CHAPTER 36 Ulnar Head Implants: Unconstrained

The ulnar head is the keystone for mobility and stability of the ulnar-sided wrist as well as the forearm. It not only is one of the joint partners creating the distal radioulnar joint (DRUJ) but also represents an integral part of the wrist joint. Biomechanically, it represents the only fixed, nonmoving anatomical structure at the wrist level. It, therefore, supplies the bony support around which the radius with the wrist and hand rotates in the DRUJ. Arthrotic destruction of the DRUJ will lead to painful limitation of forearm rotation and reduction of grip strength and therefore compromise hand function. Arthrotic derangement may be the result of intra-articular fractures of the DRUJ either with direct damage of the cartilage of the ulnar head or the sigmoid notch in comminuted fractures or secondary destruction due to intra-articular malunion of the joint line. However, the most common origin consists of the malunited extra-articular distal radius fracture. The dorsal or palmar angulation of the distal radial fragment with loss of the physiological ulnar inclination and shortening of the radius will lead to incongruity of the DRUJ and over time result in arthrotic derangement of this joint. I, therefore, consider the malunited extra-articular distal radius fracture a prearthrotic deformity of the DRUJ.1

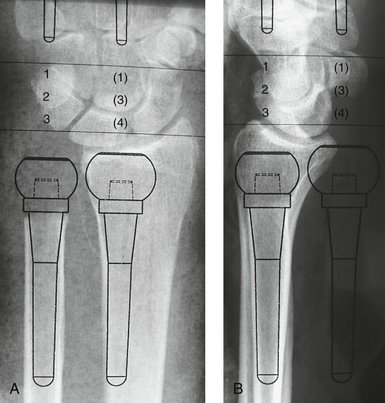

Several salvage procedures have been described to reduce the pain and restore forearm rotation in patients with symptomatic DRUJ destruction, including ulnar head resection2–4 and the hemi-resection interposition technique.5 Partial loss of the ulnar head sacrifices the attachment of the palmar ulnocarpal ligaments and the force transfer from the radius onto the ulnar head. Loss of the ligament attachment will result in a palmar drop of the ulnar-sided wrist with a supination deformity of the hand and a dorsally prominent distal end of the ulna. In a way this is comparable to the well-described caput ulnae deformity in rheumatoid patients. The deformity does not truly represent an “instability of the distal end of the ulna” but an instability of the ulnar-sided wrist. Loss of the bony support of the radius in the DRUJ leads to radioulnar narrowing or impingement during forearm rotation and wrist loading and can radiologically be demonstrated on the transverse loading stress views described by Lees and Scheker (Fig. 36-1).6

A completely different concept to treat the painfully destroyed DRUJ consisting of fusion of the DRUJ and segment resection proximal to the ulnar head to restore forearm rotation was described by Sauvé and Kapandji in 1936.7 With this procedure the supination deformity and the instability at the DRUJ level is prevented as the attachments of the ulnopalmar ligaments and the triangular fibrocartilage complex (TFCC) remain. However, in pronation underloading of the hand the dynamic dorsal stabilizers of the radius and the wrist may not be sufficient to prevent palmar drop of the wrist and hand in relation to the distal end of the ulna, therefore leading again to a dorsally prominent distal ulnar stump. Furthermore, on transverse loading of the hand there is no anatomical structure to prevent the radius to fall onto the distal end of the ulna, resulting in radioulnar impingement (Fig. 36-2).8,9

The concept to prevent development of this instability using an ulnar head spacer in rheumatoid patients was first described by Swanson.10 This is no longer recommended because of the high failure rate of the Silastic spacer material and secondary Silastic-induced synovitis.11–15

To overcome the secondary “painful instability of the distal ulna,” several stabilizing soft tissue procedures using part of the flexor and/or the extensor carpi ulnaris tendon have been described. None of these procedures was found to reliably restore the stability or reduce symptoms in biomechanical16 or clinical17,18 studies. Wide resection of the ulna19 as well as lengthening procedures after excessive shortening of the ulna20 have been advocated but did not resolve the symptoms in my own or other surgeons’ experience.17 Considering the biomechanical and clinical shortcomings of the above-described resection procedures, Herbert developed the concept of restoring stability to the DRUJ as well as the wrist joint and the continuity of the ulna by means of an ulnar head prosthesis.

