverse incisions 3 cm either side of the midline are made after injection of local anaesthetic. Between 60 and 70 ml of local anaesthetic (prilocaine and adrenaline 0.25%) is injected in the abdominal skin just above the symphysis pubis and down along the back of the pubic bone to the space of Retzius. Vaginally, 40 ml of prilocaine and adrenaline 0.25% is injected into the vaginal wall sub- and paraurethrally. An incision up to 1.5 cm long is made in the midline of the suburethral vaginal wall, starting 0.5 cm from the outer urethral meatus. Laterally from this incision, a blunt dissection 0.5–1 cm long is made with the scissors either side of the urethra to allow introduction of the TVT needle. A stent is inserted into the Foley catheter to deviate the urethravesical junction away from the path of the needle. The TVT needle perforates the urogenital diaphragm and is brought up to the abdominal incision, ‘shaving’ the back of the pubic bone. The procedure is then repeated on the other side, and then a cystoscopy is performed to exclude perforation; with 300 ml of saline in the bladder, the patient is asked to cough vigorously to ensure that she is dry. Importantly, the sling is only loosely placed without elevation. The plastic sheath which covers the tape is then removed, the tape is trimmed at the abdominal incisions and the incisions are closed. Ulmsten et al (1996) recommended that a size 7 Hegar dilator should be insterted into the urethra to check that the ‘proximal urethra and bladder neck has an acceptable lumen and mobility’.

Evidence of the effectiveness of the tension-free vaginal tape procedure

The TVT procedure is more effective than the SupraPubic ARC (SPARC) procedure (EL 2), and the intravaginal slingplasty procedure is comparable to the TVT procedure in terms of efficacy but has a higher complication rate (EL 2) (Smith et al 2008).

Transobturator tape procedure

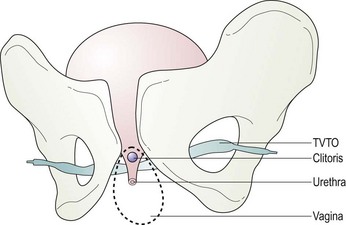

In 2001, Delorme described a new procedure using transobturator tape based on the principles of the TVT procedure, but designed to avoid the risk of bladder perforation (Ward and Hilton 2002) and the rare complication of bowel perforation (Leboeuf et al 2003). Instead of passing the tape through the retropubic space, it is inserted via the obturator foramen. Delorme described an outside-in technique in which the tape is introduced through the skin of the groin, obturator foramen and out of the vaginal incision (Delorme 2001) (Figure 52.5).

Evidence of the effectiveness of the transobturator tape procedure

To date, two meta-analyses of transobturator tape procedures have been published and both concluded that there was limited evidence (Latthe et al 2007, Sung et al 2007). No objective outcomes were reported in the meta-analysis because these were only reported in one randomized controlled trial. The analysis by Latthe et al (2007) considered the two different routes of transobturator tapes and excluded SPARC retropubic tapes. When compared with the TVT procedure, the subjective cure of stress urinary incontinence was slightly worse in the TVT obturator procedure, inside-to-out group (odds ratio 0.69, 95% confidence interval 0.42–1.14), although this was not statistically significant. The transobturator tape procedures were associated with fewer bladder injuries and voiding difficulty than the TVT procedure, but more groin pain and vaginal mesh erosion (Latthe et al 2007).

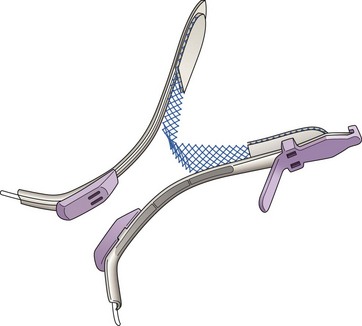

Minitape procedures

A number of manufacturers have developed minitapes or single incision slings (SISs). They only require a vaginal incision. Potentially these SISs could be inserted under local anaesthetic as an office procedure; however, there is currently inadequate data to use these tapes outside of a research setting. Figure 52.6 shows the TVT Secur, the first of these minitapes.

