Chapter 37 Unknown Head and Neck Primary Site

In a small percentage of patients with squamous cell carcinoma metastatic to the cervical lymph nodes, the primary lesion cannot be found, even after an extensive evaluation. Patients with metastatic adenopathy in the upper neck have a good prognosis when treated aggressively compared with patients with metastatic lymph nodes in the level IV nodes or supraclavicular fossa.1 The latter group is more likely to have a primary lesion located below the clavicles, and the probability of cure is remote. Most patients have either squamous cell carcinoma or poorly differentiated carcinoma. Patients with adenocarcinoma almost always have a primary lesion below the clavicles, although if the nodes are located in the upper neck, one must exclude a salivary gland, thyroid, or parathyroid primary tumor.

This chapter addresses the management of patients presenting with squamous cell or poorly differentiated carcinoma in the upper or middle neck. Squamous cell carcinoma in a parotid area lymph node is almost always metastatic from a cutaneous primary site, and this is not addressed in this chapter.2

Diagnostic Evaluation

Patients should be evaluated with a thorough physical examination including careful evaluation of the head and neck by multiple examiners. A needle biopsy of the lymph node should be performed; fine-needle aspiration is preferred to a biopsy because it is less traumatic, and there is a lower likelihood of seeding tumor cells along the needle track.3–7 Evaluation of the neck node biopsy specimen for Epstein-Barr virus DNA, via polymerase chain reaction, may be useful in detecting a nasopharyngeal primary tumor in geographic areas where this malignancy is prevalent.8 Similarly, evaluation of the biopsy specimen for high-risk human papillomavirus may be useful for detecting an oropharyngeal carcinoma.9 Most occult primary cancers that are detected in the United States are in the oropharynx, however, so, depending on the situation, testing the biopsy specimen for high-risk human papillomavirus may be unlikely to provide additional useful information.10

After chest radiography, computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the head and neck is obtained to detect an unknown primary lesion arising from the mucosa of the head and neck. We use CT initially and follow with MRI only in cases with equivocal findings in which MRI might yield additional useful information. A complete blood count is obtained to evaluate marrow reserve in patients who may be candidates for adjuvant chemotherapy. A chest CT scan should be considered for patents with N3 neck disease and patients with N2B to N2C disease and bulky adenopathy in the low neck to assess the lungs for pulmonary metastases.11 The recommended diagnostic evaluation12 is summarized in Table 37-1.

| General |

From Mendenhall WM, Parsons JT, Mancuso AA, et al: Head and neck: management of the neck. In Perez CA, Brady LW, editors: Principles and practice of radiation oncology, ed 3, Philadelphia, 1998, Lippincott, pp 1135-1156.

Preliminary evidence suggested that 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose single photon emission computed tomography (18F-FDG-SPECT) or 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography (18F-FDG-PET) scans may identify primary lesions that would not otherwise be identifiable.13,14 Theoretically, tumor cells have a higher metabolic rate than normal tissues and take up more FDG so that they appear “hot” on a PET or SPECT scan. If 18F-FDG-SPECT or 18F-FDG-PET scan is obtained as part of the work-up, it should be performed before panendoscopy so that any suspicious areas of increased uptake can be biopsied. Limited data pertaining to the usefulness of 18F-FDG-SPECT and 18F-FDG-PET scans suggest these procedures may identify the primary site in a relatively small subset of patients.15–17 18F-FDG-SPECT scan correctly identified the occult primary site in only 1 of 26 patients (4%) at our institution10 (Table 37-2). Similarly, 18F-FDG-PET detected a primary site in none of 21 patients at the University of Florida10 (Table 37-3). At the present time, 18F-FDG-PET scans are not routinely obtained at our institution as part of the diagnostic evaluation of these patients.

TABLE 37-2 Detection of the Primary Site on 18F-Fluorodeoxyglucose Single-Photon Emission Computed Tomography (18FDG-SPECT)

| Patient Group | 18FDG-SPECT Negative* | 18FDG-SPECT Positive* |

|---|---|---|

| PE− and/or Radiol− | No data | 1/5 |

| PE+ and/or Radiol+ | 2/6 | 6/15 (40.0%) |

| Total | 2/6 | 7/20 (35.0%) |

PE, physical examination; Radiol, radiologic examination (CT and/or MRI); −, negative; +, suspicious, but not definitely positive.