Following the development of the prosthesis a three-phase clinical study design was developed. Initially, three patients with painful instability of the wrist and forearm after resection arthroplasty were treated in 1995 with promising early results.21 The second phase consisted of a prospective multicenter study limited to another 20 patients. Because of the excellent mid-term results of these patients,22 the prosthesis was released to other surgeons. The third phase consisted of the evaluation of the long-term results, and all patients with a follow-up of more than 5 years are currently under review.

Indications

Other Indications

Primary osteoarthrosis of the DRUJ is a rare condition but represents an ideal indication for ulnar head replacement because there is no additional DRUJ pathological process that must be addressed at the time of surgery. It frequently affects middle-aged active patients who expect normal performance of the wrist and hand in their professional and private life (Fig. 36-3). The same applies for patients with a giant cell tumor of the ulnar head requiring ulnar head resection.

Another major indication for ulnar head replacement is as a revision procedure in patients with painful instability of the wrist and forearm after previous resection arthroplasties (hemi-resection or complete resection of the ulnar head) or a Sauvé-Kapandji procedure. The long-term experience with this difficult group of patients has proved that reconstruction of the DRUJ using the ulnar head prosthesis is an effective method to cure the problem. However, revision surgery is often difficult and less predictable than when the operation is carried out as a primary procedure. In patients with painful instability after a Sauvé-Kapandji procedure two options for reconstruction are available. Resection of the fusion mass and insertion of the prosthesis is recommended if either the fusion has not healed completely or the original fusion has been performed in an ulnar-positive variance situation leading to additional symptoms of ulna impaction syndrome. In all other cases a spherical head, designed by Fernandez and colleagues,23 may be used to articulate within the previously fused ulnar head after reaming of a socket into the proximal fusion mass.

Surgical Technique

Radiographic templates are used to plan the appropriate resection level and implant.

Primary Ulnar Head Replacement

An ulnar-based capsuloretinacular flap is outlined and raised as previously described.21,22,24 It includes the extensor retinaculum, the dorsal capsule of the DRUJ, and the sixth extensor compartment, including the extensor carpi ulnaris tendon. The incision is placed along the floor of the fifth extensor compartment and extends from the dorsal shaft of the ulna proximally to the dorsal ulnocarpal joint distally. The dorsal rim of the TFCC is identified, and the flap is carefully raised in one layer along the dorsal radioulnar ligament toward the ulnar styloid process, completely exposing the ulnar head proximally and the ulnocarpal joint distally. The floor of the sixth extensor compartment should be kept intact or repaired to protect the tendon from direct contact with the prosthesis.

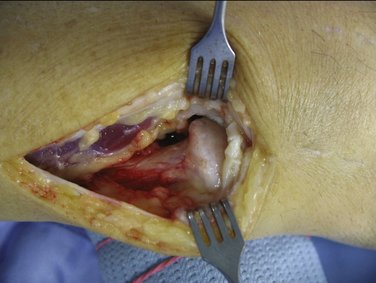

At this stage the bone quality and the soft tissue flap are checked. Additionally, the joint surfaces of the DRUJ are inspected to confirm the diagnosis of osteoarthritis and to make the final decision on ulnar head replacement (Fig. 36-4).

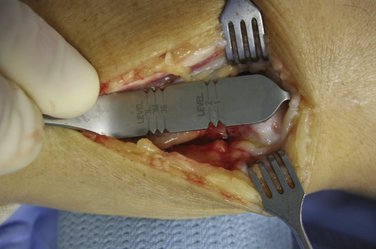

The hook of the resection guide is now engaged over the distal end of the radius and the resection level, as preoperatively determined using the radiographic template, is marked on the neck of the ulna (Fig. 36-5). With a small power saw the osteotomy is performed perpendicular to the long axis of the ulna.