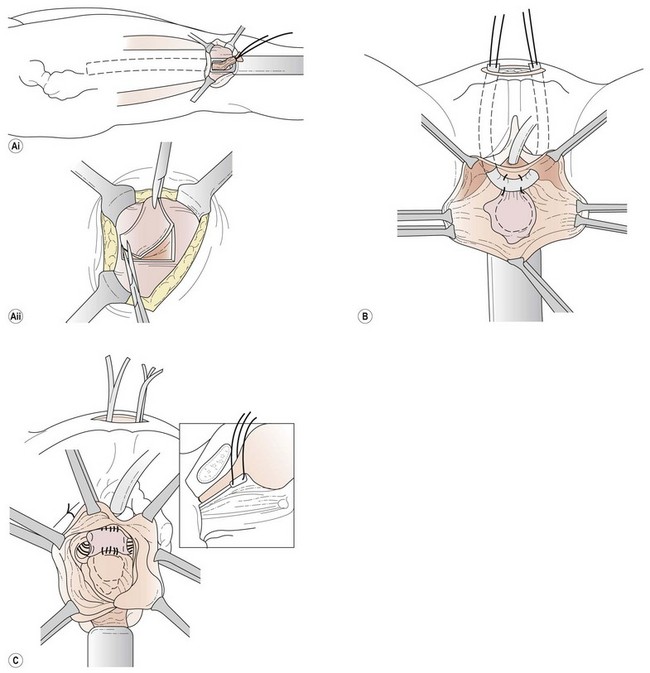

Bladder neck sling procedures

Slings are performed with the patient in the dorsolithotomy position. A horizontal incision is made approximately 2 cm above the pubic symphysis. The subcutaneous fat is dissected, providing visualization of the rectus fascia. If rectus fascia is to be harvested from the patient, the incision may need to be longer. An alternative source of sling material is fascia lata that is obtained from the patient’s thigh by excision or the use of a fascial stripper (Figure 52.7A). Once a 4 × 4 cm piece (for a patch-type sling) or two 2 × 8 cm portions (which are sewn end to end to create a long enough graft for a full-length sling) of fascia have been excised, the defect is closed with delayed absorbable suture. If the patient permits, cadaveric donor fascia can be used. It saves time, is abundant and risk is minimal. The fascia is kept in saline until it is required.

Source: Karram MM, Walters MD (eds) 1999 Urogynecology and Reconstructive Pelvic Surgery, 2nd edn. Mosby, St Louis.

When placing a full-length sling, the central portion of the graft is sewn in place at the level of the bladder neck with an absorbable suture. Each end of the sling is then pulled up through the retropubic space using the previously passed instruments (Figure 52.7B). Once the end of the graft is above the level of the abdominal rectus fascia, it is either sewn to the fascia on either side or in the midline to the other end of the graft. For patch slings, the tissue is folded or trimmed to the correct size then sewn in place at the bladder neck (Figure 52.7C). A permanent suture is then fixed to either side of the patch and the ends are pulled up through the retropubic space to the abdominal incision, as described for the full-length sling. Similarly, the ends of the permanent suture can be tied to one another across the midline. Alternatively, the Stamey needle can be passed through the rectus fascia in two different locations on both sides (a total of four passes), and each end of the permanent suture can be brought up through its own tract. The two left ends are tied to one another on the left side and the two right ends are tied on the right.

Urethral bulking agents

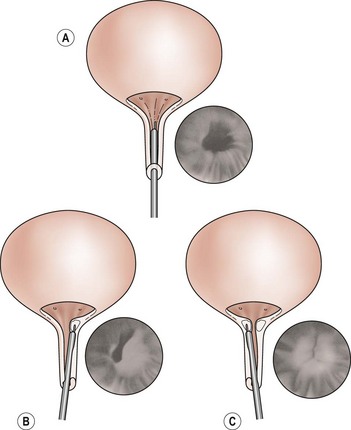

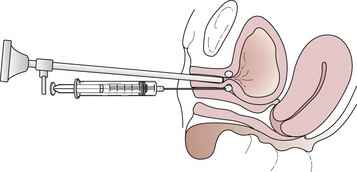

For over 70 years, urethral bulking agents have been used for the treatment of stress urinary incontinence. They are injected transurethrally (Figure 52.8) or periurethrally (Figure 52.9) under direct cystoscopic guidance or through a guidance device.