* Number of primaries detected/number of patients.

From Cianchetti M, Mancuso AA, Amdur R, et al: Diagnostic evaluation of squamous cell carcinoma metastatic to cervical lymph nodes from an unknown head and neck primary site, Laryngoscope 119:2348-2354, 2009.

TABLE 37-3 Detection of the Primary Site by 18F-Fluorodeoxyglucose Positron Emission Tomography (18FDG-PET) or 18F-Fluorodeoxyglucose Positron Emission Tomography and Computed Tomography (18FDG-PET/CT)

| Patient Group | 18FDG-PET Negative* | 18FDG-PET Positive* |

|---|---|---|

| PE− and/or Radiol− | 3/4 | No data |

| PE+ and/or Radiol+ | 8/12 | 3/5 |

| Total | 11/16 (68.8%) | 3/5 (60%) |

PE, physical examination; Radiol, radiologic examination (CT and/or MRI); −, negative; +, suspicious, but not definitely positive.

* Number of primaries detected/number of patients.

From Cianchetti M, Mancuso AA, Amdur R, et al: Diagnostic evaluation of squamous cell carcinoma metastatic to cervical lymph nodes from an unknown head and neck primary site, Laryngoscope 119:2348-2354, 2009.

Direct laryngoscopy with fiberoptic endoscopic visualization under general anesthesia is performed with directed biopsies of the nasopharynx, tonsils, base of tongue, and piriform sinuses and of any abnormalities noted on CT or MRI or suspicious mucosal lesions observed during endoscopy. The primary tumor site is discovered at direct laryngoscopy in a subset of patients. The likelihood of discovering the primary site is related to whether or not a suspected (but not definite) primary site is discovered on physical examination or radiographic evaluation10 (Table 37-4). Most suspected primary sites are detected by pretreatment radiographic workup as opposed to physical examination.

TABLE 37-4 Detection of a Primary Site versus Patient Group

| Patient Group | No. Patients with Pathologically Proven Site in Tonsillar Fossa/ No. Patients Having Tonsillectomy |

|---|---|

| PE− and/or Radiol− | 21/72 (29.2%) |

| PE− and/or Radiol+ | 51/82 (62.2%) |

| PE+ and/or Radiol− | 15/25 (60.0%) |

| PE+ and/or Radiol+ | 39/57 (68.4%) |

| TOTAL | 126/236 (53.4%) |

PE, physical examination; Radiol, radiologic examination (CT and/or MRI); −, negative; +, suspicious, but not definitely positive.

From Cianchetti M, Mancuso AA, Amdur R, et al: Diagnostic evaluation of squamous cell carcinoma metastatic to cervical lymph nodes from an unknown head and neck primary site, Laryngoscope 119:2348-2354, 2009.

An ipsilateral10,15,18 tonsillectomy should be performed in patients who have not had a prior tonsillectomy and who have adequate lymphoid tissue remaining in the tonsillar fossa. Although some authors recommend a bilateral tonsillectomy,19 the likelihood of finding the primary site in the contralateral tonsil for patients with ipsilateral neck nodes is probably quite low. Lapeyre and colleagues18 reported 87 patients who were evaluated during the period 1969-1992 and underwent a unilateral tonsillectomy; 26% of patients were found to have a tonsillar cancer. At the University of Florida, 79 of 236 patients underwent a tonsillectomy at the time of direct laryngoscopy; the primary site was detected in the tonsil in 35 patients (44%).10 The likelihood of detecting the primary site was related to whether there were suspicious findings on physical examination or radiographic evaluation10 (Table 37-5).