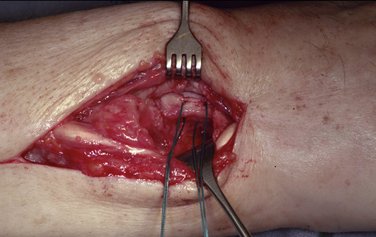

After removal of the ulnar head the distal ulna is lifted dorsally using the special soft tissue retractor provided. The medullary canal of the ulnar shaft is opened using the broach and then reamed to the appropriate diameter with the hand reamer according to the preoperatively determined size (Fig. 36-6). The reamer should completely fit into the medullary canal to allow later insertion of the shaft of the prosthesis.

Two drill holes are now placed through the dorsal rim of the sigmoid notch, and strong nonabsorbable sutures are passed to allow later reattachment of the flap (Fig. 36-7).

FIGURE 36-7 Transosseous sutures through the dorsal rim of the sigmoid notch for reattachment of the soft tissue flap.

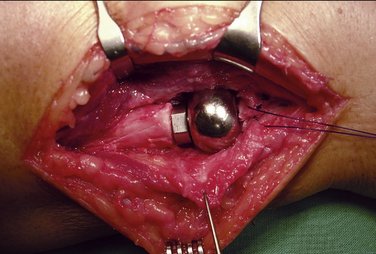

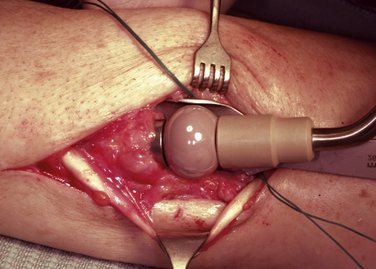

The appropriate trial prosthesis is now inserted and reduced into the sigmoid notch (Fig. 36-8). Seating of the head of the prosthesis within the sigmoid notch as well as the tension of the TFCC over the head in full pronation is now examined. The elbow is now flexed into a 90-degree position, and the position of the prosthesis as well as the ulnar variance is checked using the image intensifier. Radiologically, ulnar variance should measure −1 to −2 mm at the wrist level in neutral forearm rotation. If necessary, the trial prosthesis should be removed and a more proximal resection of the ulna is performed. In case of a too-proximal resection of the ulna with excessive ulnar-negative variance, this can be corrected by reverting to a stem with a built-up collar.

The cone end of the shaft is now cleaned to ensure a good interference fit between the two components; then the head is impacted onto the stem (Fig. 36-9).

FIGURE 36-9 Insertion of the definitive prosthesis and the head of the prosthesis on the cone of the shaft.

The elbow is again flexed into a 90-degree position with the forearm elevated and in 30 degrees of supination. The dorsal rim of the TFCC is reattached to the underside of the flap using the previously placed sutures. The flap is advanced and reattached under the appropriate tension to the radius using the transosseous sutures (Fig. 36-10). The repair is completed by suturing the remainder of the flap to the ulnar rim of the extensor retinaculum of the fourth extensor compartment, leaving the EDM tendon subcutaneous.

