Tumours of the stomach and small intestine

Introduction

Tumours of small bowel are rare. Of the malignant tumours, lymphomas and gastrointestinal stromal tumours (GIST) are much more common than adenocarcinomas. Peutz–Jeghers syndrome is a rare inherited disorder characterised by multiple benign polyps in the small bowel and perioral pigmentation plus increased risk of breast, colorectal and other cancers. Patients are fairly commonly encountered at student examinations (see Ch. 27, p. 353).

Carcinoma of stomach

Pathology of gastric carcinoma

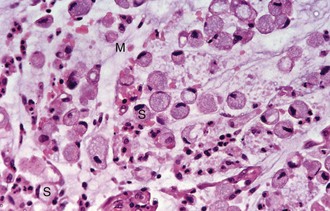

Gastric carcinomas are almost exclusively adenocarcinomas. Two distinct histopathological groups are recognised, each with its own epidemiological associations. The intestinal type has histological features similar to intestinal epithelium. Cells grow in clumps and there is marked inflammatory infiltrate. The second variety is the diffuse type. Here the cells are singular, often arranged in single file and surrounded by a marked stromal reaction. Tumour cells have large intracellular mucin droplets which displace the nucleus to the cell periphery, giving the characteristic signet ring appearance (Fig. 23.1). Intestinal-type carcinomas have a better prognosis than mucin-producing signet ring carcinomas.

Fig. 23.1 Signet-ring carcinoma of the stomach—histopathology

High-power view of typical infiltrating type of gastric carcinoma showing numerous signet ring cells S. This appearance is due to the presence of intracellular mucin M

• Fungating tumours—these polypoid lesions may grow to a huge size

• Malignant ulcers—these probably result from necrosis in broad-based solid tumours. Malignant ulcers are often larger than peptic ulcers (except for giant benign ulcers of the elderly) with a heaped-up indurated (hardened) margin

• Infiltrating carcinomas—this form spreads widely beneath the mucosa, and diffusely and extensively invades the muscle wall. This causes thickening and rigidity and the entire stomach contracts to a very small capacity. This is known as linitis plastica and its appearance likened to a ‘leather bottle’. Linitis plastica affects a slightly younger age group than intestinal-type cancer and has a very poor prognosis. Diagnosis may be delayed because endoscopic changes are often subtle and standard biopsies of mucosa may not show malignancy

‘Early gastric cancer’ is defined as cancer limited to the mucosa and submucosa. This is found most often as a result of endoscopic screening or whilst investigating possible peptic ulcer. Results of surgery in this group are excellent, with a surgical cure rate of about 90%.

Aetiology of gastric carcinoma and premalignant conditions

Helicobacter pylori infection

H. pylori is known to initiate peptic ulceration, and chronic H. pylori infection has become a prime suspect for initiating intestinal-type gastric cancer. The organism can colonise gastric mucosa over long periods and cause chronic gastritis which may progress to type B multifocal atrophic gastritis. In one biopsy study of gastric cancers, H. pylori was found in 90% of intestinal-type cancers, whilst only 30% of the diffuse type were infected. The carcinogenic mechanism of H. pylori may involve alterations to the gastric acid–pepsin environment, with increased cell turnover and possibly enhanced mucosal susceptibility to ingested carcinogens. H. pylori eradication does not reverse gastric atrophy but does improve the enzymic and hormonal secretory capacity of the stomach. H. pylori also appears likely to be involved in gastric lymphoma of the mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT) type (see p. 322).

Clinical features of gastric carcinoma

In advanced disease, up to half the patients are asymptomatic and the rest have pain, nausea, vomiting, anorexia or a feeling of fullness after small meals (early satiety). Sometimes these symptoms are there months before the patient presents. Anaemia from chronic occult blood loss is common and one-third have positive stool tests for occult blood. One-third have cachexia (severe weight loss and wasting). This usually indicates metastatic disease and may be the only manifestation of cancer at the time. Of the 70% who present with advanced local disease (stage T3), more than half have extensive abdominal nodal spread and half have distant metastases. The presenting features of gastric carcinoma are summarised in Box 23.1.

Direct spread and metastasis

• Direct spread into the transverse colon is not unusual in advanced cases and sometimes results in gastro-colic fistula formation, with true faecal vomiting

• Transperitoneal (or transcoelomic) spread may involve the surface of the ovaries (Krukenberg tumour) or form masses in the pouch of Douglas; a mass is often palpable on rectal examination

• Remote lymph node spread—the left supraclavicular (Virchow’s) lymph node classically becomes invaded via the thoracic duct, giving a palpable mass (Troisier’s sign) sometimes found at initial presentation

• Haematogenous spread to involve liver, lungs, brain and bone is common

Investigation of suspected gastric carcinoma

In areas with a high incidence of gastric cancer, endoscopic screening (Fig. 23.2) is an effective and popular method of detecting early disease. It is widely employed in Japan, with the result that over 40% of cancers operated upon after screening have been in a pre-symptomatic stage and can truly be defined histologically as ‘early gastric cancer’. About 90% of these patients undergo potentially curative operations.

