Ultrasound-guided percutaneous tracheostomy

Overview

Kearney et al1 reported rates of perioperative morbidity of 6% and procedure-related mortality of 0.6%. Placement complications include hemorrhage, accidental extubation, pneumothorax, formation of a false passage, damage to tracheal rings, and perforation of the posterior tracheal wall. Delayed bleeding is typically seen a few days after PT and is due to either minor vessel damage or erosion into high or aberrant mediastinal vessels. The latter can be life-threatening and necessitates immediate surgical input. The most important late complications are tracheal stenosis, tracheomalacia, and vocal cord dysfunction, which could adversely affect the quality of life of ICU survivors.1,2

Point-of-care ultrasound (US) is increasingly being used for the management of critically ill patients. Despite wide application, US-guided percutaneous tracheostomy (USGPT) is not yet routine practice in many centers. Preprocedural, real-time US can reduce some of the complications just mentioned, morbidity, and possibly the occasional mortality associated with PT.3–8 This chapter focuses on the role of US for PT, the sonographic anatomy of the anterior neck region, and the evidence available for USGPT.

Sonographic anatomy of the anterior neck region

Typically, a high-frequency (5- to 10-MHz), high-resolution, small-footprint, vascular-type linear probe is used for US scanning of the trachea and paratracheal area. Because air within the larynx and trachea has very high acoustic impedance, which results in high reflectance of the sound waves, US has limited ability to depict the inside of the air-filled airways and generates a characteristic acoustic shadow. Despite this shortfall, the superficial location of the larynx and trachea allows delineation and visualization of the anterior and lateral walls. Both the thyroid and cricoid cartilage are clearly visible as midline echogenic structures separated by the echolucent cricothyroid membrane with characteristic acoustic shadow underneath.4,5 Below, the cartilaginous tracheal rings, which are characterized by a thin acoustic shadow, are easily visible along with pretracheal tissue and vessels.

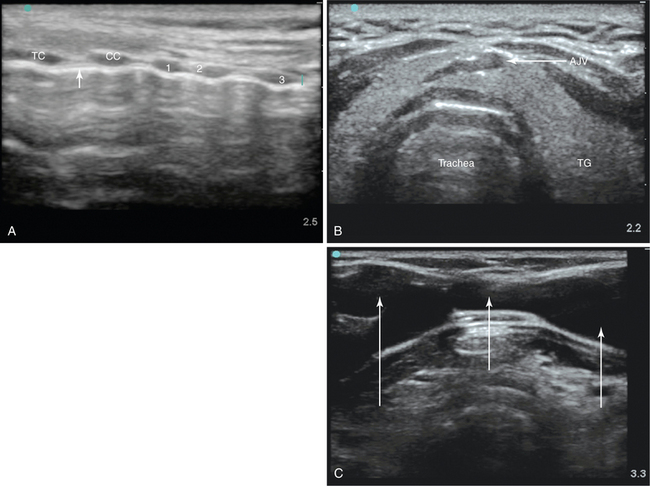

In the longitudinal view, the thyroid, cricoid cartilage, and individual tracheal rings can be seen anterior to the hyperechogenic line formed by the air-tissue interface at the anterior tracheal wall. The longitudinal view allows identification of the intercartilaginous spaces and selection of the most appropriate needle puncture site, which can be performed in real time with a sterile probe cover. However, the need for a probe with a small physical footprint and the inability to visualize the posterior wall of the trachea and paratracheal structures may limit the usefulness of this approach (Figure 52-1A).4,5

Figure 52-1 A, Longitudinal ultrasound (US) scan of the neck. The anterior tracheal wall is indicated by the white arrow. CC, Cricoid cartilage, first, second, and third tracheal cartilages; TC, thyroid cartilage. B, Transverse view of the trachea showing the joined anterior jugular veins (AJV). TG, Thyroid gland. C, Extensive venous plexus depicted on US examination (white arrows) in an elderly patient with severe tricuspid regurgitation.

The transverse view enables simultaneous visualization of nearby tissue and blood vessels, including the thyroid lobes, isthmus, and major vessels. PT through the thyroid isthmus is permitted as long as vulnerable vessels are avoided.4,5 In a large proportion of PT procedures the thyroid isthmus is traversed, and this may be unavoidable.4,5 The diameter and location of the anterior jugular veins (midline or near midline) can be delineated and vulnerable vessels can be electively ligated or avoided to reduce the risk for intratracheal bleeding (Figure 52-1B).5

Life-threatening hemorrhage can arise from unintended damage to the carotid, brachiocephalic, and subclavian arteries. The immediate paratracheal carotid arteries are vulnerable to such injury from placement of the needle and dilator in a nonmidline position. A major advantage of US is the ability to depict and delineate abnormal anatomy (e.g., a high-riding brachiocephalic trunk) and aberrant vessels (Figure 52-1C), including thyroid arteries near the midline, for example, the thyroidea ima artery, which occurs in 3% to 10% of the population.