Revision Surgery after Resection Arthroplasties

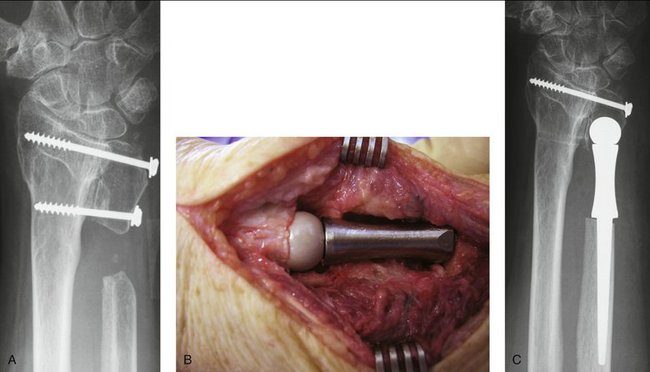

In revision surgery, radiographs of both wrists have to be available. Analysis of the radiographs includes a determination of the individual ulnar variance at the wrist level and the amount of length of the distal ulna that has to be covered to create a new DRUJ. With the use of the radiographic templates, a decision needs to be made whether there remains sufficient ulnar length for a standard stem or whether a revision stem will be required (Fig. 36-11). In cases of excessive previous shortening of the ulna a custom-made prosthesis with additional length of the collar of the shaft of the prosthesis may be required.

Revision Surgery after Sauvé-Kapandji Procedures

To resolve a painful instability after a Sauvé-Kapandji procedure two options are possible that must be decided on before surgery. Either the arthrodesis of the ulnar head is taken down and a prosthesis is used in a similar manner to that of revision surgery for failed resection arthroplasties or a bony ball-and-socket joint is created underneath the fused ulnar head using the prosthesis with a special spherical head as described by Fernandez and associates.23

Removal of the ulnar head is indicated in cases in which fusion of the DRUJ has been performed in an ulnar-positive variance situation, leading to additional symptoms of ulna impaction syndrome or if the fusion has not healed completely. In all of these cases a prosthesis with a revision shaft will be required because the previous resection level is far proximal to the neck of the ulnar head (Fig. 36-12). In some cases a custom-made shaft may be required to restore the length of the ulna, which must be determined before the surgery using the radiographic templates. The procedure is performed in a similar manner as that for revising a resection arthroplasty with the following exceptions.

If the ulnar head has been fused in an anatomical position, stability may be restored by creating a ball-and-socket joint under the fusion mass (Fig. 36-13). A longitudinal incision is placed dorsally over the ulnar head extending proximally to the dorsal aspect of the distal end of the ulnar shaft. The distal end of the ulna as well as the proximal end of the fusion mass is exposed. With the use of a special power reamer a spherical cavity is created underneath the proximal end of the fused ulnar head to later contain the spherical head of the prosthesis. Preparation of the ulnar shaft and determination of the appropriate-sized shaft of the prosthesis is performed in a similar fashion to that of a primary procedure. Because in this procedure bony stabilization rather than soft tissue stabilization is the aim, the spherical cavity will have to cover at least one third of the spherical head of the prosthesis. After implantation of the shaft and impaction of the spherical head on the cone of the prosthesis, reduction of the head into the bony cavity may not be possible. Osteotomy of the radius with additional plate osteosynthesis may be needed after reduction of the prosthesis.

Complications

Recurrent Instability

Failure of the soft tissue flap is most commonly due to improper patient selection. Insufficient soft tissues due to rheumatoid patients or as a result of several previous procedures at the DRUJ represent a contraindication for the procedure. This may need to be determined intraoperatively and may necessitate abandoning the procedure. Choice of the correct-sized head of the prosthesis as well as thorough preparation and repair of the flap are crucial for the success of the operation.

