Ultrasound-guided placement of peripherally inserted central venous catheters

Overview

At the beginning of this century, the widespread use of ultrasound for guiding vascular access has dramatically changed the technique of insertion of PICCs.1–6 Currently, PICCs are inserted by ultrasound-guided puncture and cannulation of the deep upper arm veins (most often the basilic or brachial vein) via the modified Seldinger technique (venipuncture with a small-gauge needle, insertion of a thin guidewire through the needle, removal of the needle, insertion of a microintroducer-dilator over the guidewire, removal of the wire and dilator, insertion of the catheter through the introducer). This technique facilitates catheterization of large-bore veins of known diameter and trajectory while allowing positioning of the exit site in the upper part of the arm (halfway between the elbow and the axilla). As a final result, the rate of insertion failure is minimal, insertion-related complications are almost negligible, the exit site is handled easily by patients and nursing stuff (easy dressing and securement, good patient comfort), and the rate of late complications (infection, catheter-related venous thrombosis, dislocation) is low.

Ultrasound anatomy of the arm veins

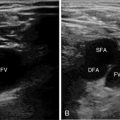

PICCs are usually inserted in the deep veins of the arm, which allows an exit site in the middle third of the upper part of the arm. Sometimes the only veins available for cannulation (in terms of diameter) are quite close to the axilla. In such cases the catheter can be tunneled downward to obtain a more favorable exit site. The deep veins of the forearm should not be considered for PICC insertion; however, these veins can be used for ultrasound-guided insertion of peripheral lines. The most frequently accessed vein is the basilic vein, which runs in the groove between the humerus and the biceps muscle. This vein usually has a large diameter (4 to 6 mm) and is located rather superficially (10 to 25 mm from the surface of the skin) and relatively distant from arteries and major nerves. The brachial veins are an alternative option. Their number may range between two and four, and they generally travel close to the brachial artery and the median nerve (which is typically located adjacent to the artery; see Chapter 51). The brachial veins are smaller (with diameters ranging from 1 to 4 mm) and usually travel medially and deeper than the basilic vein; however, anatomic variations are numerous. When visualized sonographically in a transverse plane, the artery and the two adjacent basilic veins appear to have a “Mickey Mouse”–like configuration. Because of their diameter and proximity to structures such as the brachial artery and the median nerve, the basilic veins are not a primary option for catheterization.

Sonographic visualization of all arm veins in a transverse plane is relatively easy and facilitates a “panoramic” view of all adjacent anatomic structures (e.g., nerves, arteries, muscles) in a region of interest (ROI). The importance of this “panoramic” view is analyzed elsewhere according to the holistic approach ultrasound concept (Chapters 1 and 51). When transducer compression is applied to an ROI, a vessel that pulsates is an artery, whereas a vessel that does not pulsate and is noncollapsible is most likely a thrombosed vein (Chapter 9).

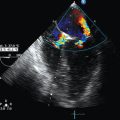

Since PICCs are “central” lines, their tip should be positioned adjacent to the cavoatrial junction.7 A gross preprocedural evaluation of the length of catheter that ensures correct tip positioning can be performed by empiric methods (distance from the exit site to the midclavicular point plus the distance from the midclavicular point to the third intercostal space on the right parasternal line). Appropriate verification of tip position should be obtained intraprocedurally (fluoroscopy or intracavitary electrocardiography) or postprocedurally (chest radiography or echocardiography).

The safe insertion protocol for peripherally inserted central catheters

Safe PICC insertion depends on many factors: successful puncture and cannulation of the vein via a real-time ultrasound-guided aseptic technique, appropriate positioning of the tip of the catheter, and securement of the catheter at the exit site. Therefore the key to uneventful insertion and successful clinical performance of the device is the adoption of evidence-based, cost-effective strategies to minimize the incidence of complications. The GAVeCeLT (Italian Group for Central Venous Access) has developed a set of recommendations that summarize the most important steps for insertion of PICCs based on current international guidelines.7–13 This set of recommendations (the safe insertion of PICCs [SIP] protocol) includes eight steps:

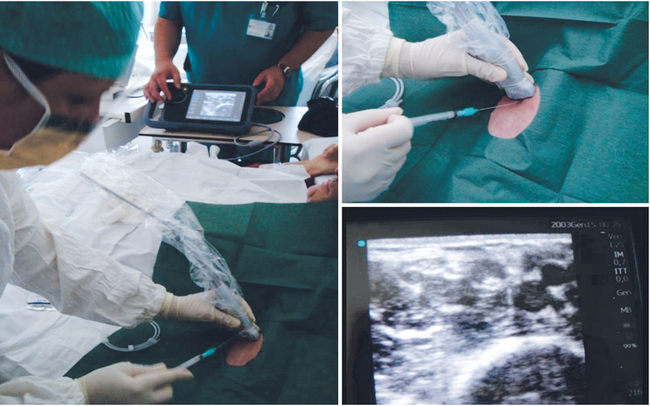

1. Hand washing, aseptic technique, and maximal barrier protection. According to the international guidelines,12,13 “maximal barrier protection” includes sterile gloves, nonsterile mask, nonsterile hat, sterile gown, and a vast body drape over the patient. Chlorhexidine 2% in an alcohol solution (70% isopropyl alcohol) should be preferred for skin preparation before PICC insertion.

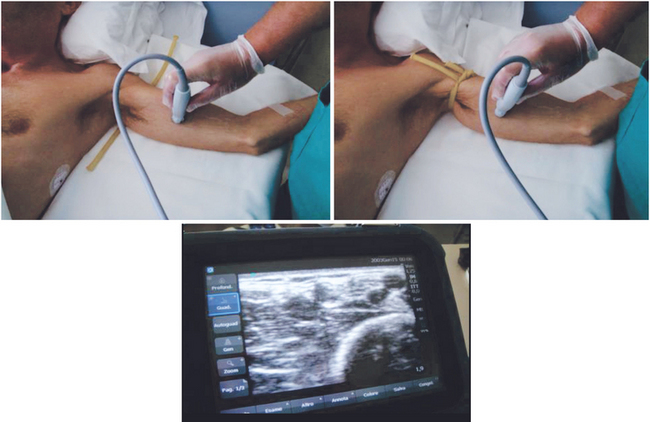

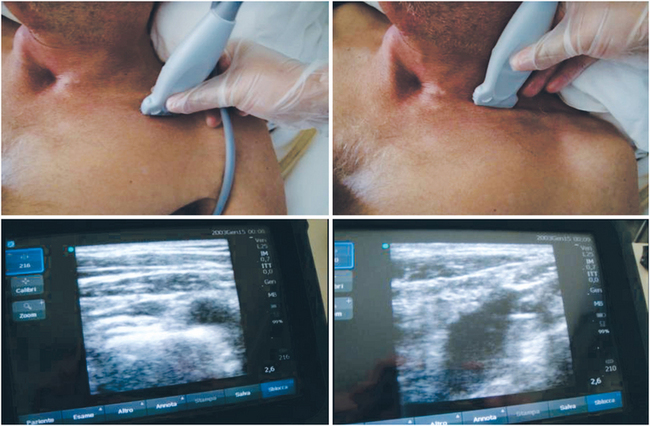

2. Bilateral ultrasound scans of all neck and arm veins. Preprocedural bilateral scans of the deepest arm veins (basilic, brachial; Figure 15-1) and neck veins (axillary, subclavian, internal jugular, brachiocephalic; Figure 15-2) should be performed. Such scanning is essential to rule out major vascular and other pertinent anatomic abnormalities or variations and preexisting venous thrombosis and thus facilitate a rational choice of the most appropriate vein for catheterization. The deep arm veins should be evaluated with and without a tourniquet.

3. Choice of the appropriate vein at the mid to upper part of the arm. It is recommended that a vein be chosen that is located not deeper than 30 mm from the surface of the skin. To minimize the risk for venous thrombosis, catheters should be inserted in veins whose diameter is at least three times larger than the catheter’s size. Thus vein diameter (in millimeters) should be as large or larger than the external diameter of the catheter in French (Fr) units. For example, a 3-Fr catheter should be placed in a vein 3 mm or larger (equals 9 Fr), a 4-Fr catheter should be placed in a vein 4 mm or larger (equals 12 Fr), and so on.

4. Clear identification of the median nerve and brachial artery. The most effective method to avoid accidental nerve injury is direct visualization of the nerve before and during venipuncture. Although the most important nerve in the arm is the median nerve (adjacent to the brachial artery), the lateral cutaneous nerve of the arm (adjacent to the basilic vein) should be also evaluated. The most effective method to avoid accidental arterial puncture is to identify and visualize the brachial artery before and during any venipuncture.