TABLE 37-5 Detection of the Primary Site on Tonsillectomy

| Patient Group | No. Patients with Pathologically Proven Site in Tonsillar Fossa/ No. Patients Having Tonsillectomy |

|---|---|

| PE− and/or Radiol− | 9/22 (41.1%) |

| PE+ and/or Radiol+ | 26/57 (45.6%) |

| Total | 35/79 (44.3%) |

PE, physical examination; Radiol, radiologic examination (CT and/or MRI); −, negative; +, suspicious, but not definitely positive.

From Cianchetti M, Mancuso AA, Amdur R, et al: Diagnostic evaluation of squamous cell carcinoma metastatic to cervical lymph nodes from an unknown head and neck primary site, Laryngoscope 119:2348-2354, 2009.

Primary head and neck cancers were found in 126 of 236 patients (53%) in the University of Florida series.10 The most common primary sites were tonsillar fossa (59 patients [45%]) and base of tongue (58 patients [44%]).10 The reason for the decreased likelihood of detecting cancers in other sites may be that they are found on physical examination with fiberoptic endoscopy and on radiographic evaluation.7,20,21 In contrast, it is still very difficult to discern a small primary cancer hidden in the lymphoid tissue of the tonsillar fossa or tongue base.

Primary Therapy and Results

Treatment Techniques and Algorithm

Treatment options range from treatment of the involved neck alone with a neck dissection, radiotherapy, or both to irradiation of the suspected primary site and both sides of the neck followed by evaluation for a planned neck dissection.22–24 Although treatment of the potential mucosal primary site and contralateral neck seems to reduce the risk of a locoregional recurrence, the impact on survival is modest at best. Patients with a single positive node without extracapsular extension may be treated with a neck dissection alone and followed closely, provided that the neck was not violated with an open procedure before surgery.25–27

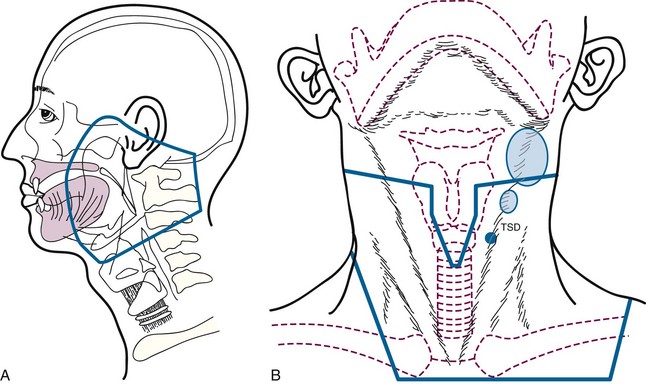

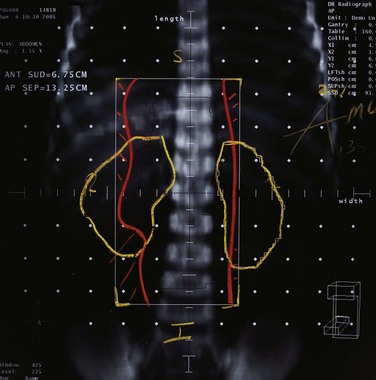

If radiotherapy is indicated to treat the involved neck, we usually irradiate the nasopharynx and oropharynx in addition to both sides of the neck1 (Fig. 37-1A). Although it may be tempting to irradiate the involved neck alone or combined with radiotherapy to the ipsilateral mucosal sites deemed to be at risk, the base of tongue is a midline structure that probably harbors the undetected primary site as often as the tonsillar fossa, so it has been our policy to treat the entire oropharynx.28 Failure to do so is likely associated with an increased risk of a locoregional recurrence, and further radiotherapy would be complicated by the initial treatment.29 Irradiation of the oral cavity is unnecessary, unless the patient has submandibular adenopathy, in which case we either do a neck dissection and observe the patient or irradiate the oral cavity and oropharynx. Previously, it was our policy to irradiate the larynx and hypopharynx, but because the likelihood of a primary tumor in these sites is low and because the morbidity of irradiating these areas is significant, we modified our technique several years ago.28 It could be argued that the nasopharynx should also be eliminated from the primary treatment portals. However, the incidence of positive retropharyngeal nodes is relatively high in patients presenting with advanced neck disease30 so that the portals must include the skull base (jugular foramen and retropharyngeal nodes) and at least part of the nasopharynx. We believe that a modest increase in the size of the portals to irradiate the nasopharynx adequately does not significantly increase morbidity.