Fig. 23.2 Endoscopic view of carcinoma of the stomach

Gastroscopic view of large fungating intestinal-type carcinoma of stomach in the prepyloric region C. Diagnosis was confirmed by endoscopic biopsy

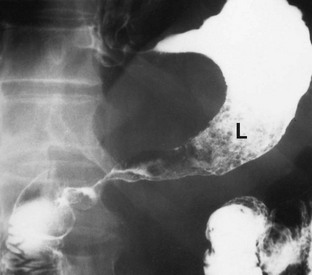

Barium meal used to be the standard investigation but it was difficult to differentiate between benign gastric ulcer and carcinoma. The radiological appearances of a typical gastric malignancy is shown in Figure 23.3 for historical reasons. Endoscopy, which allows visual inspection and biopsy, is now the standard investigation for suspected carcinoma of the stomach. The site of a lesion may be important as benign ulcers are usually found on the lesser curve or in the prepyloric area whereas carcinomas arise in any part of the stomach. The initial endoscopy in a patient found to have carcinoma gives an accurate diagnosis in 90% of those with exophytic lesions (where the tumour grows out into the lumen) but only 50% for infiltrating lesions. Multiple biopsies improve these rates, as do repeat endoscopy and re-biopsy of suspicious lesions.

Gastric polyps

Genuine adenomatous polyps are rare. These are true neoplasms, with histological and morphological forms similar to adenomatous polyps of the large intestine (see Ch. 27). Adenomas are usually single, large and asymptomatic. Most are found incidentally on endoscopic examination. Up to 40% show histological features of malignancy. Treatment is by endoscopic excision biopsy (submucosal resection).

Gastrointestinal stromal tumours (GIST)

Gastrointestinal stromal tumours are rare mesenchymal tumours that can arise anywhere in the GI tract. They were once thought to be leiomyomas because of the histological similarity but immunocytochemical markers can now distinguish mesenchymal tissue types and differentiate them from muscle and nerve tumours. GISTs have now been identified as originating from the interstitial cells of Cajal, the so-called ‘pace-makers’ of gut motility. GISTs are most frequently found in the stomach and can range from < 1 cm to > 20 cm. The risk of malignancy is determined partly by tumour location but mostly by size and histological mitotic index (see Table 23.1). Most gastric GISTs are small (< 5 cm) and have a low mitotic index.

Table 23.1

Risk of aggressive behaviour of gastrointestinal stromal tumours (GIST)

| Risk of aggressive behaviour (malignant potential) | Greatest dimension (cm) | Mitoses per 50 microscope high-power fields |

| Very low | < 2 | < 5 |

| Low | 2–5 | < 5 |

| Intermediate | < 5 | 6–10 |

| 5–10 | < 5 | |

| High | > 5 | > 5 |

| > 10 | Any number | |

| Any size | > 10 |

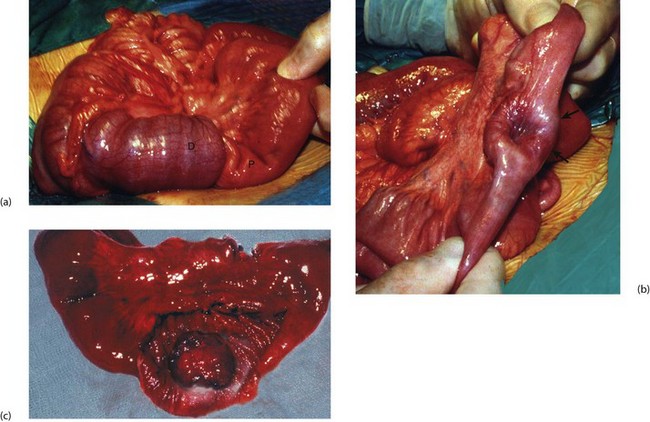

GISTs are often diagnosed incidentally at endoscopy. They can be sessile (domed) or pedunculated intramural lesions covered by normal mucosa (Fig. 23.4b). Small lesions may be asymptomatic; large lesions produce symptoms or signs of any abdominal mass. Gastric tumours are prone to haemorrhage via a central ‘umbilicated’ ulcer (Fig. 23.4a); these are typically found after an acute episode of haematemesis. Following diagnosis and before surgery, the patient may need to be staged by CT to confirm the size and exclude metastases (local, nodal or hepatic). Suitable biopsies allow immunocytochemical analysis, but it can be difficult to obtain sufficiently deep samples. Local resection is appropriate if the lesion has low malignant potential; malignant lesions require full oncological clearance as for other gastric cancers.

Small bowel gastrointestinal stromal tumours

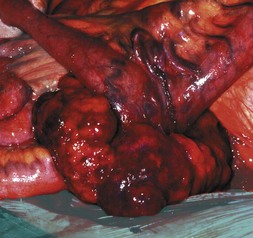

GISTs of small bowel are histologically similar to gastric tumours but may present by obstructing the lumen or growing out from the serosal surface of the bowel (Fig. 23.5). Primary resection and anastomosis is the usual treatment and survival is influenced by the size and mitotic counts.

Gastric and small bowel lymphomas

Pathology and clinical features of lymphomas

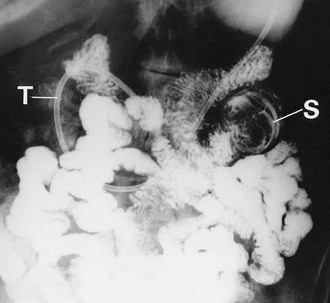

In the small intestine, lymphomas also produce bulky lesions which may obstruct, ulcerate, bleed or even perforate. Occasionally, a lymphoma provides the focus for an intussusception (see Figs 23.6 and 23.7 and also Fig. 50.12, p. 624). Small bowel lymphoma may be a complication of coeliac disease but the risk is only about six times higher than for the general population.