Source: Karram MM, Walters MD (eds) 1999 Urogynecology and Reconstructive Pelvic Surgery, 2nd edn. Mosby, St Louis.

Figure 52.9 Technique for periurethral injection of urethral bulking agents.

Source: Karram MM, Walters MD (eds) 1999 Urogynecology and Reconstructive Pelvic Surgery, 2nd edn. Mosby, St Louis.

Evidence of the effectiveness of periurethral injection therapy

A Cochrane review in 2007 stated that the evidence was inadequate to inform practice; however, injection therapy may represent a useful option for short-term symptomatic relief amongst selected women with comorbidity that precludes anaesthesia (Keegan et al 2007).

KEY POINTS

Abrams P, Cardozo L, Fall M, et al. The standardisation of terminology of lower urinary tract function. The International Continence Society Committee on Standardisation of Terminology. Neurourology and Urodynamics. 2002;21:167-178.

Agency for Health Care Policy and Research. Clinical Practice Guideline: Urinary Incontinence in Adults. No. 92-0682. US Department of Health and Human Services, Rockville, MD, 1992.

Agency for Health Care Policy and Research. Clinical Practice Guideline: Urinary Incontinence in Adults. No. 96-0682. US Department of Health and Human Services, Rockville, MD, 1996.

Ahmed Al-Badr Ross S, Soroka D, Durtz H. What is the available evidence for hormone replacement therapy for women with stress incontinence? Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology Canada. 2003;25:567-574.

Artibani W, Cerruto M. Imaging and other investigations. International Consultation on Incontinence, Monaco. Plymouth, MA: Health Publication Ltd; 2005.

Auwad W, Steggles P, Bombieri L, Waterfield M, Wilkin T, Freeman R. Moderate weight loss in obese women with urinary incontinence: a prospective longitudinal study. International Urogynecology Journal and Pelvic Floor Dysfunction. 2008;19:1251-1259.

Barber M, Kuchibhatla MN, Pieper CF, Bump RC. Psychometric evaluation of 2 comprehensive condition specific quality of life instruments for women with pelvic floor disorders. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2001;185:1388-1395.

Black N, Griffiths J, Pope C. Development of a symptom severity index and a symptom impact index for stress incontinence in women. Neurourology and Urodynamics. 1996;15:630-640.

Bo K, Taleth T, Holme I. Single blind RCT of pelvic floor exercises, electrical stimulation, vaginal cones and no treatment in the management of genuine stress incontinence in women. BMJ (Clinical Research Ed.). 1999;318:487-493.

Bonnar J. Silicone vaginal appliance for control of stress incontinence. The Lancet. 1977;2:1161.

Brown B. Clinical lectures on diseases of women remediable by operation. The Lancet. 1864;83(2114):263-266.

Brown JS, Grady D, Ouslander JG, Herzog AR, Varner RE, Posner SF. Prevalence of urinary incontinence and associated risk factors in postmenopausal women. Heart & Estrogen/Progestin Replacement Study (HERS) Research Group. Obstetrics and Gynecology. 1999;94:66-72.

Bump RC. Racial comparisons and contrasts in urinary incontinence and pelvic organ prolapse. Obstetrics and Gynecology. 1993;81:421-425.

Bump RC, Hurt WG, Fantl JA, Wyman JF. Assessment of Kegel pelvic muscle exercise performance after brief verbal instruction. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 1991;165:322-327.

Bump RC, Sugerman HJ, Fantl JA, McClish DK. Obesity and lower urinary tract function in women: surgically induced weight loss. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 1992;167:392-397.

Bump R, Mathiasson A, Bo K. The standardization of terminology of female pelvic organ prolapse and pelvic floor dysfunction. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 1996;175:10-17.

Burch J. Urethrovaginal fixation to Cooper’s ligament for correction of stress incontinence, cystocele and prolapse. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 1961;81:281-290.