Results

Clinical Results

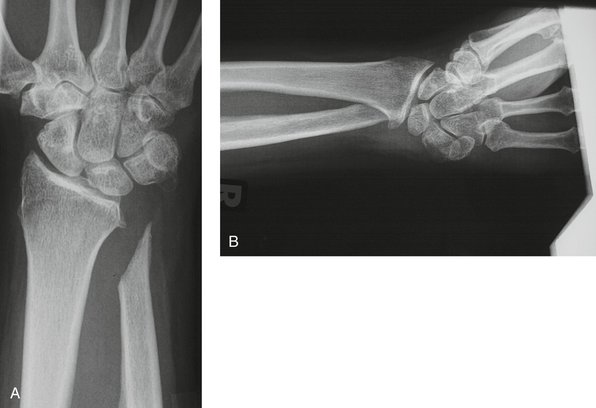

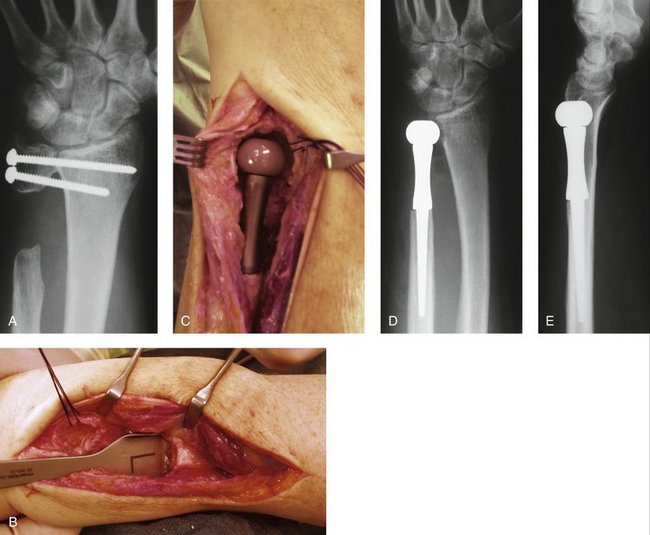

At the last follow-up examination, 16 of my 76 patients had a follow-up period of more than 5 years with a mean of 95 (61 to 124) months. All of these patients had suffered from painful instability after a resection arthroplasty of the DRUJ (Fig. 36-14A,B). Overall function of their hands had significantly improved after reconstruction of the DRUJ, and all patients would have had the operation again. Twelve patients returned to their original profession, and 4 patients retired due to their age. With the use of a visual analog scale (from 0 to 10), pain was found to be remarkably reduced from a mean of 8.7 preoperatively to 2.0 at the latest follow-up. Preoperative grip strength averaged 42% compared with the contralateral side and increased to a mean of 74%. Not only was forearm rotation found to be significantly improved after the procedure from a mean of 126 to 144 degrees, but overall wrist range of motion was found to have improved to a similar amount as well. Overall satisfaction with the outcome of the procedure was found to be very high, with a mean of 8.4 on a visual analog scale from 0 to 10.

FIGURE 36-14 A, Posteroanterior radiograph of a 36-year-old patient 11 years after a hemi-resection interposition arthroplasty and secondary shortening of the distal ulna. B, Transverse loading view of the same patient demonstrating the painful radioulnar impingement. C, Posteroanterior view 6 weeks after DRUJ reconstruction. D, Posteroanterior radiograph 7 months after ulnar head replacement showing bone resorption of the distal ulna under the neck of the prosthesis as well as initial remodeling of the sigmoid notch toward the head of the prosthesis. E, Posteroanterior radiograph 6.3 years after the procedure demonstrating the final remodeling of the sigmoid notch as well as the new bone formation filling the gap under the neck of the prosthesis.

Radiological Results

It is quite normal to find some early bone resorption at the distal end of the ulna under the collar of the prosthesis (see Fig. 36-14C, D). It averaged 2 mm and occurred in 6 of these 16 patients. In 4 patients the resorption area secondarily filled up with new bone over time (see Fig. 36-14E). Additionally, it is common to find some reactive bone remodeling at the sigmoid fossa, and I did notice this in 5 of the 16 patients. These bone reactions were harmless and were found to be completed in all patients after 12 to 18 months. Most importantly, there has been no sign of late loosening of the stem of the prosthesis but obvious osseous integration.

1. Van Schoonhoven J, Prommersberger KJ, Lanz U. The importance of the distal radioulnar joint for reconstructive procedures in the malunited distal radius fracture. Orthopäde.. 1999;28:864-871.

2. Buck-Gramcko D. On the priorities of publications of some operative procedures on the distal end of the ulna. J Hand Surg [Br].. 1990;15:416-420.

3. Schiltenwolf M, Martini AK, Bernd L, Lukoschek M. Ergebnisse nach Ellenköpfchenresektion. Z Orthop.. 1992;130:181-187.