5. Ultrasound-guided venipuncture. Real-time ultrasound-guided venipuncture of a deep vein (basilic or brachial) is the recommended choice for PICC insertion (Figures 15-3 and 15-4).10 A microintroducer kit is mandatory, preferably with a small-gauge (21-gauge) echogenic needle and a 0.018-inch soft straight-tipped nitinol guidewire. With the possible exception of very “high” punctures close to the axilla, a tourniquet should be used to facilitate the venipuncture.

6. Ultrasound scan of the internal jugular vein during introduction of the PICC. While inserting the catheter into the introducer, the ipsilateral internal jugular vein should be compressed by the ultrasound probe to facilitate passage of the catheter from the subclavian vein into the brachiocephalic vein. After the maneuver, evidence of absence of the catheter in the internal jugular veins on both sides should be obtained by ultrasonography (Figure 15-5).

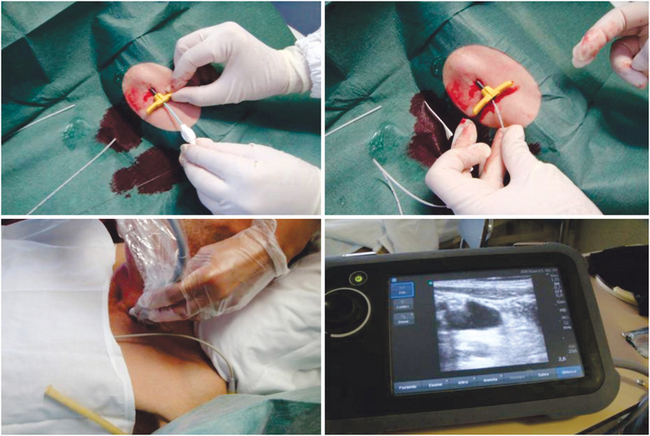

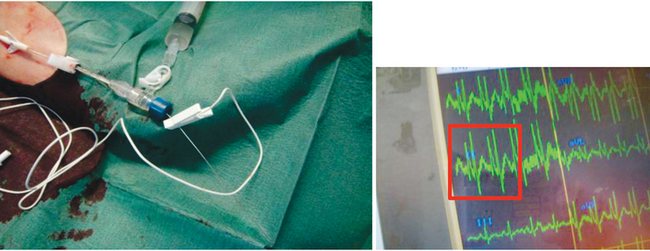

7. Intracavitary electrocardiographic method for assessing tip position (Figure 15-6). The intracavitary electrocardiographic method is an inexpensive, effective, simple, and safe methodology for real-time intraprocedural assessment of catheter tip positioning.14–16 Correct tip positioning (in the proximity of the cavoatrial junction) reduces the risk for catheter malfunction, fibrin sleeves, and catheter-related “central” venous thrombosis. This intraprocedural method aids in evading the cost and risk associated with PICC repositioning. Fluoroscopy, though intraprocedural, is not cost-effective, and a chest radiograph is inevitably a postprocedural method.

Figure 15-6 Intracavitary electrocardiographic technique. The maximum height of the P wave corresponds to the position of the tip at the cavoatrial junction.

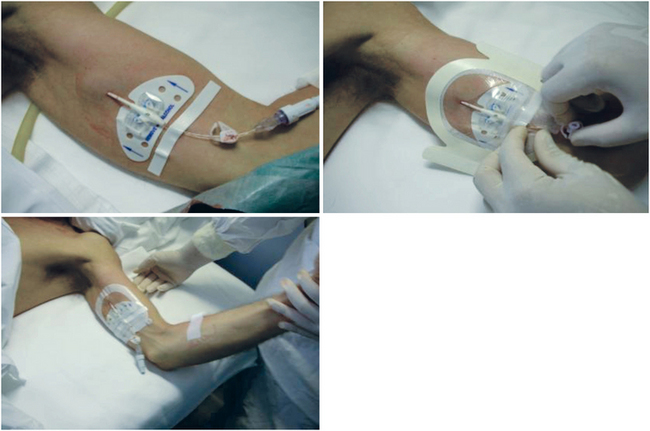

8. Securing the PICC with a sutureless device. The PICC should be secured at the exit site with a sutureless device (Figure 15-7) to decrease the risk for infection, dislocation, and local thrombosis.

