3 Upper Extremity Block Anatomy

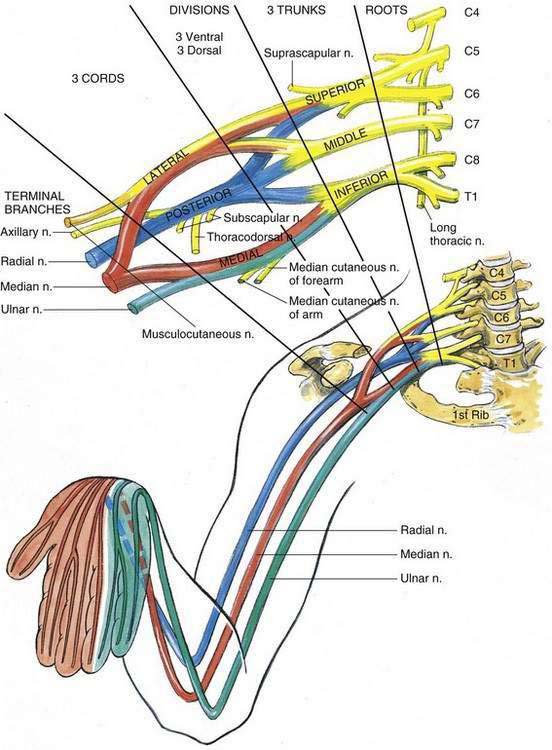

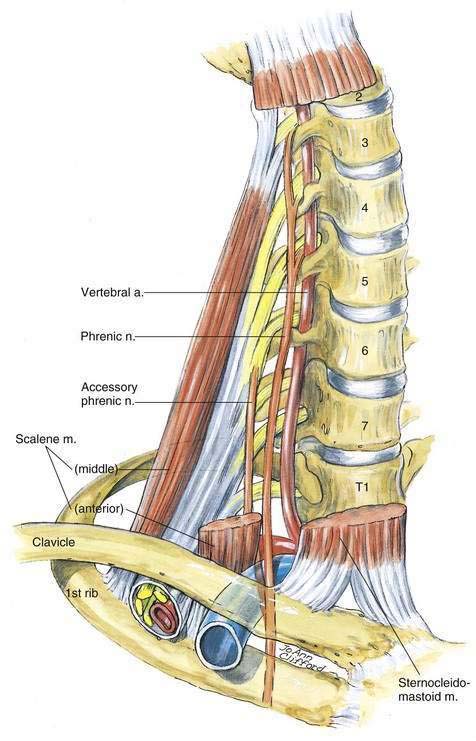

Figure 3-1 illustrates that the plexus is formed by the ventral rami of the fifth to eighth cervical nerves and the greater part of the ramus of the first thoracic nerve. In addition, small contributions may be made by the fourth cervical and the second thoracic nerves. The intimidating part of this anatomy is what happens from the time these ventral rami emerge from between the middle and anterior scalene muscles until they end in the four terminal branches to the upper extremity: the musculocutaneous, median, ulnar, and radial nerves. Most of what happens to the roots on their way to becoming peripheral nerves is not clinically essential information for an anesthesiologist. There are some broad concepts that may help clinicians understand the brachial plexus anatomy; throughout, my goal in this chapter is to simplify this anatomy.