Patients are treated with parallel-opposed fields at 1.8 Gy per fraction to a midline dose of 64.8 Gy to the mucosal sites with reduction off the spinal cord at 45 Gy tumor dose31 (Fig. 37-1B). The lower neck is treated through a separate en face anterior field. Lymph nodes in levels IB through V are irradiated on the involved side and in levels II through IV on the clinically negative side. Treatment is administered with cobalt-60 (60Co), 4 MV x rays, or 6 MV x rays. Dosimetry is obtained at the level of the central axis (which usually corresponds to the oropharynx) and the nasopharynx. The dose to the nasopharynx is usually 3 to 5 Gy lower than the central axis. Patients with ipsilateral nodes may be treated with intensity-modulated radiotherapy to decrease the dose to the contralateral parotid (≤26 Gy mean dose) to reduce the likelihood of long-term xerostomia. Patients with bilateral-positive nodes are better treated with parallel-opposed fields to reduce the risk of a marginal miss.32 Positive nodes are boosted to the involved part of the neck using anteroposterior wedged beams to a total dose in the range of 70 to 75 Gy. Concomitant chemotherapy should be considered for patients with advanced N2 and N3 neck disease. We use weekly cisplatin at 30 mg/m2 or cisplatin at 100 mg/m2 every 3 weeks for two cycles.33

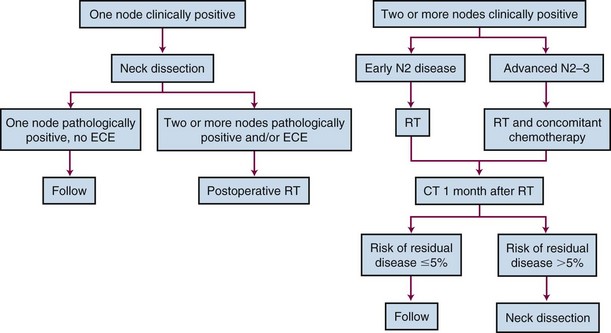

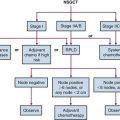

Treatment of the neck depends on the extent and location of the adenopathy. Patients with N1 and early N2B neck disease located in the high-dose fields may be treated with irradiation alone if the nodes have resolved completely.34–36 Similarly, if the patient has undergone an excisional biopsy of a single positive node, the neck may be treated with radiation alone with a 95% likelihood of neck control.37 Patients undergo a CT scan of the neck 1 month after completing radiotherapy at our institution, and the decision whether to proceed with neck dissection depends on the likelihood that viable tumor remains in the neck.38–40 The criteria employed for determining whether a neck dissection38,40 should be performed are outlined in Table 37-6. Because the likelihood of cure is low if a regional recurrence develops in a clinically positive neck after treatment with radiotherapy alone, we usually proceed with a modified neck dissection if the risk of residual disease exceeds 5%.41 In practice, patients with N2-N3 neck disease and patients with gross neck disease after an open neck biopsy often undergo a planned neck dissection after radiotherapy.36,42 The treatment algorithm is depicted in Figure 37-2.

TABLE 37-6 Predictive Value of Postradiotherapy Computed Tomography Findings at 4 Weeks in the Hemineck Correlated to Neck Dissection Pathology*

| Finding | NPV, No./Total No. | PPV, No./Total No. |

|---|---|---|

| Any lymph node >1.5 cm | 85/118 (72%) | 24/75 (32%) |

| Any focally abnormal lymph node† | 49/57 (86%) | 49/136 (36%) |

| Any lymph node with focal lucency | 75/98 (77%) | 34/95 (36%) |

| Any lymph node enhancement | 111/147 (76%) | 21/46 (46%) |

| Any lymph node with calcification | 102/144 (71%) | 15/49 (31%) |

| Two or more focally abnormal lymph nodes† | 90/113 (80%) | 34/80 (43%) |

| Any lymph node >1.5 cm and any focally abnormal lymph node | 32/34 (94%) | 55/159 (35%) |

NPV, negative predictive value; PPV, positive predictive value.

