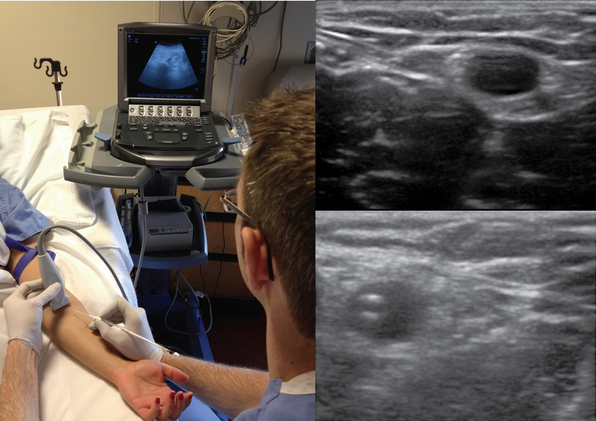

Ultrasound-guided peripheral intravenous access

Ultrasound guidance to obtain vascular access has become increasingly more popular over the past decade. Advances in ultrasound technology have enhanced its ability to detect and interrogate smaller vascular structures for cannulation purposes. Given the potential complications that can develop when accessing central veins, practitioners have turned to ultrasound-guided peripheral access. Although no invasive procedure is without risks, the relative array of complications potentially produced by peripheral, non–centrally extending venous lines tend to be significantly less severe than those from central venous access.1 This chapter outlines the indications, risks, and benefits of ultrasound-guided, noncentral peripheral intravenous (IV) access.

The standard limitations described with landmark-based IV catheter placement can be overcome given the advances in visualization brought to the bedside with ultrasound. With regard to operators, emergency physicians, anesthesiologists, nursing staff, intensivists, and their respective trainees have reported peripheral IV cannulation success rates of higher than 85%.2–7 With regard to risk for infection, Maki et al reported that peripheral IV catheters in general maintain lower infection rates than do any other forms of IV access.1 Additionally, when complications did occur, they tended to not be as morbid as those associated with central venous catheters.

Despite such a successful track record of placement and safety, limited data exist on the role of ultrasound-guided peripheral IV access in patients in the intensive care unit (ICU). One of the reasons for this is that many medications should not be administered through peripheral access given their potentially damaging effects on veins (e.g., certain vasopressors, total parenteral nutrition [TPN]). In another report, medications such as vancomycin or phenytoin were suggested to be associated with increased rates of thrombophlebitis.8 Aside from these relative contraindications, a question remains: in patients who do not need central venous access, are ultrasound-guided peripheral IV techniques reliable enough to allow increased avoidance or removal of central lines in the critically ill? Gregg et al were able to achieve ultrasound-guided peripheral venous access in 99% of patients who failed standard landmark attempts at placement.7 Among the diverse group of trauma, postsurgical, and cardiac intensive care patients, 34 central lines were avoided and 40 were removed as a result of adequate peripheral access. In a small randomized controlled trial, Kerforne et al also demonstrated increased success rates of ultrasound-guided peripheral IV access over the landmark technique in critical care patients who were deemed to have difficult access.9 Despite reports of relatively low complication rates with ultrasound-guided peripheral IV access in the ICU,7 no trials have directly compared rates of infection or thrombophlebitis with the use of ultrasound-guided versus landmark techniques.

Different techniques for placing peripheral IV catheters have been described. One-person operation of the ultrasound transducer while placing the IV line has the benefit of allowing the entire procedure to be performed by a single party. However, applying appropriate skin tension when limited to a single hand to perform the insertion has the potential to be awkward. This has led to reports of a two-person technique that involves an ultrasound operator and an IV operator working together throughout the placement procedure. Chinnock et al showed that the number of operators placing the IV line was not predictive of successful placement,10 and a variety of other studies describing either a one- or two-person technique have shown successful placement more than 85% of the time.2–7 Another variation in equipment described includes the use of guidewire assistance. Guidewire-assisted vascular access devices have traditionally been used when attempting arterial access; however, given their ease of use, successful single-operator cannulation rates higher than 95% can be achieved.7–11 The limitation of catheters with wires that are preloaded onto the device is that the IV lines tend to come in limited diameters. To overcome this shortcoming, Sandhu and Sidhu described a technique that allows upsizing an access catheter to a larger-bore one by means of exchanging the device over a free wire.4 It is this author’s preference to use wire-assisted devices for single-operator placement of peripheral IV lines when larger-bore access is not necessary.

Pearls and pitfalls

Pearls

Anatomy

• Any of the named veins in the arm can be candidates for access. However, the radial vein in the midforearm region tends to be the best access point. It is usually deep enough that it is not routinely accessed because of limited visualization with landmark techniques, yet it is easily detected with ultrasound.