Real-time tracheal puncture is characterized by an acoustic shadow ahead of the advancing needle, displacement of pretracheal tissue, and indentation of the anterior wall of the trachea associated with a palpable change in resistance as the needle passes through the anterior tracheal wall. This technique may be particularly useful in patients with limited neck movement, a potentially unstable cervical spine, suboptimal anatomy, and morbid obesity.9

With the head in a neutral position, the thickness of the soft tissue between the skin and trachea can be measured, as well as the internal diameter of the trachea. Such measurements will help in making decisions regarding the need for an extended-length tracheostomy tube and appropriate size of tube. The need for longer tracheostomy tubes has been reported.10 Postprocedural US examination of the chest is useful to check for pleural complications.4

Evidence for ultrasound-guided percutaneous tracheostomy

Most of the current literature on the use of US before or during PT is derived from small observational studies and case series. However, a substantial body of high-quality evidence recommends US guidance for various other diagnostic and therapeutic interventions, and it is likely that application of US before PT will become routine practice.

Kollig et al6 reported a change in the planned tracheostomy site in 24% of patients after US scanning of the anterior neck region. In another study, significant bleeding occurred in 24 of 497 (5%) patients after PT, and in 6 of 24, PT was converted to a surgical procedure. The authors concluded that bleeding could have been avoided had US been performed before PT.7

The anterior jugular vein was vulnerable in 8 of 30 patients, and 4 had potentially vulnerable arteries requiring a change in puncture site, elective ligation of vulnerable vessels, and modification of the procedure.5

A postmortem report revealed cranial misplacement in a third of patients who underwent PT without US guidance, whereas satisfactory tube placement was confirmed in all patients who underwent US scanning before PT.8 In a recent study, real-time US guidance facilitated safe and successful PT in 13 patients with head injury and allowed less frequent endoscopic guidance.9

Pearls and highlights

• Routine US scanning of the anterior neck region before PT enables visualization and identification of airway structures and the midline of the trachea, selection of the most appropriate stoma site, and depiction of vulnerable blood vessels and associated structures. This information can help in formulating the most appropriate procedure for individual patients.

• Tracheal depth and diameter and the skin-to-trachea distance can be measured and the appropriate size and length of tube chosen.

• Real-time USGPT can increase the safety and accuracy of the procedure, particularly in patients with morbid obesity or suboptimal anatomy, and avoid some of the drawbacks associated with endoscopy.

References

1. Kearney, PA, Griffen, MM, Ochoa, JB, et al. A single-center 8-year experience with percutaneous dilational tracheostomy. Ann Surg. 2000; 231(5):701–709.

2. Engels, PT, Bagshaw, SM, Meier, M, Brindley, PG, Tracheostomy: from insertion to decannulation. Can J Surg. 2009;52(5):427–433.

3. Mallick, A, Bodenham, AR. Tracheostomy in critically ill patients. Eur J Anaesthesiol. 2010; 27(8):676–682.

4. Susti´c, A. Role of ultrasound in the airway management of critically ill patients. Crit Care Med. 2007; 35(5 suppl):S173–S177.

5. Hatfield, A, Bodenham, A. Portable ultrasonic scanning of the anterior neck before percutaneous dilatational tracheostomy. Anaesthesia. 1999; 54(7):660–663.

6. Kollig, E, Heydenreich, U, Roetman, B, et al, Ultrasound and bronchoscopic controlled percutaneous tracheostomy on trauma ICU. Injury. 2000;31(9):663–668.

7. Muhammad, JK, Patton, DW, Evans, RM, Major, E. Percutaneous dilatational tracheostomy under ultrasound guidance. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1999; 37(4):309–311.

8. Susti´c, A, Kovac, D, Zgaljardi´c, Z, et al, Ultrasound-guided percutaneous dilatational tracheostomy: a safe method to avoid cranial misplacement of the tracheostomy tube. Intensive Care Med. 2000;26(29):1379–1381.

9. Rajajee, V, Fletcher, JJ, Rochlen, LR, Jacobs, TL, Real-time ultrasound-guided percutaneous dilatational tracheostomy: a feasibility study. Crit Care. 2011;15(1):R67.

10. Mallick, A, Bodenham, A, Elliot, S, Oram, J. An investigation into the length of standard tracheostomy tubes in critical care patients. Anaesthesia. 2008; 63(3):302–306.