Consistent and complete adoption of the SIP protocol reduces the incidence rate of mechanical complications such as insertion failure, repeated punctures, nerve injury, and arterial injury (steps 3, 4, and 5); minimizes malpositioning (steps 6 and 7); and decreases the risk for venous thrombosis (steps 3, 5, and 7), dislocations (step 8), and infections (step 1).9

Pearls and highlights

• The 21st century ultrasound-guided PICC is a different venous access device than the 20th century PICC in terms of indications, complications, and overall clinical performance.

• Routine features of ultrasound-guided PICC insertion are preprocedural visualization of the vein (transverse plane) and implementation of an out-of-plane, “freehand” puncture technique.

• The most commonly accessed veins for PICC insertion are the basilic and brachial veins; however, other arm veins (axillary and cephalic) might be considered.

• Critical issues when choosing a vein for PICC insertion are vein diameter (at least three times larger than the size of the catheter) and depth from the skin surface (veins located deeper than 30 mm should be avoided), as well as the location of the exit site (preferably in the middle third of the upper part of the arm).

• The SIP protocol outlines the main steps in PICC insertion, such as preprocedural evaluation of veins, real-time ultrasound-guided venipuncture, intraprocedural or postprocedural verification of optimal catheter tip positioning by various methods, use of appropriate aseptic techniques and microintroducer kits, and sutureless securement of the catheter at the end of the procedure.

References

1. Sansivero, G, Venous anatomy and physiology: considerations for vascular access devices placement and function. J Intraven Nurs. 1998;21(55):S107–S114.

2. McMahon, D. Evaluating new technology to improve patient outcome. A quality improvement approach. J Infus Nurs. 2002; 25(4):250–255.

3. Sansivero, G. The microintroducer technique for peripherally inserted central catheter placement. J Intraven Nurs. 2000; 23:345–351.

4. Sansivero, G, Use of imaging and microintroducer technology. J Vasc Access Devices 2001;6(1):7–13.

5. Sofocleous, CT, Schur, I, Cooper, SC, et al, Sonographically guided placement of peripherally inserted central venous catheters: review of 355 procedures. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1998;170(6):1613–1616.

6. Royer, T. Nurse driven interventional technology. J Infus Nurs. 2001; 24(5):327–331.

7. Pittiruti, M, Hamilton, H, Biffi, R, et al, ESPEN guidelines on parenteral nutrition: central venous catheters (access, care, diagnosis and therapy of complications). Clin Nutr. 2009;28(4):365–377.

8. Pittiruti, M, La Greca, A, Scoppettuolo, G, et al. Tecnica di posizionamento ecoguidata dei cateteri PICC e Midline. Nutr Ther Metab. 2007; 1:24–35. [SINPE News].

9. Pittiruti, M, Brutti, A, Celentano, D, et al. Clinical experience with power-injectable PICCs in intensive care patients. Crit Care. 2012; 16(1):R21.

10. Simcock, L, No going back: advantages of ultrasound-guided upper arm PICC placement. J Assoc Vasc Access. 2008;13(4):191–197.

11. Lamperti, M, Bodenham, AR, Pittiruti, M, et al. International evidence-based recommendations on ultrasound-guided vascular access. Intensive Care Med. 2012; 38(7):1105–1117.

12. Pratt, RJ, Pellowe, CM, Wilson, JA, et al, EPIC2: national evidence-based guidelines for preventing healthcare-associated infections in NHS hospitals in England. J Hosp Infec. 2007; 65S:S1–S64.

13. O’Grady, NP, Alexander, M, Burns, LA, et al. Healthcare Infection Control Practices Advisory Committee (HICPAC). Guidelines for the prevention of intravascular catheter–related infections. Clin Infect Dis. 2011; 52(9):e162–e193.

14. Pittiruti, M, Scoppettuolo, G, LaGreca, A, et al, The EKG method for positioning the tip of PICCs: results from two preliminary studies. J Assoc Vasc Access. 2008;13(4):179–186.

15. Pittiruti, M, La Greca, A, Scoppettuolo, G. The electrocardiographic method for positioning the tip of central venous catheters. J Vasc Access. 2011; 12(4):280–291.

16. Pittiruti, M, Bertollo, D, Briglia, E, et al, The intracavitary ECG method for positioning the tip of central venous catheters: results of an Italian multicenter study. J Vasc Access. 2012;13(3):357–365.