Burgio K, Matthews K, Engel B. Prevalence, incidence and correlates of urinary incontinence in healthy middle age women. Journal of Urology. 1991;146:1255-1259.

Burgio KL, Zyczynski H, Locher JL, Richter HE, Redden DT, Wright KC. Urinary incontinence in the 12-month postpartum period. Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2003;102:1291-1298.

Burns PA, Pranikoff K, Nochajski TH, Hadley EC, Levy KJ, Ory MG. A comparison of effectiveness of biofeedback and pelvic muscle excercise treatment of stress incontinence in older community dwelling women. Journal of Gerontology. 1993;48:M167-M174.

Castleden C, Duffin H, Mitchell E. The effect of physiotherapy on stress incontinence. Age and Ageing. 1984;13:235-237.

Deitel M, Stone E, Kassam HA, Wilk EJ, Sutherland DJ. Gynecologic-obstetric changes after loss of massive excess weight following bariatric surgery. Journal of the American College of Nutrition. 1988;7:147-153.

Delorme E. Transobturator urethral suspension: mini-invasive procedure in the treatment of stress incontinence in women. Progres en Urologie. 2001;11:1306-1313.

Diokno AC, Brock BM, Herzog AR, Bromberg J. Medical correlates of urinary incontinence in the elderly. Urology. 1990;36:129-138.

Donovan JL, Bosch R. Symptom and quality of life assessment. International Consultation on Incontinence, Monaco. Plymouth, MA: Health Publication Ltd; 2005.

Dudley E 1895 Transactions of the American Gynecological Society xxx: 3.

Edwards L. Mechanical and other devices. In: Urinary Incontinence. London: Academic Press; 1970:115-127.

Farrell S, Allen V, Baskett T. Parturition and urinary incontinence in primiparas. Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2001;97:350.

Gilliam T. An operation for the cure of incontinence of urine in the female. American Journal of Obstetrics. 1896;33:177-182.

Goldberg RP, Kwon C, Gandhi S, Atkuru LV, Sorensen M, Sand PK. Urinary incontinence among mothers of multiples: the protective effect of cesarean delivery. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2003;188:1447-1450.

Hannestad YS, Rortveit G, Sandvik H, Hunskaar S. A community based epidemiological survey of female urinary incontinence: the Norwegian EPINCORT study. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology. 2000;53:1150-1157.

Harvey M, Versi E. Predictive value of clinical evaluation of stress urinary incontinence: a summary of the published literature. International Urogynaecology Journal. 2001;12:31-37.

Haslam J. Evaluation of Pelvic Floor Muscle Assessment: Digital, Manometric and Surface Electromyography in Females. Manchester: MPhil Thesis, University of Manchester; 1999.

Hay-Smith E, Dumoulin C 2006 Pelvic floor muscle training versus no treatment or inactive control treatments, for urinary incontinence in women. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 1: CD005654.

Herbison P, Plevnik S, Mantle J 2002 Weighted vaginal cones for urinary incontinence. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews CD002114(1).

Hilton P. Long-term follow-up studies in pelvic floor dysfunction: the Holy Grail or a realistic aim? BJOG: an International Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2008;115:135-143.

Holst K, Wilson P. The prevalence of urinary incontinence and reasons for not seeking treatment. New Zealand Medical Journal. 1988;101:756-758.

Hunskaar S, Lose G, Sykes D, Voss S. The prevalence of urinary incontinence in women in four European countries. BJU International. 2004;93:324-330.

Jackson S, Donovan J, Brookes S, Eckford S, Swithinbank L, Abrams P. The Bristol Female Lower Urinary Tract Symptoms questionnaire: development and psychometric testing. BJU International. 1996;77:805-812.

Karram MM, Walters MD, editors. Urogynecology and Reconstructive Pelvic Surgery, 2nd edn, St Louis: Mosby, 1999.

Karram MM, Baggish MS, editors. Atlas of Pelvic Anatomy and Gynecologic Surgery. New York: Harcourt, 2001.

Keane DP, Sims TJ, Abrams P, Bailey AJ. Analysis of collagen status in premenopausal nulliparous women with genuine stress incontinence. BJOG: an International Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 1997;104:994-998.