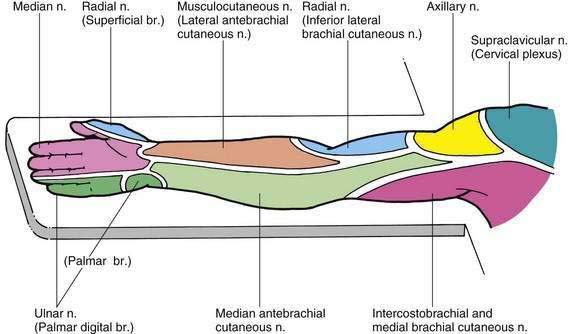

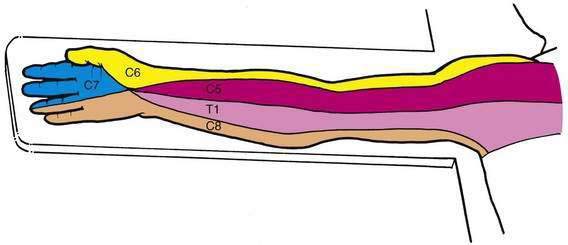

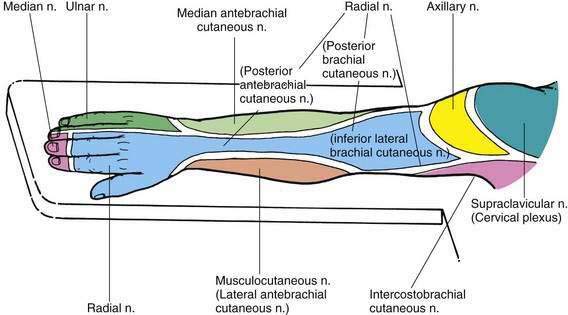

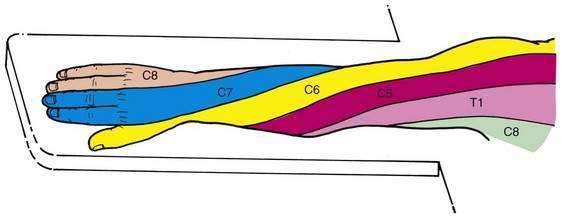

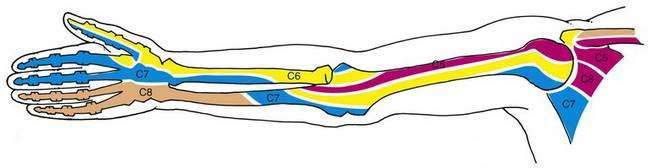

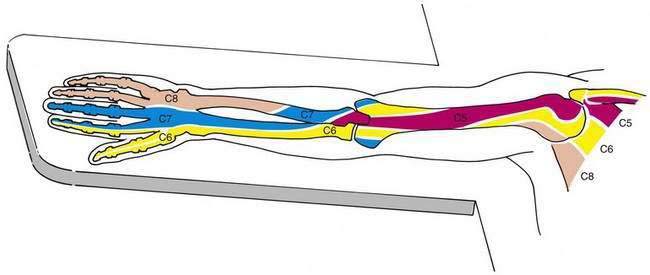

Most upper extremity surgery is performed with the patient resting supine on an operating table with the arm extended on an arm board. Thus, anesthesiologists must understand and clearly visualize the innervation of the upper extremity while the patient is in this position. Figures 3-2 through 3-7 illustrate these features with the arm in the supinated and pronated positions for the cutaneous nerves and dermatomal and osteotomal patterns, respectively.

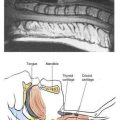

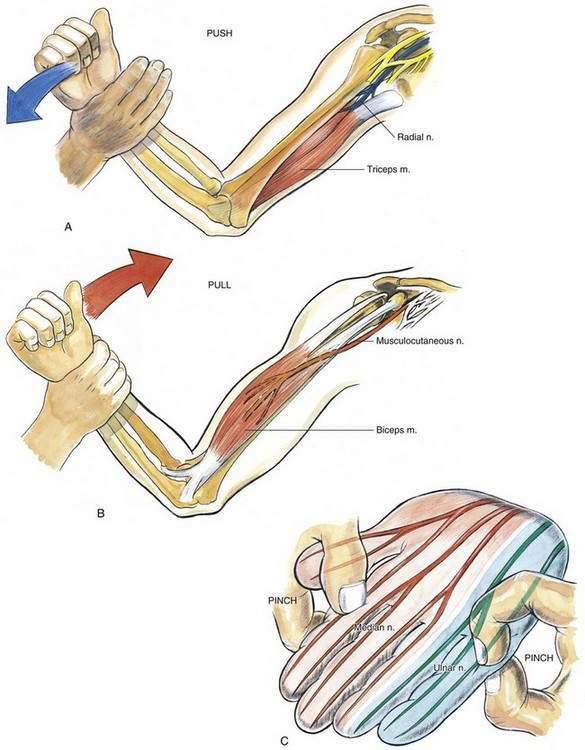

An additional clinical “pearl” that will help anesthesiologists check brachial plexus block before initiation of the surgical procedure is the “four Ps.” Figure 3-8 shows how the mnemonic “push, pull, pinch, pinch” can help an anesthesiologist remember how to check the four peripheral nerves of interest in the brachial plexus block. By having the patient resist the anesthesiologist’s pulling the forearm away from the upper arm, motor innervation to the biceps muscle is assessed. If this muscle has been weakened, one can be certain that local anesthetic has reached the musculocutaneous nerve. Likewise, by asking the patient to attempt to extend the forearm by contracting the triceps muscle, one assesses the radial nerve. Finally, pinching the fingers in the distribution of the ulnar or median nerve—that is, at the base of the fifth or second digit, respectively—helps the anesthesiologist develop a sense of the adequacy of block of both the ulnar and median nerves. Typically, if these maneuvers are performed shortly after brachial plexus block, motor weakness will be evident before sensory block. As a historical highlight, this technique for checking the upper extremity was developed during World War II to allow medics a method of quick analysis of injuries to the brachial plexus.

