Ultrasonography: A basic clinical competency

Overview

Ultrasound is a safe imaging modality and should be considered “first” in many clinical scenarios when imaging is indicated, especially those involving children to avoid the risk for cancer from ionizing radiation (i.e., ultrasound versus computed tomography for the diagnosis of appendicitis).1–3 The cost of ultrasound imaging is also considerably less than that of most other imaging modalities, and it can provide equivalent or better images and thus decrease overall health care cost. When compared with other imaging modalities, ultrasound has the added advantage of providing dynamic examinations, such as evaluation of the shoulder for rotator cuff disease or real-time guidance of procedures such as central line placement and thoracentesis.

Ultrasonography in medical student education

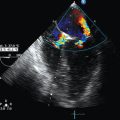

Ultrasound was introduced into medical student education in the 1990s and proved to be a valuable teaching tool in courses such as anatomy, physiology, and physical examination.4–6 Ultrasound education gradually expanded into the clinical years of medical school, especially in the discipline of emergency medicine.7 The clinical application of ultrasound being taught is as a focused or point-of-care examination designed to answer a specific clinical question such as “Is there a gallstone in the gallbladder that helps explain this patient’s right upper quadrant abdominal pain?” or “Is there overall normal heart function in this patient with shortness of breath?” This point-of-care ultrasound approach has been highly developed in the emergency department setting, and the American College of Emergency Physicians has led the way in defining the necessary training and competencies in point-of-care ultrasound.8

In recent years, ultrasound has been successfully integrated across the entire medical student curriculum. Hoppmann et al reported on 4 years of experience with an integrated ultrasound curriculum.9 As part of the curriculum, all students at the end of the anatomy course in the first year of medical school are observed individually and evaluated for their ability to perform ultrasound on standardized patients and capture and identify anatomic structures in a series of specific ultrasound images. Such structures included the kidney, liver, and Morison pouch in the right upper abdominal quadrant; kidney and spleen in the left upper abdominal quadrant; urinary bladder in the pelvis; carotid artery and internal jugular vein in the neck; and parasternal long-axis view of the heart. The mean percentage of correct responses after 3 years of these examinations was 97.1%. In addition, from student surveys of the same ultrasound curriculum, more than 90% of students thought that the curriculum had enhanced their medical education, allowed increased clinical correlation with basic science instruction, and improved their understanding and skills of the physical examination.

Ultrasound across multiple specialties

Widely used in radiology, cardiology, and obstetrics and gynecology for several decades, ultrasound is now rapidly expanding across many specialties from pediatrics to critical care medicine and orthopedic surgery.10 In addition, the list of clinical applications for ultrasound has grown considerably in recent years and will probably continue to grow as more practitioners explore new applications of ultrasound to improve patient care and safety in their particular specialty.

Competency-based medical education

If ultrasonography is to be a basic clinical competency, it is essential that educational programs be developed that result in competent users of this technology. In its most basic definition, competency would be the ability of an individual to do a job properly.11 There has been increasing pressure in recent years in medical education globally to move from a time- and process-based system of training to a competency-based training framework.12

Frank et al outlined six stages in planning competency-based medical education.13 Step 1 calls for identification of the abilities needed by graduates to provide a high standard of patient care based on evidence and expert consensus. Starting with the abilities needed by the practitioner and then working backward to develop the appropriate educational program constitute the essence of competency-based education. Step 2 calls for well-defined competency components that fit together to define a competent practitioner. In step 3, milestones are determined along the developmental path to competency. These milestones are sequenced in a logical fashion to form a foundation of skills and knowledge on which to build to the desired level of competency. In step 4, the educational activities, experiences, and instructional methods are determined to reach these milestones. Step 5 calls for assessment tools to measure student progress, and finally, step 6 requires that a method be in place to evaluate the educational program as a whole.

Critical care ultrasound

Dozens of applications of ultrasound have been identified in critical care medicine.14 It has also been shown that ultrasound examination reveals significant unsuspected clinical abnormalities in patients admitted to the intensive care unit.15,16

A review of intensive care medicine in 2011 highlighted a number of applications and trends of ultrasound use in critical care medicine, among which were the rapidly evolving use of ultrasound to detect pneumothorax, intracranial hypertension by measuring the diameter of the optic nerve sheath, and gastric fluid with the potential to reduce the risk for aspiration during endotracheal intubation.17

There is little doubt that ultrasound should be a competency of critical care practitioners; in fact, there was 100% agreement among a panel of international experts in critical care ultrasonography that “general critical ultrasound and basic critical care echocardiography should be mandatory in the curriculum of intensive care unit physicians.”18 The expert panel defined clinical competencies in the field, and these are serving as a practical guide for physicians seeking training and those who train physicians in critical care ultrasonography.19

Electronic portfolio

Determining a student’s competency formatively during medical school and then at the end of a course or medical school could be done and documented by way of a student ultrasound electronic portfolio. There are numerous advantages of an electronic portfolio for undergraduate medical education.20 Students can document their activities and provide evidence to demonstrate their development of competencies. Portfolios also provide reflective practice and are an excellent platform for dialogue and mentoring with faculty.