Keegan PE, Atiemo K, Cody J, McClinton S, Pickard R 2007 Periurethral injection therapy for urinary incontinence in women. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 3: CD003881.

Kegel A. Physiological therapy for urinary stress incontinence. Journal of the American Medical Association. 1951;146:915-917.

Kelleher CJ, Cardozo LD, Khullar V, Salvatore S. A new questionnaire to assess the quality of life of urinary incontinent women. BJOG: an International Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 1997;104:1374-1379.

Kelly H, Dumm W. Urinary incontinence in women, without manifest injury to the bladder. Surgery, Gynecology and Obstetrics. 1914;18:444-450.

Lagro-Janssen T, van Weel C. Long term effect of treatment of female incontinence in general practice. British Journal of General Practice. 1998;48:1735-1738.

Lara C, Nacey J. Ethnic differences between Maori, Pacific Island and European New Zealand women in prevalenceand attitudes to urinary incontinence. New Zealand Medical Journal. 1994;107:374-376.

Latthe P, Foon R, Toozs-Hobson P. Transobturator and retropubic tape procedures in stress urinary incontinence: a systematic review and a metaanalysis of effectiveness and complications. BJOG: an International Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 2007;114:522-531.

Laycock J, Jerwood D. Pelvic floor assessment: the PERFECT scheme. Physiotherapy. 2001;87:631-642.

Leboeuf L, Tellez CA, Ead D, Gousse AE. Complication of bowel injury perforation during insertion of tension-free vaginal tape. Journal of Urology. 2003;170:1310.

Mariappan P, Alhasso A, Ballantyne Z, Grant A, N’Dow J. Duloxetine, a serotonin and noradrenaline reuptake inhibitor (SNRI) for the treatment of stress urinary incontinence: a systematic review. European Urology. 2007;51:67-74.

Marshall V, Marchetti A, Krantz K. The correction of stress incontinence by simple vesicourethral suspension. Surgery, Gynecology and Obstetrics. 1949;88:509-518.

Miller L, Lose G, Jorgensen T. The prevalence and bothersomeness of lower urinary tract symptoms in women 40–60 years of age. Acta Obstetricia et Gynecologica Scandinavica. 2000;79:298-305.

Nakanishi N, Tatara K, Naramura H, Fujiwara H, Takashima Y, Fukuda H. Urinary and faecal incontinence in a community-residing older population in Japan. Journal of the American Geriatric Society. 1997;45:215-219.

Nation E. Howard Atwood Kelly (1858–1943). Journal of Pelvic Surgery. 1997;3:71-74.

Nelson R, Furner S, Jesudason V. Urinary incontinence in Wisconsin skilled nursing facility: prevalence and associations in common with fecal incontinence. Journal of Aging and Health. 2001;13:539-547.

National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. Urinary Incontinence: the Management of Urinary Incontinence in Women. London: NICE; 2006. Available at http://www.nice.org.uk/CG040/

Nygaard I, Lemke J. Urinary incontinence in rural older women; prevalence, incidence and remission. Journal of the American Geriatric Society. 1996;44:1049-1054.

Nygaard I, Zmolek G. Exercise pad testing in continent exercisers: reproducibility and correlation with voided volume, pyridium staining and type of excercise. Neurourology and Urodynamics. 1995;14:125-129.

Petros P, Ulmstem U. An integral theory and its method for the diagnosis and management of female urinary incontinence. Scandinavian Journal of Urology and Nephrology. 1993;153:1-93.

Radley SC, Jones GL, Tanguy EA, Stevens VG, Nelson C, Mathers NJ. Computer interviewing in urogynaecology: concept, development and psychometric testing of an electronic pelvic floor assessment questionnaire (ePAQ) in primary and secondary care. BJOG: an International Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 2006;113:231-238.

Reid F, Smith A, Dunn G. Which questionnaire? A psychometric evaluation of three patient-based outcome measures used to assess surgery for stress urinary incontinence. Neurourology and Urodynamics. 2007;26:123-128.

Rekers H, Drogendijk AC, Valkenburg H, Riphagen F. Urinary incontinence in women 35 to 79 years of age: prevalence and consequences. European Journal of Obstetrics, Gynecology and Reproductive Biology. 1992;43:229-234.