† Focally abnormal lymph node—grade 3 to 4 focal lucency, focal enhancement, or focal calcification.

From Liauw SL, Mancuso AA, Amdur RJ, et al: Postradiotherapy neck dissection for lymph node-positive head and neck cancer: the use of computed tomography to manage the neck, J Clin Oncol 24:1421-1427, 2006.

Results

During the period 1968-1992, 136 patients were treated at the M.D. Anderson Hospital and had a median duration of follow-up of 8.7 years.43 Both sides of the neck and potential head and neck mucosal primary sites were irradiated. A mucosal head and neck cancer developed in 14 patients (10%); 6 of the 14 cancers were located in unirradiated sites. Recurrent disease in the neck developed in 12 patients (9%). The 5-year cause-specific survival rate was 74%.

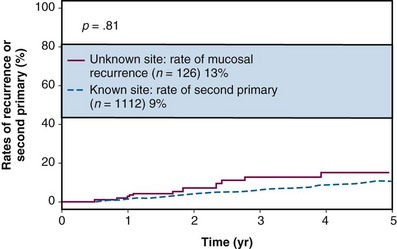

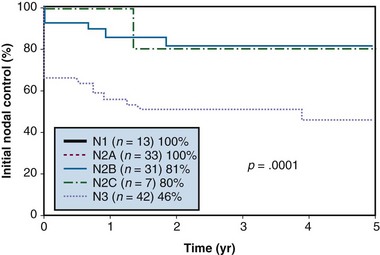

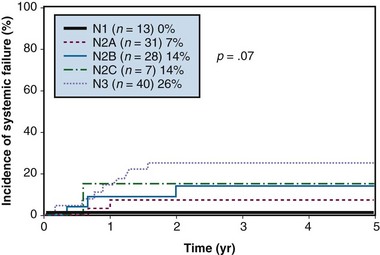

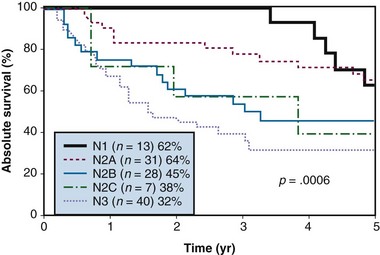

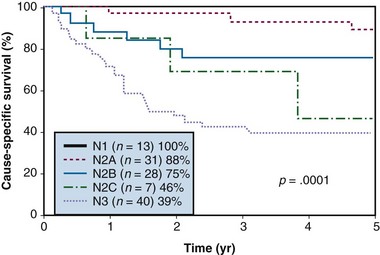

The incidence of subsequent mucosal primary lesions was compared by Erkal and associates44 for patients with a known primary site and a series of 126 patients treated for an unknown primary site at the University of Florida. The incidence for both groups was similar at 5 years, suggesting either that mucosal irradiation significantly reduced the risk of primary site failure or that patients with unknown primary sites have a much lower risk of a second primary head and neck cancer developing subsequently44 (Fig. 37-3). The 5-year absolute and cause-specific survival rates for the 126 patients with an unknown primary were 47% and 67%. The 5-year outcomes stratified by stage44 are shown in Figures 37-4 through 37-7.

Figure 37-4 Nodal control rates according to N category after initial treatment.

From Erkal HS, Mendenhall WM, Amdur RJ, et al: Squamous cell carcinomas metastatic to cervical lymph nodes from an unknown head-and-neck mucosal site treated with radiation therapy alone or in combination with neck dissection, Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 50:55-63, 2001.

Figure 37-5 Systemic failure (distant metastases) according to N category after treatment.

From Erkal HS, Mendenhall WM, Amdur RJ, et al: Squamous cell carcinomas metastatic to cervical lymph nodes from an unknown head-and-neck mucosal site treated with radiation therapy alone or in combination with neck dissection, Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 50:55-63, 2001.

Figure 37-6 Absolute survival according to N category after treatment.