4. Minami A, Ogino T, Minami M. Treatment of distal radioulnar disorders. J Hand Surg [Am].. 1987;12:189-196.

5. Bowers WH. Distal radioulnar joint arthroplasty: the hemiresection-interposition technique. J Hand Surg [Am].. 1985;10:169-178.

6. Lees VC, Scheker LR. The radiological demonstration of dynamic ulnar impingement. J Hand Surg [Br].. 1997;22:448-450.

7. Sauvé L, Kapandji M. Nouvelle technique de traitement chirurgical des luxationes récidivantes isolées de l’extrémité inférieure du cubitus. J Chir.. 1936;47:589-594.

8. Minami A, Suzuki K, Suenaga N, Ishikawa J. The Sauvé-Kapandji procedure for osteoarthritis of the distal radioulnar joint. J Hand Surg [Am].. 1995;20:602-608.

9. Carter PB, Stuart PR. The Sauvé-Kapandji procedure for post-traumatic disorders of the distal radio-ulnar joint. J Bone Joint Surg Br.. 2000;82:1013-1018.

10. Swanson AB. Implant arthroplasty for disabilities of the distal radioulnar joint: use of a silicone rubber capping implant following resection of the ulnar head. Orthop Clin North Am.. 1973;4:373-382.

11. Fatti JF, Palmer AK, Mosher JF. The long-term results of Swanson silicone rubber interpositional wrist arthroplasty. J Hand Surg [Am].. 1986;11:166-175.

12. White RE. Resection of the distal ulna with and without implant arthroplasty in rheumatoid arthritis. J Hand Surg [Am].. 1986;11:514-518.

13. McMurtry RY, Paley D, Marks P, Axelrod T. A critical analysis of Swanson ulnar head arthroplasty: rheumatoid versus nonrheumatoid. J Hand Surg [Am].. 1990;15:224-231.

14. Stanley D, Herbert TJ. The Swanson ulnar head prosthesis for post-traumatic disorders of the distal radioulnar joint. J Hand Surg [Br].. 1992;17:682-688.

15. Sagerman SD, Seiler JG, Fleming LL, Lockerman E. Silicone rubber distal ulnar replacement arthroplasty. J Hand Surg [Br].. 1992;17:689-693.

16. Petersen MS, Adams BD. Biomechanical evaluation of distal radioulnar reconstructions. J Hand Surg [Am].. 1993;18:328-334.

17. Bieber EJ, Linscheid RL, Dobyns JH, Beckenbaugh RD. Failed distal ulna resections. J Hand Surg [Am].. 1988;13:193-200.

18. Bowers WH. Instability of the distal radioulnar articulation. Hand Clin.. 1991;7:311-327.

19. Wolfe SW, Mih AD, Hotchkiss RN, et al. Wide excision of the distal ulna. J Hand Surg [Am].. 1998;23:222-228.

20. Watson HK, Gabuzda GM. Matched distal ulna resection for posttraumatic disorders of the distal radioulnar joint. J Hand Surg [Am].. 1992;17:724-730.

21. Van Schoonhoven J, Herbert TJ, Krimmer H. New concepts for distal radioulnar joint reconstruction using an ulnar head prosthesis. Handchir Mikrochir Plast Chir.. 1998;30:387-392.

22. Van Schoonhoven J, Fernandez DL, Bowers WH, Herbert TJ. Salvage of failed resection arthroplasties of the distal radioulnar joint using a new ulnar head prosthesis. J Hand Surg [Am].. 2000;25:438-446.

23. Fernandez DL, Joneschild ES, Abella DM. Treatment of failed Sauvé-Kapandji procedures with a spherical ulnar head prosthesis. Clin Orthop Relat Res.. 2006;445:100-107.

24. Van Schoonhoven J, Herbert T. The dorsal approach to the distal radioulnar joint. Tech Hand Up Extrem Surg.. 2004;8:11-15.