Technical tips

• Get comfortable. Performing the procedure while sitting down is preferable.

• Have multiple catheters available in the event of unsuccessful cannulation.

• Tape the forearm to the bed in a supinated position.

• Place a tourniquet above the biceps to occlude superficial blood return.

• Have all dressing supplies ready to apply.

• Prepare the skin with chlorhexidine—use it as ultrasound medium. A clear plastic adhesive dressing may be applied to the transducer to protect it.

• Ensure that the vessel collapses—if not, be concerned for thrombosis or that the vessel may be an artery. IV catheters may be placed above areas with short segments of thrombosis of the superficial veins. Tributaries may keep these proximal areas patent.

• Use high-frequency transducers with the depth set to around 2 cm to achieve the best resolution of superficial veins.

• Apply an elastic tourniquet to augment the vein’s diameter.

• Use gentle pressure on the skin when scanning to avoid inadvertent collapse or nonvisualization of veins, or both.

• Consider using a catheter with a guidewire to assist in the placement process. If unavailable, a standard IV catheter can be used.

• Use a catheter of appropriate length to allow proper seating within the vein. Catheters that are minimally 1.75 inches in length tend to be long enough to reach the deeper veins of the forearm.

• Once the vein is accessed and the wire has passed into the vein, gently rotate the catheter over the wire while it is being advanced into the vein. It should slide smoothly over the wire and not meet any resistance.

• Confirm placement by attaching a saline-filled syringe with extension tubing to the catheter and flushing. Turbulence can be seen within the vein on ultrasound during flushing.

• Suturing the IV line in place is not necessary; the IV line may be taped or a clear plastic dressing may be applied.

Pitfalls

• Veins smaller than 2 mm in diameter tend to be difficult to cannulate or detect by ultrasound, and long-term patency may be limited.

• Cannulating the venae comitantes of an artery is not usually successful given their tortuosity. Try to cannulate veins away from the arteries.

• The deeper the basilic vein runs, the longer the catheter will be needed to span the distance of the subcutaneous tissue. Try to access it closer to the elbow to ensure enough intravessel catheter length.

• Veins on the dorsal surface of the hand tend to be difficult to visualize with ultrasound because of limited subcutaneous tissue in this area. Consider the landmark technique when attempting to access these veins.

References

1. Maki, DG, Kluger, DM, Crnich, CJ, The risk of bloodstream infection in adults with different intravascular devices: a systematic review of 200 published prospective studies. Mayo Clin Proc. 2006;81(9):1159–1171.

2. Keyes, LE, Frazee, BW, Snoey, ER, et al. Ultrasound-guided brachial and basilic vein cannulation in emergency department patients with difficult intravenous access. Ann Emerg Med. 1999; 34(6):711–714.

3. Costantino, TG, Parikh, AK, Satz, WA, et al. Ultrasonography-guided peripheral intravenous access versus traditional approaches in patients with difficult intravenous access. Ann Emerg Med. 2005; 46(5):456–461.

4. Sandhu, NP, Sidhu, DS. Mid-arm approach to basilic and cephalic vein cannulation using ultrasound guidance. Br J Anaesth. 2004; 93(2):292–294.

5. Aponte, H, Acosta, S, Rigamonti, D, et al. The use of ultrasound for placement of intravenous catheters. AANA J. 2007; 75(3):212–216.

6. Blaivas, M. Ultrasound-guided peripheral i.v. insertion in the ED. Am J Nurs. 2005; 105(10):54–57.

7. Gregg, SC, Murthi, SB, Sisley, AC, et al. Ultrasound-guided peripheral intravenous access in the intensive care unit. J Crit Care. 2010; 25(5):514–519.

8. Maki, DG, Ringer, M. Risk factors for infusion-related phlebitis with small peripheral venous catheters. A randomized controlled trial. Ann Intern Med. 1991; 114(10):845–854.

9. Kerforne, T, Petitpas, F, Frasca, D, et al. Ultrasound-guided peripheral venous access in severely ill patients with suspected difficult vascular puncture. Chest. 2012; 141(1):279–280.

10. Chinnock, B, Thornton, S, Hendey, GW. Predictors of success in nurse-performed ultrasound-guided cannulation. J Emerg Med. 2007; 33(4):401–405.

11. Mahler, SA, Wang, H, Lester, C, et al. Ultrasound-guided peripheral intravenous access in the emergency department using a modified Seldinger technique. J Emerg Med. 2010; 39(3):325–329.