From Erkal HS, Mendenhall WM, Amdur RJ, et al: Squamous cell carcinomas metastatic to cervical lymph nodes from an unknown head-and-neck mucosal site treated with radiation therapy alone or in combination with neck dissection, Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 50:55-63, 2001.

Figure 37-7 Cause-specific survival according to N category after treatment.

From Erkal HS, Mendenhall WM, Amdur RJ, et al: Squamous cell carcinomas metastatic to cervical lymph nodes from an unknown head-and-neck mucosal site treated with radiation therapy alone or in combination with neck dissection, Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 50:55-63, 2001.

Reddy and Marks29 reported 52 patients treated to the neck alone (16 patients) or to the neck and to potential head and neck mucosal primary sites (36 patients). Failure in the head and neck mucosa occurred in 44% of patients who underwent treatment to the neck alone compared with 8% of patients who underwent irradiation of the head and neck mucosa (p = .0005). The 5-year survival rates were similar for the two treatment groups.

Grau and coworkers45 reported 273 patients treated with curative intent at five cancer centers in Denmark during the period 1975-1995 with surgery alone (23 patients), radiotherapy to the ipsilateral neck alone or combined with surgery (26 patients), and radiotherapy to the neck and head and neck mucosa alone or combined with surgery (224 patients). The ipsilateral oropharynx unintentionally received some irradiation in patients treated to the ipsilateral neck alone, depending on the treatment technique.45 The 5-year rates of freedom from failure in the head and neck mucosa were as follows: surgery alone, 45%; radiotherapy with or without surgery to the ipsilateral neck, 77%; and radiotherapy to the head and neck mucosa with or without surgery, 87%. Failure in the oropharynx, particularly the base of tongue, was the most common location of mucosal site failure.

Complications

The main complication of radiotherapy for patients treated for an unknown head and neck primary tumor is xerostomia. Intensity-modulated radiotherapy may be used to reduce the dose to the contralateral parotid gland as long as the patient does not have bilateral clinically positive neck nodes. It is difficult to limit the dose to the parotid if there are positive nodes in the same side of the neck without risking underdosing the adenopathy and increasing the risk of a marginal miss.32 Additional complications may include fibrosis and limited range of motion. The risk of bone exposure, radiation myelitis, or radiation-induced malignancy is very low.

The incidence of postoperative complications in a University of Florida series of 143 patients treated with radiation to the primary lesion and neck followed by unilateral neck dissection was 23%.36 Of patients, 17 (12%) required a second operation, and 4 (3%) experienced fatal complications. The incidence of complications was higher for maximum subcutaneous doses greater than 60 Gy. Taylor and associates46 updated the University of Florida experience with an analysis of the incidence of moderate (2+) and severe (3+) wound complications in a series of 205 patients who underwent a planned unilateral neck dissection after irradiation. Radiotherapy was given once daily in 123 patients, twice daily in 80 patients, and with both once-daily and twice-daily techniques in the remaining 2 patients. The incidence of wound complications tended to increase with total dose and dose per fraction.

1 Mendenhall WM, Mancuso AA, Amdur RJ, et al. Squamous cell carcinoma metastatic to the neck from an unknown head and neck primary site. Am J Otolaryngol. 2001;22:261-267.

2 Hinerman RW, Amdur RJ, Morris CG, et al. Cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma metastatic to parotid-area lymph nodes. Laryngoscope. 2008;118:1989-1996.

3 McGuirt WF, McCabe BF. Significance of node biopsy before definitive treatment of cervical metastatic carcinoma. Laryngoscope. 1978;88:594-597.

4 Parsons JT, Million RR, Cassisi NJ. The influence of excisional or incisional biopsy of metastatic neck nodes on the management of head and neck cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1985;11:1447-1454.

5 Ellis ER, Mendenhall WM, Rao PV, et al. Incisional or excisional neck-node biopsy before definitive radiotherapy, alone or followed by neck dissection. Head Neck. 1991;13:177-183.

6 Robbins KT, Cole R, Marvel J, et al. The violated neck: Cervical node biopsy prior to definitive treatment. Otolaryngol Clin North Am. 1986;94:605-610.