Resnick N. Geriatric incontinence. Urologic Clinics of North America. 1996;23:55-74.

Rortveit G, Daltveit AK, Hannestad YS, Hunskaar S, Norwegian EPINCONT Study. Urinary incontinence after vaginal delivery or cesarean section. New England Journal of Medicine. 2003;348:900-907.

Samuelson E, Victor F, Svardsudd K. Five year incidence and remission rates of female urinary incontinence in Swedish population less than 65 years old. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2000;183:568-574.

Sandvik H, Espuna M, Hunskaar S. Validity of incontinence severity index: comparison with pad-weighing tests. International Urogynecology Journal and Pelvic Floor Dysfunction. 2006;17:520-524.

Shaikh S, Ong EK, Glavind K, Cook J, N’Dow JM 2006 Mechanical devices for urinary incontinence in women. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 3: CD001756.

Simons AM, Yoong WC, Buckland S, Moore KH. Inadequate repeatability of the one hour pad test; the need for a new incontinence outcome measure. BJOG: an International Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 2001;108:315-319.

Sinha D, Nallaswamy V, Arunkalaivanan A. Value of leak point pressure study in women with incontinence. Journal of Urology. 2006;176:186-188.

Smith A, et al. Surgery for urinary incontinence in women. International Consultation on Incontinence, 2008. Plymouth, MA: Health Publication Ltd; 2009.

Spence-Jones C, Kamm MA, Henry MM, Hudson CN. Bowel dysfunction: a pathogenic factor in uterovaginal prolapse and urinary stress incontinence. BJOG: an International Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 1994;101:147-152.

Subak LL, Johnson C, Whitcomb E, et al. Does weight loss improve incontinence in moderately obese women? International Urogynecology Journal and Pelvic Floor Dysfunction. 2002;13(1):40-43.

Sung VW, Schleinitz MD, Rardin CR, Ward RM, Myers DL. Comparison of retropubic vs transobturator approach to midurethral slings: a sytematic review and meta-analysis. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2007;197:3-11.

Swithinbank LV, Donovan JL, du Heaume JC, et al. Urinary symptoms and incontinence in women: relationship between occurrence, age and perceived impact. British Journal of General Practice. 1999;49:897-900.

Thom DH, Van Den Eeden SK, Ragins AI, et al. Differences in prevalence of urinary incontinence by race/ethnicity 6. Journal of Urology. 2006;175:259-264.

Thomas TM, Plymat KR, Blannin J, Meade TW. Prevalence of urinary incontinence. BMJ (Clinical Research Ed.). 1980;281:1243-1245.

Ulmsten U, Henriksson L, Johnson P, Varhos G. An ambulatory surgical procedure under local anesthesia for treatment of female urinary incontinence. International Urogynecology Journal and Pelvic Floor Dysfunction. 1996;7:81-85.

van Oyen H, van Oyen P. Urinary incontinence in Belgium; prevalence, correlates and psychological consequences. Acta Clinica Belgica. 2002;57:207-218.

Vancaillie T, Schuessler W. Laparoscopic bladderneck suspension. Journal of Laparoendoscopic Surgery. 1991;1:169-173.

Vella M, Dukkett J, Basu M. Duloxetine 1 year on: the long term outcome of women prescribed duloxetine. International Urogynecology Journal and Pelvic Floor Dysfunction. 2008;19:961-964.

Viktrup L, Lose G. The risk of stress incontinence 5 years after first delivery. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2001;185:82-87.

Ward K, Hilton P. Prospective multicentre randomised trial of tension free vaginal tape and colposuspension as primary treament for stress incontinence. BMJ (Clinical Research Ed.). 2002;325:67-70.

Wetle T, Scherr P, Branch LG, et al. Difficulty with holding urine among older persons in a geographically defined community: prevalence and correlates. Journal of the American Geriatric Society. 1995;43:349-355.

Yarnell JW, Voyle GJ, Richards CJ, Stephenson TP. The prevalence and severity of urinary incontinence in women. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health. 1981;35:71-74.