Conclusion

Ultrasound has the potential to transform medical education and the practice of medicine for the benefit of patient and learner alike. Ultrasound is a safe and valuable teaching and clinical practice tool. Its expanding role in clinical applications, multiple medical specialties, and clinical settings speaks to its value for a wide variety of practitioners. Ultrasonography should be given serious consideration as a basic clinical competency for all physicians and many other health care providers. Ultrasound instruction should begin in medical school with a competency-based curriculum and continue throughout the professional career of the practitioner. There is strong support for ultrasound as an essential critical care medicine competency. An electronic ultrasound portfolio could prove to be an effective way to manage ultrasound curricula and postgraduate training and document ultrasound competency in practitioners over time.

Pearls and highlights

• Ultrasound is a safe imaging modality for users and patients.

• Ultrasound is a valuable teaching tool for basic science and clinical medicine.

• Medical students can learn ultrasound basics very well.

• Ultrasonography can improve patient care and safety and decrease health care cost.

• Ultrasonography has applications across many specialties in medicine and can be applied in virtually every clinical setting.

• Ultrasound provides dynamic imaging.

• The size and cost of ultrasound systems have made them more accessible to practitioners.

References

1. Nazarian, LN. Sound judgment. J Ultrasound Med. 2012; 31(2):187.

2. Goldstein, SR. The sound judgment series. J Ultrasound Med. 2012; 31:189–190.

3. Linam, LE, Munder, M. Sonography as the first line of evaluation in children with suspected acute appendicitis. J Ultrasound Med. 2012; 31:1153–1157.

4. Brunner, M, Moeslinger, T, Spieckermann, PG, Echocardiology for teaching cardiac physiology in practical student courses. Am J Physiol. 1995;6 Pt 3:S2–S9.

5. Teichgräber, UK, Meyer, JM, Poulsen, NC, Von Rautenfeld, DB, Ultrasound anatomy: a practical teaching system in human gross anatomy. Med Edu. 1996; 30:296–298.

6. Barloon, TJ, Brown, BP, Abu-Yousef, MM, et al. Teaching physical examination of the adult liver with use of real-time sonography. Acad Radiol. 1998; 5:101–103.

7. Cook, T, Hunt, P, Hoppmann, R, Emergency medicine leads the way for training medical students in clinician-based ultrasound: a radical paradigm shift in patient imaging. Acad Emerg Med. 2007;14(6):558–561.

8. Jang, TB, Coates, WC, Liu, YT. The competency-based mandate for emergency bedside sonography training and a tale of two residency programs. J Ultrasound Med. 2012; 31:515–521.

9. Hoppmann, RA, Rao, VV, Poston, MB, et al, An integrated ultrasound curriculum (iUSC) for medical students: 4-year experience. Crit Ultrasound J. 2011;3(1):1–12.

10. Moore, CL, Copel, JA. Point-of-care ultrasonography. N Engl J Med. 2011; 364:749–757.

11. Wikipedia contributors. Competence (human resources). Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. Available at http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Competence_(human_resources), March 25, 2013. [Accessed].

12. Frank, JR, Mungroo, R, Ahmad, Y, et al, Toward a definition of competency-based education in medicine: a systematic review of published definitions. Med Teac. 2010; 32:631–637.

13. Frank, JR, Snell, LS, Cate, OT, et al, Competency-based medical education: theory to practice. Med Teac. 2010; 32:638–645.

14. Neri, L, Storti, E, Lichtenstein, D. Toward an ultrasound curriculum for critical care medicine. Crit Care Med. 2007; 35(5 suppl):S290–S304.

15. Manno, E, Mavarra, M, Faccio, L, et al, Deep impact of ultrasound in the intensive care unit: the “ICU-sound” protocol. Anesthesiology. 2012;117(4):801–809.

16. Karabinis, A, Karakitsos, D, Saranteas, T, Poularas, J. Ultrasound-guided techniques provide serendipitous diagnostic information in anaesthesia and critical care patients. Anaesth Intensive Care. 2008; 36:748–749.

17. Antonelli, M, Bonten, M, Chastre, J, et al. Year in review in intensive care medicine 2011. II. Cardiovascular, infections, pneumonia and sepsis, critical care organization and outcome, education, ultrasonography, metabolism and coagulation. Intensive Care Med. 2012; 38:345–358.

18. Expert Round Table on Ultrasound in ICU. International expert statement on training standards for critical care ultrasonography. Intensive Care Med. 2011; 37(7):1077–1083.

19. Mayo, PH, Beaulieu, Y, Doelken, P, et al. American College of Chest Physicians/La Société de Réanimation de Langue Française Statement on competence in critical care ultrasonography. Chest. 2009; 135(4):1050–1060.

20. Hall, P, Byszewski, A, Sutherland, S, Stodel, EJ. Developing a sustainable electronic portfolio (ePortfolio) program that fosters reflective practice and incorporates CanMEDS competencies into the undergraduate medical curriculum. Acad Med. 2012; 87:744–751.