7 Martin H, Morfit HM. Cervical lymph node metastasis as the first symptom of cancer. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1944;76:133-159.

8 Macdonald MR, Freeman JL, Hui MF, et al. Role of Epstein-Barr virus in fine-needle aspirates of metastatic neck nodes in the diagnosis of nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Head Neck. 1995;17:487-493.

9 Begum S, Gillison ML, Nicol TL, et al. Detection of human papillomavirus-16 in fine-needle aspirates to determine tumor origin in patients with metastatic squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13:1186-1191.

10 Cianchetti M, Mancuso AA, Amdur R, et al. Diagnostic evaluation of squamous cell carcinoma metastatic to cervical lymph nodes from an unknown head and neck primary site. Laryngoscope. 2009;119:2348-2354.

11 Al-Othman MOF, Morris CG, Hinerman RW, et al. Distant metastases after definitive radiotherapy for squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck. Head Neck. 2003;25:629-633.

12 Mendenhall WM, Parsons JT, Mancuso AA, et al. Principles and practice of radiation oncology. Philadelphia: Lippincott-Raven; 1998.

13 Mukherji SK, Drane WE, Mancuso AA, et al. Occult primary tumors of the head and neck: detection with 2-[F-18] fluoro-2-deoxy-D-glucose SPECT. Radiology. 1996;199:761-766.

14 Johansen J, Buus S, Loft A, et al. Prospective study of 18FDG-PET in the detection and management of patients with lymph node metastases to the neck from an unknown primary tumor: results from the DAHANCA-13 study. Head Neck. 2008;30:471-478.

15 Mendenhall WM, Mancuso AA, Parsons JT, et al. Diagnostic evaluation of squamous cell carcinoma metastatic to cervical lymph nodes from an unknown head and neck primary site. Head Neck. 1998;20:739-744.

16 Greven KM, Keyes JWJr, Williams DWIII, et al. Occult primary tumors of the head and neck: lack of benefit from positron emission tomography imaging with 2-[F-18]Fluoro-2-deoxy-D-glucose. Cancer. 1999;86:114-118.

17 Safa AA, Tran LM, Rege S, et al. The role of positron emission tomography in occult primary head and neck cancers. Cancer J Sci Am. 1999;5:214-218.

18 Lapeyre M, Malissard L, Peiffert D, et al. Cervical lymph node metastasis from an unknown primary: is a tonsillectomy necessary? Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1997;39:291-296.

19 McQuone SJ, Eisele DW, Lee D-J, et al. Occult tonsillar carcinoma in the unknown primary. Laryngoscope. 1998;108:1605-1610.

20 Fletcher GH, Jesse RH, Healey JEJr, et al. Oropharynx. In: MacComb WS, Fletcher GH, editors. Cancer of the Head and Neck. Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins; 1967:179-212.

21 Jones AS, Cook JA, Phillips DE, et al. Squamous carcinoma presenting as an enlarged cervical lymph node. Cancer. 1993;72:1756-1761.

22 Coster JR, Foote RL, Olsen KD, et al. Cervical nodal metastasis of squamous cell carcinoma of unknown origin: indications for withholding radiation therapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1992;23:743-749.

23 Weir L, Keane T, Cummings B, et al. Radiation treatment of cervical lymph node metastases from an unknown primary: an analysis of outcome by treatment volume and other prognostic factors. Radiother Oncol. 1995;35:206-211.

24 Mendenhall WM. Unknown primary squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck. Curr Cancer Ther Rev. 2005;1:167-174.

25 Olsen KD, Caruso M, Foote RL, et al. Primary head and neck cancer: histopathologic predictors of recurrence after neck dissection in patients with lymph node involvement. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1994;120:1370-1374.

26 Huang DT, Johnson CR, Schmidt-Ullrich R, et al. Postoperative radiotherapy in head and neck carcinoma with extracapsular lymph node extension and/or positive resection margins: A comparative study. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1992;23:737-742.

27 Mendenhall WM, Amdur RJ, Hinerman RW, et al. Postoperative radiation therapy for squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck. Am J Otolaryngol. 2003;24:41-50.