Figure 3-8. Upper extremity peripheral nerve function mnemonic: “push (A), pull (B), pinch, pinch (C).”

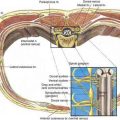

Although some of the brachial plexus neural anatomy of interest to anesthesiologists has been outlined, there are some anatomic details that should be highlighted (Fig. 3-9). As the cervical roots leave the transverse processes on their way to the brachial plexus, they exit in the gutter of the transverse process immediately posterior to the vertebral artery. The vertebral arteries leave the brachiocephalic and subclavian arteries on the right and left, respectively, and travel cephalad, normally entering a bony canal in the transverse process at the level of C6 and above. Thus, one must be constantly aware of needle tip location in relationship to the vertebral artery. It should be remembered that the vertebral artery lies anterior to the roots of the brachial plexus as they leave the cervical vertebrae.

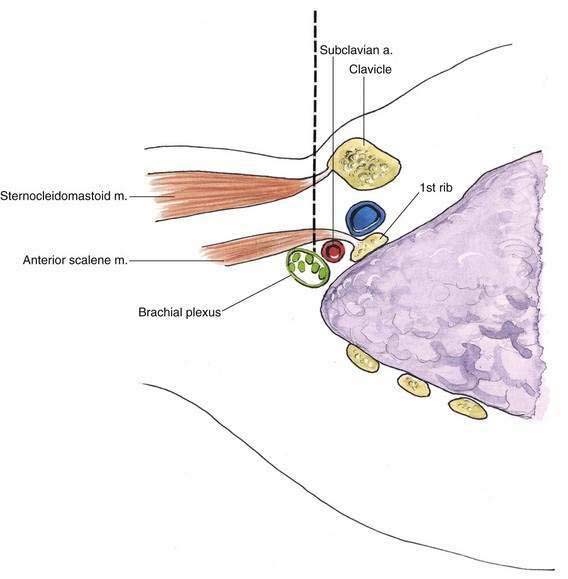

Another detail of the brachial plexus anatomy that needs amplification is the organization of the brachial plexus nerves (divisions) as they cross the first rib. Textbooks often depict the nerves in a stacked arrangement at this point. However, radiologic, clinical, ultrasonographic, and anatomic investigations demonstrate that the nerves are not discretely “stacked” at this point but rather assume a posterior and cranial relationship to the subclavian artery (Fig. 3-10). This is important when one is carrying out supraclavicular nerve block and is using the rib as an anatomic landmark. The relationship of the nerves to the artery means that if one simply walks the needle tip closely along the first rib, one may not as easily elicit paresthesias because the nerves are more cranial in relationship to the first rib.

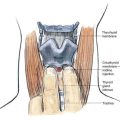

Figure 3-10. Supraclavicular block anatomy: functional anatomy of brachial plexus, subclavian artery, and first rib.

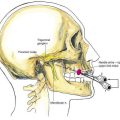

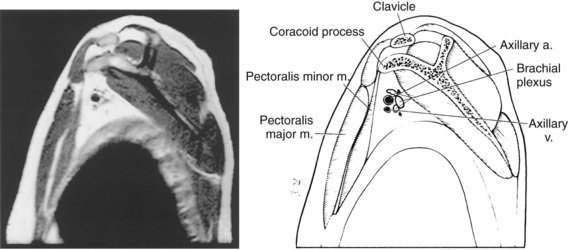

Another anatomic detail needing highlighting is the proximal axillary anatomy at a parasagittal section through the coracoid process. At this transition site, the brachial plexus is changing from the brachial plexus cords to the peripheral nerves as it surrounds the subclavian and axillary arteries (Fig. 3-11). At the site of this parasagittal section the borders of the proximal axilla are formed by the following anatomic structures:

Figure 3-11. Parasagittal magnetic resonance image and line drawing of the important anatomy in the infraclavicular block.

(By permission of the Mayo Foundation, Rochester, Minn.)

These anatomic relationships are important during continuous techniques of infraclavicular block.