28 Barker CA, Morris CG, Mendenhall WM. Larynx-sparing radiotherapy for squamous cell carcinoma from an unknown head and neck primary site. Am J Clin Oncol. 2005;28:445-448.

29 Reddy SP, Marks JE. Metastatic carcinoma in the cervical lymph nodes from an unknown primary site: results of bilateral neck plus mucosal irradiation vs. ipsilateral neck irradiation. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1997;37:797-802.

30 McLaughlin MP, Mendenhall WM, Mancuso AA, et al. Retropharyngeal adenopathy as a predictor of outcome in squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck. Head Neck. 1995;17:190-198.

31 Million RR, Cassisi NJ, Mancuso AA, et al. Management of the neck for squamous cell carcinoma. In: Million RR, Cassisi NJ, editors. Management of Head and Neck Cancer: A Multidisciplinary Approach. Philadelphia: Lippincott; 1994:75-142.

32 Mendenhall WM, Mancuso AA. Radiotherapy for head and neck cancer—is the “next level” down? Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2009;73:645-646.

33 Mendenhall WM, Riggs CE, Amdur RJ, et al. Altered fractionation and/or adjuvant chemotherapy in definitive irradiation of squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck. Laryngoscope. 2003;113:546-551.

34 Peters LJ, Weber RS, Morrison WH, et al. Neck surgery in patients with primary oropharyngeal cancer treated by radiotherapy. Head Neck. 1996;18:552-559.

35 Johnson CR, Silverman LN, Clay LB, et al. Radiotherapeutic management of bulky cervical lymphadenopathy in squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck: is postradiotherapy neck dissection necessary? Radiat Oncol Invest. 1998;6:52-57.

36 Mendenhall WM, Million RR, Cassisi NJ. Squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck treated with radiation therapy: the role of neck dissection for clinically positive neck nodes. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1986;12:733-740.

37 Mack Y, Parsons JT, Mendenhall WM, et al. Squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck: Management after excisional biopsy of a solitary metastatic neck node. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1993;25:619-622.

38 Ojiri H, Mancuso AA, Mendenhall WM, et al. Lymph nodes of patients with regional metastases from head and neck squamous cell carcinoma as a predictor of pathologic outcome: size changes at CT before and after radiation therapy. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2002;23:1012-1018.

39 Yeung AR, Liauw SL, Amdur RJ, et al. Lymph node-positive head and neck cancer treated with definitive radiotherapy: can treatment response determine the extent of neck dissection? Cancer. 2008;112:1076-1082.

40 Liauw SL, Mancuso AA, Amdur RJ, et al. Postradiotherapy neck dissection for lymph node-positive head and neck cancer: the use of computed tomography to manage the neck. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:1421-1427.

41 Mendenhall WM, Villaret DB, Amdur RJ, et al. Planned neck dissection after definitive radiotherapy for squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck. Head Neck. 2002;24:1012-1018.

42 Brizel DM, Prosnitz RG, Hunter S, et al. Necessity for adjuvant neck dissection is setting of concurrent chemoradiation for advanced head-and-neck cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2004;58:1418-1423.

43 Colletier PJ, Garden AS, Morrison WH, et al. Postoperative radiation for squamous cell carcinoma metastatic to cervical lymph nodes from an unknown primary site: outcomes and patterns of failure. Head Neck. 1998;20:674-681.

44 Erkal HS, Mendenhall WM, Amdur RJ, et al. Squamous cell carcinomas metastatic to cervical lymph nodes from an unknown head-and-neck mucosal site treated with radiation therapy alone or in combination with neck dissection. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2001;50:55-63.

45 Grau C, Johansen LV, Jakobsen J, et al. Cervical lymph node metastases from unknown primary tumours: results from a national survey by the Danish Society for Head and Neck Oncology. Radiother Oncol. 2000;55:121-129.

46 Taylor JMG, Mendenhall WM, Parsons JT, et al. The influence of dose and time on wound complications following post-radiation neck dissection. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1992;23:41-46.